Government, Church, and the Community of Believers

Managing the Coronavirus in Ethiopia during Easter Time

When the coronavirus enters Ethiopia

The first time I heard somebody talking about the coronavirus in Ethiopia was in my car, in Addis Ababa, at the beginning of February 2020, as I was giving a lift to some of my Ethiopian colleagues from one side of the city to the other. Chatting during the journey, one of them told her mates that she had heard about a deadly disease on the radio, which was spreading in China, and asked me if I knew its name. I just answered that the Italian newspapers referred to it as “coronavirus”, but, since “corona” is an Italian word, I didn’t know how to translate it to English or Amharic (the language we were using).

It took a short time to discover that the expression “coronavirus” would spread far more quickly than expected on people’s tongues and in mass media. At the time, I was surprised about the information that our colleague shared, since international news were not a usual topic of discussion among us. Most of my colleagues are middle-aged women with only a few years of formal education who came to the capital city of Ethiopia through rural-to-urban migration. They all work for a Catholic organization, in a project that offers different services to people in conditions of need, especially disabled and HIV-positive children without families – the same project I am involved in.

Conversations about the coronavirus became more frequent day by day up to 13 March, when they completely rocketed because of the finding of the first COVID-19-positive person in Ethiopia. On the streets of Addis Ababa, it became more and more common to see people wearing masks and gloves, as suggested by the government. The small shops, which used to serve clients from a wide window on their facade, marked the position where customers should stand to avoid close face-to-face contact with the trader. Banks, supermarkets and pharmacies placed small water tanks and soap-dispensers at their main doors to allow people to wash their hands properly before getting in. Advertisements explaining basic precautions started to appear on information placards and were broadcast on television and the radio. When making phone calls, special COVID-19 prevention messages were introduced to replace the usual ringing tone.

A placard on the pillar of the rapid transit system in the town centre shows some measures to prevent infections. 14 May 2020. Copyright: Alice Colombo.

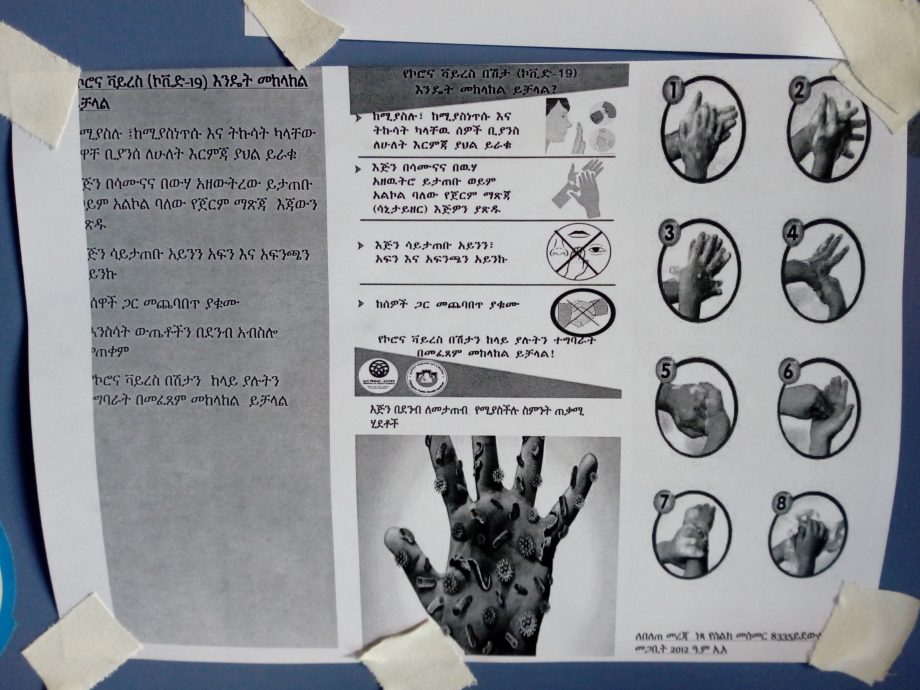

A paper hung on the door of a health office explains how to wash hands properly. 30 April 2020. Copyright: Alice Colombo.

As soon as the first case was reported, the government introduced preventive measures: within a few days, schools, sport events and large gatherings were announced to be suspended for two weeks (Fana BC 2020a). As the announcement did not specify what the word “large” really meant, most of the gatherings common to everyday life continued to be held. Churches did not close their doors either despite the fact that big numbers of believers kept gathering in their churchyards every day in order to attend daily functions or perform personal prayers. From this moment on, the community of believers was getting involved in an unspoken conflict between the government and the Church (namely, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church) which surfaced concerning the issue of how to manage the COVID-19 situation.

