Challenges of Re-Writing the Iziko Ethnographic Collections Archives: Some Lessons from the Khomani San/Bushmen Engagement

DCNtR Debate #3. The Post/Colonial Museum

The authors of this article are both museum professionals within the Iziko Museums and as such have come to inherit the ›skeletons in the cupboard‹. We would prefer to believe that, having been active participants in the struggle against apartheid and wrestling with issues of identity in post-apartheid South Africa, we have a critical approach in our museum practice. However, as insiders of an institution that has roots in the colonial and apartheid eras and which continues to wrestle with transforming its structures, practices, and content, we cannot avoid complicity. The dilemma we face, then, is how to be agents of transformation while, at the same time, being part of an institution that has its foundations in colonialism and apartheid.

Achille Mbembe argues »Archiving is a kind of internment, laying something in a coffin, if not to rest, then at least to consign elements of that life which could not be destroyed purely and simply« (Mbembe 2002: 22). He further argues that the process of assigning materials to archives gives such materials an unquestionable authority that neutralises the violence and cruelty of the ›remains‹ (cf. ibid.: 22). This certainly holds true for much of the ethnographic collections in South African museums. While several museums in South Africa grapple with the reburial of human remains in their collections, a spectre from the colonial past, the equally important task of interrogating the museum archives, linked to ethnographic collections, is yet to be adequately addressed.

Laura Gibson contends that South African museums have failed to interrogate the ›rules of practice‹ for constructing knowledge, pointing out that »cataloguing, classifying and collecting processes are the foundational level at which museums produce knowledge« (Gibson 2019: 25). Similarly, Leslie Witz et al. argue that in South Africa the museum has failed »to critically examine its own history of collecting« and museums, therefore, remained trapped in their »classificatory system in which the exhibitionary and ethnographic work« (Witz et al. 1999: 13) remains separate from notions of history. There is often a tendency to separate museum collections from the idea of archives, and museums have neither confronted their collecting practices nor systematically interrogated the museum documentation or archives. Witz criticizes that museums, instead of interrogating their classificatory formations, opted to become inclusive by simply adding more »voices, objects and explanations to give them the authority of a factual past« (Witz 2012: 13). Contributing to this argument, Steven Dubin argues that museums were »playing catch up, striving to fill in what they recognize as wide gaps in their holdings« (Dubin 2009: 5). In attempting to enact transformation in democratic South Africa, the tendency has been for museums to adopt an add-on approach that seeks to ›fill the gap‹ by bringing in some new narratives and interpretations rather than critically engaging with the flawed narratives that are part of their legacy of colonialism and apartheid. These add-ons, according to Witz et al., allowed museums to insert themselves into the discourse on »South Africa’s public history and the heritage of all citizens« (Witz et al. 1999: 12). Rogoff, furthermore, argues that the add-on effect is carried forward by the »belief that we can simply insert other histories into a grand narrative of Modernism and ignore the conflict between hegemonic and marginally-located cultures« (2002: 5).

As Gibson states, »we need to understand not only the types of narratives that are told by the museum’s collections and documentation but also why and how others are (still) excluded« (Gibson 2019: 236). If museums want to meaningfully engage with cultural diversity and decolonize their collections, classificatory and exhibitionary practices, and processes, they have to »recognize the shift from the compensatory projects of atoning for absences and replacing voids, to a performative one in which loss is not only enacted, but is made manifest from within the culture that has remained a seemingly invulnerable dominant« (Rogoff 2002: 3).

A focus on the ethnographic archive at the Iziko Museums cannot avoid acknowledging the complexities of the human remains, which form part of these collections. Ciraj Rassool (2015: 654) has pointed out that the collecting of artefacts relating to the San, now located in our museum, was carried out alongside the ›plunder of graves‹. Legassick and Rassool (2000) have demonstrated the involvement of museums in South Africa in the trade in human remains for purposes of racial science during the colonial period. They also suggest »it might be the case that the entry of such remains into museums and such racial research at the beginning of the twentieth century were at the centre of the transformation of the museum in South Africa as an institution of order, knowledge and classification« (Legassick/Rassool 2000 1f.). To what extent are we still bound by these systems of »order, knowledge, and classification«?

