Collecting on Women in Gabon during the Colonial Period:

The Case of the Akure Metal Necklaces

Akure necklace. ETHAF 023109: © Johnathan Watts. Musée d’ethnographie de Genève.

Ethnographic collections are seldom analyzed in terms of gender, yet this prism of analysis allows for a renewed consideration of collections that have often been viewed almost exclusively in masculine terms. By focusing on a corpus of metal necklaces, often referred to as torque[1] in the inventories, this paper sheds light on a particular aspect of the history of ethnographic collecting with regards to women: the collecting on women.

Etymologically, the word torque comes from the latin verb torquere, a verb that has both a literal and a figurative sense[2]. Literally, torquere means “to bend”, while figuratively, it means “to torture”. In Gabon, where they were created and worn, they were called akure[3].

The rich archives and drawings of the Alsacian missionary, Fernand Grébert, stationed in Gabon for 20 years, provide a wealth of information on akure’s presence, use, collecting practices and museal acquisition. Indeed, by intersecting the museum entries of akure in the collections with Grébert’s records who sold hundreds of material culture items, including akure, to the two ethnographic museums of Romandie[4], the Museum of Ethnography of Geneva (MEG) and the Museum of Ethnography of Neuchâtel (MEN), this paper highlights the practice of akure collecting and discusses what it implies for women being collected on.

Akure are bended metal necklaces that were collected in Gabon, since the 19th century and are common in European museums ‘collections, including the MEG’s and the MEN’s. More or less 10 akure can be found in each museums’ database, the majority of which were bought to Fernand Grébert. Many missionaries have combined their fieldwork with ethnographic practices such as written descriptions, audiovisual records and collecting, becoming “crucial producers of cultural practices, knowledge, and texts in the particular locations where they worked” (Cinnamon, 2006:1). It is the case of Grébert, who stationed in Gabon as part of the Evangelical Missionary Society of Paris between 1913 and 1931.

He produced thousands of drawings, a richly illustrated monography, several books, playing cards, articles, conferences, and collected an extensive amount of material culture, including the akure, that he sold to the MEN and MEG between the 1920s and 1950s. The extensively documented archives of Fernand Grébert, especially through his drawings, can be connected to the museum collections created consequently, in order to understand the practices associated with collecting akure; practices that illustrate how both sense of the word torquere are relevant in this case.

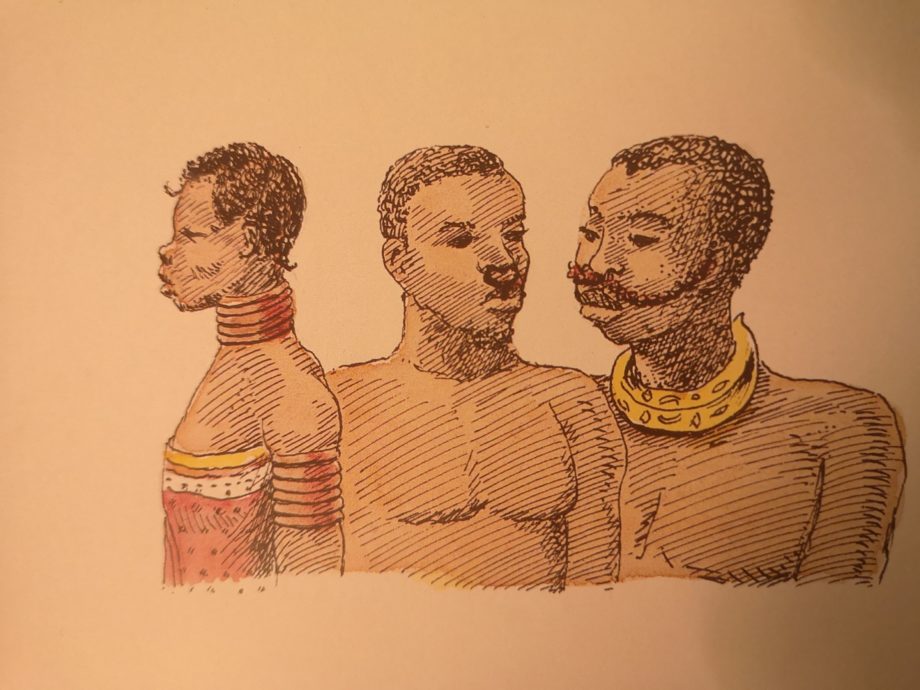

Drawing by Fernand Grébert. Folio 301 “Le Gabon de Grébert de 1913 à 1932”.

Two types of heavy akure were described in Grébert’s drawings (folio 198)[5] and can be found in the collections. In his albums that depict not only his journey to Gabon, but also all aspects of Gabon, the people and customs, the fauna, flora and material culture, akure are clearly drawn and recognizable in museum online databases. They are drawn alongside forgings (folio 93); worn by women fully adorned or in simple attire (folio 143, 220) or depicted within scenes (folio 191, 280, 301). They are thick adorned pieces of circular brass or copper (rarely iron) with an opening in the back that were worn by ekang[6] (fang-betsi) women but also men. Weighing on average from 1 to 2 kg a piece, these metal necklaces are either plain or decorated with finely incised geometric symbols that can also be found on sculptures, and everlasting body adornments such as tatoos or scarifications. The eternal character of wearing an akure is signified by Grébert in his monography when he describes them as “brass necklaces cast in one piece, and closing on the subject, with a hammer blow, definitively[7]”.

