What do we know when we see?

Or how can museums of “the world” renew cultural geographies? A view from the State Museums of Dresden

Museums that have built collections of “world cultures”, known to us today as either ethnological or the more encompassing, encyclopedic museums, have not ceased to be the subject of impassioned debates. Even a cursory glance through the diverse and insightful contributions to this blog give us a sense of the poles along which deliberations over the recent years have tended to oscillate, that is, between the poles of postcolonial critique and contemporary multiculturalism. Beyond these two, now well familiar binaries, further positions in the discussion seek to complicate our understanding of the issues at stake. One such argument is that we adopt “a worm’s eye view”, as Kavita Singh has done[i], a micro-perspective from the locality. Such a shift of scale would immediately draw our attention to the fact that not all communities in a given region or locality speak from the same position as the official voice of the nation-state.

The tangled politics of individual regions where several critiques engage with each other is an inevitable consequence of the historical fact that the world is populated with nation states of different ages and distinct historical complexions. The institution of the museum per se has proved to be remarkably resilient and prolific. It is no longer attached to its parochial origins in Europe, but has travelled across the globe, has thrived in new localities, has morphed into new and unpredictable forms and continues to retain a magnetic aura. Not least, it remains a site upon which each nation, big or small, powerful or weak, manufactures its own version of the past and proceeds to project this on to the present and future. Such a version can be couched in the celebration of diversity, in other instances it rests on privileging certain strands of culture as mainstream national, while others are relegated to categories that are also hierarchies, such as “folk” traditions or minority cultures. A large number of museums in post-colonial or younger, post-cold war nations are being made to serve competitive nationalisms; at the same time, the growing global demand for new sights and spectacles has made them into places for the easy commodification of culture. In the West, where museums with encyclopedic collections were inextricably linked to practices of colonial collecting, ethical issues generated by their formative histories have led them to reinvent themselves as places to promote a Humboldtian cosmopolitanism. These museums are now being reclaimed as institutions that speak for the multicultural ethos of the societies where they are located – and indeed as being able to transcend these locations – as museums of and for the world.

I rehearse these familiar observations – that are also animatedly discussed in this blog – to simply point out that the issues at stake here, even as they are burdened with the legacies of the past, can no longer be entirely subsumed under the oppositions between erstwhile colonizers and colonies, rich and poor nations, the modern and the traditional. Though our ethical sense makes us reluctant to discard such explanatory categories, these are today overlaid by other, more urgent concerns and boundaries that cut through a globalized world and transcend those of individual nation states. The concerns we all share today are encapsulated in powerful catchwords such as xenophobic nationalism, fundamentalism, protectionism, migration and citizenship. More than a quarter of a century after the collapse of cold war polarities, even recent divisions such as between the Global North and the Global South have been breached in the wake of mass migration from West Asia and Africa, resulting in moves to firm up the boundaries of the West – the European Union and the United States of America. The presence of large immigrant communities in the midst of Western societies has generated discussions on citizenship and its nexus with culture: the meanings of citizenship as we know it is that of a juridical category that secures rights within a national framework. Today we also see it working as a tool for the bio-political regulation of illegality. It is a notion increasingly being questioned by theorists such as Giorgio Agamben, Etienne Balibar or the sociologist Saskia Sassen, all of who propose alternative models, such as “co-citizenship” or “shared citizenship” – i.e. a citizenship that is non-territorial, goes beyond being an institution determined by the nation-state, and includes solidarities that transcend borders of single nations.[ii] This is not an issue exclusive to established nations in the West when confronted with mass migration. In contemporary postcolonial societies too – India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Iran – narratives of citizenship and belonging are being recast within majoritarian frames that force allegiance to an officially fabricated cultural past. An urgent challenge facing museums as places of forging participative citizenship is how to envisage a political horizon for the subject and community that challenges the monologic exclusivity on which dominant versions of collective belonging are based.

A remarkable effort in this direction can be observed in the continuing initiatives of the State Art Collections of Dresden (SKD) over the past years. One example is the project “Europa/ Welt” conceived some years back by the idealist vision of the SKD’s then Director, Hartwig Fischer, and continued by his dynamic successor Marion Ackermann. The project strove to bring together the university and the museum, to conjoin art historical research to curatorial practice. “Europa/ Welt” was a move to destabilize outworn polarities between Europe and the rest of the world, to unpack the idea of Europe as an entity that was always, already formed through transcultural exchanges with the world. Such exchanges are embodied in the SKD’s rich collections.[iii] The curatorial challenge of such an ambition was to make the objects themselves bring forth their palimpsestic identities often in defiance of the stylistic labels ascribed to them that were circumscribed within fixed regions. One of the overarching principles informing this programme was that the museum of encyclopaedic scope could be made into a testing ground for a critical form of globality.[iv] The work of the museum collection was conceived of as that of problematizing the modernist ontologies that conflate culture with the modern nation-state; and to make the exhibition a space of self-reflection that would question our existing world-views that frame what we see.

