(Counter)public Contestations:

Feminist Theorizing for Anthropological Ethics

Feminist theorizing – particularly contributions from beyond the Global North – has always been marginalized in anthropology although it has successfully challenged hegemonic knowledge production as well as unjust economic systems and political hierarchies based upon patriarchal gender ideologies for a long time. In the context of our discipline, this resulted in feminist anthropologists’ contestations of male-biased ethnographies, and Black feminist anthropologists’ contestations of the marginalization of non-white women* scholars’ academic work. A recent example of that, published in Feminist Anthropology, is the demand to cite Black women by way of a critical praxis in order “to begin overturning the patriarchal, heterosexist, imperialist, white supremacist structure of anthropology” (Smith and Garrett-Scott 2021: 32).

If one looks ‘outside the house of anthropology’, feminism seems to have experienced a renaissance as well. In contexts like the international development sector or civil society, feminist activist groups appear to thrive more than ever and, despite critical voices from within these movements, they are frequently presented in a homogenous manner. A different dimension of feminist initiatives, narratives, and discourses becomes visible if we consider the oppositions and refusals they face. Alongside enthusiastic support, feminist positions and practices are met with diverse negative reactions from critique to ridicule and, sometimes, outright rejection in public, (semi)public, and private spaces. As much as a feminist revival, we are also witnessing a globally emerging backlash against feminist politics. These are spearheaded, for example, by well networked groups of masculinists who equate feminism with women’s empowerment happening at the expense of men. From Kenyan adherents of the so-called Red Pill ideology to Indian MGTOW (“men who go their own way”) and right-wing masculinists who embark on terrorist attacks worldwide, feminism and the knowledge it has produced, are under attack on many fronts.

In this short reflection, we suggest to think productively about the fact that feminism is increasingly challenged as a hegemonic knowledge system operating in and through privileged institutional spaces of the Global North. We intend this not as a defense of a specific type of feminist theorizing, be it liberal, radical, or Marxist, but suggest that thinking with critiques of and refusals to feminism can inform the anthropological ethics we navigate our practice by. A point of departure for this discussion is the inevitable global plurality of how feminism is imagined and lived and the urgent necessity for including not only the perspectives of those who identify with it, but also of those who contest it, be they young Kenyan men who feel sidelined by the international aid community or Tanzanian gender justice activists who are hesitant towards an increasing financialization of development cooperation initiatives branded as ‘feminist’. Such an engagement with how men and women navigate and contest feminisms allows for a critical perspective on Western neoliberal feminist practices that frequently focus solely on economic empowerment and are spread by international NGOs worldwide, which has resulted in shifting the focus “from the transformation of socio-economic life towards securing women’s equality in the pre-existing structures of capitalism” (Srinivasan 2021: 163).

Feminism as Traveling Theory?

An important observation to keep in mind as feminist theory and queer theory continue to grow apart in disciplinary terms but overlap and intersect in many of their epistemological and political goals, is the fact that while feminist narratives have become a dominant norm in many Southern setting, queer narratives have not. Quite the opposite, the queer community currently experiences some of the harshest attacks in a long while and across various African settings. However, while local actors and often high-ranking politicians try to prevent queer theory and the LGBTQ community from gaining ground in what are presented, through culturalist arguments, as ‘traditional’, i.e. heteronormative, African societies, feminism is increasingly attacked not because it challenges hegemonic ideology, but because it has come to be viewed as being central to the narratives and strategies of legitimization of powerful political actors. Put differently, while feminist theory continues to be a tool of contestation within the house of anthropology, it has often been coopted by neoliberal forces outside of that house. In East African settings, such as Tanzania, for instance, feminist trust funds are presented as the “only funding support mechanism” whereby actors try to use their financial, distributional, and political power to decide upon what counts as feminist and what does not. In such contexts, feminism increasingly becomes contested because it is understood to be part of an oppressive political system, and we believe that such contestations of feminist thought and practice hold critical relevance for anthropological ethics itself.