An innovative attempt to raise critique concerning museum classification and knowledge production came in the form of the exhibition Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushmen, curated by Pippa Skotnes and installed at the South African National Gallery in 1996. The exhibition attempted, through a strong visual display that included body casts, photographs, anthropological field notes and museums accession notes, to critique the misrepresentation and dehumanisation of the Bushmen in museums in South Africa. Thus the curator intended to make Western scientific practices inherited by museums visible and bring into question museum practices related to human remains and the representation of ›other‹ cultures. In a review on the exhibition, Michael Morris argued that the exhibition would »invigorate difficult debates in cultural museum circles on displaying human remains to illustrate and explain the identity, nature and culture of people« (Morris 1996). Though the exhibition was met with ambivalence, it provoked substantial debate and dialogue on the representation of San material culture and human remains. In its Sunday Culture column, the Sunday Independent of 26 May 1996 pointed out that the exhibition provoked »animated and heated debate in the media and in university seminars and staff tearooms. In addition, a plethora of local groups had emerged claiming to be descendants of the Khoisan and the legitimate representatives and custodians of Khoisan past« (Sunday Independent 1996: 23). In many of the reviews on the exhibition, Skotnes was severely criticised and her motives questioned. She was accused of ›self-promotion‹, of being ›insensitive‹, and of ›appropriation‹ and ›recolonization‹ of history. On the other hand, there were some who »wholeheartedly endorsed and praised« the Miscast exhibition (ibid.: 26). Some critics classified the exhibition as thought-provoking, raising both genuine praises and concerns (ibid.). Irrespective of its reception, the exhibition’s success can be measured in the dialogue on transformation and identity it brought into the public domain. It forced people to rethink how they were classified as well as how knowledge concerning their history and culture is produced, interpreted and narrated.

The Iziko Museums have come to inherit these human remains, procured by the South African Museums, and the challenge is to restore dignity and humanity to these remains as well as to the descendants, including Khoi, San and Nguni communities.[1] Objects of San[2] material culture, human remains, and photographs were collected from the early formation of the South African Museum (now the Iziko South African Muse- um), which was established in 1825. Ciraj Rassool points out that »these collections and records were assembled in the attempt to study pasts without memory that were active and effective in the present« (Rassool 2015: 654). Human remains and grave goods were collected and incorporated into the ethnographic collections of museums as objects, either for display or in pursuit of ›racial science‹. These indigenous San objects, human remains, and grave goods were framed through the scientific lens of anthropology and archaeology, and were incorporated into museums as ethnographic collections. In South African museums indigenous objects and remains were collected and »exhibited in natural history museums, as opposed to cultural history museums or art museums« (Coombes 2003: 209). This was to »illustrate the progress made by European civilization and the white race, compared to primitive cultures« (Gore 2004: 33). It is this agency of power and authority over the production and dissemination of knowledge that has to be interrogated, investigated and re-interpreted in the post-apartheid museum. Indigenous communities started demanding representation in museum narratives but also wanted to become active participants in the rewriting of the colonial archive, represented through museums as well as government archives, which had ›locked them in time‹. These demands created tension between the colonial archive represented through museums as well as state archives, and the post-apartheid mandate of an inclusive archive which purports representation of the nation’s diverse history. In addition, these demands are linked to reclaiming identity, language, culture, and the restoration of dignity, as well as to the need for an alternative voice to the narratives of colonialism and apartheid.

