Evidence and Fiction: An Untimely Alliance with the Photography Archive of Margot Dias and Jorge Dias

DCNtR Debate #3. The Post/Colonial Museum

The work of the Portuguese ethnologist António Jorge Dias (Porto, 31 July 1907 – Lisbon, 1973) and his wife and collaborator Margot Dias (Nuremberg, 4 June 1908 – Oeiras, 2003), a German national, important also for its sheer volume, produced a very abundant quantity of archival materials. Nevertheless, Portuguese anthropology’s history has assessed the work of Jorge Dias essentially on the basis of his intellectual and ideological output.[1] In this particular framework, Dias’ work marks the paradigm shift within the Portuguese anthropology from the dominance of anthropobiology towards a particular branch of culturalism. His influence emerged at the end of the first half of the 20th century, in the last period of the Portuguese colonial era. Margot Dias, a professional pianist who moved her focus to ethnography and ethnomusicology, mainly worked as part of Jorge Dias’ expedition team, in particular the expeditions to Mozambique and Angola, where she pioneered using film and sound recordings. After the death of her husband, she carried on as guardian of his legacy and devoted herself to continuing the work she had begun with him. Although the publication of her film records on DVD has recently highlighted her contribution to Portuguese visual anthropology[2], their fieldwork has been little studied and explored. Their documentation consists of various media (journals, photography, film, and sound recordings) and can mainly be found in Portugal at the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon, an institution to which Jorge Dias contributed during its foundation in 1965 (at the time it was called the Overseas Ethnology Museum). In some cases, these materials are centralised and meticulously organised, while in other instances they are scattered or have shortcomings in terms of access and organisation.

This visual essay will focus on a selected group of images, which originated from an anthropological mission to the Makondes between 1957 and 1961 that Jorge Dias headed. This mission happened within the scope of the Mission of Portuguese Overseas Ethnic Minority Studies (Missão de Estudos das Minorias Étnicas do Ultramar Português) as an activity of the Overseas Research Council (Junta de Investigações do Ultramar). Directly subordinated to the Ministry of the Colonies/Overseas, the entity’s main function was to coordinate the scientific studies, that were to be undertaken in colonial territories under Portuguese rule. Beyond the objectives proper to applied anthropology, the creation of those missions was linked to the attempt to diagnose and correct potential threats to Portuguese sovereignty coming from local movements in those territories, but also from those coming from neighbouring countries. In this respect, special attention was given to the study of the Makondes in the region of the Mueda plateau, because it is situated close to the Tanzanian border, on the territory of modern-day Cabo Delgado Province in the North of Mozambique.

This essay not only focuses on the Dias’ photographic collection, but also regards it as an original creative act, thus permitting an intentional distancing from its subsequent disciplinary and scientific uses. The metaphorical choice of words for the title emphasises this same intention: to allow the research to go in and out of the central object, like in a dialogue with a living, complex, and incomplete figure. In my artistic research[3], this translates into using an intertextuality between historical periods and disciplinary fields, while also approaching and relating diverse documents, be they objects, photographs, film or architecture. Beyond the concrete work that underlies the research – like searching for ›lost‹ parts of collections, reconstituting never-published books, and telling invisible micro-histories – I intend to displace the archive’s nature out of its pretended neutrality in representation, in order to allow thinking the photographic inventory medium retroactively anew as a fostering technology for concepts such as ›authenticity‹ and ›coloniality‹.

Fig. 1: NAMPULA

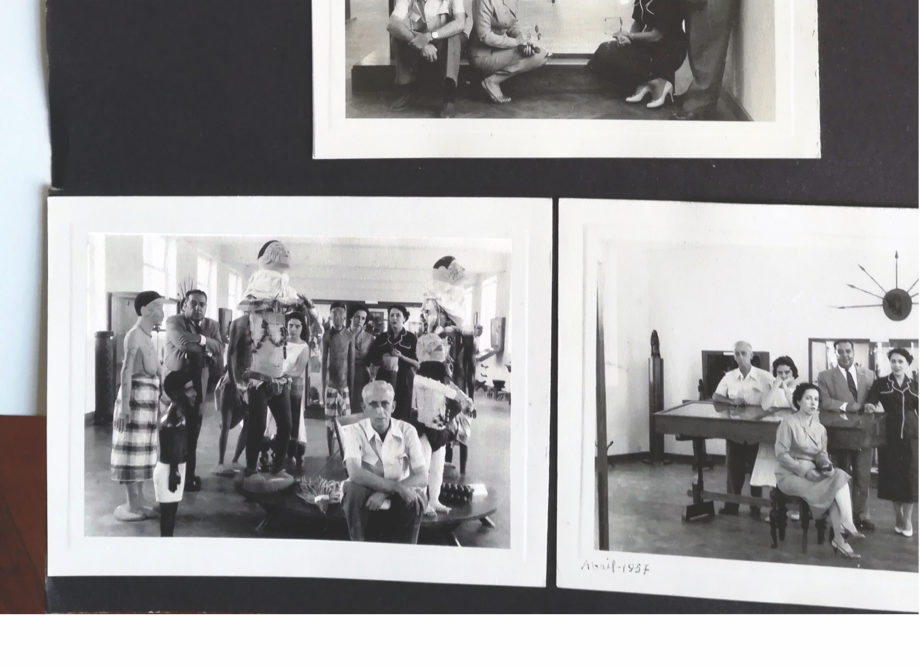

Fig. 1: NAMPULAIn March 2018, I visited the National Museum of Ethnology in the city of Nampula, in northern Mozambique, and met the current director Mr. Kulyumba and his team. At the time, I showed them on my mobile phone a series of five black and white pictures. The team managing the Museum was not familiar with these photographs, despite having been taken sixty years ago at exactly the same place where we met. In one of the photographs, I helped identify the first two curators of the museum when it was inaugurated in 1956 under the name Commander Eugénio Ferreira de Almeida Regional Museum. In the image, the two curators were photographed with their families, standing in curious poses, camouflaged among sets of life-size wooden human figures that displayed ›ethnic scarification‹, Mapiko masks mounted on mannequins (or sculptures?), and other artefacts associated with initiation rites. At my request, one of the museum staff went and brought similar items from different sites in the building, until he had finally gathered a small set of objects that he recognised in the photograph, setting them out before me so that I could photograph them. This staff member thereby carried out the sequence of procedures that a photograph in a museum generates by acting as an index of the object. We are familiar with the fact that photographs are used in a museum to reference and catalogue its collection. However, this access system, which organises and reports documents in relation to each other, does not seem to exist in the same manner throughout the world. From the early years of its activities, citing a lack of resources, the Nampula Museum was gradually abandoned and finally closed. With the decolonisation process (1974–75), a part of the collection was taken by the colonisers, who returned en masse to Portugal with whatever they could carry in their baggage[4] (see Vicente/George 2021). I was not wrong in presupposing that these photographic documents would not be recognised by the current staff of the Nampula Museum. I quickly accepted the idea that the broken link between the Museum and its archive was the result of the violent rupture between Portugal and its colonial space.

From another angle, it may in fact be easier to disown an object when it cannot assume the appearance of a memory, for the lack of evidence of its representation, omission of traces of its material and symbolic permanence. Further research led me to consider a new stigmatizing factor that, associated with the nature of the historic disturbance, would contribute to portraying the Museum of Nampula as a ghost museum.

Fig. 2: JOHANNESBURG

In May 2019, I collaborated with the Witswatersrand University Museum of Anthropology, where, along with the academic Caio Simões Araújo and the Museum director George Mahashe, I co-organised a workshop entitled Critical Entanglements: Colonialism, Anthropology and the Visual Arts[5]. This workshop focused on the year 1959 in order to reflect on the museum’s and university’s pedagogical and political framework. In that year, the Portuguese ethnologist Jorge Dias was invited to present a series of lectures, while his anthropological study on the Makondes in northern Mozambique was still in progress. At the same time, the political struggles for independence in Congo and Tanganyika were having a stronger impact on the northern region of Mozambique. The prospect of major political change was a constant concern for the team of ethnologists on this mission. Proto-nationalist movements were organised in exile or clandestinely within the country. The Portuguese Secret Information Service intensified arrests and recruited informants in the villages among the Makonde population, especially along the border with Tanganyika. In 1959, Professor Jorge Dias received an invitation from the Department of Portuguese Studies at Wits University, which was funded by Ernest Oppenheimer, the renowned South African magnate involved in the diamond trade. The six public lectures were entitled Portuguese Contribution to Cultural Anthropology, and his lecture The Makonde People of Portuguese East Africa was an especially noteworthy part of the series. In 1961, these lectures resulted in a publication by the University, in which the chapters were organised according to the themes examined in each lecture. This alignment clearly reflected the series of concerns set out by Jorge Dias (1961a) in that context[6]. On the one hand, the exceptional nature of the Portuguese case in the history of Africa and the process of African colonisation and, on the other hand, the advances made in anthropological studies of the Makondes in colonial northern Mozambique and in the province of Cabo Delgado.

Monograph

As part of Jorge Dias’ anthropological mission, a four-volume monograph (Dias 1964; Dias/Dias 1964; Dias/Dias 1970; Guerreiro 1966), entitled Os Macondes de Moçambique (1964–1970), was published and had an enormous impact as it circulated the results of their anthropological study on the social and cultural life of the Makonde. However, there was no indication of the disruptive effect of the Portuguese colonial occupation. In contrast, the problems and tensions among the Makonde population were described in Jorge Dias’ Mission Reports from 1957, 1958, and 1959. These reports were prepared at the request of the Ministry for Overseas Affairs and remained entirely confidential for many years. Being smuggled to Mozambique through networks sympathetic to the anticolonial movements[7] – and thus inaccessible to Portuguese researchers – these reports already informed the political elite and the first generation of post-independence Mozambican historians, contributing (somewhat ironically) to a reversal of the constraints of the colonial legacy.

