Instagram as a Catalyst for Digital Gemeinschaft During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam

In early 2020, news articles documenting a possible coronavirus pandemic began appearing in countries worldwide, and while concerns were rife, few could have envisaged that so many of society’s taken-for-granted routines and norms would endure the disruption so visibly seen and felt in recent months. Across the world the recursive patterns of daily life suddenly gave way to dystopic realities, and stories about government-mandated lockdowns, overcrowding in intensive care units, and myriad economic and social challenges began dominating news headlines. While the distributors of this information clearly intended to provide updates on the developments surrounding the virus, any sensible person can detect another motive: the advocation for each person to adopt practices that support the best interests of the public. The arguments over the effectiveness of facemasks notwithstanding, numerous populations around the world have broadly coalesced in an attempt to quell this virus by staying home or social distancing if venturing into public spaces.

Social media, always a site for controversy, has repeatedly been criticized as a channel of disseminated misinformation (Depoux et al. 2020; Frenkel, Alba, & Zhong 2020) and recently identified as an outlet for public shaming (Bresciani and Hughes 2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the negative affordances permitted by social media, we ought to be mindful of the positive impact this media can yield, particularly to better harness its communication potential during crisis periods. Some scholars, for instance, have argued that COVID-19 offers the medical community an opportunity to utilize (with caution) social media platforms to communicate scientifically grounded medical knowledge between healthcare workers and the public (Eghtesadi & Florea 2020: p. 390). Others have observed how self-disclosures on social media, particularly as it relates to health information, seems to be communicated more willingly, as “there is a sense of public responsibility to share one’s COVID-19 diagnosis with the community – when available” (Nabity-Grover, Cheung, & Thatcher 2020: p. 3).

Social media micro-celebrities, or influencers, are also capable of productively contributing to this fight, whether through partnering with medical professionals to distribute information or promoting unity, camaraderie, and a communal spirit. For example, numerous Instagram micro-celebrities in the largest city and economic engine of Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City (hereby referred to as Saigon, still its common moniker), have posted encouraging messages, advocated for the adherence to safety measures, and created opportunities for rapport and support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first reported case of COVID-19 in Vietnam was identified on 23 January 2020 (Coleman 2020). Within days, all flights to and from Wuhan, China, the virus’ first epicenter, were cancelled. By February, all face to face educational activities, including those at universities, were suspended across the country and social distancing measures were implemented, as well as the mandatory wearing of masks in public places. The cancellation of all international flights soon followed, and in April the country instituted a nationwide isolation campaign to last for two weeks (it was eventually extended for another week), wherein all non-essential services were shuttered. Despite the devastating economic results generated by the imposed lockdowns, the Vietnamese population overwhelmingly agreed with the measures (Truong 2020). After a few short weeks, the measure seemed to be successful, as between 22 April and 24 July, no new community transmissions were recorded. As of this writing (29 Sept 2020), there have been 1,077 total cases and 35 COVID-19 attributed deaths in Vietnam (Vietnamese Ministry of Health 2020). Vietnam has thus far been widely praised for their response to the coronavirus outbreak (Zhang & Sy 2020). The country’s efforts receiving acclaim have ranged from a virial hand washing sensation, which appeared on the popular HBO program Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, to its collection of solidarity-inspiring posters, several of which were featured in The Guardian (Humphrey 2020).