Unlike in queer theory, “feminist anthropology is still too often seen as pertinent only to gender or to cis-women’s lives” (Mahmud 2021: 346) which tends to limit the scope of feminist anthropological questions from including those critical social problems of our times, often caused by global capitalism, that lie outside of normative notions of gender and womanhood. We therefore take up Mahmud’s outline of the question, how what we ask and do in anthropology may be inspired by feminism without limiting itself to the concerns of women and gender, but instead to become “a refuge for a capacious field of gender and sexuality studies and for traveling theories of bodies and power” (2021: 355). By thinking beyond the US-centric context of Mahmud’s argument, we emphasize the need to decenter who and what informs feminist theory, and to connect this question about the makings of theory with a reconsideration of the ethics of anthropology. If theorizing means “to make an argument, to make sense of the world, to name and create” (McGranahan 2022), then taking seriously our interlocutors’ (anti)feminist arguing, sense-making, naming and creating may also reconfigure a more general ethical questions of anthropological practice and knowledge production.

Where Feminism is in Question

Kenya

“It is time to take charge and refuse to be bullied into destructive surrender and unchecked capitulation to the failed feminist experiment […]. It is time for men to rediscover the operant masculine frame needed to steer society towards order.” In his work on the anti-feminist backlash in Kenya, Schmidt came across this statement in a Kenyan Telegram channel, which combines militant masculinity, self-help, and conspiracy theory. The channel is organized by Amerix, a medical practitioner from Western Kenya who has become one of East Africa’s most successful social media personalities. While over one million users follow Amerix on Twitter, his Telegram channel counts over 100,000 members from across East Africa, Nigeria and other countries, though the vast majority are Kenyan. While one might feel that his dietary advice, sexual education, explicit anti-feminism, misogyny, and celebration of political dictators, such as Rwanda’s Paul Kagame or Russia’s Vladimir Putin, would only appeal to a minority of already radicalized Kenyan anti-feminists, it would be short-sighted to consider Amerix a niche phenomenon or eccentric oddball. Quite the opposite, he has become the voice of both poor and disadvantaged as well as privileged and wealthy Kenyan men who increasingly attribute their perceived loss of patriarchal control to the threats of feminism.

Mark Odhiambo, a 27-year-old migrant from western Kenya and unemployed university graduate living in Nairobi, is a case in point. After graduating with a degree in Physics, he struggled to find permanent employment and stayed afloat by writing essays for Chinese students. Dissatisfied with his economic status and romantic life, he repeatedly described Kenyan women to Schmidt as materialistic and unfaithful, thereby vilifying and making them responsible for his current problems: “Women are women. They are always materialistic. […] When she needs something and there is somebody giving her a better option, she will go for it.” When Schmidt asked Mark about Amerix, he got excited and claimed that the advice of Amerix had been “educative” for him since he had first read his Twitter posts:

Amerix is talking about why shouldn’t we be us? Why do you have to be dictated by a woman? Let the woman decide whatever you have to do. Be away from friends, she does not want that. Do whatever she wants? You see that? So, we were like, give us this shit. […] From the first day, we were all into this Amerix thing. […] there are some people who argue that Amerix is misleading the men, but then if you understand what Amerix is talking about, it is the real thing, the real situation on the ground.

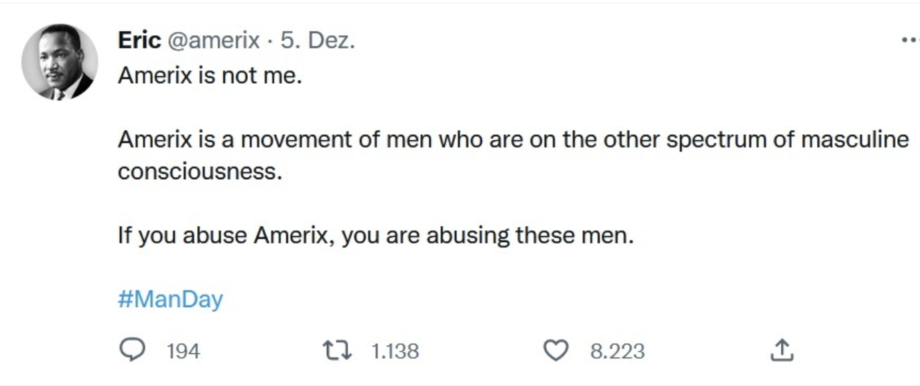

Screenshot of a Tweet by Amerix, exemplifying the political component of his antifeminist stance. Source: Amerix’ Twitter account.