The Iziko Museums hold 195 unethically-collected human remains, including a number of body casts and moulds. The human remains and casts are not available for exhibition, research or viewing. The Iziko Museums developed a human remains policy in 2002 in an attempt to chart a way forward for the reburial and repatriation of human remains. However, the process of restitution and repatriation has been hampered by, amongst other challenges, the lack of a national policy and legislation for restitution and repatriation, incomplete documentation on the remains collected, and lack of a budget to cover the costs of consultation and reburial ceremonies. A positive step towards reburials was recently taken through a collaborative project involving the Iziko Museums, the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC), the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), the Khoi-Boesman, and the Nguni Coalition, all in relation to the so-called Colesberg 52. At the time of the Miscast exhibition, a Griquas group lobbied the government in an effort to focus attention on their ancestral burial graves and called for the reburial of the »Colesberg remains« (Maykuth 1996). The Colesberg 52, victims of a smallpox epidemic in 1866, were exhumed from a grave outside Colesberg in the Northern Cape and incorporated into the South African Museum collections for purposes of ›race-based science‹. According to Tanya Peckmann »these individuals were probably an indigenous Khoe community who lived on the outskirts of town but provided the rural and urban population with a cheap source of labour« (Peckmann 2003: 290). The Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown unfortunately thwarted plans to hold a consultation meeting with the community of Colesberg planned for 22 March 2020.

In considering how to rewrite the colonial archives linked to our social history collections at the Iziko Museums, we have to acknowledge and interrogate the violence and racism that is, in a sense, a stain on the Khomani San collections in our museums. We also have to acknowledge the power of museums in creating ›knowledge‹ and ›truths‹ through the selections we make in exhibiting objects of material culture. Patricia Davison points out that »museums give material form to authorized versions of the past, which in time became institutionalized as public memory« (Davison 1998: 145).

After many years of discussion and deliberation, the controversial Ethnographic Gallery at Iziko South African Museum was finally de-installed on 15 September 2017. The decision elicited a range of interesting and conflicting responses. While a number of Khoisan chiefs and descendants asserted that the closure of the gallery was overdue, several members of the public, including some Khoisan descendants, complained about the closure. A retired historian from the University of Cape Town argued that it was a »grave mistake« to close the diorama as it could be used »to show the history of what colonialism did to the hunters and herders of the Cape« (Smith 2017: 9). One group of doctoral students staged an intervention, closing the Ethnographic Gallery space off with tape declaring the space to be »A colonial crime scene« and holding a performance; Ndabamnye neenkumbulo nemiphefumlo enxaniweyo (I became one with memories and thirsty souls). The curators of the intervention argued that »the objects in the gallery are in fact evidence of colonial crimes and require decolonial investigation« (Art Africa 2018).

One of the stakeholders we consulted about the closure of the Ethnographic Gallery was the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni Coalition, which was critical of the ethnographic display and proposed a cleansing ceremony in the space. They then performed the ceremony on 7 August 2017, in order to pray for forgiveness, demonstrate repentance for the way in which the history and culture of black peoples had been portrayed, and to sanctify the space. The Khoi-Boesman-Nguni Coalition was formed around March 2017 to campaign for the return of human remains. »Led by Chief Melvin Arendse of the Kei Korana, the Coalition brought together Khoi-, San- and Xhosa-speaking groups. Chief Arendse asserted that the ›Nguni and Khoi‹ had a long history and formed the first alliances against colonialism« (Evans 2017).

One of the questions we face as museum practitioners is how to acknowledge the violence, dislocation and pain that haunts collections such as those of the Khomani San in a way that contributes to healing and social justice. Anne Wanless has indicated that a set of manacles, used on Bushmen prisoners, was amongst the collections donated to the South African Museum by the collector Dr Louis Fourie, Medical Officer for the Protectorate of South West Africa and amateur anthropologist (cf. Wanless 2007: 20). These manacles are not part of the San collections. Instead, they have been grouped with artefacts associated with slavery as opposed to falling within the narrative of San oppression and dislocation. This kind of unremembering of history testifies to the ways in which colonial archives were twisted, falsified, and or marginalized. If we wish to decolonize the colonial archive, we need to interrogate processes and practices that lead to such unremembering, while beginning a process of correcting such historical falsifications.