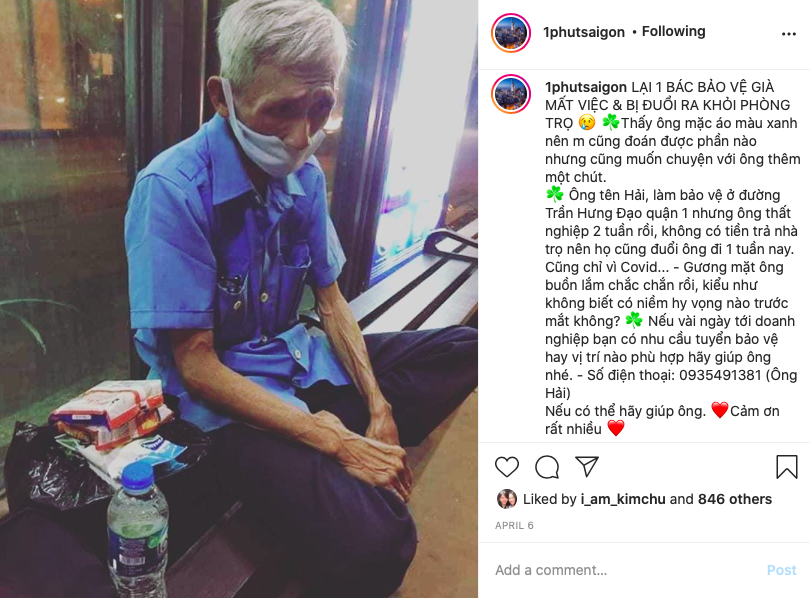

This photo, uploaded by @1phutSaigon, tells the story of a man who lost his job and residence due to the economic impact of Saigon’s COVID-19 lockdown. Through Instagram, the owner of the account shared the man’s story with the hope of finding him new employment. Source: Original Instagram Post. Usage authorized by the author.

For this blog post, my interest concerns popular Vietnamese-based micro-celebrities on Instagram and identifying any role they may have played in contributing to what the Vietnamese government has coined as “chống dịch như chống giặc” (fight the virus like you’d fight in war). Although the photo-based social media application is not nearly as popular in Vietnam as Facebook, YouTube, or the country’s homegrown social network, Zalo, Instagram is still utilized by 46% of the country’s internet users aged 16-64 (Hootsuite & We are Social 2020). Through a textual reading of images and their accompanying captions from select accounts featured on the Instagram platform, this piece proposes that a variety of micro-celebrities in Vietnam have played a critical role in sharing civic value (Shirky 2010), thus creating the sort of solidarity that constitutes a collective we (Spinosa, Flores, and Dreyfus 1997: p. 116) and therefore contributing to what Rich Ling (2012) refers to as digital Gemeinschaft, a digitally-connected community characterized by fellowship.

Social Media and Social Cohesion

Over the previous several decades, conversations about the impact of mobile social media on social cohesion have become ubiquitous. Rich Ling, one of the most prominent contributors of these discourses, argues against notions suggesting that these “technologies of mediation” (Ling 2012) have adversely impacted social cohesion. Instead of enabling individualist tendencies and being “alone together” (Turkle 2011), Ling proposes that these technologies are, in fact, repurposed by users to facilitate a digital Gemeinschaft. While his output largely focuses on areas wherein stronger ties are likely prevalent, such as between family members and romantic partners (see Ling 2008), it behooves us to consider digital Gemeinschaft as equally fosterable amongst those who have never met in the physical co-present. This is especially true for younger generations, whose adoption and negotiated use of mobile social media, and

Instagram specifically, has coincided with the visible prominence of micro-celebrities, a term used to describe ordinary social media users who have increased their popularity through a combination of complementary electronic media (Senft 2008). For younger generations worldwide, micro-celebrities are perceived as credible and relatable, especially when compared to traditional celebrities like actors, musicians, and models (Southgate 2017); “this is elucidated by their ability to create communities where users feel more connected to the [micro-celebrity] through higher levels of engagement, authenticity, and relatability” (Nouri 2018, p. 3). The formation of a parasocial relationship (Horton & Wohl 1956) between micro-celebrities and users occurs, in part, due to the micro-celebrity occupying a position in the user’s personalized feed alongside family members and other close companions (Khamis, Ang, & Welling 2017). Through a simulacrum of give and take, a feeling of intimacy at a distance materializes for the user, and gradually the perceptual distinctions between the micro-celebrity, family members, and friends begin to blur. In Saigon, it appears that a range of Instagram micro-celebrities were not only aware of the strength of these parasocial relationships, but also realized that they could be pragmatically used to promote communal solidarity during the city’s COVID-19 pandemic.

