Challenges of rewriting the Khomani San/Bushman archive at Iziko Museums of South Africa

After many years of discussion and deliberation the controversial Ethnographic Gallery at Iziko South African Museum was finally de-installed on 15 September 2017. The response to the decision elicited an interesting and conflicting range of responses. Several members of the public, including Khoisan descendants, complained about the closure, while a number of Khoisan chiefs and Khoisan descendants commented that the closure was overdue. A retired historian from the University of Cape Town argued that it was a ‘grave mistake’ to close the diorama as it could be used ‘to show the history of what colonialism did to the hunters and herders of the Cape’.[1] A group of doctoral students staged an intervention, closing the Ethnographic Gallery space off with tape declaring the space to be “A colonial crime scene” and holding a performance, “Ndabamnye neenkumbulo nemiphefumlo enxaniweyo” (I became one with memories and thirsty souls). The curators of the intervention argued that ‘the objects in the gallery are in fact evidence of colonial crimes and require decolonial investigation’.[2]

Objects of San [3] material culture and photographs were collected from the early formation of the South African Museum (now the Iziko South African Museum) which was established in 1825. Ciraj Rassool has pointed out that the collecting of artefacts relating to the San was carried out alongside the ‘plunder of graves’. He argues that ‘these collections and records were assembled in the attempt to study pasts without memory’ that were active and effective in the present’.[4] In considering how to rewrite the colonial archives linked to our social history collections at the Iziko Museums, we have to acknowledge and interrogate the violence and racism that, in a sense, is a stain on the Khomani San collections in our museums. We also have to acknowledge the power of museums in creating “knowledge” and “truths” through the selections we make in exhibiting objects of material culture. Patricia Davison points out that “museums give material form to authorized versions of the past, which in time became institutionalized as public memory”.[5] This has been apparent in the responses to the closure of the Ethnographic Gallery. While Ron Martin and other Khoisan descendants were critical of the ethnographic exhibition, which they saw as an insult to Khoisan descendants, I had a conversation with an old lady who objected to the impending closure of the gallery. On the point of tears, she explained to me that she had visited the exhibition as a school pupil and in later years had brought her children to see it and, later, even her grandchildren. I was also asked to respond to a parliamentary question emanating from a visit by a member of parliament of Khoisan descent who had brought two international visitors to the museum to view the Ethnographic Gallery a few months after its closure and had expressed disappointment over the closure. He had submitted a question to parliament requesting an explanation for the closure and an account of who had been consulted in the decision.

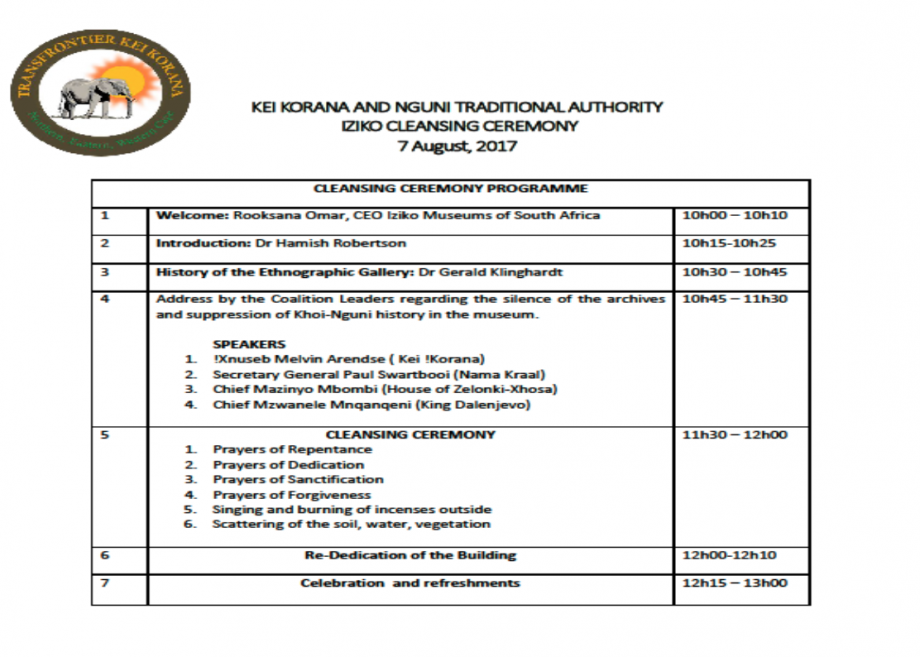

One of the stakeholders we had consulted about the closure of the Ethnographic Gallery was the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni Coalition, who were critical of the ethnographic display and proposed having a cleansing ceremony in the space, which they performed on 7 August 2017, in order to pray for forgiveness, demonstrate repentance for the way in which the history and culture of black peoples had been portrayed and to sanctify the space. One of the questions we face as museum practitioners is how to acknowledge the violence, dislocation and pain that haunts collections such as those of the Khomani San in a way that contributes to healing and social justice. Anne Wanless mentions that amongst the collections donated to the South African Museum by the collector Dr Louis Fourie, Medical Officer for the Protectorate of South West Africa and amateur anthropologist, was a set of manacles used on Bushmen prisoners.[6] These manacles are not part of the San collections but have rather been grouped with the artefacts associated with slavery instead of being part of the narrative of San oppression and dislocation.