There have been shifts within the museums in South Africa. These have variously occurred as both a result and interplay of reflections on particular practices and their relevance, as well as external pressure from the government and relevant stakeholders. During the colonial and apartheid period, collections relating to the Bantu-speaking groups, Khoi and San, were housed at the South African Museum alongside natural history collections, while collections relating to Europe and European descendants, as well as to Asia and Asian descendants, were housed in the South African Cultural History Museum. Ironically, the South African History Museum, occupying a site that was formerly that of the Dutch East India Company’s Slave Lodge, made virtually no reference to the history of slavery at the Cape. In an often-quoted speech given during a Heritage Day address at Robben Island Museum in September 1997, Nelson Mandela called for the transformation of South African museums, stating that

»when our museums and monuments preserve the whole of our diverse heritage, when they are inviting to the public and interact with the changes all around them, then they will strengthen our attachment to human rights, mutual respect and democracy, and help prevent these ever again being violated« (Mandela 1997).

On 4 December 1998 the Cultural Institutions Act was promulgated, providing for the amalgamation of some of the national museums to form two flagship institutions: the Northern Flagship (now Ditsong Museums) in Pretoria and the Southern Flagship (now Iziko Museums) in Cape Town.

The Iziko Museums decided, in an attempt to transform the way in which collections were classified, to break down the divisions of the colonial and apartheid past and build diversity in museum representation, to integrate the European, Asian and ethnographic collections as social history collections. However, it has become clear that in order to bring about real integration, museum archives needed to be rewritten. Documentation accompanying the archive continues to reflect the conditions of colonialism and apartheid under which these collections were acquired. Various researchers have analysed and published on aspects of these collections. For example, Vibeke Viestad has examined San costume in depth, rejecting the myth of the ›naked Bushman‹ and demonstrating that »far from being naked, or nearly naked, Bushmen of colonial southern Africa had a complex and meaningful practice of dress that was intimately related to subsistence, identity and their perception of how to live life in the world as they knew it« (Viestad 2014: 21).

The Iziko Museums were approached by representatives of the Khomani San in November 2017 with a proposal to hold an exhibition titled Light in the Darkness in the space that had formerly served as the Ethnographic Gallery. The Khomani San were in the process of setting up a creative collective and in their motivation for the exhibition they stated that it was »a narrative that zooms in on the contemporary relevance of traditional Bushmen world views, unifying Bushmen communities on the one hand, but also the wider global audience that is currently looking to indigenous culture for ways of reconnecting to the natural world and to each other« (Bodenham 2017: 1). The Iziko Museums management pointed out to the Khomani San representatives that a decision had been taken not to exhibit on the Khoi and San in the gallery space until the question of exhibiting on human history alongside natural history had been resolved. The response by the Khomani was that the dichotomy between natural history and human history was a Western construct and that, in the San worldview, humans and nature are one. The proposal was turned down, much to the disappointment of the Khomani San representatives. The Collections and Digitisation department saw an opportunity to engage with the Khomani San around the collections and to bring in community narratives to Khomani collections.

Arrangements were made to transport and accommodate four leading members of the Khomani Communal Property Association – Chief Petrus Vaalbooi, traditional leader of the Khomani San, Itzak Kruiper, Lydia Kruiper and Annamarie Vaalbooi. The idea was, that the four would spend some time engaging with the collections and in discussion with the staff for the Iziko collections. We requested permission to record the proceedings via video recorder, which was granted, and a Memorandum of Agreement was concluded around the project. Interestingly, the first hurdle we ran into with the project was a challenge from the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni Coalition, who accused us of separating out the cultural history of the Khoisan, in a colonial fashion, arguing that the Khoi and San had always had an interlinked history. We acknowledged that their histories were interlinked but pointed out that we were looking at collections from a particular geographical area. This challenge left an uncomfortable feeling, however, as it raised the question of whether our approach was not ›ethnicising‹ the analysis of the history of indigenous communities. In addition, the inadequate and/or falsified recording of information in the colonial archive posed additional challenges in reconfiguring the archive. However, we also needed to acknowledge that the Khomani San were a scattered people who had been brought together for the purposes of a 1999 Land Claim. The South African apartheid government had forcibly removed the Khomani San from their ancestral lands in 1971 and the clan had become widely scattered across the Northern Cape.