The fact that close to one million Kenyans, such as Mark, follow a man who equates feminism with a deliberate attempt to harm or attack men raises a few interesting questions: What can we learn about the state of gender relations in Kenya if many Kenyan men feel understood and represented by Amerix’ anti-feminist, anti-democratic, and pseudo-scientific advice? What does it say about feminism as a progressive social movement if it fails to convince Kenyan men of the fact that they would also benefit from overcoming patriarchal notions that peg men’s value to their economic performance? And, probably most importantly, what is the value of feminist practice if it does not manage to overcome capitalist notions of the economy as a zero-sum game in which the profits of one party are the losses of the other?

Tanzania

“Congratulations” – A banner in Zanzibar’s Michenzani neighbourhood in celebration of Samia Suluhu Hassan becoming president of the United Republic of Tanzania in March 2021. Copyright: Franziska Fay, August 2021.

In Tanzania, the recent change of political power which moved the current female political leader into the presidential seat of the country has generally led to an increase of discussions on the compatibility of political power, womanhood and feminist values (see, for example, Khalifa Said’s discussion “Tanzania has a female president. Does it have a feminist president?”). In the context of such debates, particular emphasis has been put on the relevance of class difference at the intersection of ‘feminist’ demands and discourses. One important orientation can be found in the declaration by the Manzese Working Women’s Cooperative (UWAWAMA, Ushirika wa Wanawake Wavujajasho Manzese) (Swahili original; English translation) that stresses how different class realities impact and shape working women’s realities and demands in Tanzania.

During an alternative gathering to celebrate International Women’s Day on 8 March 2022 that aimed to make this celebration more inclusive by, for instance, addressing “working women” specifically – including small business operators and smallholder farmers who continue to be pushed to the margins of mainstream feminist forums – the Manzese Working Women’s Cooperative formulated “six abiding demands for working women” (translated by Michaela Collord). By way of these demands the women of the cooperative made clear that “as women who face a variety of challenges under all oppressive systems, we realize that our interests are different from the interests of upper-class women (Tukiwa kama wanawake tunaokumbana na madhila mbalimbali chini ya mifumo yote kandamizi, tunatambua kuwa maslahi yetu ni tofauti na maslahi ya wanawake wa tabaka la juu)”:

- Full economic freedom

- Freedom to own land and protection from land-grabbing

- Free social services

- The right to the city for all, without discrimination

- Decent jobs for all

- An end to gender-based violence in all its forms

It is this internal differentiation and critique of the equation of the demands of upper-class women (wanawake wa tabaka la juu) with the demands of Tanzanian women more generally, and the key demands of “full economic freedom”, “ownership of land”, and “access to services” that should guide our ethnographic attention. These political demands for social equality and justice resonate with Tanzanian pan-African feminist activist Mwanahamisi Singano’s critique, who made clear in a conversation with feminist scholar Rama Salla Dieng, that a particular frustration with the changing landscape for feminist activists in East Africa lies in a “political and ideological bankruptcy among activists or even those who identify themselves as feminists”. Singano reminds us that “ideology glues and shapes movements” and “sets parameters of what is negotiable and non-negotiable” for feminist activists. Shying away from positioning oneself is thus dangerous as it might result in “congregations in the name of movements […] being institutionalized to become the properties and entities owned by a few who work every day to become ‘donor darlings’ at the expense of others.”

