Photographs and colonial history in the museum

In Britain colonial history has, uncharacteristically, been headline news recently. This is not merely a post-Brexit vote sensitivity (well what is our history?), although this might be a deeply buried part of the narrative. There are growing concerns about the visual conditions and public engagement with Britain’s colonial past. First were the demands from post-colonial activists that a statue of arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes be removed from the street front of Oriel College Oxford (it wasn’t, but only after much debate), then a row over the renaming of the well-established public venue, the Colson Hall in Bristol, long named after local 18th century slave trader and city philanthropist, and then the row emanating a project entitled ’The Ethics of Empire’. This latter was initiated by an Oxford theologian, and called for a reappraisal of the balance between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in the telling of colonial history and questioning dominance of, indeed assumption of, the latter in both historical debates and public representations within a multi-cultural society. This position brought letters to the press and a long and measured response from over sixty Oxford historians and anthropologists. These moments of protest and re-examination of the uncomfortable truths of British colonial history suddenly brought the debate into the public arena. But interestingly, no one discussed how that history might be engaged with in the public sphere beyond the removal of a statue – or not. Museums, as major vectors of public history and educative intent, have been largely absent from the debate, and the main UK sector magazine, The Museums Journal, strangely silent on the matter.

This seems a missed opportunity. Because while all these discussions were raging, notably this most recent one on “The Ethics of Empire”, there was, nestled away in a top gallery at Bristol City Art Gallery and Museum, a small exhibition of photographs that tried to raise and explore questions of the multi-vocal experiences of Empire and colonial legacy: “Empire Through the Lens”. It is on this small but timely intervention that I want to focus, because it raises questions not only about the representation of colonial history in the public space, and thus within the broader remit of the Humboldt Forum, but also addresses the opportunities and problematics of photographs in communicating this history. I shall return to specifics of the exhibition below.

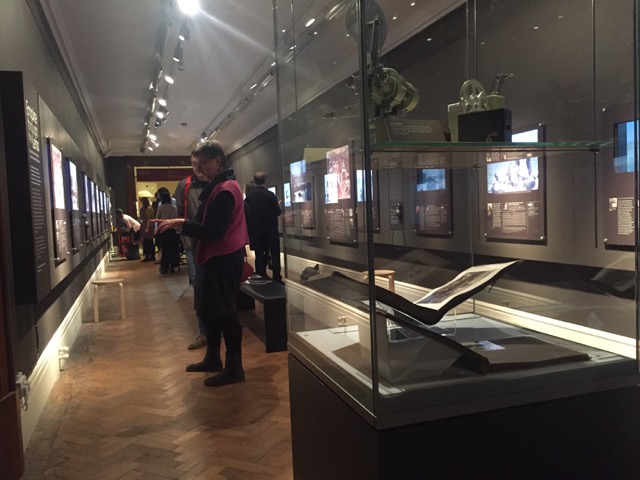

1.View of the Exhibition Gallery. © Bristol Culture

The background to this particular articulation of colonial history in the public space is interesting and part of the troubled visibility of that history. The Exhibition ‘Empire through the Lens’ drew on the photography and film collection of what was British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (BECM) in Bristol. The history of this troubled institution is significant in itself. Its presence was controversial and it never attracted public funding despite repeated applications. One strongly suspects that this was largely because of its subject matter, for it was rather a good museum in the way that it collected and presented its narratives, winning various museum awards. Public funding could not be seen to support something so controversial and potentially ‘racist’ within a multi-cultural society. Consequently BECM was dependent on private funding and donation from sources, which perhaps had very specific revisionist views of imperial history. The museum closed in 2013 after eleven years in existence. The museum’s collections were eventually transferred to the care of Bristol City Museums, Galleries and Archives, where BECM’s photography, film and manuscript collections were absorbed into Bristol City Archives. The work of archival absorption and documentation has been funded by National Archives, itself finding new ways to engage with colonial photograph collections. The Bristol exhibition is the culmination of this first phase of this project.

I have discussed elsewhere the problems of amnesia and especially, following Ann Laura Stoler, aphasia[1] in relation to museums and the representation of the colonial past, and of the sequestration of such histories to a series of elsewhere – of time, place and discipline (anthropology/ethnography) – as a way to avoid analytical responsibility for difficult histories in the public space. The move of the BECM collections into a publically funded and curated space, and the recognition of community relevance, does indicate perhaps a confrontation with that amnesia and aphasia and an increasing willingness to consider these histories. For Bristol with its strong and problematic history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, its subsequent wealth, built on post-abolition colonial trade routes, notably in tobacco and coca, and subsequent diverse population provide a robust background for the consideration of the legacies of Empire. They are inescapable.