The Iziko Collections and Digitisation department held a preliminary meeting with the Khomani San representatives in December 2018 to discuss the aims and objectives of the workshop around the collections and to agree on logistics and a preliminary programme. The workshop ran from the 4th to the 8th of February 2019 and was conducted in Afrikaans as the delegates did not feel confident in their English. On the first day we revisited the aims and objectives and provided an overview of the social history collections. During the discussions, Petrus Vaalbooi expressed concern over the »dying of the Nxu language«, arguing that more attention was paid to the preservation of Nama while Nxu speakers were gradually dying out. There was a sense of frustration in that several government departments had been approached but to no avail. As a collections department, we unfortunately could not be of much help in this regard. Another issue raised was the identity of the San, with Vaalbooi stating that the Bushmen had been subjected to a range of identities that had been imposed on them, from Bushman, to coloured, to San, and that his earliest recollections were of his elders using the term Saa for their self-identity. The first day of the workshop also saw the group examine the various objects in the collections, discuss the memories evoked by the collections, and also examine and comment on the information generated by the museum on the objects. Their comments on the objects of spiritual significance, such as a whisk that was used during the trance dance, and the rattles that were tied around the ankles of the dancers, made from cocoons and containing tiny stones, were of particular interest. They explained how the shaman would use the whisk to sprinkle a medicine over each dancer to give them protection and strength to access the spirit world and bring healing. They also commented on the use of tortoise shells to store buchu[3] and other medicinal herbs and the potency of the tortoise shell. In addition, they commented on the bows and arrows used during a hunt. They also mentioned the blunt arrows used in courtship. A suitor would shoot the arrow at his intended partner and if she picked it up and broke it this meant she was not interested in him. If, however, she held it against her heart, this meant she accepted his overtures.