On 8 April, the Prime Minister declared a State of Emergency for the next five months[1] and a document with new specific indications was issued. The third part of the document, entitled “forbidden actions”, included, among others, a provision limiting gatherings to no more than four people (Office of The Prime Minister 2020: 2). The paragraph listing in detail all the prohibited types of gatherings mentions primarily those of religious nature.

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church’s authority among the population

In the words of Siena De Ménonville (2018: 106): “The history and place of Christianity in Ethiopian society are undeniably relevant, but they are also vast, intricate, and enigmatic. […] Inquiring into the issue of how situations of religious faith affect people’s identification, social networks, and community relations remains challenging and often impenetrable.” However, the fact that no greeting, no thanksgiving, no polite refusal – not even a sneeze – is produced without entrusting the interlocutor to God may be a good example of the relevance of the divine in everyday life. Similarly, typical Ethiopian social networks (like idir or mahaber) emerge in order to accomplish religious ceremonies such as funeral or saints’ celebrations. Most of the time, these informal associations become more than mere committees organizing feasts, since they allow their members to strengthen their relationships of mutual solidarity, which may turn useful in situations of difficulty.

The Ethiopian religious landscape is quite rich; the country hosts believers of different cults, above all Muslims and Christians. Christianity in Ethiopia takes different shapes, as Catholic Christians and Protestant Christians (in all their nuances) live together with the wide number of Orthodox Christians (43,5 percent of the population) (Index Mundi 2020). The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) is one of the five Oriental Orthodox Churcheswhich follow the monophysite doctrine, assuming that the nature of Christ is purely divine. The Ethiopian Church puts a strong focus on orthopraxy, the belief that correct conduct, both ethical and liturgical, is the best demonstration of one’s faith. One of the most important manifestations of orthopraxy is veneration of the icons of the saints placed inside the churches: “In front of icons, the Oriental Orthodox faithful light candles; they touch and kiss the icons; they pray in front of the icons, standing or kneeling. They even prostrate themselves in front of icons” (Chaillot 2016: 108). Because icons are thought to work as intermediaries between God and the believers, attending church to perform personal or collective prayer in front of them is central to the religious life of the faithful.

Even though nowadays Ethiopian Orthodox Christians make up less than half of the population of Ethiopia, a strong relationship between state and church has existed since the 4th century: “Since its foundation, the leadership of the Ethiopian Church was divided between two figures: the Egyptian Metropolitan bishop (or Abun) and a priestking, the ˈKing of Kingsˈ” (Ancel & Ficquet 2015: 65). This situation led to the constitution of a society highly intertwined with Christian identity. As a result, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has been considered as “the upholder of Ethiopian culture and the dominant framework through which Ethiopia could be understood” (De Ménonville 2018: 111). Indeed, according to the legend bequeathed by the book of Kebra Negest, the Ethiopian dynasty that led the country up to the reign of Haile Selassie descended from the line of King Solomon and of the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba through their son Minilik. During the centuries, this alleged link between the king of Israel and an Ethiopian queen strengthened the belief that a special bound existed between God and the Ethiopian people. Although the legend has been branded as a case of invention of tradition (Grierson 1993), for centuries, it endorsed the legitimacy of kings’ authority. For this reason, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church had a front-row role on the political scene up to the fall of the monarchy in 1975. Even during the dictatorship that followed, when all religious beliefs were strongly repressed, the Church managed to use its moral authority to condition the population, a reminder to the government of its retained power, proving that it was still holding its own (Pili 2009).

A view of the Church of Saint Mikael, in the area of Bole, Addis Ababa. 6 May 2020. Copyright: Stefano Spisni, published with permission.

The repartee about COVID-19 during Easter period

One month before the State of Emergency was declared – i.e. when the first COVID-19 preventive measures were enforced – the Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Abune Mathias, invited the population to respect the regulations of the Ministry of Health (tweet by @Ethiopialiveupd, 16 March 2020). However, most of the churches continued to host believers despite the government’s prohibition of “large gatherings”. During a phone conversation with the broadcast organization Voice of America, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church’s media director claimed that the situation was due to a lack of understanding, even more so as people were being exposed to wrong information, especially to the misconceptions instilled by social media. He also pointed out that these wrong behaviors must not be interpreted as a form of resistance to the regulations (Marks 2020).

The official position of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church became firmer during the first days of April, when the Holy Synod announced on EOTC TV that the followers of the Church must pray from home and only a limited number of priests should conduct prayers inside churches (Borkena 2020). If the words of the Patriarch had appeared ambiguous up to that moment – so much so that no church had fully complied with the ban on gatherings – from then on, the gates of the churches were shut. However, even this stronger provision failed to stop believers from gathering outside the gates where they kept performing their religious duties.

