What’s the Use of the Archive? Questions of locality, accessibility, and digitalisation

DCNtR Debate #2. Thinking About the Archive & Provenance Research

Case 1

My (Larissa) first confrontation with issues surrounding the decolonisation and locality of archives between the Global North and South took place in 2018, through my visits to a private Nigerian archive.[1] When I boarded the airplane, I did not know of the existence of this archive yet. Once I had arrived at my destination, I was pointed towards the archive by a historian I had met at the university that was hosting me. He told me about the private and well-preserved archive of one of Nigeria’s most important historians of the twentieth century. The archive was more than one person’s collection, however, as it also served as a local center of historical research and education. Nevertheless, it was not very well known internationally. The heirs and relatives of the late historian wished for the collection to be more widely known and used, especially in a global context, but they wanted to remain in charge of the material as well. In order to secure the funding required to secure the archive for future generations and preserve its content, the owners needed to generate interest from the Global North. This was in line with the legacy they were trying to protect: in the twentieth century, the home where the archive is now located functioned as an important meeting place for historians from all over the world.

By virtue of its location and past, the archive tells an important story of twentieth century African postcolonial history. To follow Luise White in her article on ‘hodgepodge historiography’, the location of archival materials in different places and often outside of institutions reflects the chaotic nature of postcolonial state formation in Africa and is therefore a complement to its history rather than something that detracts from it .[2] To achieve greater recognition for its story, the archive was looking at funding opportunities across the world. Access matters to archives because access might help preserve the archive for future generations. However, creating greater access might decrease one’s hold over the archive’s holdings. This is also connected to the question of worth; who determines what we deem worthy enough to put in the archive? Where do we think the archive should be located to be ‘worthy’?

By using the archive, I, a white European researcher, became a part of its history of being visited by scholars from across the globe and perhaps I represented the hope that the archive could once again become a global center. As I came unannounced, I was a somewhat unexpected, but welcome user. In a way, I represented one of many threads that connected the archive to a potential greater use. My use of the archive ‘confirmed’ that it was useful to researchers from the Global North. Using an archive, then, is not an apolitical activity. Neither is it necessarily self-evident how an archive can or should be used. Archives are usually created with particular uses and users in mind. It takes effort to figure out how an archive is supposed to be used, how to make it work for you. As Sara Ahmed writes in her phenomological study On the Uses of Use (2019): ‘an archive in use is an archive that could disappear if care is not taken in using the archive’.[3]

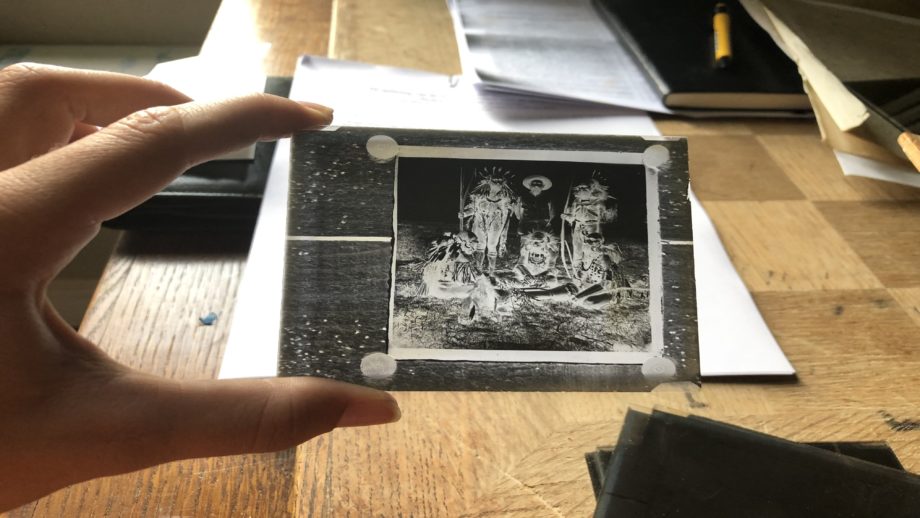

A missionary with a group of men who are part of the Marind-anim community on South Papua. Picture by the author.

Case 2:

As a researcher working with collections of colonial photography, reflection on the implications and consequences of opening and intensely engaging the colonial photographical archive is an intrinsic part of my (Marleen) research. Why did I open this archive? Why should we look at these pictures, write about these photos? By doing so, do I put people on display? Who has the right to look, to determine, to engage? These questions have been raised before.[4] Already in 1991, Mieke Bal asked: ‘doesn’t one repeat the gesture of appropriation and exploitation one seeks to criticize if one reprints as quotations the very material whose use by predecessors is subject to criticism?’[5]

Debates about the ethical responsibilities of the photographic historian in a global image economy are calling attention both to the role of photographic images and to the power relations that sustain and make possible photographic meanings.[6]

In my case, large collections of missionary photography documenting peoples and histories from all over the world (spanning the late-nineteenth and almost the entire twentieth century) are kept by a heritage centre in a small village in a rural part of the Netherlands. These are sources with great potential and potentially great emotional value, especially for communities with ‘blank pages in their family albums’.[7]

How can these collections be made available globally?