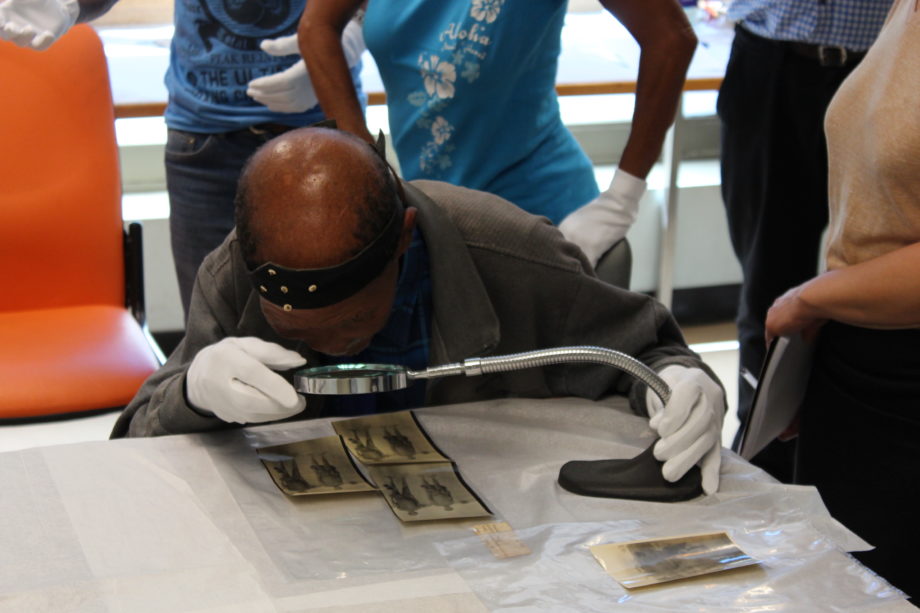

On the second day we began with a reflection of the first day’s activities. We then resumed our interaction with the object collections and the catalogue cards linked to the objects. The third day was spent on an examination of, and discussion on, the photographic collections relating to the Khomani San. During the examination of the photographs, the group, in a moment of excitement, began to communicate with each other in Nxu and we had to request that they translate the interaction in Afrikaans. In the Bleek and Lloyd photographic collection, the group were able to identify relatives and community members they had known. Lydia Kruiper identified her father, brothers and other community members, who had been photographed during a healing ceremony, as well as during hunts. She was able to provide background information on her family and other community members. Petrus Vaalbooi identified his mother, Elsie Vaalbooi, who had been a fluent Nxu speaker and a member of the Khomani San Council of Elders. She passed away in 2002. Petrus and his mother had been involved in an initiative to trace surviving Nxu speakers in the Northern Cape. Curiously, Petrus Vaalbooi commented that, contrary to the images projected of the San, his grandfather rode a horse, hunted with a gun, and was a sheep farmer.

The fourth day was dedicated to a visit to the Iziko South African Museum where the group did a walk-through of the Rock Art Gallery and reflected on the messages associated with the different rock art paintings. They also visited the Mammal Gallery and the Discovery Room. As Petrus Vaalbooi had expressed an interest in assisting the Iziko Museums with resolving the question of the restitution of human remains, we held a meeting with the Executive Director of Core Functions to discuss possible areas of collaboration. The group offered to speak to other groups, including the Khoi-Boesman-Nguni-Coali- tion, to encourage everyone to come to the table in the interest of reburying the human remains as they found it deeply disturbing to think of their ancestors lying in boxes in museums. They also suggested that the San Council be involved in deliberations as they are, ostensibly, tasked with representing the interests of all San groups in South Africa.

The final day was spent on an oral history interview with the group, followed by a discussion on how to proceed. We had been considering how we could broaden such an exercise to include other San groups, as well as Khoi groups. Interestingly, this was also an issue that was raised by the Khomani San group. We considered how the issues discussed during the workshop could be taken back to the broader community in the Kalahari, given the challenges of distance – one thousand and seventy-nine kilometres to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park to Cape Town. We provided the group with images of the object collections and copies of the photographic collections and also wrote up a report, which was sent to the San Council so that the community could receive some feedback from the museum. Other factors to consider were the lack of electricity and the high rate of illiteracy within the community.

We are hoping to build on this exploratory project and, together with the Khomani group, reach out to other Khoisan groups so as to open the museum collections to communities and bring community narratives to these collections. One of our concerns is that while museums focus on the past history of the Khoi and San, there is little focus on the resurgence of San and Khoi identity and on how the past speaks to the present. There is a sense of frustration amongst the indigenous communities, as museums are perceived to have neglected their histories. There is little or no contemporary collecting taking place around the material culture of the San and Khoi descendants. There is also a need for a dynamic oral history project that can trace the narratives that have been handed down through the generations.