Ethnographically Intimate, 2019

Alongside the workshop at the Wits Museum a selection of representative documentations, produced by Jorge Dias’ mission to Mozambique, were displayed in the atrium of the workroom. It was arranged in a way that the audience could critically approach the visual and materials that described the presence of the anthropological team among the Makonde. This installation was insightfully called Ethnographically Intimate. I contributed to the exhibit with a piece made from reproductions of photograph file cards that I obtained from the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon (MNEL). I selected a series of file cards from the complete collection of photographs that were taken by Dias’ team during the expedition to northern Mozambique. The photographic collection was organised in one of the museum’s filling cabinets in the year of the team’s expedition to Mozambique (1957–1959 and 1961)[8]. Of a total of 25 selected cards, I identified three specific sets for the exhibition Ethnographically Intimate:

(1) Micro-sequences: This set consisted of small reports prepared in Makonde villages using successive records to accompany the unfolding of a given ritual. The selection included Makonde initiation rites. The reason given in the monograph for omitting glaring aspects of change in favour of a timeless and traditional description of the Makonde people also ended up orienting the selection of ethnographic photographs toward static choices with singular descriptions. In contrast to the criterion used for the monograph, I was interested in the photographs that could not avoid the risk of a direct comparison with reality. Here, I appreciated the virtues of amateurism while taking the photographs, which inadvertently captured members of the Portuguese administration and the Western bodies and clothes of the ethnologists themselves, within the context of scenes of ›anthropological interest‹. These photographs were considered ›unsuitable‹, because they represented subjectivity, sensuality, fascination, fear, and intimacy.

(2) Micro-occurrences: I used the term micro-occurrences to describe clues that were not evident at first glance but which emerged due to the regular and methodical organisation of the files. The captions themselves, along with succinct comments, favour an objective appreciation of the images, while the gestures captured therein are clearly of another nature.

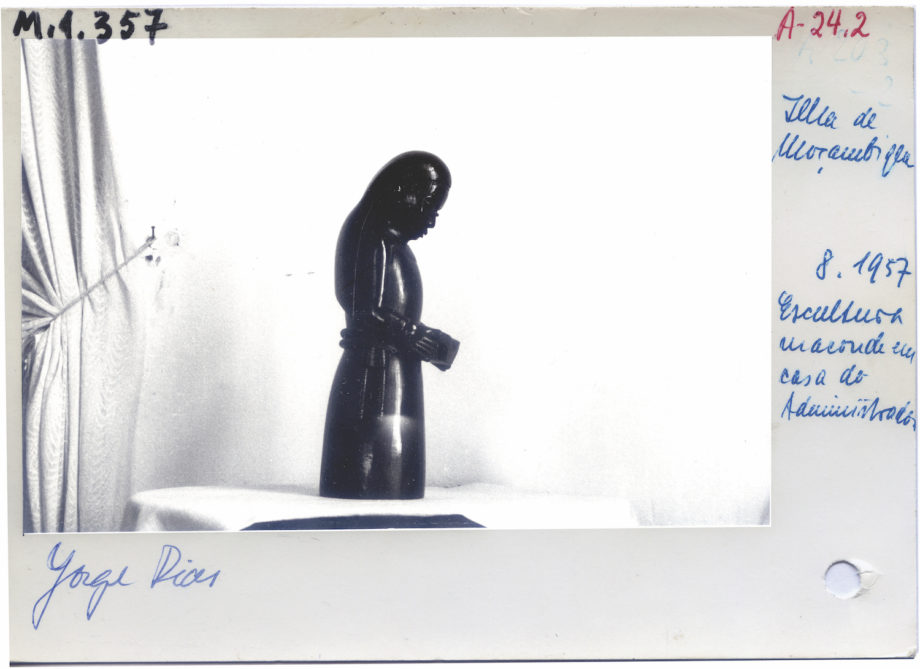

(3) Micro-absences: This photograph stands out from the set presumably because it shows a space that is not associated with the environment of the villages. This is a photograph that depicts the interior of the residence of the Portuguese Administrator of Mozambique Island and focuses on the ebony wood figure of a ›Makondised‹ saint that was on exhibition. The natural correlation established by this photograph is with the monograph volume that was never published – and which became known as the 5th volume. This was initially envisaged by Jorge Dias and Margot Dias to examine exclusively the theme of the Makonde wood sculpture. The task of compiling documentation continued, since Margot Dias paid constant attention to this theme (as is evident in several of her published articles), but the 5th book of the monograph was never concluded. Very little is known about what happened in 1973 after Jorge Dias died and Margot Dias continued trying to resolve the challenges that this volume raised for her and for the collaborators, she invited to assist her. I began my presentation during the workshop with this photograph to mark the shift of my research away from the disciplinary history associated with this archive.

Fig. 3: Photograph card: Mozambique Island; 8.1957. Makonde sculpture at the administrator’s residence. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm). Photograph collection, Jorge Dias/Margot Dias archives. National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

»Makond-ised« saint in a hall at the residence of the Portuguese Administrator of Mozambique Island, 1957.

The photograph card shows a wooden female figure captioned »Makonde sculpture«. While, on the one hand, it reflects the private space of a residence (with European curtains), it also shows a totally different type of intimate aspect: the intimacy between the team of anthropologists and the Portuguese colonial administration. Close ties with the administration were essential to be able to carry out fieldwork. Not only was this collaboration unavoidable, but it was also necessary for the logistics of anthropological expeditions, such as hiring a team of local assistants (drivers, interpreters, etc.), organising accommodation, vehicles, and other activities. In his (unpublished) Mission Reports, Jorge Dias criticised the brutal and uncultured way the Portuguese administration treated the indigenous population. Jorge Dias’ criticism was fuelled by a genuine belief in the theory of the exceptional nature of Portuguese »Lusotropicalism« in Africa, capable of promoting a harmonious fusion of allegedly »superior/inferior« cultures, as long as the »stronger group« is able to skilfully conduct »its assimilationist action« (Dias 1961b). In her field work notebook, Margot Dias showed herself to be more emotional than her husband and did not hide her irritation with the fact that European cultural practices tended to distort the population’s ›traditional culture‹. The commissioning of ebony sculptures, such as the one in the photograph, was part of the instrumentalization of the population by the Catholic religion.

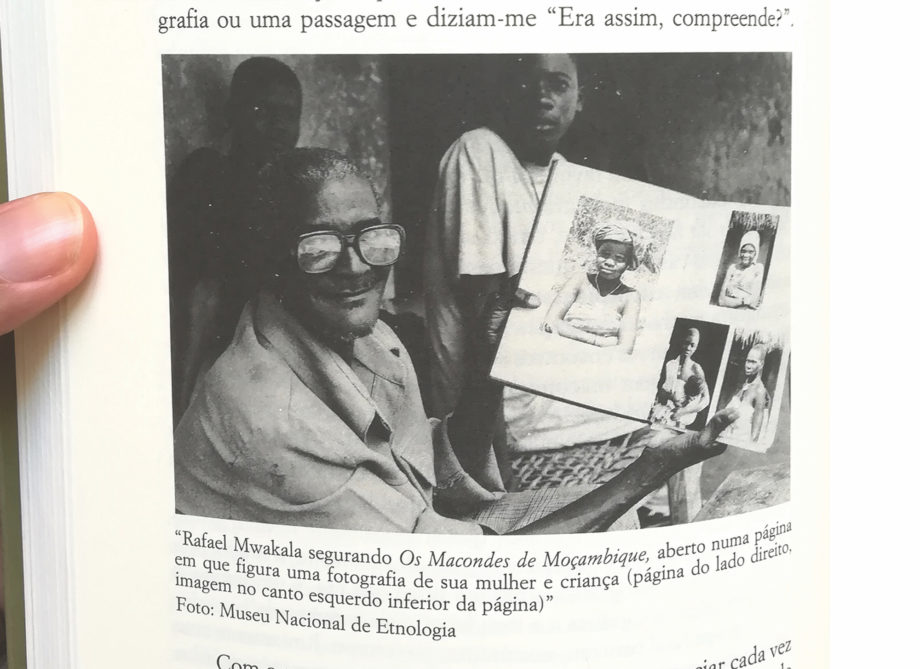

Fig. 4: Image reproduced in a book: Rafael Mwakala holding Os Macondes de Moçambique, open at a page with a photograph of his wife and child (right hand page, image at the lower left corner of the page). Photo: National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon. (West 2006: 150) Courtesy Harry G. West.

Rafael Mwakala in 1991, showing the monograph by Jorge and Margot Dias. Harry G. West. Photo taken from his 2004 article »Inverting the Camel’s Hump: Jorge Dias, His Wife, Their Interpreter, and I« In Significant Others: Interpersonal and Professional Commitments in Anthropology. (ed.) R. Handler. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. – here in the Portuguese version of 2006.

Between 1991 and 2005, the anthropologist Harry G. West carried out anthropological research on the effects of colonialism, war, and social reconstruction in the same district as Jorge Dias studied the Makonde in the late 50s. In an article published in 2004, West analysed Jorge Dias as the anthropologist who had preceded him by studying the same region of northern Mozambique on the eve of the Mozambique liberation war (1964–1974). The article described his meeting with Rafael Mwakala, the interpreter who accompanied Jorge Dias (he was his favourite interpreter) during an expedition he headed 30 years before. According to Mwakala, he was recruited expressly by Jorge Dias – who had not been satisfied with the level of his other interpreters’ Portuguese – at the Catholic mission where he lived, a few kilometres from the town of Mueda. In the photo, Mwakala can be seen smiling, holding the monograph Os Macondes de Moçambique, open at the page where his wife and baby appeared as objects of study in the book. Mwakala himself could not be included as an object in this monograph. He did not count as one of the ›traditional‹ Makonde. From the perspective of Dias’ team, he had been changed by the school and by the church, and he did not have the traditional physical markings on his body, the »scarification that would have identified him with his ethnic group«. However, they valued his intelligence and his proficient Portuguese and in Dias’ eyes, this made it possible for him to successfully carry out all tasks, which involved translating from the Shimakonde language to Portuguese, and vice versa. This fact was greatly appreciated by the team, since they did not speak any of the local languages. However, this was not the reason for the criticism that West voiced in his article.