The projection of these histories into the public space in exhibition form therefore offered a challenge. Furthermore what was particular about offering the public photographic access to the colonial past., as opposed to object or textual based access? In many ways the recodability of photographs, their slipperiness yet sense of immediacy which can be so problematic in Museums became that starting point of the exhibition. In an act of devolved and dispersed curatorship, 27 people – curators, artists, community and religious leaders, activists, descendants of colonial officers, and academics were invited to choose one image each from the collection of some 500,000 images. They were asked to talk about its history and about why it connects to their interests in the history of Empire. What was the place of Empire in their experience?

The exhibition stressed the way in which historical truths are, largely, partial truths in both senses of the word. The personal story approach meant that the sense of immediacy and directness offered by the photographs was mirrored by a sense of narrative immediacy and relevance as an on-going history. Few of the 27 selectors presented a straight-forward narrative. The challenge to aphasia emerged variously in the form of anger, outrage, a sense of injustice, sadness, nostalgia and curiosity in almost equal measure. Importantly they coexisted and were ‘speakable’.

2.1995/076/1/1/15/3.20 © Bristol Culture/ British Empire and Commonwealth Collection.

3. 2012/001/6/7/AM5 © Bristol Culture/ British Empire and Commonwealth Collection.

4.2002/133/1/34 © Bristol Culture/ British Empire and Commonwealth Collection.

The ‘openness’ of the curatorial process meant, inevitably, some unevennesses in the exhibition – geographical (a preponderance of Africa and India), informational, or stylistic, and the light curatorial editing style adopted to allow the immediacy of voices and connection to the photographs, also meant that there were factual inaccuracies. However, believed as part of the subjective and individual responses to and engagement with Empire, they became part of the multiple layers of historical assessment inherent in making histories. These readings were what made these photographs speak to their selectors. What kind of challenge does such multi-vocality of interpretation, especially linked to the reality effects of photographs, pose for the museum as didactic space? For photographs can be risky things in museums. Their directness, immediacy, yet fluid and unstable meanings can make them difficult to control in museum contexts – they are always open to [mis]interpretation with a propensity to undermine the curators’ intentions. And because of visitor expectations of how photographs should behave in the didactic space of the museum, critical uses have proved difficult to articulate curatorially, especially in relation to historical material. In many ways Empire through the Lens did what photographs do so well if they are allowed a dynamic identity within the museum space: they acted as a moment of temporal and spatial stasis, incisions into complex experiences, but simultaneously form a springboard for multiple histories: an address to a reality which was simultaneously constituted of multiple realities.

The display installation made those subjectivities very clear. The 27 photographs (or 23 and 4 film clips to be precise), dating from the 1880s to the 1960s, were presented as uniform, enlarged, back-lit images on the walls of a long, narrow and dark gallery. The back-lit images sparkled in the space, but allowed an extra luminosity of detail that encouraged a slow looking at the image. The intention was to personalise narratives as strongly as possible so as to stress points of view. These light box panels carried the texts in which selectors described ‘their’ photograph and its contexts, and why it connected to their particular interests, concerns and interpretations of colonial history. The voice of the selectors was given further presence by the inclusion of small photographs of them and audio-points which gave the selectors’ voice, as they talked in more detail about ‘their’ photograph. Some accounts were very personal, based in memories, or even nostalgia, others were more political or historiographical. All focused intensely on the image itself.

But to avoid the unproblematic window on the world, the mere absorption of photographs in a museal ‘economy of truth’ as Gaby Porter put it many years ago,[2] down the centre of the gallery space was a series of cases in which the original photographic objects and their contexts, such as albums, photo-folders, or slide-viewers, were displayed. This immediately positioned photographs not as windows on the world but as things that were materially produced and handled, which produced effects through modes of viewing and use. It anchored them materially to their historical moment. While I have long advocated material approaches to photographs as an intellectual and analytical position, the efficacy of such approaches within the museum spaces is perhaps less certain. What can the museum visitor learn from the materiality of photographic objects, not merely image content? In many ways the humble items of packaging, the family albums and hand-held cameras in this exhibition anchored both the specifics and generalities of the photographs, in time, place and action. It positioned them in material worlds beyond mere image content, and stressed the making of the photographs and all that that implies.