There have been shifts within the museums in South Africa, sometimes as a result of and interplay of reflection on practices and relevance and external pressure from government and stakeholders. During the colonial and apartheid period collections relating to the Bantu-speaking groups, Khoi and San were housed at the South African Museum alongside natural history collections, while collections relating to Europe and European descendants as well as to Asia and Asian descendants were housed in the South African Cultural History Museum. Ironically, the South African History Museum, occupying a site that was formerly the site of the Dutch East India Company’s Slave Lodge made virtually no reference to the history of slavery at the Cape. At a Heritage Day address at Robben Island Museum in September 2017 Nelson Mandela, in an often quoted speech, called for transformation of South African museums, stating “When our museums and monuments preserve the whole of our diverse heritage, when they are inviting to the public and interact with the changes all around them, then they will strengthen our attachment to human rights, mutual respect and democracy, and help prevent these ever again being violated”.[7] On 4 December 1998 the Cultural Institutions Act was promulgated, providing for the amalgamation of some of the national museums to form two flagship institutions the Northern Flagship (now Ditsong Museums) in Pretoria and the Southern Flagship (now Iziko Museums) in Cape Town.

The Iziko Museums decided, in an attempt to transform the way in which collections were classified, break down the divisions of the colonial and apartheid past and build diversity in museum representation, to integrate the European, Asian and ethnographic collections as social history collections. However, it has become clear that in order to bring about real integration there is a need to rewrite the museum archive. Documentation accompanying the archive continues to reflect the colonial and apartheid conditions under which these collections were acquired. Various researchers have analysed and published on aspects of these collections. For example, Vibeke Viestad has examined in depth San costume, rejecting the myth of the “naked Bushman” and demonstrating that “far from being naked, or nearly naked, Bushmen of colonial southern Africa had a complex and meaningful practice of dress that was intimately related to subsistence, identity and their perception of how to live life in the world as they knew it”.[8] The Iziko Museums were approached by representatives of the Khomani San in November 2017 with a proposal to hold an exhibition titled ‘Light in the Darkness’ in the space that had formerly served as the Ethnographic Gallery. The Khomani San were in the process of setting up a Creative Collective and in their motivation for the exhibition they stated that it was “a narrative that zooms in on the contemporary relevance of traditional Bushmen world views, unifying Bushmen communities on the one hand, but also the wider global audience that is currently looking to indigenous culture for ways of reconnecting to the natural world and to each other”.[9] The Iziko Museums management pointed out to the Khomani San representatives that a decision had been taken not to exhibit on the Khoi and San in the gallery space until the question of exhibiting on human history alongside natural history had been resolved. The response by the Khomani was that the dichotomy between natural history and human history was a western construct and that the San world view saw humans and nature as one. The proposal was turned down much to the disappointment of the Khomani San representatives. The Collections and Digitisation department saw an opportunity to engage with the Khomani San around the collections and to bring in community narratives to Khomani collections.

Arrangements were made to transport and accommodate four leading members of the Khomani Communal Property Association – Chief Petrus Vaalbooi, traditional leader of the Khomani San, Itzak Kruiper, Lydia Kruiper and Annamarie Vaalbooi. The idea was that the four would spend some time engaging with the collections and in discussion with the Iziko collections staff. We requested permission to record the proceedings via video recorder, which was granted, and a Memorandum of Agreement was concluded around the project. Interestingly the first hurdle we ran into with the project was a challenge from the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni Coalition, who accused us of separating the cultural history of the Khoisan in colonial fashion, arguing that the Khoi and San had always had an interlinked history. We acknowledged that their histories were interlinked but pointed out that we were looking at collections from a particular geographical area. This challenge did however leave an uncomfortable feeling as it raised the question of whether our approach was not ‘ethnicising’ the analysis of the history of indigeneous communities. However, we also needed to acknowledge that the Khomani San were a scattered people who had been brought together for the purposes of a 1999 Land Claim. The South African apartheid government had forcibly removed the Khomani San from their ancestral lands in 1971 and the clan had become widely scattered across the Northern Cape.

