Gendered Objects – Gendered Collecting:

How Colonial Missionary Masculinity Has Structured Ethnographic Collecting

Missionaries were prolific collectors of ethnographic objects for Western museums. Yet the characteristics of missionaries’ collecting and knowledge are rarely given sufficient scrutiny. My aim is to demonstrate why examining missions and their characteristic masculinities is important for understanding colonial ethnographic collecting. These masculinities inscribed themselves into collecting and collections. Why masculinities? Because the religiously defined self-perceptions of missionaries and the often very distinct masculinities connected to them structured the “deep contexts” of collecting. Regarding my case study, the Benedictine mission in Southeast Tanzania, “deep” refers to a several-decades-long conflict that involved a variety of local actors. It was rooted in strong moral and religious convictions and gendered self-perceptions. The distinct version of colonial masculinity guided the cultural boundary-making between European missionaries, African Christians and local communities, but also other European colonialists. The collecting expedition was embedded in this deep context and the collected objects attained significance in a conflict that came out of and was fueled by gendered and racialized identification and boundary-making. In the further trajectories of the collected objects as part of a larger collection and exhibition in a European museum, this deep colonial and gendered context was silenced. The objects became, first, detemporalised (signifying “primitive life and culture”) and then aestheticised (signifying “master pieces of African art”) towards the end of the 20th century.

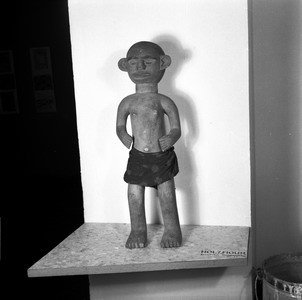

I focus on a set of objects collected in 1927/28 by the ethnographer and Benedictine missionary Meinulf Küsters (1890–1947). They include three circumcision knives, several antelope horns for wound-dressing powder, a wooden pipe box, two pearly hats, a medicine horn, skirts of dry grass, two rain sticks for boys, four wooden sculptures (female), and a wooden sculpture (bush spirit). The objects were used during the initiation procedures known as Unyago and were collected in Southeast Tanzania among Mwera communities at Mnero and Ndanda. They were included in a larger collection gathered by Küsters and numerous local missionaries and mission teachers. Küsters’ expedition was commissioned by the Munich Ethnographic Museum (today: Museum Fünf Kontinente), where the Benedictine monk worked as an assistant director. In addition, the expedition produced filmed material, photographs, and sound recordings. At the same time, Küsters functioned as the mission’s school inspector, thus traveling and supervising several 100 teachers employed by the mission. The mission had arrived in East Africa in 1887. Today, several Benedictine monasteries still exist in Tanzania and Kenya.

Exhibition “Collection East Africa Expedition Dr Küsters” (1929), Ethnographic Museum Munich. Photograph: Author’s personal file, M. Küsters, Archive St. Ottilien Abbey.

Deep context, deep conflict: the Benedictine mission in Southeast Tanzania

The mission’s leadership tried to suppress initiations (Unyago), which they saw as “pagan” and deeply immoral. Arguably the largest single complex of missionary ethnography in the Benedictine mission field consisted of enquiries into the initiations of the Mwera, Makua, Makonde and Yao. In the summer of 1908, the revelations of the young African teacher Innocent Hatia triggered a “moral panic” that rolled over the mission in the second half of 1908. Innocent was the son of the Mwera leader Hatia IV. who had been severely punished by the German colonial government, because he had participated in the Maji Maji war against colonial occupation. His son been became his successor as community leader (“chief”, “Mwenye”) in the 1920s and remained a pillar of local Catholic community in the following decades. The Benedictines interpreted Innocent’s narrative of Unyago, primarily as sex education and physical preparation for indecent sexual intercourse (it included: boys’ circumcision; girls’ genital cutting; manipulation and extension of the female genitalia). The results were pressing enquiries among African mission personnel, violent intervention in the actual initiations, and urgent supplications to colonial authorities. The oppressive policies of the mission – which in effect stalled evangelization and put converts in a difficult situation, forcing them to break with their families and communities, or resort to secrecy – lasted for decades, until in the late 1930s African Christians and Benedictine mission leaders agreed on a Christian version of Unyago.

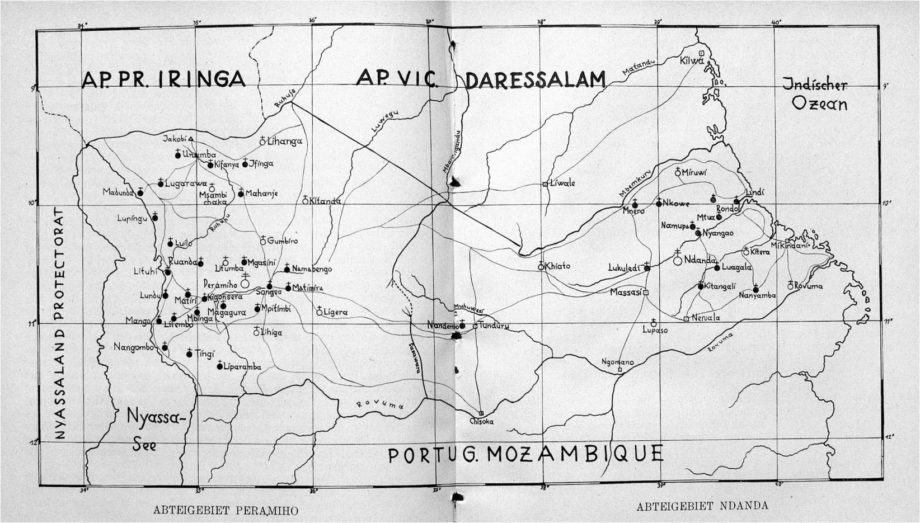

Benedictine missions in Southern Tanganyika, from: H. Meyer, Wir besuchen unsere Missionare, Missionsblätter 42 (1938), 144f.