5. View of the Exhibition Gallery. © Bristol Culture

Importantly, there were recurrent themes of gravitational pull that wove both photographic selections and responses together –exploitation, alienation, power over places and power over bodies. Questions of power saturated the exhibition and some of the photographs articulated this with shocking force, notably in uncomfortable truths of colonial racial hierarchy. Crucially all the selectors saw the photographs as relevant today. Technologies and formats might have changed but the issues haven’t. And this was echoed in responses to the exhibition, for instance one blogger noted the “relevance of the images to current events and challenges still faced by post-colonial nations were very eye-opening”.

This sense of relevance is important, because a discourse of ‘irrelevance’ has masked the processes of amnesia and aphasia. No debate was necessary because it was ‘irrelevant’ to modern Britain, and thus enabling the colonial past to be sequestrated in the ‘elsewheres’ that I have noted. This is clearly not so here, as both the exhibition and the events with which I started show. Anecdotal evidence from museum front-of-house staff is that the exhibition is bringing in a wider visitor demographic than most exhibitions. There have been a number of well-attended public events and lectures, school visits and a social media buzz which suggests that at least at a local level, the exhibition has disrupted the collective amnesia and the patterns of aphasia, for all the various communities in Bristol and beyond for whom Empire is a shared and intersecting history. It has become ‘relevant’, recalled from its ‘elsewhere’.

There have been some Tweets claiming that such an exhibition glorified or excused the colonial. Interesting many of those appear to have been responses to the pre-publicity before the exhibition had actually opened. But they reflect an assumption about what colonial history is, and what any attempt to articulate it might be. However, the vast majority of visitors have been disturbed, yes – and so they should be from whatever their perspective, but they have also been stimulated to think about how and why these histories are relevant, and above all, the ways in which the colonial past should be within the public debate, including museum debates. (For examples of comments scroll to the bottom of the page).

Time will tell if this now-opened debate will sustain. Is this an exhibition from which there is no return? For a city so embedded in long imperial histories one hopes that such an exhibition shifts the dynamics of the larger historical narrative in the museum and its local engagements. Is this a local moment or part of a wider debate? To think that the recent debates might be marked as a shift from aphasia to loquaciousness in the articulation of colonial histories might be optimistic. The problem remains about how exactly these narratives, and their infinite complexities, can be articulated in the museum space. The exhibition also raises, as I have suggested, broader questions about the work of photographs in museums, and their ability to draw people in through that sense of the presence of the past and confront, through their very reality effects, the aphasic and amnesiac. It seems that this is an area where photographs, with their complexity and continual play between the subjective and the objective, the individual and the collective, their eloquence yet incompleteness, and their reach into unarticulated corners of historical experience may be a good place to start because as museum objects they themselves demand the same complex attentions that the colonial also demands.

And if anyone is interested in my selection for the exhibition – here it is:

(scroll down to “Letembia and Ann”)

Elizabeth Edwards is a visual and historical anthropologist who is currently Andrew W. Mellon Visiting Professor at VARI (the Victoria and Albert Museum Research Centre) in London. Until 2005 she was Curator of Photographs and Lecturer in Visual Anthropology at Pitt Rivers Museum/University of Oxford before leaving for academic posts. Now retired, she is Curator Emerita at the Museum, Emeritus Professor of Photographic History at De Montfort University, Leicester, and Honorary Professor in the Department of Anthropology, University College London. Specialising in the social and material practices of photography, she has worked extensively on the relationships between photography, anthropology and history. Her monographs and edited works include Anthropology and Photography (1992), Raw Histories (2001), Photographs Objects Histories (2004), Sensible Objects (2006) and The Camera as Historian: Amateur Photographers and Historical Imagination 1885-1912 (2012), and, over the years, some 90 essays in books, journals and exhibition catalogues on topics as diverse as photography and evolutionary theory and photography and sound. In 2014 she was given a lifetime achievement award by the Society of Visual Anthropology (American Anthropological Association) and a Photographic Studies lifetime achievement award from the Royal Anthropological Institute in 2017. In 2015 she was the first photographic specialist to be elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

For more information and publications see: https://dmu.academia.edu/ElizabethEdwards

____________________

[1] A psychological condition which causes inability to speak of or find the words for. Ann Laura Stoler 2011 “Colonial Aphasia: Race and Disabled Histories in France” Public History 23(1): 121-56.

https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/view/220/233; https://www.academia.edu/30481518/The_colonial_archival_imaginaire_at_home

[2] Porter, Gaby, 1989 “The Economy of Truth: Photography in the Museum” Ten-8, 34, 20-33.