Taking seriously the political positionalities that frequently lie outside of majorly funded international development-linked feminist initiatives can prevent reinscribing reductionist notions of what feminist practice may look or work like. This could contribute to deeper understandings of the complexity of feminist movements that is often simplified and misrepresented when the diverse and critical voices are framed as part of one homogenous ‘feminist’ movement only.

A Matter of Distribution

These insights from East Africa point out a variety of ways in which we can understand feminist theorizing more broadly by considering how both women and men negotiate gender (in)justice and engage with existing patriarchal gender relations and feminist attempts to overhaul them. If we pair the observations from Kenya with longstanding and more recent discussions on feminist questions in Tanzania, our focus is led towards socialist approaches that reiterate concerns of distribution and address questions over wealth and class with at least equal if not more pressing attention as those framed as concerning gender alone. Our conclusion further resonates with Carole Boyce Davies’ critique that emphasized that “the conjunction between left-thinking and feminism has for the most part been neglected in recent work on African women” and that “the exploration of class/gender systems as these pertain to African societies clearly needs more attention” (2014: 86).

In Kenya, the backlash that is particularly visible in anti-feminist “digital counterpublics” (Okech 2021) is framed as a fight of all men against a culturally imposed ‘femicentric’ world order. This obscures economic differences between men which the antifeminist backlash justifies by pointing out wealthy men’s supposedly more masculine biology and practices. What is presented as a form of male liberation movement, in other words, helps to solidify political-economic hierarchies between men as well. It would make little sense to blame liberal feminist narratives for the emergence of the Kenyan anti-feminist movement. However, we do believe that neoliberal feminism’s failure to integrate socialist demands for the establishment of an economically more just society into its program has helped to, on the one hand, turn feminism into the ideological bootstrap of upper-class women who are economically empowered, but ideologically blind enough to continue to exploit, for example, disadvantaged female domestic workers. The anti-feminist backlash, on the other hand, also helps to turn young and marginalized men into the ideological foot soldiers for a male elite who, now under the cover of an ideology of naturalized male supremacy, continue to make use of excessively violent and misogynistic practices to defend their class position.

In Tanzania, working women’s demands have underlined the importance of considering class inequalities in order to criticize feminist demands and requests that leave only economically more powerful and better positioned women to be heard. If feminist demands are to be successful across different contexts, they have to take general socialist aspirations, such as sufficient housing, a functioning health sector, and public education, more seriously again, and direct attention to the plight of poor women and men in the face of class oppression alike. An older generation of feminists such as Demere Kitunga and Marjorie Mbilinyi – by many considered to be among the living legacies of the Tanzanian feminist movement – should here serve as a serious point of reorientation for the feminist endeavors of the present generation. Their longstanding dedication to a socialist framework for their “Transformative Feminism” and their fight against class oppression in the context of the Tanzania Gender Networking Programme (TGNP) continues to be exemplary here.

Feminist (Socialist) Theorizing for Transformational Anthropological Ethics

What does the question of distribution that we raise mean for the ethics of our own politically informed anthropological practice? We propose that, what it may hint at, is the need to recenter the relevance of relationality and internal differentiation with regard to the people we work with and the methodological approaches we apply in the name of ethnography. Put differently, it points toward the necessity to question our own choices of who we seek out as interlocutors, who we are (consciously or unconsciously) not speaking to, and who speaks to us on behalf of other women or men with potentially insufficient representability.

In as much as an anthropology that is led by feminist demands has rightfully criticized forms of knowledge production based upon patriarchal hierarchies, a feminism inspired by the complex social realities unearthed by ethnographic fieldwork can neither speak for all women nor implicate all men to be guilty of benefiting from patriarchy. Feminist demands and feminist knowledge production are themselves often already imbued by the fact that they are articulated from specific positions of power that might contradict and suppress feminist claims made from elsewhere while most likely not being branded as coming from such specific positions. Feminist articulations that suggest a feminist anthropology may speak for all women or has the potential to bring about gender equity, therefore, might be helped by a more modest approach that recognizes the multiple positionalities of women and men alike.

