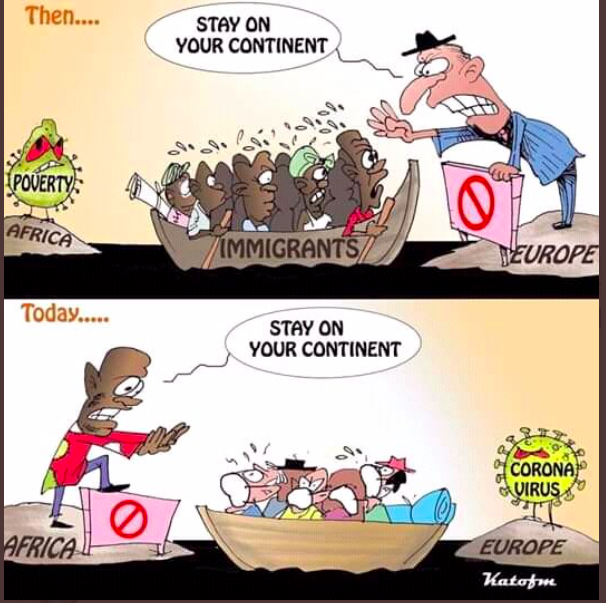

‘Stay on your continent!’

Coronavirus and the alarm of European spread in South Africa

When the first cases of infection started to appear in southern Germany, Jens Spahn, the Federal Minister of Health, was optimistic about the ability of German health authorities to contact trace and isolate infected persons (n-tv, 2020). Everyday life would continue while specialist tracer teams were hard at work. The borders would certainly remain open. Echoing other politicians in European countries with a ‘sober’ approach, countries considering more drastic measures to slow the spread, such as closing their borders and enforcing travel bans with Italy, were almost condescendingly considered as alarmist and anti-European Union (EU) (Welt, 2020; Reuters, 2020; Drbyos, 2020). It was better to accept that the coronavirus was inevitably going to infect 60 to 70 percent of the German population, with the overwhelming majority of infected persons only experiencing mild symptoms (BBC, 2020).

The goal was not to stop the virus, but to slow its spread to allow the health system to cope, with as little disruption to social and economic activities as possible. Contrary to these ‘optimistic’ assumptions, the infection rate in Germany rose sharply, as in other similarly sober-minded European countries. Community transmission was prevalent; tracing teams could not keep-up. In my apartment in Berlin-Spandau where I resided at the time, my housemates from Iran, Italy, Brazil, Zambia, Nigeria, Egypt and myself (South Africa), also started to feel uneasy. The middle-aged Italian plumber, having telephone contact with desperate family in lockdown Italy, tried to enforce strict rules through our Whatsapp group, rather than meeting face-to-face. For the Italian, apart from social distancing and hygiene measures, those who could, should leave the apartment to decrease the chance of infection for everybody. The risk of infection was high because nobody could really self-isolate in an overcrowded apartment. Understanding the seriousness of the situation, the Italian fellow resident was putting into place measures far more stringent than the German government recommended at the time. It was uncertain if the government would ever do so, despite the soaring infection rate. As others without much private space, I decided to leave Berlin for South Africa, my home country, before travel bans were imposed on the world’s new epicentre — Europe.

A popular Ugandan cartoon doing the rounds on South African social media. Copyright: Richard Kato.

I arrived in South Africa on 16 March on a virtually empty flight. There was a day to spare before South Africa’s travel ban came into effect and airlines would largely stop flying. By mid-March, South Africans were advocating for strict measures to halt the spread from Europe. There were calls to close all the borders and ban entry especially of ‘rich’ European tourists. Nervousness was being exacerbated not only by ‘super-spreader’ tourists who were asymptomatic while visiting wine farms and restaurants — who still found it more important to get a summer tan during a COVID-19 pandemic — but wealthier South Africans who were returning from travels in Europe for business and leisure. Initially a handful, almost all the recorded infections were wealthier South Africans returning from Europe (NICD, 2020). Anger was directed at such travellers for being naive about South Africa’s predicament: the healthcare system is weak, poor South Africans will not be able to self-isolate in crowded townships (as in some instances, in Berlin) and millions of people have compromised immune systems (Schneider, 2020). Usually secluded in suburbs, the domestic worker or gardener working at these households could spread the virus to marginalised communities (Staff Reporter, 2020). Unlike European and Asian countries, South Africa has millions of young and middle-aged adults living with HIV and tuberculosis. It is not entirely clear how those with HIV will react to COVID19, but talk about accepting the presence of COVID-19 as German and other Western European governments do (or did), where younger people are likely to survive an infection, is unfathomable for many in a country where millions could die from comorbidity. As China has largely achieved, South Africa has no option but to eradicate COVID-19.

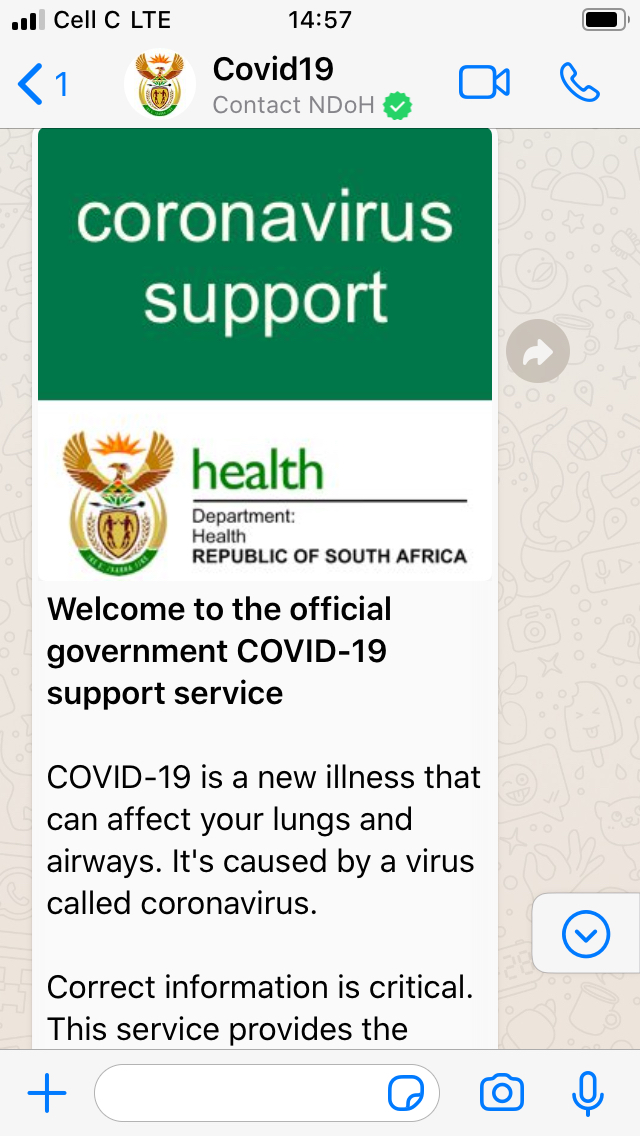

The South African Government Whatsapp group to stay informed about the most recent Coronavirus developments. Copyright: Brandaan Huigen.

Along with other African countries which have weak healthcare systems, while taking the advice of the World Health Organisation to use speed rather than delayed perfection in trying to fight COVID-19, South Africa imposed travel bans on certain European countries and nationals, to the relief of many South Africans expressing their views on Twitter. South African returnees, such as myself, have to self-quarantine for 14 days and check their temperatures regularly. Anyone can join a government Whatsapp group to stay informed about the recent developments. While a lockdown has not been put in place yet, because only a few cases of community transmission have been found, schools, universities and churches have been closed (although many mega-churches still want to congregate for Easter). Those who can, should work from home. There is especially concern about shebeens (taverns) with heavy alcohol consumption becoming hotbeds for transmission. Although, for now, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa is not as strict as Uganda’s President Yoweri Moseveni, who said that “Drunkards sit close to one another. They speak with saliva coming out of their mouth. They are a danger… All these [taverns and discos] are suspended for a month” (Polela, 2020). The nighttime ban of shebeens and restaurants selling alcohol will however be enforced. To prevent anger amongst shebeen owners and dependent customers, the government is recommending that shebeens start liquor delivery services to homes.

The capable private hospitals have been attending to moderate COVID-19 cases of returning travellers from Europe who are insured. These hospitals have also been responsible for contact tracing. If South Africa does come to a point of widespread community transmission, as has happened in Germany, these hospitals will have to share their capacity. Fortunately, the negotiations are going well between the state and the private healthcare sector. The hospitals of Netcare and Mediclinic, the two biggest private hospital groups, will be able to provide thousands of beds in the event that the public and military hospitals become overburdened with uninsured patients (Buthelezi, 2020). The health inequalities that follow economic disparities in South Africa can be somewhat dampened. There are also drastic plans to remove families who become infected from crowded townships and quarantine them in government accommodation, instead of allowing self-quarantine (SANews, 2020).

The Secretary General of the African National Congress speaking with a yellow face mask to the South African public about beating Coronavirus. Copyright: African National Congress Twitter.

The hope is that COVID-19 can be eradicated before it puts a large proportion of the population at risk who do not have the luxury of a strong immune system. Almost in reverse to many European leaders, who seem fearful of showing fear in public, South African leaders wear orange face-masks while attempting to scare the public over social media about COVID-19. It remains to be seen if these measures will work, but there is a sense that alarm is warranted. The commentariat argue that the ANC government has started to put measures in place on time (Haffajee, 2020), preventing an Italian situation. But from an initial strict stance, the discourse of acceptance is seeping into Zweli Mkhize, the Health Minister’s, communication to the nation: South Africans should realise that 60 to 70 percent of the population will get sick. Perhaps not so coincidentally, this utterance came after Germany sent funds for COVID-19 test kits to South Africa. During a TV interview about these funds, the German Ambassador, Martin Schäffer, hoped that South Africans would come to their senses: as a democracy, liberal values should take precedence over draconian measures to fight the virus (eNCA, 2020). Life must go on. Specifically, travel bans on Europeans and border closures were untoward, because COVID-19 does not know borders — a common expression used amongst liberal leaders.

As in other African countries where the likelihood of comorbidity for younger populations is extremely high, there is understandably confusion about the best strategy of how to fight COVID-19. Should it be the slow sober or swift draconian response, or a combination? Which of these is in reality possible? Both approaches, in their extremes, seem daunting for South Africans, but with the Chinese successes of late, many want hard and proactive measures catered to the social and cultural milieu of the country to save lives. This dilemma is an important opportunity for (Medical) Anthropologists to urgently reflect on, and advise on the way forward.

Brandaan Huigen is a Ph.D. candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the Freie Universität Berlin. He was awarded a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) doctoral fellowship to research the relationship between property crime and material culture in South Africa. A common thread throughout his research is an interest in the cultural dimensions of economic inequality.

Email: brandaanhuigen@gmail.com

Twitter: @b_huigen

ResearchGate: Brandaan Huigen

#Witnessing Corona

This article was simultaneously published on the Blog Medical Anthropology . Witnessing Corona is a joint blog series by the Blog Medical Anthropology / Medizinethnologie, Curare: Journal of Medical Anthropology, the Global South Studies Center Cologne, and boasblogs.

References:

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2020. Coronavirus: Up to 70% of Germany could become infected – Merkel. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-51835856. Last access: 11 March 2020.

Buthelezi, Londiwe. 2020. Coronvirus: How SA medical aids and hospital groups will pitch in. Fin24. https://www.fin24.com/Companies/Health/coronavirus-how-sa-medical-aids-and-hospital-groups-will-pitch-in-20200319 Last access: 19 March 2020.

Drbyos. 2020. Macron: “Closing the borders with Italy is a bad decision”. World Today News. https://www.world-today-news.com/macron-closing-the-borders-with-italy-is-a-bad-decision/. Last access: 10 March 2020.

eNCA. 2020. Germany make huge donation to help SA’s virus fight. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hztCK6hejtc. Last access: 13 March 2020.

Haffajee, Ferial. 2020. Ramaphosa shows mettle as he declares Covid-19 national disaster and the world’s gravest emergency. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-03-15-ramaphosa-shows-mettle-as-he-declares-covid-19-a-national-disaster-and-the-worlds-gravest-emergency/. Last access: 15 March 2020.

n-tv. 2020. Das sagt Gesundheitsminister Spahn zum Coronavirus. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba0UWDR1mv4. Last access: 28 January 2020.

Polela, McIntosh. 2020. https://twitter.com/toshpolela/status/1240594017110437890. Last access: 19 March 2020.

Reuters. 2020. Closing borders won’t stop coronavirus – German Health Minister. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-germany/closing-borders-wont-stop-coronavirus-german-health-minister-idUSKBN20Y0NQ. Last access: 11 March 2020.

SANews. 2020. Government identifies 37 quarantine sites countrywide. South African Government News Agency. https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/government-identifies-37-quarantine-sites-countrywide. Last access: 19 March 2020.

Staff Writer. 2020. Domestic workers and the coronavirus in South Africa – what you need to know. 2020. Business Tech. https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/382343/domestic-workers-and-the-coronavirus-in-south-africa-what-you-need-to-know/. Last access: 17 March 2020.

Schneider, Victoria. 2020. Tension, fear as South Africa steps up coronavirus fight. Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/tension-fear-south-africa-steps-coronavirus-fight-200318043032147.html. Last access: 18 March 2020.

The National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD). 2020. http://www.nicd.ac.za. Last access: 19 March 2020.

Welt. 2020. Coronavirus in Europa: Spahn gegen Reisebeschränkungen in der EU wegen Covid-19. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UPWTM1h-IIU. Last access: 6 March 2020.