Anthropological research in Oceania has been leading in terms of considering present meanings of historical photographs, tracing the various uses and connotations of photography through time and space, considering the meaning of colonial photography for the descendants of the communities depicted in the photographs. A relatively recent development is the visual repatriation of colonial photographs, making scattered photographic collections in museums and archives (digitally or physically) available to host communities worldwide.[8]

Although large scale digitalisation may improve equal access and allows for different perspectives to emerge, it is not without risks. Loss of context is one risk. People depicted in colonial imagery are – once again – subjected to the inquiring gaze of strangers halfway across the world. As they cannot be asked for their permission in this matter, it is important to wonder whether our gaze is legitimised. Issues of privacy and ownership remain pertinent. Who owns or controls access to historical images – and, consequently, to some of the chief ingredients of history – has become an urgent, weighty issue, even more so due to the commercialisation and privatisation of digital archives.[9]

Concluding Thoughts

The classical concept of the archive is to deposit, to label, to tuck away ‘safely’ with the archivist as gatekeeper, to be taken out only for approved uses: exhibition in the museum, examination by researchers, restoration by the curator. This classical idea of the archive may not take into consideration the myriad of ways in which archives are living things, intimately connected to their communities. By using the archive in the ‘classical’ way we might reinforce pre-existing power structures that primarily benefit the Global North, or repeat imperial narratives and ideas. In her recent work Potential History, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay discusses the ‘violence involved in the implementation of practices and procedures such as collecting, classifying, studying, cataloguing, and indexing and on the institutionalization of these practices as neutral with respect to their objects’.[10]

If we take the two collections described above as a starting points, we might wonder what it means to “share” the archive, to create greater, global access. Greater access in the first case is connected to greater worth which is in itself connected to the location of the archive. It is its location in the Global South which makes it less accessible to researchers in the Global North. Where worth is located, to again follow Ahmed, is important in this story.[11] Location, moreover, is intimately connected to the histories of the postcolonial, as White has noted in her article.[12]

For postcolonial histories of the Global South her ‘hodgepodge historiography’ means working with the bricolage of history as it has become literally deposited in various corners of the world.[13]

Yet, as the second case , concerning the visual archive, digitalisation or repatriation of colonial archives might not be the answer to this dilemma, as it brings with it other questions and risks of ownership, exposure, decontextualisation. To conclude, we want to ask how we can complicate our understanding of how we, as researchers from the Global North, make use of the archive. Is it possible to use the archive in such a way that it becomes a truly shared, democratised space?

Larissa Schulte Nordholt is a lecturer at Leiden University and has recently finished her PhD at the same university. Her PhD research concerned the UNESCO-funded General History of Africa/l’Histoire Générale de l’Afrique (1964-1998). In her dissertation she has analyzed how the UNESCO project aimed to decolonize the writing of African history and what that looked like in practice. She is interested in questions of historiographical decolonization and emancipation in the broadest sense, including in its historiographical practice in archives and through citational politics.

Marleen Reichgelt is a PhD candidate at the History Department of the Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Her research project (2017-2022) is centred around missionary photography, which she uses to study the position, agency, and lives of children engaged in the Catholic mission on Netherlands New Guinea between 1905 and 1940. In addition to her PhD project, Marleen works as an archivist at the Heritage Centre for Dutch Monastery Life and as editor with the Yearbook of Women’s History. She has published on missionary photography and colonial childhoods in BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review (2020) and Trajecta (2018).

Footnotes:

[1] We have chosen not to name the archive for now to protect the privacy of all parties involved and to guard against intrusions upon its digitalization process as the archive has now entered into a partnership with an institution in the global north.

[2] Luise White, ‘Hodgepodge Historiography: Documents, Itineraries, and the Absence of Archives’, History in Africa 42 (2015), 309-318.

[3] Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 15.

[4] Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008); Jane Lydon, ‘“Behold the Tears”: Photography as Colonial Witness’, History of Photography, 34.3 (2010), 234–50; Mieke Bal, Double Exposures: The Subject of Cultural Analysis. (New York: Routledge, 2012); Jane Lydon, The Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights. (Sydney: NewSouth, 2012); Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London: Verso, 2012); Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

[5] Mieke Bal, ‘The Politics of Citation’, Diacritics, 21.1 (1991), 26.

[6] Jennifer Tucker and Tina Campt, ‘Entwined Practices: Engagements with Photography in Historical Inquiry’, History and Theory, 48.4 (2009), 2.

[7] Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, ‘When is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words?’, in: Photography’s Other Histories, eds. C. Pinney and N. Peterson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

[8] See Gaynor Macdonald, ‘Photos in Wiradjuri Biscuit Tins: Negotiating Relatedness and Validating Colonial Histories’, Oceania, 73.4 (2003), 225-242; Tommaso Sbriccoli, ‘Between the Archive and the Village: the Lives of Photographs in Time and Space’, Visual Studies 31.4 (2016), 295-309; Jane Lydon, ‘Democratising the Photographic Archive’, in: Kirsty Reid and Fiona Paisley, Sources and Methods in Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive (London: Routledge, 2017), 13-31.

[9] See Kimberly Christen, ‘Relationships, Not Records: Digital Heritage and the Ethics of Sharing Indigenous Knowledge Online’, in: The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, edited by J. Sayers (Routledge, 2018); Temi Odumosu, ‘The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons’, Current Anthropology 61 (2020), 289-302.

[10] Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019), 42.

[11] Ahmed, On the Uses of Use, 12.

[12] Luise White, ‘Hodgepodge Historiography: Documents, Itineraries, and the Absence of Archives’, History in Africa 42 (2015), 309-318.

[13] It is important to add here that former colonial metropoles, such as London and Paris, tend to hold bigger parts of that detritus than the formally colonized places. This does not make it easier for those with less access to time and money to conduct research, often on the past of their own societies.