In attempting to rewrite the museum archives we must consider not only the language and content of the archives but also the collections that raise ethical questions. For example, we know of at least one artefact, a skin bag, that was in the ownership of one of the San prisoners used in the Ethnographic Gallery casting project. Given the violence and racism that were an integral part of the making of the San casts in the exhibition diorama, how should such artefact be treated? This also raises the question of how much research has been conducted into how the collections were acquired. We need to research all collectors who sold or donated collections to the museums in order to try and understand how these items may have been acquired. Vibeke Viestad’s study makes mention of »photographs of naked people taken by Dorothea Bleek« in the South African Museum collections, though she adds that »these have of course never been published online unlike her other field photographs« (Viestad 2014: 40). What are the rights of descendant communities when faced with photographs that violate their ancestors? As a collections department tasked with the digitizing and care of the collections, we realise that the rewriting of the museum archives is an enormous task, which calls for partnerships that can provide valuable research assistance. In order to truly integrate the social history collections, we need to rewrite the documentation on the objects while also acknowledging the flawed interpretations stemming from the periods of colonialism and apartheid. We should be working towards an inclusive museums archive, which recognizes the multiplicity of voices and histories of people as they crossed paths with history, and which also critically addresses the violence and racism underlying the narratives linked to our ›ethnographic collections‹. The lesson from the Miscast exhibition is that if we do not involve communities in these endeavours, our knowledge production systems will remain flawed.

Fig. 1: The Ethnographic Gallery at the Iziko South African Museum declared a ›colonial crime scene‹. Photo: Wandile Kasibe, Iziko Museums.

Fig. 2: Petrus Vaalbooi, Traditional Leader of the Khomani Bushman/San examines photographs at the Iziko Social History Centre. Photo: Janene van Wyk, Iziko Museums.

Fig. 3: From left to right: Anna Marie Vallbooi, Lydia Kruiper and Iziko staff member, Marie Scheepers, examining photographs from the Bushman/San collection at the Iziko Social History Centre. Photo: Janene van Wyk, Iziko Museums.

Fig. 4: Isak Kruiper (in white cap), Anna Marie vaalbooi, Lydia Kruiper and Petrus Vaalbooi examining bags and a coat fashioned from animal skin, Iziko Social History Centre. Photo: Janene van Wyk, Iziko Museums.

Fig. 5: Isak Kruiper and Petrus Vaalbooi inspecting Bushman/San arrows at the Iziko Social History Centre. Photo: Janene van Wyk, Iziko Museums.

This article has undergone a double-blind peer-review.

The print version of this text is published in the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, issue “The Post/Colonial Museum”, 2022, p 47-59. In order to make the issue “The Post/Colonial Museum” available to a wide readership, specifically on the African continent, we decided to use the long standing collaboration between boasblogs and the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften to successively publish all contributions in print and online (as DCNtR debate). We thank the editorial boards of both, the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften and the boasblogs, as much as the publishing house transcript for embarking on this project together. Furthermore, our thanks go to the participants of the conference on Museum Collections in Motion, which was generously supported by the Global South Studies Center, University of Cologne, the research platform “Worlds of Contradictions”, University of Bremen, the Museumsgesellschaft of the Rautenstrauch- Joest- Museum and the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Most of all, we thank the contributors to this debate for four years of exchange, debate and intellectual companionship.

Footnotes

[1]The human remains collection at the Iziko Museums also includes remains from Namibia, Botswana and Australia.

[2]Some indigenous communities prefer to be identified as ›Bushman‹ rather than ›San‹. A number of researchers have commented on the fact that both of these terms are problematic, having been thrust on communities, and that some indigenous communities prefer to ›self-identify‹.

[3]Buchu is an aromatic fynbos herb with healing properties. It was used for centuries by the indigenous peoples of the Cape in various rituals and as a medicine.

References

Art Africa (2018): »Curating the Colonial Crime Scene: Heritage & Violence of Ethnographic Racism«, https://artafricamagazine.org/curating-colonial-crime-scene/ (30.06.2021).

Bodenham, Hugo (2017): »Light in the Darkness«. In: Exhibition proposal submitted to Iziko, 3 November 2017.

Smith, Andrew (2017): »It was a Grave Mistake to Have Got Rid of the Diorama at the SA Museum«, Cape Times, 16. August 2017, 9.

Coombes, Annie (2003): History after Apartheid: Visual Culture and Public Memory in a Democratic South Africa, Durham: Duke University Press.