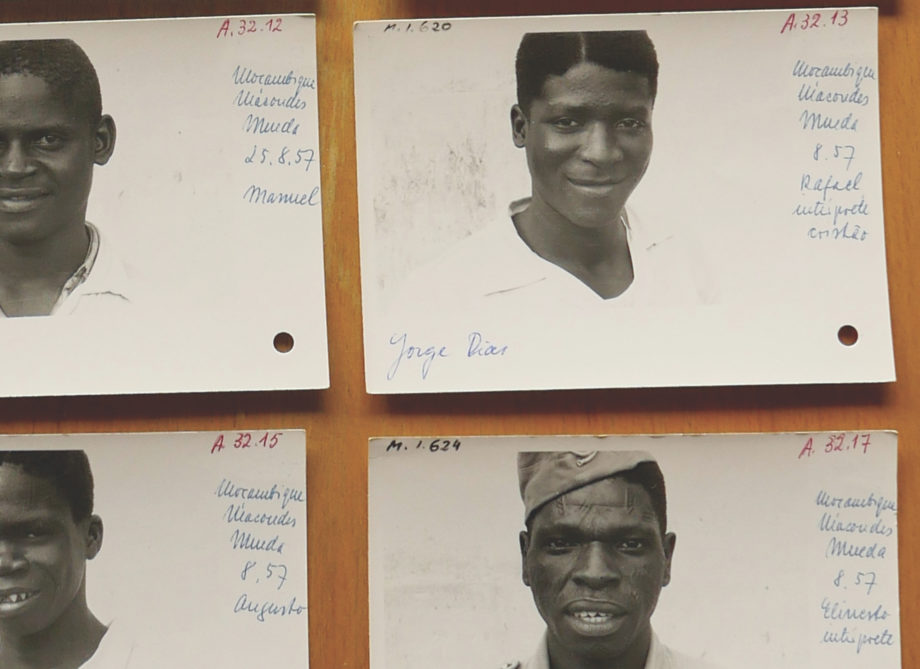

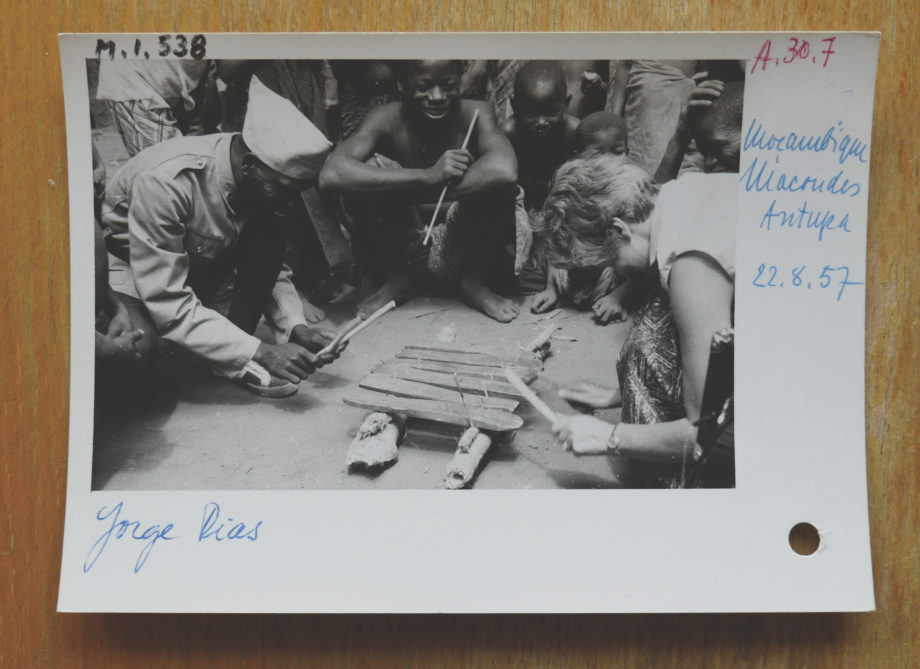

Fig. 5: 4 photograph cards. Upper right corner: Mozambique, Makondes, Mueda. 8.57. Rafael, Christian interpreter. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm). Photograph collection, Jorge Dias/Margot Dias archives. National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

4 photograph cards. Upper right corner: Rafael Mwakala shown in 1957, as a member of the »staff«.

The meeting between Rafael Mwakala and Harry West enabled the latter to ascertain the anthropologists’ impact on the Makonde community that they were visiting. He argues that, while the images printed in the monograph were proof of their ›traditional‹ and unchanged culture, their impact created a confused suspension of memory, affecting their identity. One of the revelations made by Mwakala West talks about, is about his own life at the time of the expedition. Rafael had been secretly involved in a proto-nationalist movement (MANU). From 1963 onward, he was even one of the first recruits to be sent to Algeria for military training by the newly-formed FRELIMO[9], which was created by merging three smaller movements (one of which was the MANU). West emphasises, that this radical aspect of Rafael’s life history is particularly useful to demonstrate what Dias and his colleagues were unable to envisage or at least failed to describe in their ethnographic work on the life of the Makonde people.

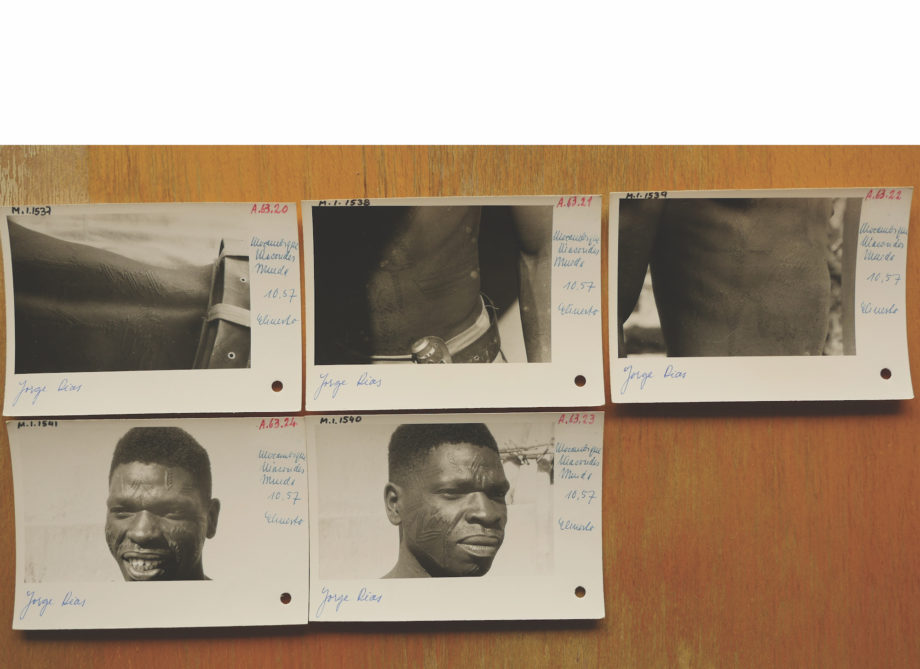

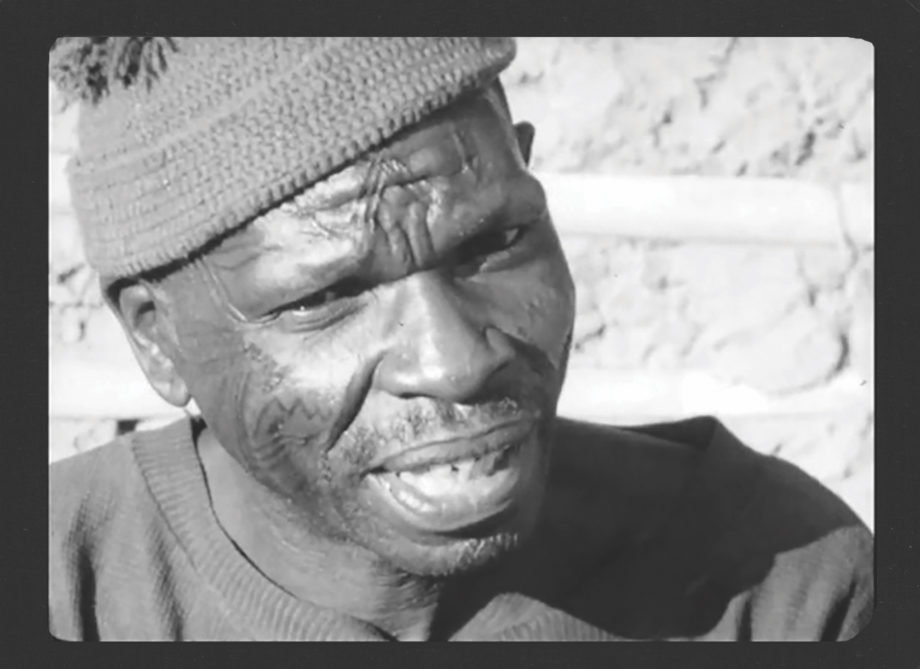

Fig. 6: 5 photograph cards: Mozambique, Makondes, Mueda. 10.57. Elinesto. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm). Photograph collection, Jorge Dias/Margot Dias archives. National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

5 photograph cards: Details of »Elinesto’s« body in 1957; scarification on the lower back, the abdomen and face; dental mutilation.

In this set of photographs, Elinesto reveals his skin (shown without sepoy uniform) to show five specific parts of his body. Unlike in the case of Rafael Mwakala, the tattooed body of Sepoy Elinesto qualified him to be a ›traditional‹ subject. Photographs of Elinesto appear in volume I of the monograph Os Macondes de Moçambique – Aspectos históricos e económicos (54) and in volume II, Cultura Material (14). The overlapping of Elinesto’s different functions – object of study, interpreter, and simultaneously a sepoy – sheds light on a certain procedure that originated in the colonial Portuguese administration. The administrator would choose from among the more qualified and ›trustworthy‹ individuals who worked for the local administration, indicating those who could serve as assistants for the anthropological team’s work. This group of local assistants would take the anthropologists to situations in villages in the region that were of interest to their studies. Generally, these villages corresponded to their own communities. Thus, the set of interpreters chosen by the Portuguese administration would end up determining the circuit of villages and the situations of interest recorded by the scientific team. The team of anthropologists could have been aware, or not, of the functional importance of the indigenous informers’ role as interface in their ethnographic work. However, the interpretation that this ›interface‹ had for the community of the villages was obvious. The community knew the psychological profile of the Makonde people working for the ›whites‹, who were forced to defend the interests of the colonizers and reject their own.