Mission theology, celibate masculinity, and racial segregation

The fierce reaction of European missionaries was fueled by the fear that deeply ingrained traditions and deviant intimacies would taint the fundamentals of Christian faith and communities. Intimacy was at the heart of missionaries’ engagement with ethnographic knowledge production and collecting. Once a mission had successfully evangelized communities, the focus would shift to pastoral care, in order to guide communities along largely Eurocentric moral pathways. In the colonial and Catholic context pastoral work attempted to enforce (by physical violence, social, or religious exclusion) a narrow moral codex based on neo-scholastic theologies, which upheld a paternalistic, monogamous family and household ideal, and saw physical intimacy legitimate solely for procreative purposes.

These theologies teamed up with a form of colonial masculinity which distinguished itself from African Christians and other male European colonialists. Adhering to strict monastic vows the missionary monks claimed a superior status, affected neither by the moral and psychological crisis of European masculinity in the tropics (“Tropenkoller”), nor the constant urge to return to the “primitive” and “pagan” ways that allegedly endangered African Christians. To put it bluntly, Catholic missionary masculinity and its claim to superiority rested on the conviction that they themselves were in control of their intimate urges regarding women while others were not. Widespread prostitution and extramarital relations seemed to attest to the inferiority of other male European colonialists, the persistence of initiations supposedly underlined the continuity of “paganism” and immorality among African Christians of all genders. Celibate monastic masculinity already afforded extensive boundary-work in Europe. This was even more so the case in colonial Africa, were religious, gendered, and racialized forms of “othering” intersected. As a result, the church hierarchy and the Benedictine monasteries remained segregated by gendered (until today) and racialized criteria (until the 1980s), while African Christian communities remained under scrutiny and suspicion for many decades.

Collecting and long-term trajectories of the collected objects

The collecting process enacted by Küsters proceeded in a climate of conflict and secrecy. Mission teachers, who were doing the actual acquisition, were liminal figures, negotiating a narrow path between losing their livelihoods from the mission and alienating their families and constituencies. But they were also intermittent figures of authority in the local colonial society who channeled communication with and access to the socially and economically powerful missions. In Munich, the objects were classified, catalogued, and stacked in the museum depots – after having been presented to the public in a grand, if rather unsystematic exhibition in 1929. The wooden sculptures alone resurfaced in several exhibitions as “African art” during the second half of the 20th century.

Exhibition “African Art”, Amerika-Haus, Munich 1953; Photograph: Felicitas Timpe, Picture Archive Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CCO 1.0

To conclude: I have highlighted the deep, both gendered and racialised, context of missionary collecting. The case study discussed objects which were connected to the initiation procedures of the Mwera communities of Southeast Tanzania and collected during an expedition in 1927/28 for the Munich Ethnographic Museum by the ethnographer-monk Küsters. The process of collecting and the objects themselves were invested with meaning by the mission’s perception of initiation as a sinful and immoral reproduction of paganism threatening the integrity of African Christian communities. Missionary collecting as illustrated here was thus embedded in Eurocentric, physically and epistemically violent cultural practices and colonial cultures of religious and cultural superiority which rested on the self-perception of a superior masculine self-control.

Richard Hölzl is lecturer at the Seminar for Medieval and Modern History, University of Göttingen. His research fields include the environmental history of modern Europe and the history of German and European colonialism, incl. Christian missions. Recent publications: Gläubige Imperialisten. Katholische Mission in Deutschland und Ostafrika, 1830-1960 (Frankfurt: Campus 2021) and ed. with KJ Osthoek, Managing Northern Europe’s Forests. Histories from the Age of Improvement to Age of Ecology (New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2018).

About the DCNtR Debate #1: It has long been accepted that colonialism had a distinctive epistemic dimension, which was upheld by disciplines such as social anthropology and other knowledge-making projects. Under this colonial episteme, people and human experiences were hierarchically classified according to racial categories and ethnography and ethnographic collecting were key components in these processes. However, the colonial regime did not only rely on race as an organising category, but also on gender. The first debate in the DCNtR Debates series tackles this question with seven contributions from around the world which explore the relationship between the gender of the collector, the gender of those collected from and consequences of these gendered practices of collecting for the epistemic practices of display in today’s museums.

Selected further reading:

Patrick Harries, David Maxwell (eds.), The Spiritual in the Secular: Missionaries and Knowledge about Africa. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2012.

Richard Hölzl, „Arrested Circulation: Catholic Missionaries, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Politics of Cultural Difference in Imperial Germany, 1880-1914. In: Anxieties, Fear and Panic in Colonial Settings: Empires on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, ed. by Harald Fischer-Tiné, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2017, 307-344.

Richard Hölzl, “Educating Missions. Teachers and Catechists in Southern Tanganyika, 1890s to 1940s,” Itinerario 40 (2016) 3, 405-428.

Jens Jahn (ed.), Tanzania. Meisterwerke Afrikanischer Skulptur. Sanaa Za Mabingwa Wa Kiafrika, Munich: Jahn 1994.

Maria Kecskési (Hg.), Die Mwera in Südost-Tansania. Ihre Lebensweise und Kultur um 1920 nach Joachim Ammann OSB und Meinulf Küsters OSB mit Fotografien von Nikolaus von Holzem OSB, Munich: Utz 2012.

Valentin Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of African: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge, London et al.: James Curry, 1988.