Creating Civic Value Through Instagram Practices During COVID-19

An account holder named @odaucungchup (94.6k followers) regularly uses the platform to depict stories occurring around the city. During the pandemic, however, he adjusted this content to specifically highlight and raise awareness for the most vulnerable members of society: those whose livelihood would be severely impacted by what was, in effect, a three-week lockdown. In one post, uploaded on 1 April 2020, the first day of the lockdown, @odaucungchup shared information about local restaurants providing food free of charge (or significantly discounted) for those in desperate need. The user also promoted the efforts of a company named @may.totebags (66k followers), who altruistically donated tailored masks to people frequently in close proximity with others (such as bus drivers and passengers). In addition to @odaucungchup, a crowd-sourced account named @1phutSaigon (in English: 1 Minute Saigon; 27.5k followers), also focused on raising awareness for struggling citizens. In particular, one post, featured below, told the story of a man who recently lost his position as a security guard and was evicted from his temporary residence. The administrator of this account, however, went beyond simply sharing this heartbreaking story; he also provided the man’s name and contact information in an attempt to help him find employment.

Other account holders exhibited how the cityscape had drastically changed during the imposed lockdown. @cuongkentnk (7.5k followers), aptly describable as an urban explorer (see Nestor 2012), typically uses Instagram to visually depict the vast Saigonese cityscape and its outskirts. During the pandemic, he regularly posted images of the abandoned city streets, showcasing an urban environment completely void of people. He also utilized the popular hashtag #stayhome and/or #stayhomeforus, seemingly to promote the government’s decree to self-isolate. Following the city’s formal enforcement of social distancing procedures, @cuongkentnk began an official Coronavirus photo series, posting a new image each day to endorse the policy. The images were sometimes amended to include popular visuals, such as the government-sanctioned art celebrating the efforts of the country’s medical workers.

In addition to urban photographers, prominent food bloggers likewise seemed ready to encourage communal solidarity. @ansapsaigon (173k followers), for instance, frequently suggested to his followers to eat at home with the intent of keeping people off the streets or hosted cooking programs to teach people how to prepare their own meals (Hoa Hoc Tro, 2020). He also included the popular phrase “ăn ở nhà cũng ngon” (eating at home is also delicious) as a hashtag. Another food blogger frequently using the hashtag, @tebefood (120k followers), incorporated more mukbang-oriented content on her feed. Mukbang, while initially popularized in Korea in 2010 on AfreecaTV has since become a global phenomenon (Hawthorne, 2019). Mukbang, a portmanteau of the Korean words “muk-ja” (let’s eat) and “bang-song” (broadcast), is, as the name suggests, “a broadcast where people eat” (Choe, 2020: p. 173). Among the main reasons to engage in a mukbang session is to establish a sense of social companionship (Donnar 2017), which is critical to help overcome loneliness and feelings of isolation, especially during dinner, a mealtime typically associated with strengthening kinship bonds, engaging socially, and relaxing after the workday. Furthermore, mukbang enables people to connect and interact not only with the tele-present person consuming the food, but also with those participating in the show’s corresponding chat box. This chat box is especially important for nourishing the feeling of belonging, as performers often call out attendees by name and respond to their questions and comments (Bruno & Chung 2017). Given that numerous people were isolated in their homes during the coronavirus lockdowns, both domestically and abroad, and in some cases separated from family members and other social supports, it is highly likely that live mukbang productions provided an alternative to eating alone whilst simultaneously cultivating a sense of belonging and camaraderie. Following the lifting of the lockdown measures, @tebefood organized and facilitated a food delivery evening, in which she used accepted donations from her followers to purchase food and subsequently deliver it to the city’s most impoverished residents. In the same post, she claimed that she will continue these crowd-sourced events into the autumn season.

While social media has been a site of widespread subversion during COVID-19, particularly to challenge governments and their health and safety directives (Limaye, et al. 2020), it has not been so in Saigon. Given the passing of a 2019 cybersecurity law, a piece of legislation that permits the restriction of online speech, it is possible to presume that these micro-celebrities are uncritically following (and promoting) the government’s coronavirus edict, especially since, as detailed in the 2020 Freedom House Report on the country, journalists, bloggers, and online human rights activists have been subjected to arrests and criminal convictions. I would like to caution against such positions, however, as the focus for these micro-celebrities seems situated on encouraging each follower to consider the immediate needs of the wider collective. As demonstrated by the World Values Survey conducted by the World Bank, “it is the ‘family-village-country’ values concerned with unity, cooperation, solidarity, harmony, and tolerance that shape the collectivism which is the core of Vietnam” (Nguyen 2016: p. 35). Although humanist western values are more prevalent in Vietnam as the country has integrated into the global economy, a steadfast commitment to community remains (Hofstede Insights 2020). In fact, the integration of western culture has “helped to promote personal awareness as it considered individuals of value … the development of the individual is not in opposition to but in support for the development of society” (Nguyen 2016: p. 37).