The program unfolded through a series of exhibitions that drew almost entirely upon the permanent collections of the museum – these included the courtly collections of Chinoiserie, or the show entitled “Global Players” that featured objects from the Renaissance and Enlightenment whose material lives served as a medium to visualize the networks connecting Dresden to the distant corners of the globe in an age before the advent of modern travel and communications.[v]

Img. 1: Unkown Artist, August the Strong as Chief of Africans,

1709, SKD, Exhibition “Global Players”.

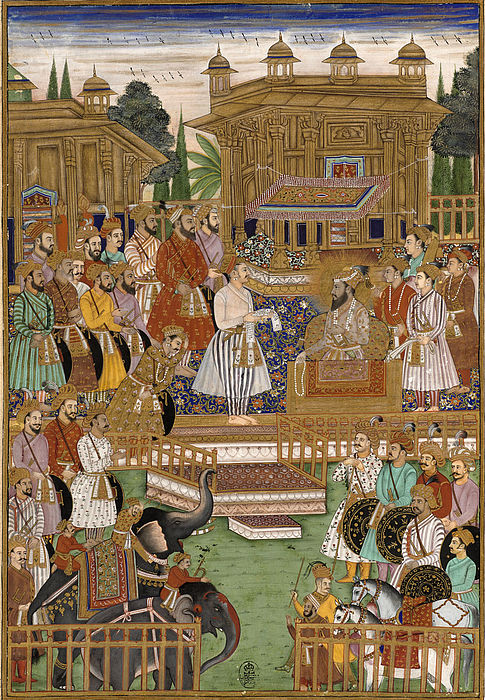

The exhibition “Miniatur Geschichten” was built around two collections of Indian miniature albums, one of which had belonged to the Indologist August-Wilhelm Schlegel, and that had hibernated in the museum vaults for over two centuries.[vi]

Img. 2: Unkown Artist, Audience (darbar) of Great Mogul Aurangzeb,

Dekkan-Mogul, early 18th century, SKD, Exhibition “Miniatur Geschichten”.

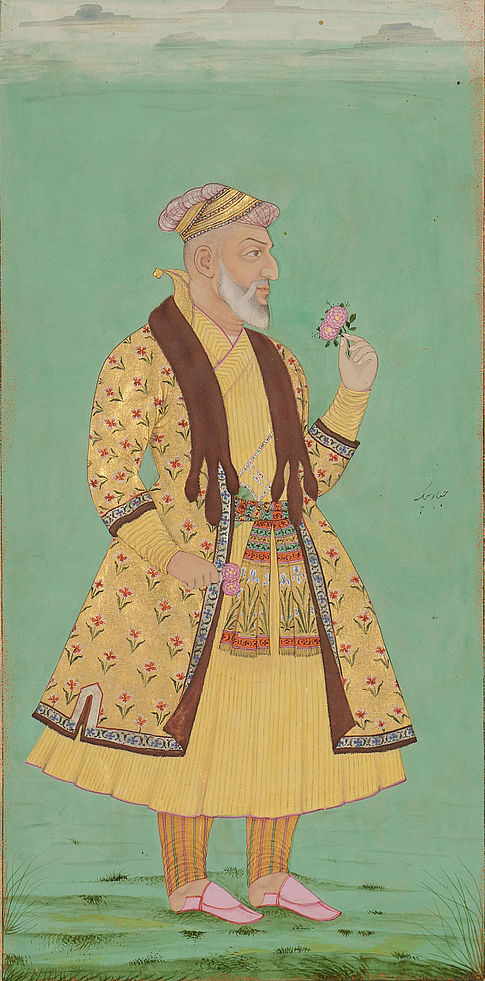

Img. 3: Portrait of Vizier Abd-al Jafar Beg, 1688-1689, SKD,

Exhibition “Miniatur Geschichten”.

The curatorial concept responded to the challenge of making a different kind of visuality accessible to a viewing public who would more often than not find it difficult to enter these ostensibly opaque images. Digital aids were used to allow viewers to “leaf through” the albums. Moreover the exhibition uncovered the tracks of this migrating art form, beginning with the production of the albums in a workshop at Golconda in South India, through their journeys in Europe, landing in the Netherlands and exchanging hands over the following century and a half. Thus, the visitor was encouraged to reconstruct the relationship between these objects and their makers, buyers, collectors, conservators and curators that connected all of them to distant cultures and places. Most importantly, this journey into the past worked to transmit the message that such objects were not simply reminders of exotic lands, but actually a living, formative element of those cultures they encountered and found a new home in. In the SKD’s conceptual frame the notion of the “world” is not conceived of as “the other” of Europe, nor is Europe imagined as either an originary centre or an ultimate focal point, but as simply one cultural strand among many that meet, intertwine, perhaps even separate, yet constitute and transform each other in the process.

This bare sketch signals to the potential of projects like the above to undo the effects of an ethnocentric art history and museum practice based on a separation of objects according to genres that disregard the historical and conceptual space that different objects had once shared. Projects like Europa/Welt can disrupt conventional and mechanical associations between objects and places, or eschew chronology as teleology. They can make different cultural geographies visible by following the narratives of the objects, made possible when display and room arrangements follow these narratives, rather than vice versa. For instance, a thematic rather than stylistic arrangement that would pull objects out of separate rooms, could allow a view into the connected histories of delineating the human form across Europe and Asia during late Antiquity. Or a re-assemblage of representations of Christian themes – for example, placing a Renaissance Madonna next to a Mughal or Chinese painter’s rendering of the same – allows us to follow the pathways of Christianity as it was transcultured into a global resource. Would we then continue to view the cross as a purely ethnocentric symbol; alternatively can such reassembling equip us to discern instances when it gets instrumentalized for populist ends?

And finally, to follow “Humboldt’s Legacy” also involves transcending the separation between art and science. Again, collections from around the world are best equipped to recuperate cosmologies that unsettle the division between nature and culture central to ontologies of modernity, by making tangible a more capacious notion of culture, as something co-produced between the human and the non-human world.

Museums that collected the world in the 18th and 19th centuries claimed the epithet of universality, a concept considered by many as philosophically untenable in the 21st century.[vii] Can we, taking a cue from Susan Buck-Morss, recalibrate the universal to respond to the exigencies of the present? The universal was never a static term, but one that underwent several shifts in meaning over the past two centuries. Buck-Morss urges us to interpret universality as a mode of denationalization. The universal in this sense no longer stands for inclusivity, that is, pulling everything into a single narrative, but for a method and a form of intervention in history.[viii] Similarly the curator and cultural theorist, Ranjit Hoskote, speaks of a “critical transregionality” as an alternative to exhausted cartographies such as those of the Cold War or of the Clash of Civilizations or of the West and the rest. He speaks instead of “continents of affinity”.[ix] Applied to the context of the museum, the universal today need no longer stand for totality or specularity, nor an ideal of plenitude, but as a new tool to think with, as a step towards liberating location from geography, culture and belonging, from the bounds of the nation state, and to build instead a lattice of transregional connections amongst institutions and curators based on a search for commonality in the face of jointly faced crises. Such a step would be both ethical and aesthetic.

Monica Juneja is Professor of Global Art History at the University of Heidelberg. Her research and writing focuses on transculturality and visual representation, the disciplinary practices of art history in South Asia, the history of visuality in early modern South Asia, Christianisation and cultural practices in early modern South Asia, heritage and architectural histories in transcultural perspective. Her recent publications include EurAsian Matters. China, Europe and the Transcultural Object (2018 with Anna Grasskamp); Miniatur Geschichten. Die Sammlung indischer Malerei im Dresdner Kupferstichkabinett (2017, ed. with P. Kulhlmann-Hodick); Kulturerbe Denkmalpflege transkulturell: Grenzgänge zwischen Theorie und Praxis (2013, with M. Falser); Disaster as Image. Iconographies and Media Strategies across Asia and Europe (2014, with G.J. Schenk). She has worked in advisory capacity to the project Europa/Welt at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden and is a scientific advisor to the exhibition Mikrogeschichten einer ex-zentrischen Moderne that is part of the project museum global and will open at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, Düsseldorf in November 2018.

––––

[i] Kavita Singh, “Who wants the world? Universal museums, a worm’s eye view”, unpublished talk given at the Humboldt University, Berlin, April 14, 2011.

[ii] Giorgio Agamben, “Jenseits der Menschenrechte”, in Mittel ohne Zweck. Noten zur Politik, Berlin: Diaphanes 2001; Etienne Balibar, Citizenship, Cambridge: Polity, 2015; Saskia Sassen, Territory, Authority, Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

[iii] See the booklet, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden. Europa. Welt, SKD, 2017.

[iv] „Interview zum Thema Global Art History. Elf Fragen von Gilbert Lupfer an Monica Juneja“, in Dresden. Europa. Welt, pp. 9-15.

[v] Jan Hüsgen, Anne Vieth et al, „Studiolo“, in Dresden. Europa. Welt, pp. 52-69.

[vi] Exhibition Catalogue Miniatur Geschichten. Die Sammlung Indischer Malerei im Dresdner Kupferstichkabinett, eds Monica Juneja, Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2017.

[vii] Tom Flynn, The Universal Museum. A Valid Model for the 21st Century?, n.p. n.d.

[viii] Susan Buck-Morss, Hegel, Haiti and Universal History, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009, esp. Part II.

[ix] Ranjit Hoskote and Nancy Adajania, “Notes towards a Lexicon of Urgencies”, in Independent Curators International Research, October 2010. http://curatorsintl.org/research/notes-towards-a-lexicon-of-urgencies (last accessed May 28, 2017).