A tweet by @addisstandard summarizing the announcement broadcast by the Holy Synod. . Last access: 26/05/2020.

According to one of my interlocutors, the ways the Church enforced (or did not enforce) the governmental decrees could be linked with the everlasting conflict between the State and the Church:

„If the Church was really committed to encourage the believers to respect the laws, it could adopt additional measures so that people would not be confused about what they can and cannot do. For example, the gates of the churches have been closed in order to avoid gatherings, but since the Mass is broadcast over the churches’ loudspeakers, believers meet up out of the gates to attend the celebration.” (personal communication, 23 April 2020)

All these limitations emerged during a period of the year that is central to the life of believers, namely Lent time. The Abiy Tsom, the Great Lent Fast, lasts 55 days – this year from 24 February to 19 April – and consists of a time of purification, both physical and spiritual. In brief, it involves abstention from some foods (meat, eggs, milk and their derivatives) and a complete fasting up to 3 p.m. (except on Saturdays and Sundays). Meanwhile, believers are supposed to intensify private prayer and to attend functions in the churches.

Despite the restrictions imposed by the government and endorsed by the Holy Synod, many people carried on attending church. Especially on the days devoted to the most important saints, believers kept coming to the churches consecrated to them to pray in front of the closed gates, bowing down to the ground and kissing their fences – I even saw a man climbing one of the trees next to a church and crossing himself at its top. The police, if present, would only intervene to avoid the situation from getting out of control, rather than disperse the gatherings.

On 15 April, the Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church addressed a letter to the Prime Minister to request a loosening of the ban on gatherings for the days of Maundy Thursday (16 April 2020) and Easter (19 April 2020). In his words, denying believers the possibility of properly celebrating these moments would create great anger and lead to unnecessary conflicts (Fasil 2020). Up to that moment, the Patriarch had explicitly supported the preventive measures embraced by the government: first, by asking the community of believers to respect the dispositions, then, by declaring the closure of churches and encouraging private prayer. This had raised discontent among the Christian population, who found their own way to attend churches, as we have seen, by gathering outside the gates.

On Easter Eve, the Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed delivered a message to the faithful, reminding them that, as the resurrection of Christ taught us that joy follows pain and darkness, so it will be for us in this hard time of the pandemic (Fana BC 2020b). However, no official answer to the Patriarch was reported by the media.

During the week preceding Easter, the town of Addis Ababa became crowded again, though not as much as was usual at this time of the year. People did their best to make sure that despite being confined to their homes, they would be able to celebrate the feast decently, i.e. to break the fast on Easter day by eating meat – sheep or chicken – with family and neighbors. However, discourses about the celebration were permeated by a sense of despondency, longing for the days when waiting for Easter meant preparing for overwhelming joy, so hard to feel, instead, in these times of global distress (personal communication).

The gate of the Church of Saint Mikael in the neighborhood of Jemo is shut and a placard informs about the ban on shaking hands and the requirement of social distancing. 15 May 2020. Copyright: Stefano Spisni, published with permission.

Behind the moves of government and Church

The triangular relationship between the government, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the community of believers represents a crucial factor in the management of the coronavirus in Ethiopia. The measures enforced by the government to limit social interaction have had a significant impact on those segments of the population who are most observant of religious customs, particularly in a period of time that is dense with such practices. Stressing that the limitations applied also to gatherings of religious nature appeared to be a way for the government to re-assert that the Church constitutes no exception before the law. However, the government did not enforce these measures as strictly as expected, even though – especially during a State of Emergency, as in this case it was in power. For example, the believers who kept gathering in front of churches were tolerated by the police, who would just demand not to stand too close to each other. Additionally, they received a very Christian Easter message from their Prime Minister.

In my view, the ambiguous behavior of the government towards the regulation of religious life seemed to be aiming, on the one hand, at reminding Church leaders of the state’s power to set boundaries to their scope for action. On the other hand, it showed the citizens, especially the community of believers, its tolerance towards their religious practices. As for the Church, at first it supported the governmental regulations, showing its partial commitment to collaborating with the state – and probably taking it as a chance to demonstrate to less-traditional yet influential thinkers, like the Ethiopian diaspora (i.e. Ethiopians and generations of Ethiopians who have left their country due to political, economic or social issues), its will to observe the sanitary norms based on a “modern” biomedical perspective on the disease. As soon as Easter came closer, though, the Church felt its followers’ dissatisfaction about the prohibition of entering the churches’ compounds. Therefore, it hurried to show its concern for the community of believers and its commitment to preserve the ordinary practices by requesting the ban to be loosened. This way, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church made sure its voice was heard by the government, reaffirming its importance in the political arena because of the authority that people entrust to it.

Managing the coronavirus offered both the Church and the State an occasion to remind each other of their respective domains of power and the extent of their influence on the people. While they both directly addressed each other through official means such as provisions and letters, they made not the same effort to support their own declarations with coherent actions. In this constellation, as part of the wider subject (the Ethiopian population) the community of believers constitutes a significant third party, whose support both the government and the Church have been trying to gain, taking the occasion to strengthen their own coherence in such a moment of political uncertainty.

First submitted on 06/05/2020, revised version from 29/05/2020.

Alice Colombo is a social worker for a charity organization focused on supporting disabled and HIV-positive children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She completed her M.A. in Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences at the University of Milan-Bicocca. Her thesis explores the cultural and social dimension of disability in Addis Ababa, examining the impact of gender and socio-economic status on people with disabilities’ understanding of their condition. She can be contacted at: alicecolombo94@gmail.com.

#Witnessing Corona

This article was simultaneously published on the Blog Medical Anthropology . Witnessing Corona is a joint blog series by the Blog Medical Anthropology / Medizinethnologie, Curare: Journal of Medical Anthropology, the Global South Studies Center Cologne, and boasblogs.

Footnotes

[1] Even if I am not going to deepen the topic in this contribution, it must be taken into account that this choice occurred at a delicate moment for the country, since elections were planned for the end of August and the current legislature will expire in September.

References

Addelson, Kathryn P. 1983. The man of professional wisdom. In: Harding, Sandra & Marryl B. Hintikka (eds.). Discovering reality. Feminist Perspectives on Epistemology, Metaphysics, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company, 165-186.

Ancel, Stéphane & Eloi Ficquet. 2015. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) and the Challanges of Modernity. In: Prunier, Gérard & Eloi Ficquet (eds.). Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi. London: Hurst & Co., 63-91.

Borkena. 2020. Ethiopian Orthodox Patriarch isolating for prayer, fasting as COVID 19 case increases. https://www.borkena.com/2020/04/01/ethiopian-orthodox-patriarch-isolating-for-prayerfasting-as-covid-19-case-increase/. Last access: 18/05/2020.

Chaillot, Christine. 2016. The Role of Pictures, the Veneration of Icons and the Representation of Christ in Two Oriental Orthodox Churches of the Coptic and Ethiopian Traditions. In: Studies of the Department of African Languages and Cultures 50, 101-114.

De Ménonville, Siena. 2018. In search of the debtera: An intimate narrative on Good and Evil in Ethiopia today. In: Journal of Religion in Africa 48, 105-144. [doi:10.1163/15700666-12340130]

Fana BC. 2020a. Ethiopia suspends schools, sporting events due to coronavirus. https://www.fanabc.com/english/ethiopia-suspends-schools-sporting-events-for-15-days-due-to-coronavirus/. Last access: 07/05/2020.

Fana BC. 2020b. PM extends Easter message to Ethiopian Christians. https://www.fanabc.com/english/pm-extends-easter-message/. Last access: 07/05/2020.

Fasil, Mahlet. 2020. EOTC requests emergency decree loosening on gathering on Maundy Thursday, Easter Sunday. http://addisstandard.com/news-eotc-requests-emergency-decree-loosening-on-gathering-on-maundy-thursday-easter-sunday/. Last access: 07/05/2020.

Grierson, Roderick (ed). 1993. African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia. New Haven: Yale Univeristy Press.

Index Mundi. 2020. Ethiopia Religions. https://indexmundi.com/ethiopia/religions.html. Last access: 13/05/2020.

Marks, Simon. 2020. Worshippers in Ethiopia defy ban on large gatherings despite coronavirus. https://www.voanews.com/science-health/coronavirus-outbreak/worshippers-ethiopia-defy-ban-large-gatherings-despite?amp. Last access: 07/05/2020.

Office of The Prime Minister. 2020. Proclamation 3/2020: A State of Emergency Proclamation Enacted to Counter and Control the Spread of COVID-19 and Mitigate Its Impact. https://www.abyssinialaw.com/quick-links/item/1928-covid-19-and-ethiopian-state-of-emergency. Last access: 29/05/2020.

Pili, Eliana. 2009. Ayna tela: The shadow of the eye. Healers and traditional medical knowledge in Addis Ababa. In: Ege, Svein, Harald Aspen, Birhanu Teferra & Shiferaw Bekele (eds.). Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies. Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 337-348.