“Justice has no gender” – A kanga cloth by the Tanzanian Women Lawyers Association (TAWLA). Copyright: Franziska Fay, March 2023.

An anthropological ethics informed by these insights could be inspired by an acknowledgement of the fact that all emancipatory political projects, feminist or not, depend on criticizing those who actively perpetuate political power relations and economic injustices on different scales, ranging from a small feminist meeting to a whole capitalist society. Returning to McGranahan who has argued for the need to think of “theory as ethics, rather than solely as intellectual practice” and this requiring a rethinking of “the purpose and not just the content of theory” (2022: 289), we press for a debate of how and with whom we decide to conduct research in order to understand and document what ‘feminism’ can be and do across our fields. We formulate the following suggestion that think with a fundamental socialist feminist idea of lifting others up but doing so not at the cost of others:

- Take seriously the neoliberal constraints and political-economic structures that shape how actors present “feminism” in different settings. By thus paying attention to who is allowed to speak for whom in which context, we hope to contribute to “dismantling regimes of power that are oppressing” within feminist spaces as well.

- Emphasize ‘working class’ feminist voices that remain marginalized within feminist movements in order to reimagine and realize diverse forms of solidarities in order to, for instance, emphasize the relevance of men as both opponents and allies of feminist movements.

- Become more inclusive by considering as interlocutors a broader variety of different actors and institutions. By suggesting to conduct fieldwork among those who try to stabilize as well as those who try to delegitimize feminist practices and narratives, we account for the fact that the distribution of supporters and opponents of socialist feminist demands does not neatly map unto other dichotomies, such as male-female, young-old, politically left-politically right, or poor-rich.

Because “theory as ethics operates from spaces of shared life, not just the spaces of research” (McGranahan 2022: 297), we conclude that ethnographically analyzing (anti)feminist theory as it is constituted outside the spaces of anthropology can point out less obvious or disguised political alliances as well as perpetuated injustices across feminist spaces and worlds themselves. This might allow us to reach a position from which these injustices can be addressed and potentially abolished. Ultimately, such an anthropological ethics may prevent feminism’s complicity in further supporting a neoliberal economy that has already decided which achievements will be considered feminist victories and responsibilities, and which will not.

Bibliography

Boyce Davies, Carole (2014) Pan-Africanism, Transnational Black Feminism and the Limits of Culturalist Analyses in African Gender Discourses. Feminist Africa 19: 78-93.

Mahmud, Lilith (2021) Feminism in the House of Anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology 50: 345-361.

McGranahan, Carol (2022) Theory as Ethics. American Ethnologist 49(3): 289-301.

Okech, Awino (2021) Feminist Digital Counterpublics: Challenging Femicide in Kenya and South Africa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 46(4): 1013-1033.

Smith, Christen A., Dominique Garrett‐Scott (2021) “We are Not Named”: Black Women and the Politics of Citation in Anthropology, Feminist Anthropology 2(1): 18-37.

Srinivasan, A. (2021). The Right to Sex. London: Bloomsbury.

Franziska Fay is Assistant Professor of Political Anthropology at the Institute of Anthropology and African Studies (ifeas) at Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz. Her research interests include childhood and protection, politics and gender, translation and artistic practices, feminist theories and visual ethnography in Swahili-speaking East Africa/ Indian Ocean contexts. Her book “Disputing Discipline: Child Protection, Punishment, and Piety in Zanzibar Schools” was published by Rutgers University Press in 2021.

Mario Schmidt is currently a senior fellow at the department “Anthropology of Economic Experimentation” at the Max Planck Institute of Social Anthropology in Halle/Saale where he analyzes the effects of evidence-based development aid interventions on the economic livelihoods of the inhabitants of rural western Kenya. Furthermore, he focuses on the transformation of notions of masculinity among Kenyan labor migrants in Nairobi. In this context, his book “Migrants and Masculinity in High-Rise Nairobi: The Pressure of Being a Man in an African City” will be published in 2024 (James Currey).