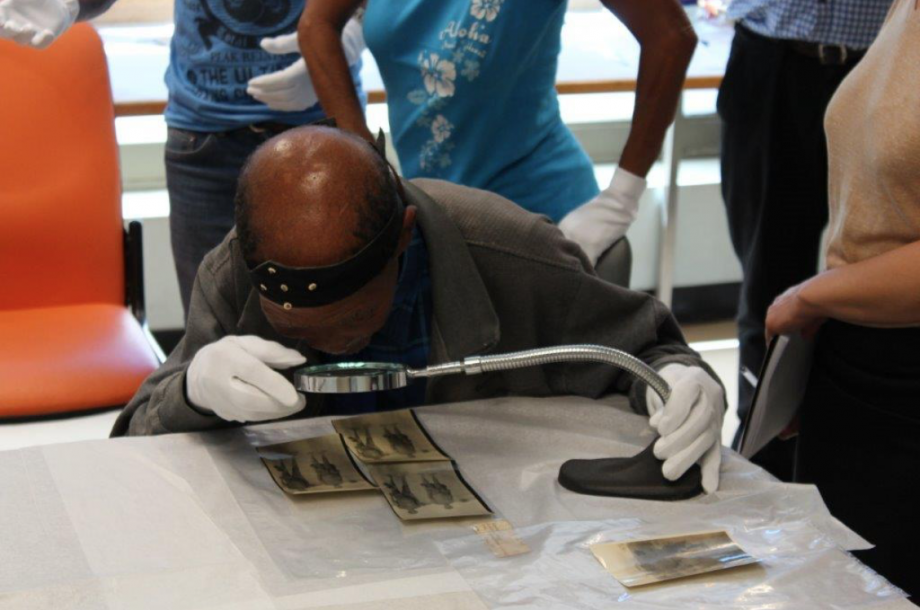

The Iziko Collections and Digitisation department held a preliminary meeting with the Khomani San representatives in December 2018 to discuss the aims and objectives of the workshop around the collections and to agree on logistics and a preliminary programme. The workshop ran from the 4th to the 8th of February 2019 and was conducted in Afrikaans as the delegates did not feel confident in their English. On the first day we revisited the aims and objectives and provided an overview of the social history collections. During the discussions Petrus Vaalbooi expressed concern over the ‘dying of the Nxu language’ arguing that more attention was paid to the preservation of Nama while Nxu speakers were gradually dying out. There was a sense of frustration in that several government departments had been approached but to no avail. As a collections department we unfortunately could not be of much help in this regard. Another issue that was raised was the identity of the San, with Vaalbooi stating that the Bushmen had been subjected to a range of identities that had been imposed on them, form Bushman to coloured to San and that his earlies recollections were of his elders using the term Saa as their self-identity. The first day of the workshop also saw the group examine the various objects in the collections, discuss the memories evoked by the collections and also examine and comment on the information generated by the museum on the objects. Of particular interest were their comments on the objects of spiritual significance such as a whisk that was used during the trance dance and the rattles that were tied around the ankles of the dancers, made from cocoons and containing tiny stones. They explained how the shaman would use the whisk to sprinkle a medicine over each dancer to give them protection and strength to access the spirit world to bring healing. They also commented on the use of tortoise shells to store buchu and other medicinal herbs and the potency of the tortoise shell. In addition, they commented on the bows and arrows used during a hunt. They also mentioned the blunt arrows used in courtship. A suitor would shoot the arrow at his intended partner and if she picked it up and broke it this meant she was not interested in him. If, however, she held it against her heart, this meant she accepted his overtures.

On the second day we began with a reflection of the first day’s activities and this was followed by a continuation of the interaction with the object collections and the catalogue cards linked to the objects. The third day was spent on an examination of and discussion on the photographic collections relating to the Khomani San. During the examination of the photographs the group, in a moment of excitement, began to communicate with each other in Nxu and we had to request that they translate the interaction in Afrikaans. In the Bleek and Lloyd photographic collection the group were able to identify relatives and community members they had known. Lydia Kruiper identified her father, brothers and other community members who had been photographed during a healing ceremony as well as during hunts. She was able to provide background information on her family and other community members. Petrus Vaalbooi identified his mother, Elsie Vaalbooi, who had been a fluent Nxu speaker and a member of the Khomani San Council of Elders. She passed away in 2002. Petrus and his mother had been involved in an initiative to trace surviving Nxu speakers in the Northern Cape. One of the interesting comments made by Petrus Vaalbooi was that, contrary to the images projected of the San, his grandfather rode a horse, hunted with a gun and was a sheep farmer.