Davison, Patricia (1998): »Museums and the Reshaping of Memory«. In: Negotiating the Past: The Making of Memory in South Africa, ed. by Sarah Nuttall/Carli Coetzee, Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 113–160.

Dubin, Steven (2009): Mounting Queen Victoria: Curating Cultural Change, Auckland Park: Jacana Media.

Gibson, Laura (2019): Decolonising South African Museums in a Digital Age: Re-Imagining the Iziko Museum’s Natal Nguni Catalogue and Collection, PhD Thesis: Department of Digital Humanities, London: King’s College.

Gore, J.M. (2004): »A Lack of Nation? The Evolution of History in South African Museums c.1825–1945«. In: South African Historical Journal 51, 24–46.

Leggasick, Martin/Rassool, Ciraj (2000): Skeletons in the Cupboard: South African Museums and the Trade in Human Remains 1907–1917, Cape Town: South African Museum.

Mandela, Nelson (1997): Address by President Mandela on Heritage Day, 24 Septem- ber 1997, http://www.mandela.gov.za/mandela_speeches/1997/970924_heritage.htm (30.06.2021).

Maykuth (1996): »Colsberg Remains«. In: Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 June 1996.

Mbembe, Achille (2002): »The power of the archive and its limits«. In: Refiguring the Archive, ed. by. Carolyn Hamilton/Verne Harris/Jane Taylor et al., Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 19–26.

Morris, Michael (1996): »Baring the True Culture of Bushmen: The National Gallery Ex-hibition Offers a Fresh Approach to History«. In: Miscast – Centre for Curating the Ar- chive – University of Cape Town, http://www.cca.uct.ac.za/cca/projects/miscast-archive (30.06.2021)

Peckmann, Tanya (2003): »Possible Relationship between Porotic Hyperostosis and Smallpox Infections in Nineteenth Century Populations in the Northern Frontier, South Africa«. In: World Archaeology 35: 2, 289–305.

Evans, Jenny (2017): »We Want Bones of Our Ancestors Back from Europe, says Khoi Chief«, news24, 10. March 2017, https://www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/ News/we-want-bones-of-our-ancestors-back-from-europe-says-khoi-chief-20170310 (01.07.21).

Rassool, Ciraj (2015): »Re-Storing the Skeletons of Empire: Return, Reburial and Rehumanisation in South Africa«. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 41: 3, 653–670.

Rogoff, Irit (2002): »Hit and Run – Museums and Cultural Difference«. In: Art Journal 61: 3, 63–73

Sunday Independent (1996): »As Museumgoers Literally Walk all Over the Brutal Fate of the Bushmen, They Seem to Miss the Point«. In: The Sunday Culture/Sunday Independent, 26. May 1996.

Viestad, Vibeke M. (2018): Dress as Social Relations: An Interpretation of Bushmen Dress, Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Wanless, Ann (2007): The Silence of Colonial Melancholy. PhD Thesis, Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand, http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/5710 (12.04.2021).

Witz, Leslie (2012): »Making Museums as Heritage in Post-Apartheid South Africa«. Göteborg: International Journal of Heritage Studies/Heritage Seminar at University of Gothenburg.

Witz, Leslie/Minkley, Gary/Rassool, Ciraj (1999): The Castle, the Gallery and the Sanatorium: Curating a South African Nation in the Museum, Kimberley: McGregor Museum.

Lynn Abrahams is the Chief Curator of Social History & Art at the Iziko Museums of South Africa.

Paul Tichmann is a doctoral student in the History department at the University of Western Cape He is the Director of the Collections and Digitisation department at the Iziko Museums of South Africa and was formerly the curator of the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum in Cape Town. His areas of focus include labour history, slave history and South African history.He has worked in the museums sector for twenty years. His employment history includes working as a Researcher at the University of Durban-Westville’s Institute for Social and Economic Research and as a Course Writer and Educator in the Labour and Community Resources Project of the South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) Trust.He has an MA Degree in Economic History from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa.