Artistic Interventions in the Historical Remembering of Cape Slavery, c.1800s.

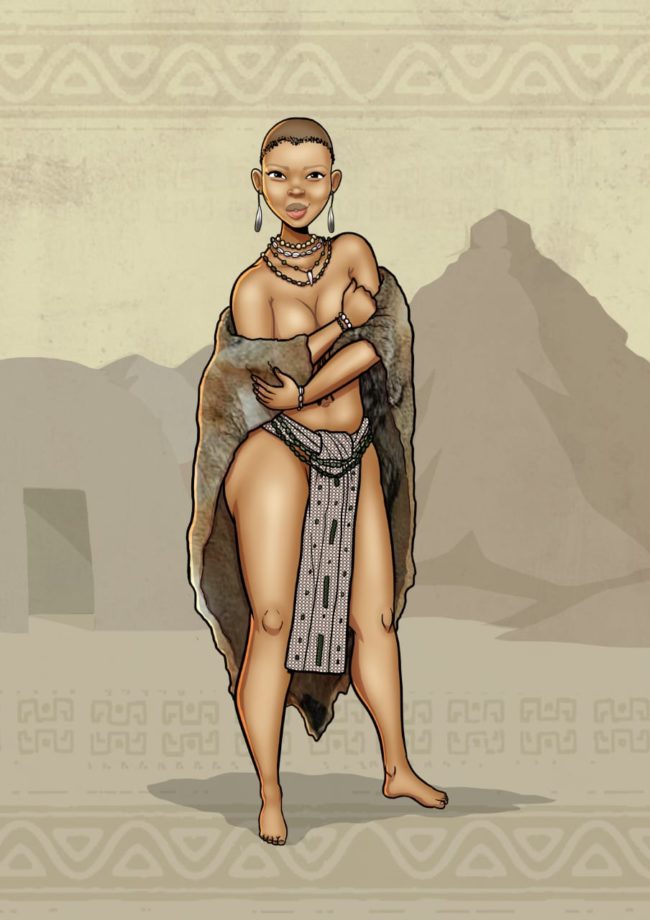

Kakapusa © Dav Andrew.

Traces of Violence from Dismembered Archives

In recent years, there has been an outpouring of critical scholarship focused on dissecting colonial museums and archives, specifically in relation to the difficulties of retrieving the voices of black indigenous enslaved women in ethnographic collections.

Frequently, historians note that traditional archival material is incomplete and written primarily by powered functionaries or dominant groups. However, there remains a paucity of scholarship that looks at archives of slavery in the Cape to challenge the meanings within silences and erasures; to be explicit about the archival limits and understand that these limits hold power that potentially make absent multiple possibilities in narrating indigenous black women’s lives. An acknowledgement of these limits is not an alternative mode, but instead a proposition to understand absence and fragments contained in archives differently, to re-think the empty spaces where enslaved and indigenous women are erased.

Entering archive(s) of slavery there is a need to consider meanings within the absences, erasures and silences. I am at pains with the violence of the archives and subsequent writing productions of histories that reproduces violence, evoking the unbearable and unspeakable through “simplified, quantified and seemingly objective account[s]”[1] Reading and facing the laments of archival silences to excavate gendered enslaved narratives whilst trying to make sense of it all, I am at pains with the difficulty of retrieving the voice of enslaved women from these colonial depositories.

Being wedged in a constitutional disciplinary thinking[2] and making sense of these archival silences whilst trying to express it in a grammar of language that conveys this is constrained by a disciplined thinking. Conventional methodologies, embedded with particular ideological positions, denies the plurality of historical writing and chokeholds the analytical power in various structures of language and meaning-making.

Narrating archival fragments requires exceeding the confinements of the archive as it has been traditionally thought to historians, to interrogate the limits of the archive not within a footnote but as a subject of study itself. It matters in how historical events, moments and representations are (re)produced and in so illuminating scripted violent reproductions of colonialism.

Indigenous black and enslaved women, in the colonial archive, including the 19th century Cape archive, are already projected through the realm of sexual violability and colonial desire.[3] Saidiya Hartman, in challenging the constraints, evokes imagery to write a narrative of gestures that relay archival refusal. Alluding to a spectrum of speculation in Venus in Two Acts, Hartman asks,

“is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive? [4]

For Hartman, storytelling involves critical speculations about the gaps and silences of officially curated archival records and thinks through the subjunctive to open narratives that are within conditions of absence and erasure. Fleshing out the historian’s relation to the archive, in this case, is paradoxical: exposing one to both a site of possibility and impossibility.[5]

The paucity and evasiveness of historical documentation on lives of enslaved women in South Africa, usually provided in court records, slave sales and passing records, requires innovative ways of looking at slave and indigenous women’s presences in history.[6] Pumla Gqola argues that feminist imperatives require an examination of “unconventional” locations that “function as valuable sources of contestatory meanings,”[7] urging historians to interrogate the notion that traditional archives are the only repository of valuable knowledge.[8]

It is only through awareness of limitations of archives that a nuanced understanding of slave and indigenous women can occur.

Archival Refusal: Traces of Sacred Memory

Living in sacred memory, overcrowded metropolitan cities surrounded by colonial imperial visions- spatially, architecturally. Peeking through Huri ǂoaxa, wedged in the sacred places of human memory and oral testimony, ||Hui !Gaeb. Erratic spirits of Abo Abogan, not easily stuffed and closeted in towered buildings of colonial aesthetics. Secured for imperial desires- and antipathies so deep and enmeshed in neoliberal humanism- for so humanist the hundred and thousands of Khoi Warriors were murdered to prove ownership. Decades and centuries later – private ownership or “you’ll be prosecuted” – our struggles-private ownership: the skies, beaches, the soil. “Water overflows with memory. Emotional Memory. Bodily Memory. Sacred Memory.”[9]

The questions I broadly mediate on are: what do artistic archives such as storytelling and sacred knowledge have to offer for the narrating of history in museums? When chronology is disrupted through evasiveness/absences/silences, what negotiations are made to construct a historical discourse? What is the potential or foci of critical and reflexive methods and how are these experiences analysed? To think through these contradictions and paradoxes as productive tensions enable the possibilities of plausible courses of action in (re)membering colonialism and slavery.

In meditating on memory, in context situ sacred memory, it is a vast and expansive terrain that refuses the material archival positionality. It is not tied to the limits of earthly time, enclosed in colonial maps or positions, not dependent on the corporeal body, instead it moves in-between spaces of mind-body-soul, refusing to be “imprisoned as exhibit in a museum or archive.”[10]

“The dead do not like to be forgotten, especially those whose lives had come to a violent end and had been stacked sometimes ten high in a set of mass graves…”[11]

A spiritual encounter, Alexander reflects, is a “dangerous memory,” traces of Abo Abogan (ancestors) lives, dreams, shadows or hauntings, vibrations of feelings, a reflection which may even come through intersectional manifestations.[12] In order for the Spirit to come into being, they require embodied beings, manifested in the quotidian. Therefore, it goes without saying that legal and missionary records only give us proximate access into the daily living experiences. They are unable to convey the intimacies of the interior lived experiences which cannot be expressed in colonial ways of recording-remembering.

This draws parallels to the idea of archival refusal, a refusal of the Spirit to be consigned in categorical records, defined by state corpus and colonialists or me as a History student. The Spirit moves through multiple mediums and possesses the power of refusal into submission and being captured. What if the histories we are telling is an archival refusal? What negotiations are made to highlight this, or do we remain epistemologically deaf to the impasse?

In the spirit of praxis, of doing the work, Alexander as a historian explains the utilisation of sacred memory, the memory of ancestors, as a channel to expressing the textures of their lives, beyond the confines of captivity narratives contained within colonial/traditional archives. At what point do we face the reality that the formal conceptualisation of archives through jurisprudence lenses are used as western hegemonic disciplinary mechanisms?

Constructing with radical vulnerability

When academic truths gain their rigor through conceptual and methodological disciplining and reductionism, it is easy to declare such truths universally replicable and verifiable. The wild, complex, irreducible contexts of lives, struggles, and relationships are often treated as irrelevant or actively shoved into the background in the process of producing such truth claims.[13]

An inquiry into feminist methodology engaging the gendered collections of Iziko Museum, former Slave Lodge, poses critical questions related to the authority of research using paradigms and classifications of western constructions to speak to gender, sexuality, class and race. These collections hold multiple stories, languages and silences, beckoning us to question and grapple with how to write against power relations in ethnographic collections that enact and transcribe violence in knowledge/writing production?[14]

The praxis of radical vulnerability returns to question of ethics related to “how and why one comes to a story and to its variable (re)tellings.”[15] The act of storytelling has a pedagogical and methodological intent that “confront ways in which power circulates and constructs the relationalities within and across various social groups,”[16] asserting unavoidable gaps/silences that emerge. However, embracing radical vulnerability as “mode of being” invokes ethical and methodological encounters to recognise that academic knowledge is enrichened through creative dialogue with artists and activists.[17] Collaboration(s) with artists and activists in archival praxis play an important role in the intergenerative dialogues across social and institutional borders.

Conversations and sharing stories become an opening for collaborative praxis, authoring from multiple locations to negotiate marginalised representation and depletions of violent renderings that read women as absent subjects. Decentering authorial voice recognises that a plurality of being means kindling the politics of building horizontal comradeship, sharing visions of liberation, dreams and learning together. This process, Richa Nagar and Koni Benson echoes are “co-determining”[18] dependent on the various aspects of research; writing productions; dialogues that do not impede on self-determined action and where conceptual worldviews may differ from academic paradigms.

In recognizing collaborative and accountable research, radical vulnerability is centralised in exploring the analytical use of co-authoring with communities. The poetics of relationality and its entanglements becomes apparent and can utilised as productive tensions in navigating knowledge productions. The purpose of situating co-authorship destabilises the grounding of a definitive and universal truth of past/present lives underpinning the importance of multiple truths as meaningful to analysing positions towards and of the communities being studied.[19]

Mischka Lewis is a ||Hui !Gaeb (Cape Town) based feminist activist and researcher currently pursuing a PhD History degree at University of Western Cape (UWC). She obtained a BA International Relations degree at Stellenbosch University (SU) and Honours in Historical Studies at University of Cape Town. Mischka’s research looks at the herstory of violence against indigenous and black women in the Cape Colony during the first half of the nineteenth century (1806-1834). The difficulty of retrieving the voice of indigenous and enslaved women from archives and museums frames her research. Mischka engages artistic interventions in the remembering of slavery and colonization, specifically looking at themes related to gender, black radical feminist theory and performativity, African spirituality, sexuality and violence.

About the DCNtR Debate #1: It has long been accepted that colonialism had a distinctive epistemic dimension, which was upheld by disciplines such as social anthropology and other knowledge-making projects. Under this colonial episteme, people and human experiences were hierarchically classified according to racial categories and ethnography and ethnographic collecting were key components in these processes. However, the colonial regime did not only rely on race as an organising category, but also on gender. The first debate in the DCNtR Debates series tackles this question with seven contributions from around the world which explore the relationship between the gender of the collector, the gender of those collected from and consequences of these gendered practices of collecting for the epistemic practices of display in today’s museums.

Footnotes

[1] Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts, “Small Axe 12, 2 (2008):2.

[2] In reference to the traditional Historical disciplinary thinking that considers colonial archival evidence to be legitimate.

[3] Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford University Press, 1997), 11-12.

[4] Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, 2 (2008),2

[5] Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 2-3.

[6] Pumla Gqola, “Like three tongues in one mouth,” Women in South African History, ed Nomboniso Gasa (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2007), 37. Also see P. Gqola, What is Slavery to me? (Johannesburg, Wits University Press), 1-7.

[7] Gqola, “Like three tongues in one mouth,” 32. Gabeba Baderoon’s Malay cooking as an alternative archive encodes meanings of Malay traditions and enslaved women is one such example.

[8] Ibid 36- 38.

[9] Ritual inspired by quotation from Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred, Perverse Modernities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005),318.

[10] Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing, 314. Alexander’s arguments raised questions for me around how one embodies rituals in written form? And what negotiations are made in terms of the performativity and meanings produced? Dreams, sacred practices, spiritual manifestations are not constituted as a historical study, yet indigenous black histories are informed by the connection of mind-body-soul in contrast to the western Kantian models of scientific enquiry through mind-body binaries.

[11] Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing, 317.

[12] Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing, 337. Intersectional manifestations signifies Spirit ability to inhabit vast planes of consciousness.

[13] Nagar, Muddying waters, 175.

[14] Richa Nagar, Muddying waters: co-authoring feminisms across scholarship and activism, Dissident Feminisms. (Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 21.

[15] Ibid, 14.

[16] Nagar, Muddying waters, 14.

[17] Ibid, 15.

[18] Koni Benson and Richa Nagar, “Collaboration as Resistance? Reconsidering the Processes, Products, and Possibilities of Feminist Oral History and Ethnography,” Gender, Place & Culture 13, no. 5 (October 2006): 584.

[19] Benson and Nagar, “Collaboration as Resistance?,” 583.

References

Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred. London: Duke University Press, 2005.

Katherine Fobear. “Do You Understand? Unsettling Interpretative Authority in Feminist Oral History,” 10, 2016.

Koni Benson and Richa Nagar, “Collaboration as Resistance? Reconsidering the Process, Products and Possibilities of Feminist Oral History and Ethnography.” Gender, Place & Culture 13, 5, 2016.

Pumla Gqola, ‘Like three tongues in one mouth’: Tracing the elusive lives of slave women in South Africa,” in Basus’iimbokodo, bawel’imilambo/ They remove boulders and cross rivers: Women in South African History, ed Nomboniso Gasa ,Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2007.

Pumla Gqola, What is Slavery to me? Johannesburg, Wits University Press, 2010.

Richa Nagar, Muddying waters: co-authoring feminisms across scholarship and activism, Dissident Feminisms. Urbana, Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts, “Small Axe 12, 2, 2008.

Saidiya Hartman, Lose your Mother: A journey along the Atlantic Slave Route, New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2008.

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-century America , New York: Oxford University Press.