The fourth day was dedicated to a visit to the Iziko South African Museum where the group did a walk-through of the rock art gallery and reflected on the messages associated with the different rock art paintings. They also visited the Mammal Gallery and the Discovery Room. As Petrus Vaalbooi had expressed an interest in assisting the Iziko Museums with resolving the question of the restitution of human remains we held a meeting with the Executive Director of Core Functions to discuss possible areas of collaboration. The group offered to speak to other groups, including the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni-Coalition to encourage all to come around the table in the interests of reburying the human remains as they found it deeply disturbing to think of their ancestors lying in boxes in museums. They also suggested that the San Council be involved in deliberations as they are meant to represent the interests of all San groups in South Africa.

The final day was spent on an oral history interview with the group, followed by a discussion around a way forward. We had been considering how we could broaden such an exercise to include other San groups, as well as Khoi groups. Interestingly, this was also an issue that was raised by the Khomani San group. We also considered how the issues discussed during the workshop could be taken back to the broader community in the Kalahari, given the challenges of distance – one-thousand-and-seventy-nine kilometers to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park to Cape Town. We provided the group with images of the object collections and copies of the photographic collections and also wrote up a report which was sent to the San Council so that the community could receive some feedback from the museum. Other factors to consider were the lack of electricity and the high rate of illiteracy within the community. We are hoping that we can build on this exploratory project and, together with the Khomani group, reach out to other Khoisan groups to open the museum collections to communities and bring in community narrative to these collections. One of our concerns is that while museums focus on the past history of the Khoi and San, there is little focus on the resurgence of San and Khoi identity and on how the past speaks to the present. There is a sense of frustration amongst the indigenous communities as museums are perceived to have neglected their histories. There is little or no contemporary collecting taking place around the material culture of the San and Khoi descendants. There is also a need for a dynamic oral history project that can trace the narratives that have been handed down through generations.

In attempting to rewrite the museum archives we have to consider not only the language and content of the archives but also the collections that raise ethical questions. For example, we know of at least one artefact, a skin bag that was in the ownership of one of the San prisoners used in the Ethnographic Gallery casting project. Given the violence and racism that were an integral part of the making of the San casts in the exhibition diorama, how should such artefacts be treated? This also raises the question of how much research has been conducted into how the collections were acquired. We need to research all of collectors who sold or donated collections to the museums to try to understand how these items may have been acquired. Vibeke Viestad’s study makes mention of “photographs of naked people taken by Dorothea Bleek” in the South African Museum collections, though she adds that “these have of course never been published online unlike her other field photographs”.[10] What are the rights of descendant communities when faced with photographs that violate their ancestors? As a collections department tasked with the digitising and care of the collections we realise that the rewriting of the museum archives is a massive task that calls for partnerships that can provide valuable research assistance. In order to truly integrate the social history collections we need to fill the gaps not only in the collections but also in the knowledge surrounding the collections.

Paul Tichmann is a doctoral student in the History department at the University of the Western Cape. He is the Director of the Collections and Digitisation department at the Iziko Museums of South Africa and was formerly the curator of the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum in Cape Town. His areas of focus include labour history, slave history and South African history. He has worked in the museums sector for twenty years. His employment history includes working as a Researcher at the University of Durban-Westville’s Institute for Social and Economic Research and as a Course Writer and Educator in the Labour and Community Resources Project of the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) Trust. He has an MA Degree in Economic History from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa.

[1] Cape Times, 16 August 2017, p.9

[2] Art Africa, Curating the Colonial Crime Scene: Heritage & Violence of Ethnographic Racism, January 30, 2018

[3] Some indigenous communities prefer to be identified as ‘Bushman’ rather than ‘San’. A number of researchers have commented on the fact that both of these terms are problematic, having been thrust on communities and that some indigenous communities prefer to ‘self-identify’.

[4] Ciraj Rassool, Re-storing the Skeletons of Empire,: Return, Reburial and Rehumanisation in South Africa, Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 41 (3), 2015, p.654

[5] Patricia Davison, Museums and the Reshaping of Memory, in Sarah Nuttall and Carli Coetzee (eds), The making of memory in South Africa, Cape Town, 1998, p.186

[6] Ann Wanless, The Silence of Colonial Melancholy, A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Johannesburg, 2007, p.20

[7] Address by President Mandela on Heritage Day, 24 September 1997, www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=4215

[8] Vibeke Maria Viestad, Dress as Social Relations: An Interpretation of “Bushmen Dress” as represented in the Bleek & Lloyd, Dorothea Bleek and Louis Fourie collections in South Africa, Vol. 1, 2014, p.21

[9] ‘Light in the Darkness’ exhibition proposal submitted to Iziko by Hugo Bodenham, 3 November 2017

[10] Vibeke Maria Viestad, Dress as Social Relations: An Interpretation of “Bushmen Dress” as represented in the Bleek & Lloyd, Dorothea Bleek and Louis Fourie collections in South Africa, Vol. 1, 2014, p.40