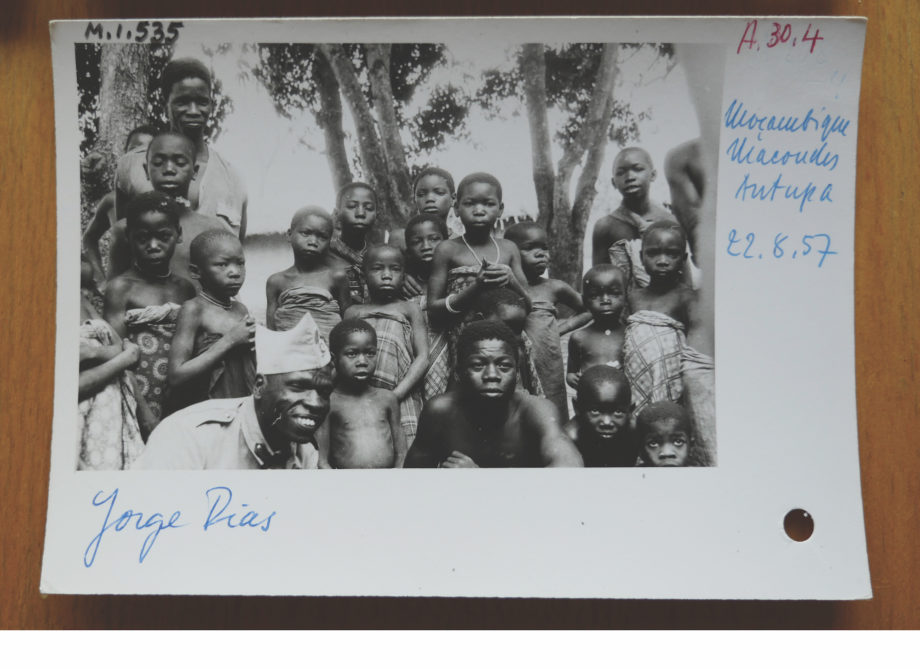

Fig. 7 and 8: 2 photograph cards: Mozambique, Makondes, Antupa. 22.8.57. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm). Photograph collection, Jorge Dias/Margot Dias archives. National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

2 photograph cards: Elinesto in his sepoy uniform in 1957; during an audio recording, Elinesto and Margot Dias simultaneously played a percussion instrument, surrounded by children and some adults from the village.

In the archives of the Portuguese Secret Police (PIDE) in Lisbon, Elinesto is described as a cruel, obedient soldier and he was therefore highly appreciated by the Portuguese administration of Mueda village. He was a ›good sepoy‹ and his name was always suggested whenever the Portuguese administration considered it ›necessary‹ to carry out harsh punishments against other Makonde. His name also appears in the documentation linked to events that sparked an incident of colonial violence on 16 June 1960 at the administrative post in Mueda. In Mozambique’s history, this incident became known as the Mueda Massacre. The term was strategically coined by FRELIMO during the armed struggle (1964–1974), which converted this event into a strong weapon of counter-propaganda at a time when Portugal was still promoting the narrative, that their colonizing actions were exceptionally mild – which the »Lusotropical« vision that Jorge Dias defended helped to cement. In 1959, Elinesto was summoned by the Mueda administration to escort the famous Makonde proto-nationalist Faustino Vanomba on his return to Tanzania. Indeed, Faustino Vanomba had come from Dar es Salaam to negotiate the return of the Makonde he was representing, who had immigrated to Tanganyika to escape the oppressive rules imposed by the Portuguese. They were making claims to regain power over their land in Mozambique, as the political changes for independence in Tanzania no longer ensured work and livelihood in that country, but at the same time exhibited a model of successful peaceful negotiation that leads to a radical power shift. According to the official PIDE dispatch, and demonstrating a complete antinomy with the political changes going on in the neighbouring country, Elinesto was to take steps en route to discourage Vanomba from returning to Mueda with such demands for independence (though he did nevertheless return, placing the two Makonde once again in conflict, as will be seen in the next chapter).

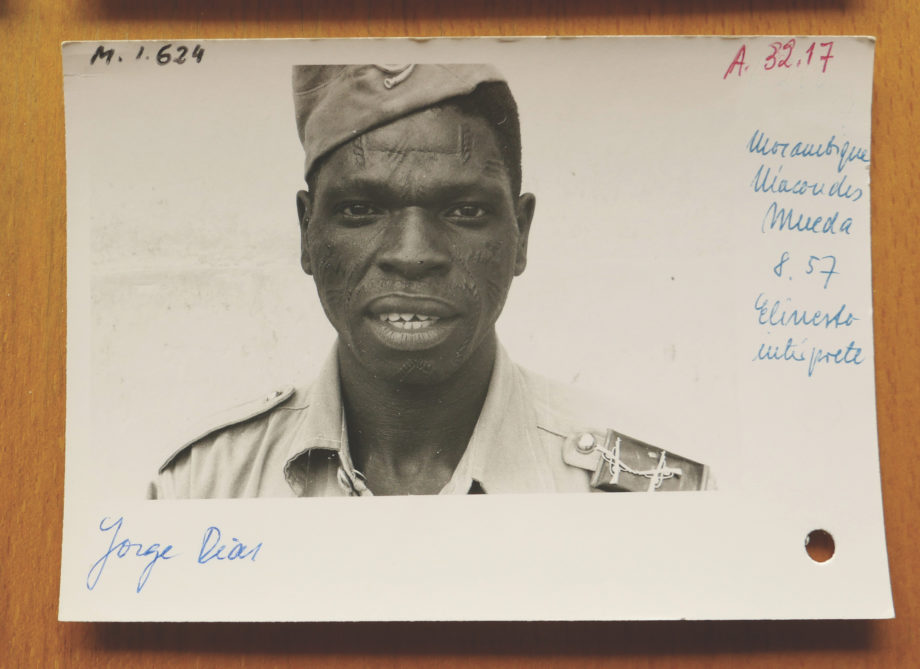

Fig. 9 und 10: 1 photograph card: Mozambique, Makondes, Mueda.8.57. Elinesto, interpreter. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm).

1 screenshot (distribution copy): Mueda, Memória e Massacre, Ruy Guerra, 1979–1980 (INC, Mozambique). INAC (Maputo)/Arsenal – Institute for Film and Video Art – Berlin. Courtesy Ruy Guerra.

1 photograph card: Elinesto in his sepoy uniform in 1957.

1 screenshot: Ernesto Tchipakalia in 1978, during one of the sequences of the film in which he appears: »I shot too. If they died, I can’t say, because they were all on top of each other. People died that day. A lot of people.

The film Mueda, Memória e Massacre, by Ruy Guerra, enshrines the legend of the Mueda Massacre as a national event. According to the official FRELIMO narrative, this was the watershed moment, the point of no return, which legitimised the use of weapons and the armed struggle to achieve independence. In 1978, Ernesto – who was no longer called Elinesto – was interviewed for the film as a witness of the massacre that occurred due to successive political demands and adverse attempts by the Makonde proto-nationalists to negotiate with the Portuguese administration. In the film, Elinesto introduces himself humbly: »My name is Ernesto Tchipakalia and I used to be a sepoy for the Administration of Mueda«. Subtly evasive, Ernesto Tchipakalia’s testimony is a mixture of a voluntary confession about his involvement in the massacre as well as his equally ambiguous conversion to the cause of independence, in which he »also killed… I don’t know if they died« and that »many people died«. Considering Ernesto’s/Elinesto’s psychology, his reappearance in official images, once the country became independent, could hardly have been accidental. In this aspect, his involvement in the 1979 film is similar to his role in 1957 during Jorge Dias’ and Margot Dias’ expedition. He already knew this role of obeying the authority in power and defending its interests and had embodied it so diligently. Of the testimonies the film compiled to narrate the history of the massacre, only two among them were from the side of the ›aggressor‹. But in the final (censored) version, only Ernesto/Elinesto appears in the film. The other testimony that of the erstwhile colonial administrator, was removed. Responsible for this was Garcia Soares, the Portuguese administrator responsible for the administrative post at the time of the Mueda Massacre. Soares spoke openly about the fact, that the incident had been adulterated by FRELIMO propaganda. Unlike the description the former administrator gave for the film, Ernesto/Elinesto is consistent with the official version of the massacre, in which, supposedly, 600 Mozambicans were killed by Portuguese soldiers. The claim, that Ernesto’s/Elinesto’s reappearance in official images was not accidental, is reinforced by the complete invisibility of Rafael Mwakala in the history of the struggle for liberation. According to Harry West, after Mozambique achieved independence Rafael left the FRELIMO to join the enemy movement RENAMO[10] once he saw that his value was not being recognised within the FRELIMO movement. The character of Ernesto/Elinesto can also be connected to TaTac Mandussi, the character of the administrator’s faithful sepoy in the film. It is said, that TaTac Mandussi was hung by his own people in a ›popular trial‹ for publicly claiming that the black people would not be capable of governing the country after independence. During that time, Ernesto/Elinesto remained silent and was therefore spared.