The responses to the COVID-19 pandemic by micro-celebrities like those referenced above are exemplars of Clay Shirky’s position that contemporary mobile and social media technologies have reignited a belief that each person can act and make a discernible difference in society, particularly to generate civic value (Shirky 2010). In Cognitive Surplus (2010), Shirky suggests that contemporary media users generate personal value by being active rather than passive and creative rather than consumptive. Furthermore, he argues that social media users are significantly motivated by social concerns, and increasingly consider their basic needs, like emotional satisfaction, linked to the achievement of a public goal through the creation and sharing of civic value; in the author’s own words, “the more we want to do so at the civic end of the scale, the more we have to bind ourselves to one another to achieve (and celebrate) shared goals” (Shirky 2010: p. 176). One of the positive affordances of digital technologies, especially in this context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Vietnam, is how they were be applied to improve the lives of people beyond the group: those who do not actively participate. The unemployed man referenced by @1phutSaigon, for instance, is likely not a social media user, if the abovementioned demographic data is to be believed, and is therefore not a direct participant. Yet, the interaction taking place between the micro-celebrity and his followers ignites an opportunity from which that man can certainly benefit.

Although this blog piece has only enough space to mention a few account holders, numerous others likewise displayed a zeal to preserve the city and its perceived essence by, in an ad hoc manner, leveraging their influencer status and rapport with followers to promote social solidarity, thus becoming an essential part of the city’s health governance. Moreover, by fervently endorsing the social need to self-isolate, by reaching out to those seeking companionship, and by raising awareness of vulnerable populations, each of these micro-celebrities showcased not only an affective connection to others in their community, but also a personal and moral obligation to act in the community’s interest, all of which are necessary for digital Gemeinschaft to thrive. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Saigon, these micro-celebrities seem compelled to assume responsibility and play a role in protecting the community, as if their identity as a citizen of the city depended on it.

Disclosing and Preserving Saigon

To close this blog post, I would like to intertwine the aforementioned observations with a theme that emerged from “The Instagrammable Saigon,” my in-progress ethnographic research project exploring the myriad depictions of Saigon on the Instagram platform. Following a series of semi-structured interviews with several Saigon-based Instagram account holders, I have found myself inspired to consider the platform’s uses as driven less by blatant instrumental rationality, particularly as it concerns the presentation of self (Ross, 2019), and instead as a place-making practice (see Malpas, 2006). Although each individual interviewee recruited for this project articulated their use of the platform through the context of their artistic style and inspiration, a thematic consensus eventually surfaced: the desire to showcase the city from unique experiential perspectives. Regardless of whether focused on urban exploration, the disenfranchisement of citizens, or the city’s vibrant culinary culture, each photographer aimed to use the Instagram platform as the means to disclose their intimately held understanding of Saigon. For each, Saigon is an enriching place worth unveiling to others, and while each post is an exploration and celebration of the city’s multifaceted nuances and diverse stories, each is also a form of preservation, of Augenblick (Grant 2015: 213-229).

The Instagram platform can certainly be understood as an archive of images and experiences, but to fully comprehend its importance in this context, we should likewise consider it as a visible manifestation of the photographers’ attunement with what they found meaningful about the city in a particular moment. Collectively, these experiential perspectives, told through visual imagery, can reveal the city’s rapidly changing urbanscape in new and fascinating ways, yet also reveal a community united by their enthusiasm and passion for this unique city, as well as an urge to preserve its recognized essence. Beyond the coronavirus pandemic, the contributions and connections to the community fostered by these micro-celebrities continues to develop, as each focus on topical themes and presents them in their own unique way, such as through a distinct photographic style, the contextualization of visuals, and a considerate reflection of their practice and its implications for the wider community. As a parting thought, I would therefore like to include a quote by Spinosa, Flores, and Dreyfus, as their words astutely encapsulate the collective response by these micro-celebrities to the coronavirus in Saigon:

“We feel solidarity with our fellow citizens when we recognize that we have already been engaged in preserving and perpetuating certain concerns. That is, we recognize that when we act according to practices that produce our culture with its particular identity and produce ourselves as citizens with identities appropriate to our culture, we are all engaged in the activity together. The together here means that we do this as a we” (Spinosa, Flores, & Dreyfus, 1997, p. 134).

As this piece has aimed to showcase, these micro-celebrities on Instagram, as Saigonese inhabitants, have intertwined a range of digital skills and efforts to promote togetherness and commitment to a common cause: conduct yourself in a manner which is necessary to protect each other and defeat this virus. Their practices are demonstrative of how social media platforms can be used to engage as a collective we and contribute to the fostering of social solidarity, thus demonstrating a thriving digital Gemeinschaft.

Written 24 September, revised 29 September 2020

Justin Michael Battin, Ph.D. is Lecturer of Communication at the School of Communication & Design at RMIT University in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. His current research focuses on the intersection of interactive media use and the phenomenological experience of place. He can be reached at: Justin.Battin[at]rmit.edu.vn

#Witnessing Corona

This article was simultaneously published on the Blog Medical Anthropology. Witnessing Corona is a joint blog series by the Blog Medical Anthropology, Curare: Journal of Medical Anthropology, the Global South Studies Center Cologne, and boasblogs.

References

Bresciani, Chiara & Geoffrey Hughes. 2020. “Virological Witch Hunts: Coronavirus and Social Control under Quarantine in Bergamo, Italy. https://boasblogs.org/witnessingcorona/virological-witch-hunts/. Last access: 10/09/2020.

Bruno, Antonetta & Somin Chung. 2017. “Mŏkpang: Pay me and I’ll show you how much I can eat for your pleasure.” In: Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema 9 (2), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17564905.2017.1368150

Choe, Hanwool. 2020 “Eating Together Multimodally: Collaborative Eating in Mukbang, a Korean livestream of eating.” In: Language and Society 48 (2), 171-208. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404518001355

Coleman, Justine. 2020. “Vietnam reports first coronavirus cases.” https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/public-global-health/479542-vietnam-reports-first-coronavirus-cases. Last access: 09/08/2020.

Donnar, Glen. 2017. “‘Food porn’ or intimate sociality: Committed celebrity and cultural performances of overeating in meokbang.” In: Celebrity Studies 8 (1), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1272857

Depoux, Anneliese, Martin, Sam, Karafillakis, Emilie, Preet, Raman, Wilder-Smith, Annelies, and Heidi Larson. 2020. “The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak.” In: Journal of Travel Medicine 27 (3), https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa031

Eghtesadi, Marzieh & Adrian Florea. 2020. “Facebook, Instagram, Reddit and TikTok: a proposal for health authorities to integrate popular social media platforms in contingency planning amid a global pandemic outbreak.” In: Canadian Journal of Public Health 111, 389–391. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00343-0

Freedom House. 2020. “Freedom in the World 2020: Vietnam.” https://freedomhouse.org/country/vietnam/freedom-world/2020. Last access: 22/09/2020.

Frenkel, Sheera, Alba, Davey, & Raymond Zhong. 2020. “Surge of virus misinformation stumps Facebook and Twitter.” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/08/technology/coronavirus-misinformation-social-media.html. Last access: 22/08/2020.

Grant, Stuart. 2015. “Heidegger’s Augenblick as the Moment of Performance.” In Grant, Stuart, McNeilly, Jodie, & Maeva Veerapen (eds.). Performance and Temporalisation: Time Happens. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. 213-229. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137410276

Hawthorne, Ellis. 2019. “Mukbang: Could the obsession with watching people eat be a money spinner for brands?” https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/marketing/mukbang-could-the-obsession-with-watching-people-eat-be-a-money-spinner-for-brands/596698.article. Last access: 10/08/2020.

Hoa Hoc Tro (2020) Food Travel Blogger. Online, accessed 09/08/2020. Available from: https://hoahoctro.tienphong.vn/hht-doi-song/hoi-food-blogger-va-travel-blogger-song-sot-qua-mua-dich-the-nao-1637916.tpo

Hootsuite & We Are Social. 2020. “Digital 2020 Global Digital Overview.” https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-vietnam. Last access: 08/09/2020.

Hofstede Insights. 2020. “Country Comparison: Vietnam.” https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/vietnam/ Last access: 29/09/2020.

Horton, Donald & Richard Wohl. 1956. “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction.” In Psychiatry 19 (3). 215-229, https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Humphrey, Chris. 2020. “In a war, we draw: Vietnam’s artists join fight against COVID-19.” https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/09/in-a-war-we-draw-vietnams-artists-join-fight-against-covid-19. Last access: 09/08/2020

Khamis, Susie, Ang, Lawrence & Raymond Welling 2017. “Selfbranding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers.” In: Celebrity Studies 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

Limaye, Rupali Jayant, Sauer, Molly, Ali, Joseph, Bernstein, Justin, Wahl, Brian, Barnhill, Anne, & Alain Labrique. 2020. “Building Trust While Influencing Online COVID-19 Content in the Social Media World.” In: The Lancet Digital Health 2 (6). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30084-4

Ling, Rich. 2008. New Tech, New Ties: How Mobile Communication is Reshaping Social Cohesion. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/new-tech-new-ties

Ling, Rich. 2012. Taken-for-Grantedness: The Embedding of Mobile Communication into Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/taken-grantedness

Malpas, Jeff. 2006. Heidegger’s Topology: Being, Place, World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/heideggers-topology

Ministry of Health. 2020. TRANG TIN VỀ DỊCH BỆNH VIÊM ĐƯỜNG HÔ HẤP CẤP COVID-19. https://ncov.moh.gov.vn. Last access: 27/08/2020.

Nabity-Grover, Teagen, Cheung, Christy, & Jason Bennett Thatcher. 2020. “Inside out and outside in: How the COVID-19 pandemic affects self-disclosure on social media.” In: International Journal of Information Management. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102188

Nestor, Jeff. 2012. “The Art of Urban Exploration.” https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/The-Art-of-Urban-Exploration-2546675.php Last access: 09/10/2020.

Nguyen, Quynh Thi Nhu. 2016. “The Vietnamese Value System: A Blend of Oriental, Western, and Socialist Values.” In International Education Studies 9 (12). 32-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n12p32

Nouri, Melody, “The Power of Influence: Traditional Celebrity vs Social Media Influencer.” In Pop Culture Intersections 32. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/engl_176/32

Ross, Scott. 2019. “Being Real on Fake Instagram: Likes, Images, and Media Ideologies of Value.” In: Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 29 (3), 359-374. https://doi.org/10.1111/jola.12224

Senft, Theresa. 2013. “Microcelebrity and the Branded Self.” In: Hartley, John, Burgess, Jean & & Axel Bruns (eds.). A Companion to New Media Dynamics. Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 346-354. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118321607.ch22

Shirky, Clay. 2010. Connectivity and Generosity in a Connected Age. New York, NY: Penguin Press. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/305328/cognitive-surplus-by-clay-shirky/

Southgate, Duncan. 2017. “The emergence of generation Z and its impact in advertising: Long-term implications for media planning and creative development.” In: Journal of Advertising Research 57 (2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2017-028

Spinosa, Charles, Flores, Fernando, & Hubert L. Dreyfus. 1997. Disclosing New Worlds: Entrepreneurship, Democratic Action, and the Cultivation of Solidarity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/disclosing-new-worlds

Truong, Mai. 2020. “Vietnam’s Communist Party Finds a Silver Lining in COVID-19.” https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/vietnams-communist-party-finds-a-silver-lining-in-covid-19/. Last access: 20/08/2020.

Turkle, Sherry. 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less From Each Other. New York, NY: Basic Books. https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/sherry-turkle/alone-together/9780465093656/

Vietnamese Ministry of Health 2020. TRANG TIN VỀ DỊCH BỆNH VIÊM ĐƯỜNG HÔ HẤP CẤP COVID-19. ncov.moh.gov.vn. Last access: 08/09/2020.

Zhang, Nan & Amandu Sy. 2020. “How did Vietnam do it? Public Health and Fiscal Measures Beat Back COVID-19.” https://www.uncdf.org/article/5598/how-did-vietnam-do-it-public-health-and-fiscal-measures-beat-back-covid-19. Last access: 08/09/2020.