The definitive character of the wearing could be associated with a rite of passage, a change of status within the society. The ethnologist Louis Perrois who has commented on Grébert’s albums, notes that the akure were worn ad vitam eternam by women who were considered within the society (folio 280). Günter Tessman, a German colonial administrator who has produced an important monography on the Fang people in the early 20th century gives a precise account of how these necklaces were put on, the difficulty it implied, the ritual aspect of it, the role and presence of the traditional healer and blacksmith, in what goes beyond wearing a necklace, but undergoing what could be seen as a challenging rite of passage.

When confronted with the akure museum collections today, three elements are to be noted. Firstly, many of these metal necklaces are broken or unbended on one side, indicating a forceful opening of these pieces that were supposed to be kept on for a lifetime. Secondly, several entries show that the breaks are due to the retrieval of the necklaces and most importantly, that the retrieval was done directly on the women.

For instance, the ancient registered entry of the akure inventoried under III.C.294[8] by the MEN indicates that it was: “broken when taken from the neck of the woman who was wearing it”[9]. In Grébert’s second album, folio 301 depicts a man wearing an akure, while the woman drawn next to him is wearing replacement necklaces out of creeper. Grébert specifies why: in fact, the brass necklaces had been sold, by him, and most likely to the museum. The caption of the folio concerning the replacement necklaces and armbands reads: “In replacement of the brass necklaces, resold” (folio 301).

Unbended akure necklace, ETHAF 011688: © Johnathan Watts. Musée d’ethnographie de Genève.

Ornaments serve as signals of status, they are external cues that situate the wearer within the society, indicating marital, hierarchical, or religious status. Their collecting should be understood not only in terms of the objects themselves and how precious, beautiful or culturally relevant they are, but also in terms of the impact of their removal on the status of those dispossessed. In the case of the akure, it is specifically women that seem to have been targeted, and therefore their status within the society might also have been subsequently altered.

Cultural curator and chairperson of the Panafrican Art Association (SANKOFA), Bansoa Sigam is an anthropologist and museologist by training who has worked and conducted research in both the Museums of Ethnography of Geneva, and of Neuchâtel. This Swiss native of Cameroonian descent is currently a double doctoral candidate in art History and cultural geography, her research focuses on the intersection between gender and the history of ethnographic museum collections from Central Africa.

About the DCNtR Debate #1: It has long been accepted that colonialism had a distinctive epistemic dimension, which was upheld by disciplines such as social anthropology and other knowledge-making projects. Under this colonial episteme, people and human experiences were hierarchically classified according to racial categories and ethnography and ethnographic collecting were key components in these processes. However, the colonial regime did not only rely on race as an organising category, but also on gender. The first debate in the DCNtR Debates series tackles this question with seven contributions from around the world which explore the relationship between the gender of the collector, the gender of those collected from and consequences of these gendered practices of collecting for the epistemic practices of display in today’s museums.

Footnotes

[1] In French.

[2] Etienne, G. 1990. Cahier de vocabulaire latin. Liège: Dessain.

[3] In Fang, the entry of the Fang- French dictionary is AKURE (h) n.l, pl. bakure. Collier en cuivre massif des Betsi qui peut peser plusieurs kilos.

[4] Region referring to the French speaking part of Switzerland.

[5] All folio mentioned are published in “Le Gabon de Fernand Grébert de 1913 à 1932”.

[6] Ekang is the self-referential term used by people that all link to the primordial Ekang dynasty. Here Ekang refers to populations described as Fang.

[7] Grébert Fernand, Monographie ethnographique des tribus Fang, Folio 29, Lettre M.

[8] There is no evidence from the collections online that this piece was collected by Fernand Grébert unlike , however other Akure from the MEN’ss collections.

[9] MEN Online collections database: https://webceg.ne.ch/

References

Cinnamon, J. (2006). Missionary Expertise, Social Science, and the Uses of Ethnographic Knowledge in Colonial Gabon. History in Africa, 33, 413-432.

Etienne, G. (1990). Cahier de vocabulaire latin. Liège: Dessain

Galley, S. (1964). Dictionnaire Fang-Français et Français-Fang, suivi d’une grammaire Fang. N.p., 1964. Print.

Grébert, F. (1928). Au Gabon : (Afrique équatoriale française). 2e éd. Paris: Soc. des Missions évangéliques.

Grébert, F, and Pittard E. (1940). Monographie ethnographique des tribus fang : Bantous de la forêt du Gabon, Afrique équatoriale française : documents réunis de 1913 à 1931. Genève: [éditeur non identifié].

Grébert, F., Savary C., and Perrois L. (2003). Le Gabon de Fernand Grébert : 1913-1932. Genève: Musée d’ethnographie.

Laburthe-Tolra, P., Tessmann, G., Falgayrettes-Leveau C. (1991). Fang. Paris: Editions Dapper.