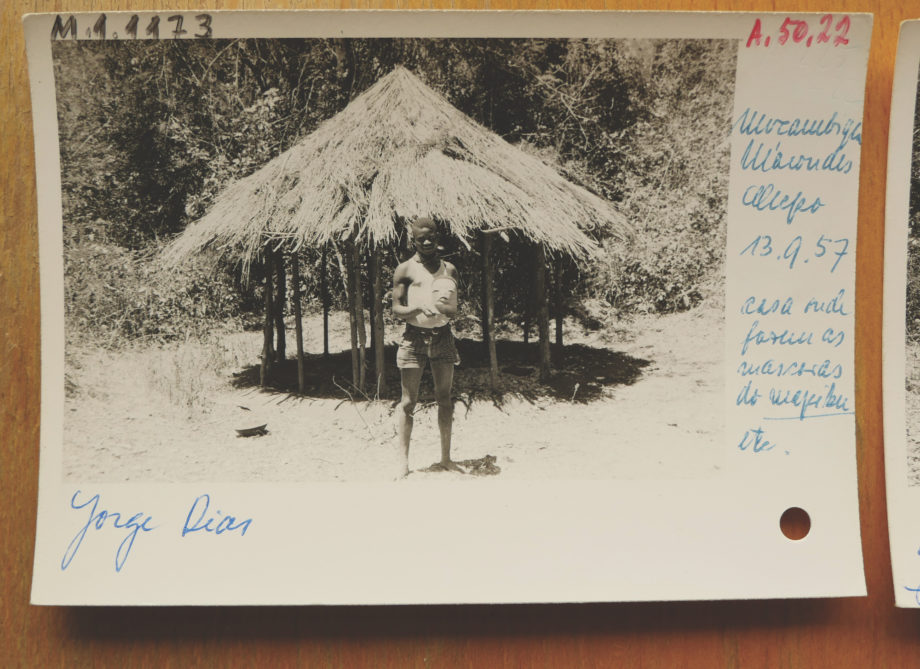

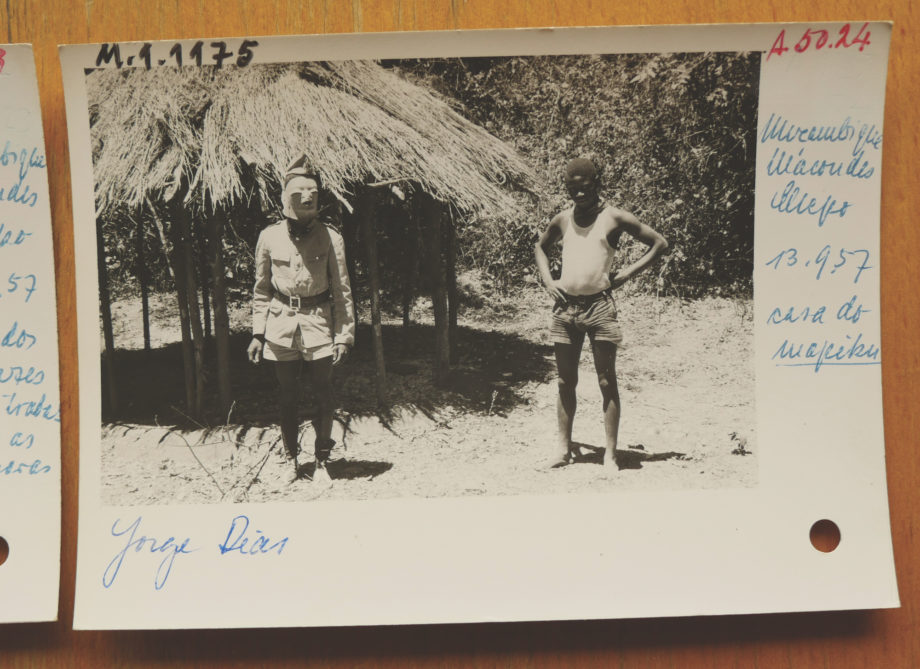

Fig. 11 and 12: Composition of 2 photograph cards. Casa do Mapiku. Jorge Dias. (14.7×10.6cm). Photograph collection, Jorge Dias/Margot Dias archives. National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon.

Composition of 2 photograph cards. Elinesto (Ernesto Nengo Tchipakalia) poses for a photograph with a Mapiku mask on his head. His sepoy bonnet, which identifies him, is placed on top of the helmet-like mask.

The card system of Jorge Dias’ and Margot Dias’ photograph collection plays an important role in the consolidation of their scientific narrative and in the perception of a heterogeneous unity. However, other ›possible‹ portraits and other characters can be extracted from the way the cards were organised. For this approach, it is necessary to work on a counter-factual basis, following the clues of micro-occurrences, such as, for example, the paradox contained in Ernesto Tchipakalia’s baptismal name. Ernesto, a Portuguese name, contains the sound of the r that is common in the Portuguese language (and which does not exist in Shimakonde). This means that in 1957, Ernesto pronounced his own name in a form that was adapted to his own language, substituting the sound of the r with an l. Later on in my research, I accidentally learned that he was more commonly known as Nengo among the Makonde. After independence, he stayed in Mueda until his death in the early 2000s. Those who knew him say, that he was a great supporter of the FRELIMO commemoration of the 16th of June, volunteering eagerly every year to speak publicly about his ›conversion‹ after defending the Portuguese on the day of the Massacre.

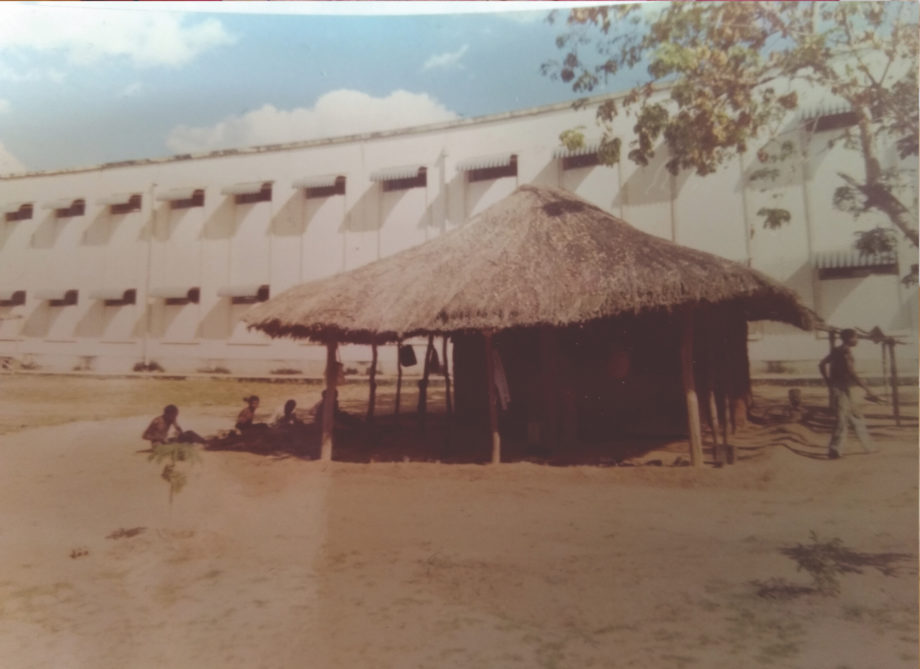

Fig. 13 and 14: Black and white photograph: Nampula Museum, 1956. Family album. Adelino Pereira/Avellar George archives, Lisbon. Courtesy João Pedro George.

Colour photograph: Thatched hut of Makonde sculptors (1986) built behind the Nampula Museum. Private album of a former GDR worker in Mozambique. Courtesy Bernhard Guttsche.

2 photographs: Front (1956) and rear (1986) of the Nampula Museum, Mozambique. In 1986, the thatched huts built at the back of the Museum hosted Makonde sculptors who came from Cabo Delgado to produce objects for the exhibitions. Paradoxically, the installation of the thatched huts recreated the ambience of the museum during the colonial period (as described in documents from the period). Even today, after visiting the exhibition, the public can leave by the rear door and see the Makonde sculptors work in that ched huts and temporary structures and can purchase items and souvenirs from them.

Nampula is the capital city of the province of the same name that is situated on the Mozambique coast and immediately south of the modern Cabo Delgado province. In colonial times, the Nampula Museum had an important collection of Makonde artefacts. This collection is a result of the ›administrative‹ acquisition of objects from villages in Cabo Delgado and also consists of pieces provided by staff and administrators in that region. Responding to an appeal for contributions, staff and administrators made personal donations to the Museum’s collection. In the collection of ebony Makonde sculptures, many had been bought to decorate their homes – such as the figure of the Makond-ised saint in the first photograph card. As for the exterior, a composite architecture similarly mirrored the spectrum of the colonial inventory. The opposition and resistance to the colonial system were absent, they would be controlled by co-opting ›assimilated‹ individuals into ›white‹ civilisation. However, it was necessary to imagine the members of the ›pre-assimilated‹ culture, since they were being modified by the ›superior‹ European culture. In light of the evidence of change, the fiction of ›tradition‹ was supported by museographic and scientific tools (even if amateur). The dissociation of the bodies and the objects took root. The Makonde sculptors’ work was catalogued and studied inside the museum’s building, while in the square behind the museum, the workers of this ›local culture‹ were made to correspond to an ethnographic context that was suitable for their ›cultural cycle‹.

Margot and Jorge Dias visited the Nampula Museum in 1958 with a mixture of interest and disquiet. In 1961, in order to compile material for the fifth volume of Os Macondes de Moçambique, they commissioned a professional photographic inventory from the Mozambique Institute for Scientific Research in Lourenço Marques. The request consisted of surveying collections of Makonde art in Mozambican museums, resulting in 4 boxes of photographs, where 225 photographs corresponded to the collection at the Nampula Museum and 37 corresponded to the ethnographic section of the Museum of Natural History situated in Lourenço Marques, which is today Maputo, the capital city of Mozambique. Nowadays, these 4 boxes of photographs are located at the Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig, Germany.

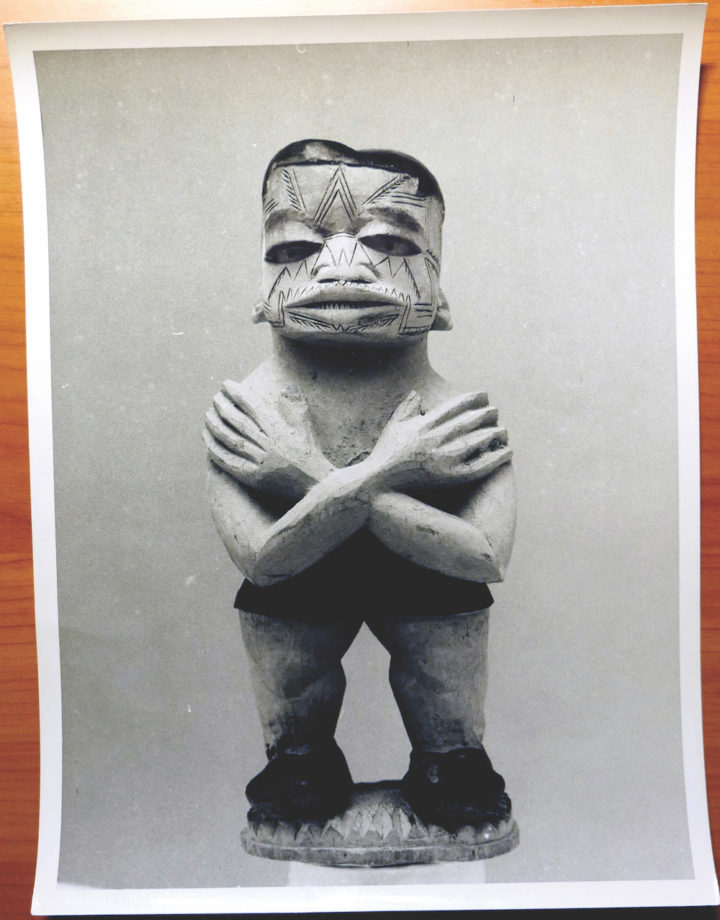

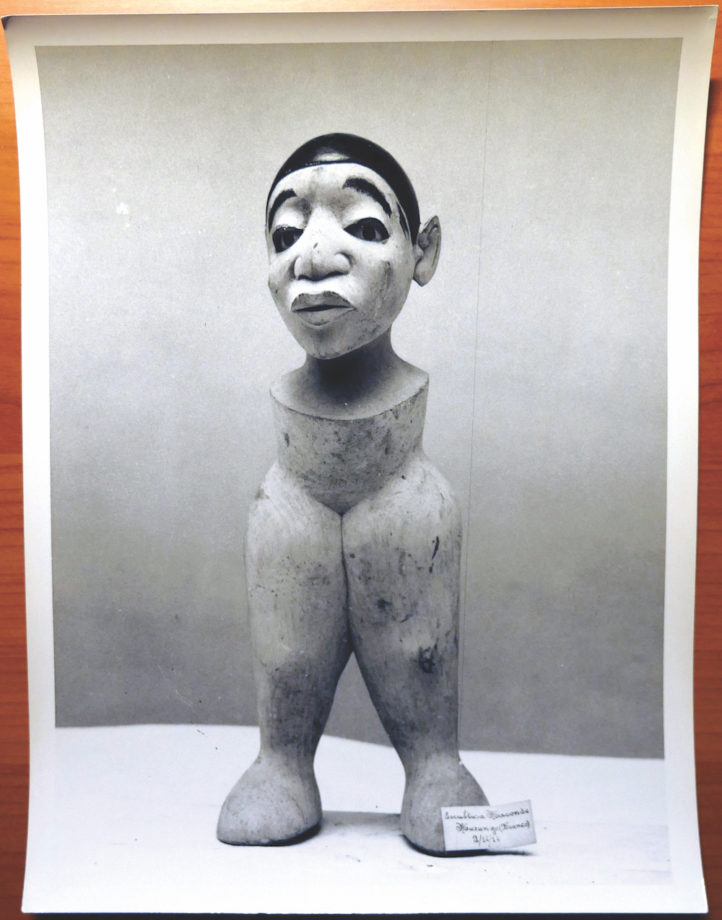

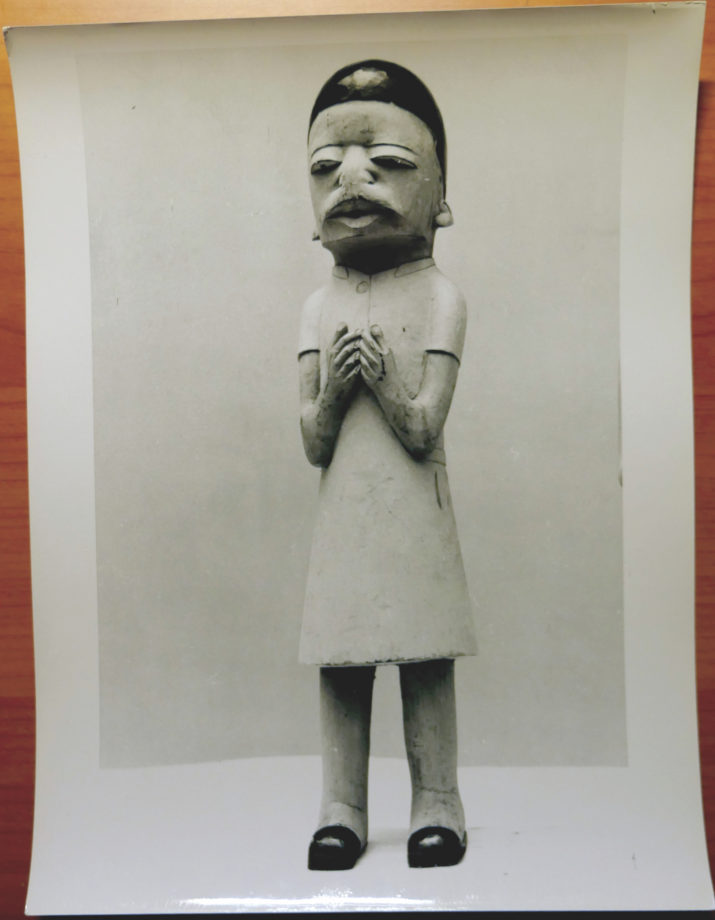

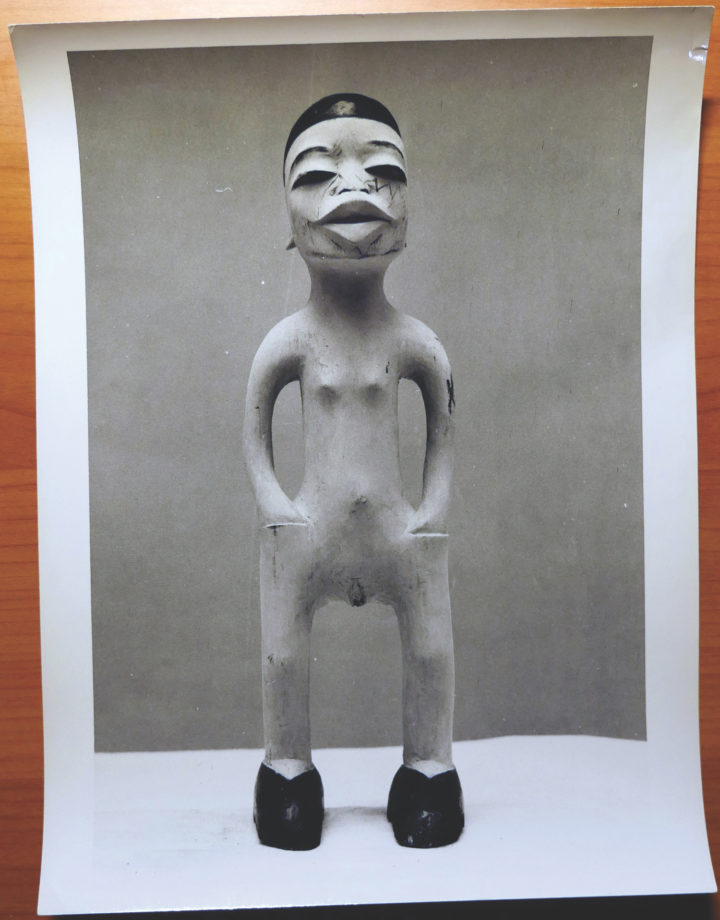

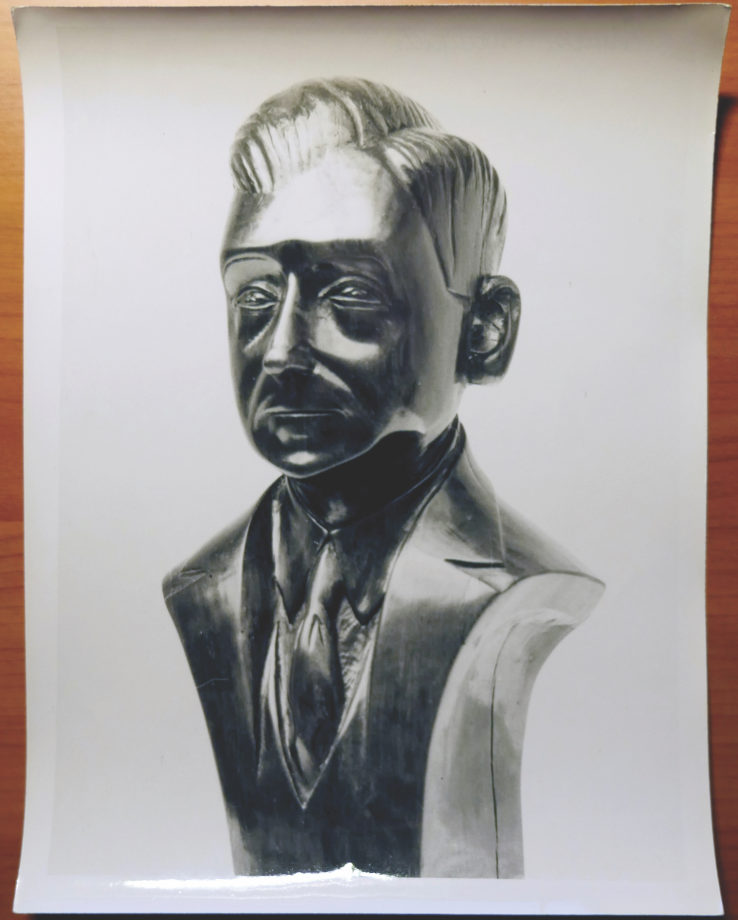

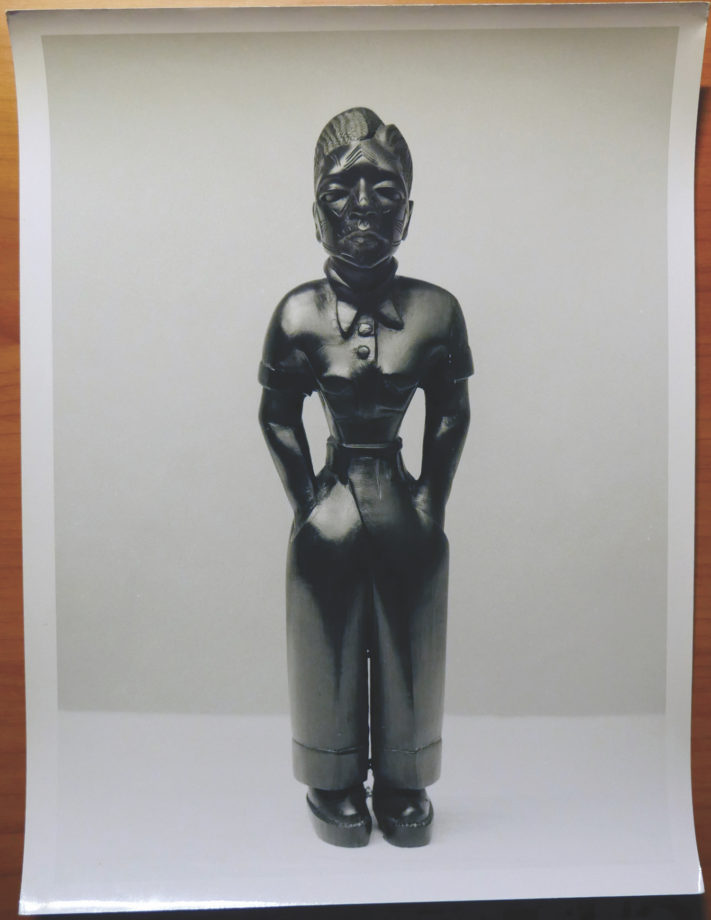

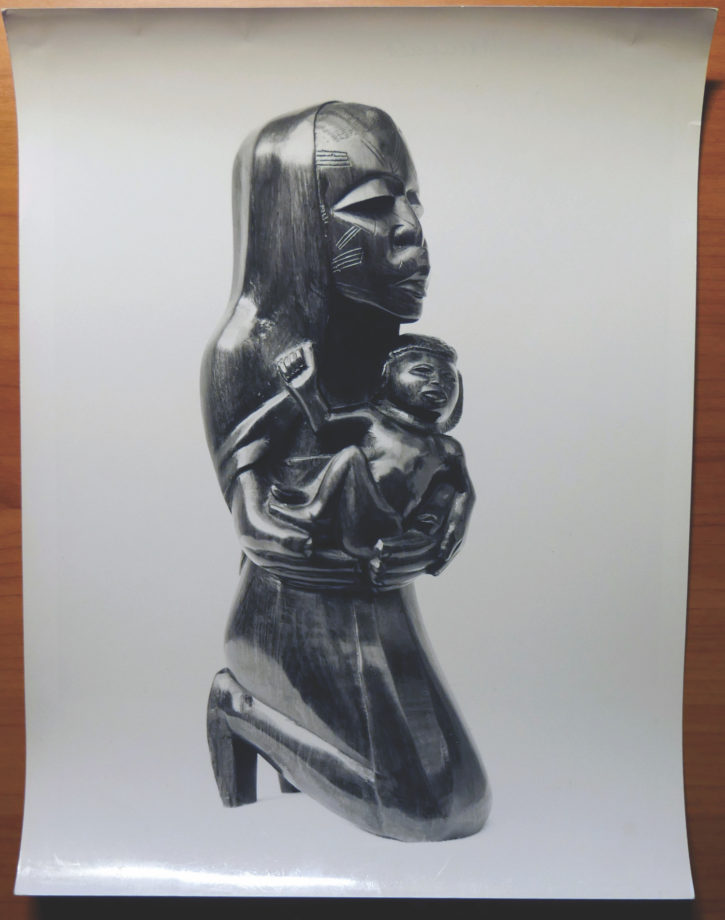

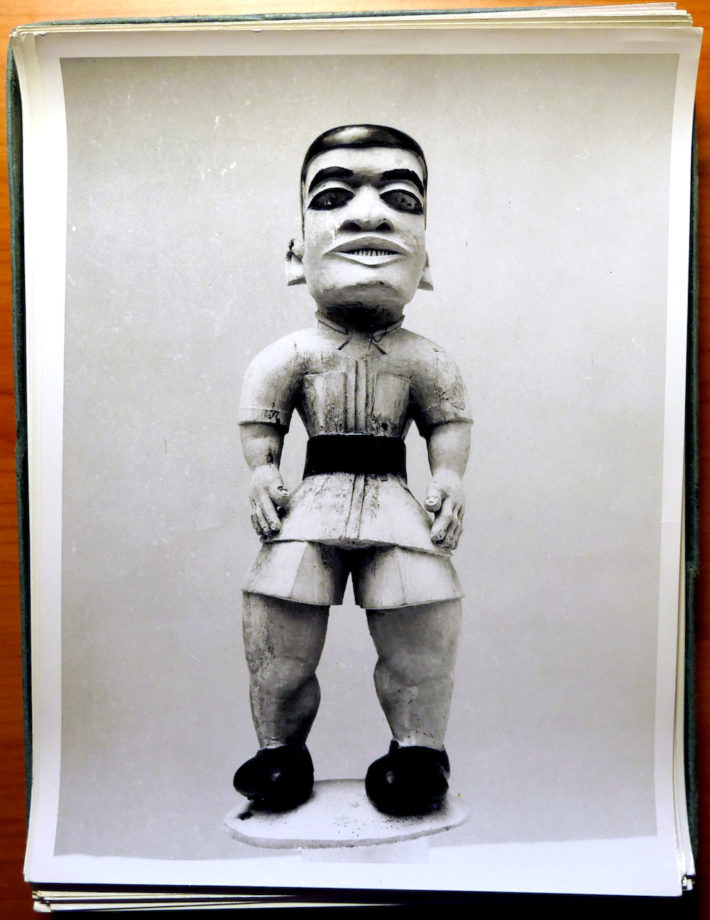

Fig. 15–18; 19–22, 23–24: Selection of photographs: Makonde sculpture, from the collection of the Nampula Regional Museum of Ethnology, 1961. Photographs credited to Manoel Manarte (Head of the Photographic Department of Mozambique Institute for Scientific Research), 18×24 cm. Nampula, Mozambique. Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig.

Photographs from the collection that Margot Dias gave to Giselher Blesse, in 1991. Unknown photographer (Mozambique Institute for Scientific Research), Leipzig (2019) – recently, it was possible to prove that these photographs were taken by an ›African‹ and ›assimilated‹ photographer working for this Institute.

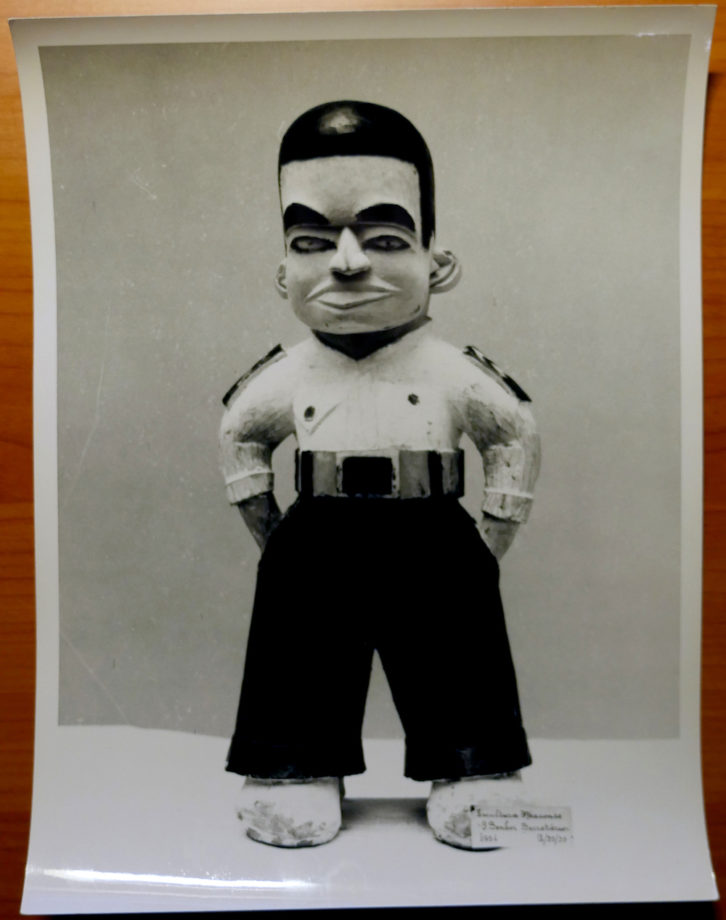

The indices in the search engines of public libraries in Germany constantly bring up the prefix Ost in publications associated with the word Mozambique: Ost, German for east, as in Ostafrika and Ostdeutschland. In early 2018, my research work during my artistic residence at the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig[11],concerned the relations between Mozambique and the former GDR. One of my inquiries was, whether historical materialism has had an application in exhibitions, particularly those that made use of the museum’s colonial collections. In 1977, Giselher Blesse, the curator responsible for the East Africa and South Africa collections at the Leipzig Museum, prepared his first exhibition, bringing together contemporary art from Mozambique and Makonde objects from the museum’s colonial collection. The exhibition was called Mosambik: Kunst und Handwerk einer jungen Volksrepublik [Mozambique: Arts and Crafts of a young Peoples’ Republic]. When I interviewed him, Blesse affirmed that the theoretical justification for the exhibition was a key question that needed to be resolved. One operated within the notions of base and superstructure, using an adaptation of the German Kulturkreislehre (especially the variant of Hermann Baumann). Within this theoretical alignment, the exhibition narrated the ›culture and way of life‹, interrelating religion and society. At the Leipzig Museum, I found the reference to the 4 boxes with the photographs of the Makonde art from Mozambique. The black and white photographs showed a sequence of Makonde art figures that brilliantly caricatured the ›white‹ Portuguese colonisers.

In addition to the caricature, other pieces were faithful ebony wood representations of figures from Portuguese history and literature, such as Salazar[12] and Luís Vaz de Camões.[13] Yet others showed Makonde figures incorporating signs, gestures, and attire from the colonising culture. In 1991, after the political transformation of Germany, Giselher Blesse came to Lisbon to meet Margot Dias, with whom he had corresponded years before. While preparing the 5th volume, Margot Dias asked the Leipzig Museum for information on the Makonde masks and sculptures in the collection of the German anthropologist Karl Weule – who had also once been the director of that Museum. This collection originated from his expedition to southern Tanzania in 1906, when this region was still a German protectorate. As for the 4 boxes with photographs of Makonde sculptures from Mozambique, they were of little use to Margot Dias, since they could not be categorized as either ›traditional‹ art nor as so-called ›modern‹ Makonde art. Blesse was interested in precisely this phase of the transformation of Makonde art that was linked to religious and social phenomena toward so-called modern art, even if it was disconnected from these representations (see Branco/Simão 2021). The project for the 5th volume would not have included these photographs – unless Blesse were to pursue the project. The boxes were given to him and, in his turn, Blesse donated them to the Leipzig Museum. Generically considered to be ›commissioned art‹, the disconcerting critical expression of some of these pieces, the sarcasm, and the humour offer resistance to the strict cataloguing of this collection. The Makonde collection at the Nampula Museum could have been challenging the colonists from the heart of their power apparatus (the museum) – in any case, it demonstrates a paradoxical repertoire of coloniality that is fundamentally rooted in a perception of itself.

Defunct Context

With regard to the exhibition and the workshop held at the Witswatersrand University Museum of Anthropology, I was essentially interested in presenting an ›evolution‹ of the representations – as opposed to the year 1959 – in ways of viewing objects and in the system that they are a part of, irrespective of whether it related to works of art, human remains, or archive documents.

This was facilitated by one attribute in particular, which was provided by the environment of the Wits Museum itself: the fact that this museum had been divested of its ethnographic collection. Effectively, the anthropology museum today is engaged in a programme of debates on the »defunct context«, a term coined by its director, George Mahashe, to announce the museum in the absence of »artefacts of the Bantu peoples«, which had once filled its halls and display cabinets. The concrete experience of this museum without objects provided a real safe environment, in which to examine the work of Jorge Dias. Free from the effect of this tutelary weight (as well as the authority of the archives), these photographic materials were taken much closer to the strata, from which the subjects in this photographic collection originated.

My presentation was hosted as part of a defunct metaphor that served to approach the post-representational question of museological contexts. In the final part of my presentation, I showed the set of black and white photographs, that I had recovered through my research at the Leipzig Museum and which represented the Makonde collection at the Nampula Museum in 1961. Surprisingly, the audience at the workshop reacted to these photographs with loud guffaws. The force and beauty of this reaction strengthened my resolve to pursue this research, in order to show these images at an opportune moment to an audience in Portugal. This happened a few months later, on 14 June 2019 in Porto, in the context of the Reframing the Archive workshop, organised by the Archivo Platform. This event was held in a building that had once been the prison and court of appeals in Porto, which is currently the Portuguese Centre for Photography. As I suspected, presenting the photographs to a Portuguese audience did not elicit even a smile, but only resulted in a deep and uncomfortable silence.

On 26 January 2020, an exhibition was inaugurated at the Galeria Avenida da Índia – an avenue with a colonial name – that brought together a significant part of my artistic work linked to the Mozambique archives. With the portmanteau R-Humor, which I chose as the title, the exhibition heralded a specific way of inventorying the 26 pieces that comprised the display. This decade-long approach to my work was the result of a reflection on the challenges that I faced working with archives at different forms of incompleteness. The exhibition urged one to reimagine archives through the forms of absence therein: deferred strategies, temporary restrictions and public secrets, such as rumour or humour, as unsuspected proof of the clairvoyance of reality. Using a device that I called the mirror-wall, the exhibition consisted of a central piece made up of a composition of blown-up photographs depicting the old collection of Makonde art at the Nampula Museum. Facing this mirror-wall, the R-Humor exhibition juxtaposed excerpts from the Mozambican film Mueda, Memória e Massacre (1979–80), by Ruy Guerra, where the representation of the ›Other‹ entails an equally paradoxical affectation. In the case of this film by Ruy Guerra, Mozambican actors play the role of the ›whites‹, very often ridiculing them and causing guffaws amid the audience. There is no distancing among an oppressed population, because colonisers penetrate their lives and offer no respite, thus representation takes place in another way, by means of incorporation, by means of a change, an appropriation that is transformed. This exhibition did not present the conclusions of any research. On the contrary, it was a hybrid space, even if partially representative, but open to a procedural dimension. The archive was no longer used to represent, becoming a moment of practising the tradition of representing, with its particularities, since it chose a suspended programme. Equally in suspense was its final determination, as an artistic or political practice – it is the context to which the production is linked, that dictates the assimilation, or not, of one form by the other.

Fig. 25: LISBON

Translation from Portuguese: Roopanjali Roy.

The print version of this text is published in the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, issue “The Post/Colonial Museum”, 2022, p. 167-201. In order to make the issue “The Post/Colonial Museum” available to a wide readership, specifically on the African continent, we decided to use the long standing collaboration between boasblogs and the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften to successively publish all contributions in print and online (as DCNtR debate). We thank the editorial boards of both, the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften and the boasblogs, as much as the publishing house transcript for embarking on this project together. Furthermore, our thanks go to the participants of the conference on Museum Collections in Motion, which was generously supported by the Global South Studies Center, University of Cologne, the research platform “Worlds of Contradictions”, University of Bremen, the Museumsgesellschaft of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Most of all, we thank the contributors to this debate for four years of exchange, debate and intellectual companionship.

Footnotes

[1]Jorge Dias had a degree in Germanic Philology from the University of Coimbra. He did his lectureship between 1938 and 1947 at the universities of Rostock, Munich, Berlin, Santiago de Compostela, and Madrid. From his experience at German universities he absorbed and developed the anthropological disciplines that resulted, in March 1944, in his doctorate at the University of Munich in the area of philosophy, as well as Volkskunde.

[2]The ethnographic films of Margot Dias have been edited on DVD in a co-edition of the Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema/National Museum of Ethnology of Lisbon (Costa/Da Costa 2016).

[3]It was only possible to work with these documents thanks to the availability and courtesy of the following people and entities (in the order in which they appear in the essay): João Pedro George, from the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon, Harry G. West, Ruy Guerra, Bernhard Guttsche, and Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig.

[4]Scholars have recreated the history of the documentation of the Nampula Museum (a mix of family and museum archives) and the way it arrived intact in Lisbon a few years before Mozambique’s independence.

[5]The workshop Critical Entanglements: Colonialism, Anthropology and the Visual Arts and the exhibition Ethnographically Intimate were organised jointly with Dr. Caio Simões Araújo, a postdoc researcher at CISA, and the director of the Museum of Anthropology, George Mahashe, the South African artist and academic. The events were held on 10–11 May 2019, at the Wits University Museum of Anthropology.

[6]Jorge Dias (1961a): Portuguese Contribution to Cultural Anthropology. Contents: 1) A Historic Introduction to Portuguese Anthropology; 2) The Makonde People: History, Environment and Economy; 3) The Makonde People: Social Life; 4) Portugal: Land and People; 5) Community Studies in Portugal; 6) The Portuguese Abroad.

[7]Although it is difficult to determine a precise date, according to Professor Yussuf Adam (UEM) the confidential reports Jorge Dias prepared appeared at the Centre for African Studies and the Mozambique Institute for Scientific Research through Aquino de Bragança.

[8]The 4th year of the mission only continued in 1961. The Ministry for Overseas Affairs did not authorise the 1960 campaign, for fear of the political turmoil that ended up in the incident that became known as the Mueda Massacre, which took place in the town of Mueda, on 16 June 1960.

[9]FRELIMO stands for Mozambique Liberation Front and was created in 1962 in Dar es Salaam as the result of the merger of the three main anti-colonial movements that since ever since the 1950s had been organizing acts of resistance against the presence of the Portuguese in Mozambique.

[10]RENAMO stands for Mozambican National Resistance. It was a political organisation in Mozambique, that was initially sponsored by Rhodesian intelligence. Created in 1975, RENAMO was part of the anti-communist movement in opposition to the ruling FRELIMO party. The movement had its roots in a group of anti-FRELIMO dissidents who emerged immediately before and shortly after Mozambican independence.

[11] The residency at the Grassi Museum took place during 2018 and was hosted by director Nanette Snoep. This residency was part of the project Exodus Seasons #4, organised by curator Marta Jecu.

[12]Antônio de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970) was a prominent figure of the Portuguese colonial-fascist dictatorship, he dominated Portuguese politics for more than 40 years.

[13]Luís Vaz de Camões (Lisbon, c., 1524 – Lisbon, 1579 or 1580) was a portuguese poet. He is considered one of the main authors of classical Portuguese literature and the mythical narrator of Portugal in its »expansionista awakening«.

References

Branco, Jorge Freitas/Simão, Catarina (2021): »About the 4 Photo Boxes of Margot Dias – Interview to Giselher Blesse«. In: Direito à Informação/Right to Information, ed. by Catarina Simão, Lisbon: Galerias Municipais/EGEAC, 68–82.

Costa, Catarina Alves/Da Costa, Paulo Ferreira (2016): Margot Dias: Ethnographic Films 1958–1961, Lisbon: Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema/National Museum of Ethnology of Lisbon.

Dias, Jorge (1961a): Portuguese Contribution to Cultural Anthropology, Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Dias, Jorge (1961b): »Conflitos de Cultura«. In: Estudos de Ciências Políticas e Sociais 51, Lisbon: Separata de Colóquios sobre Problemas Humanos nas Regiões Tropicais, 109– 125.

Dias, Jorge (1964): Os Macondes de Moçambique. Aspectos Históricos e Económicos, vol. I, Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

Dias, Jorge/Dias, Margot (1964): Os Macondes de Moçambique. Cultura Material, vol. II, Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

Dias, Jorge/Dias, Margot (1970): Os Macondes de Moçambique. Vida Social e Ritual, vol. III, Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

Guerreiro, Manuel Viegas (1966): Os Macondes de Moçambique. Sabedoria, Língua, Liter- atura e Jogos, vol. IV, Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

Vicente, Filipa/George, João Pedro (2021): »Family Colonialism: The Nampula Museum Archive«. In: Direito à Informação/Right to Information, Catarina Simão, Lisbon: Galerias Municipais/EGEAC, 84–101.

West, Harry (2006): »Invertendo a Bossa do Camelo. Jorge Dias, a sua Mulher, o Intérprete e Eu«. In: Portugal Não é um País Pequeno. Contar o »Império« na Pós-Colonialidade, ed. by Manuela Ribeiro Sanches (org.), Lisbon: Livros Cotovia, 141–190.