Archives Research on Chinese Government’s Preparation for the 1935 Royal Academy International Exhibition of Chinese Art

DCNtR Debate #2. Thinking About the Archive & Provenance Research

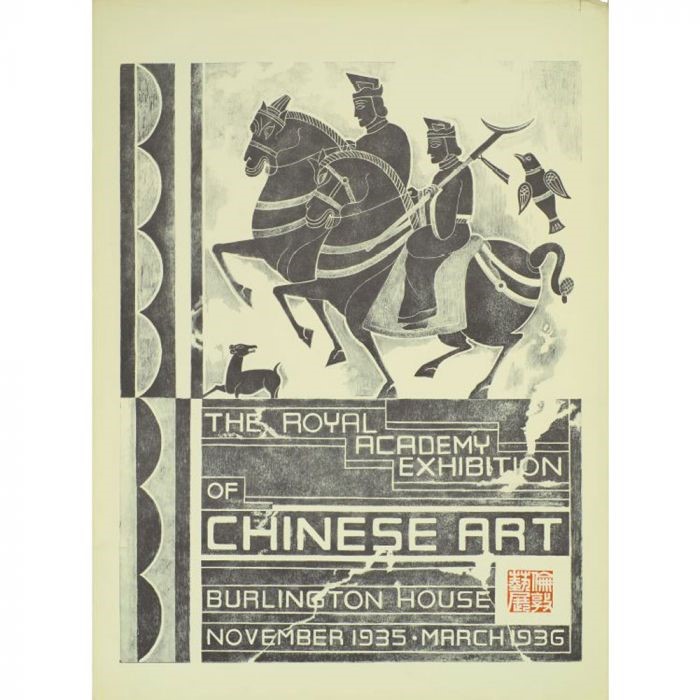

Fig. 1. The Poster of the 1935 International Exhibition of Chinese Art. Courtesy to the Royal Academy of Arts.

The International Exhibition of Chinese Art (hereinafter 1935 Exhibition) was held at Burlington House, London, from 28 November 1935 to 6 March 1936.[1] As “one of a sequence of national art shows” at the Royal Academy of Arts (hereinafter RA) and the annual winter exhibition of the RA, 3,078 Chinese artworks in all genres lent by 246 public and private collections from fifteen countries were displayed together under one roof for nearly four months, which made it the largest cultural event of its kind ever mounted.[2] The exhibition was well received in Britain and internationally and made a profit.[3] Nearly 420,000 visitors saw this exhibition, including many noble people and celebrities from around the world, including the King and Queen of Britain, the Crown Prince of Sweden, the Chinese Ambassador to Britain Guo Taiqi (郭泰祺, aka Quo Tai-chi), the Special Commissioner of the Government of China Dr Zheng Tianxi (郑天锡, aka F. T. Cheng), etc.[4] As a consequence, the 1935 Exhibition demonstrated Britain’s network with the world, pushed the “Chinese fashion” in the West to its climax, “raised an unprecedented degree of interest in Chinese art and culture” that lasted for decades, and became a benchmark for evaluating succeeding exhibitions of Chinese art, and eventually revolutionized Chinese art history as an intellectual discipline.[5]

For China, the 1935 Exhibition also enjoyed remarkable significance. It was the first time that Chinese national treasures were going overseas, and the first that the Chinese government sponsored an exhibition outside China. The exhibition consisted of 1,022 artworks, including 735 from the National Palace Museums Peiping (today’s Beijing), accounting one third of the total number. They embodied the finest level of Chinese civilisation, and demonstrated the willingness of the Chinese Government to collaborate with other countries via the allure of national culture. Along with other artistic and cultural events that the Chinese government supported in the same period, this exhibition became a “manifesto” of Chinese civilization and has caused a strong sensation in the West.

Scholarly interest for the 1935 Exhibition has grown internationally in the last fifteen years, revolving around the artistic, historical, cultural, political, national and international dimensions of the event.[6] There are two main topics in my study: the political engagement during the exhibition and the mobility of the artworks sent by the Chinese government during and after the 1935 Exhibition. The first purpose of my research is to understand the socialisation and the cultural diplomacy of China in the overlapping context of the 1930s. Studying Chinese art collections and exhibitions outside China illuminates the fascinating history of the international engagement with China and Chinese objects, which developed over time in different ways. The display strategies at the museums and the cultural policies reflect the national power and politics of China domestically and internationally. Secondly, the transportation of the artworks to London was a complicated process, causing chaotic debate among Chinese intellectuals on the conservation and repatriation of Chinese cultural relics mixing with sentiments of patriotism and nationalism. The relocation of the artworks to Taiwan was a result of the retreat of the Nationalist Party and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China after the Civil War in 1949. The situation of two National Palace Museums between the Strait poses a challenge for the definition of Chinese art and raises potential problems of art repatriation and restitution.[7]

The archive of the 1935 Exhibition in the RA Library is extensive, consisting of (1) manuscripts of meeting minutes of the Exhibition Committee from December 1934 to March 1936; (2) the annual report of the RA; (3) five volumes of press cuttings concerning on the Exhibition between 1935 and 1939 from Britain, China, and European countries in the respective languages, but none in Chinese; (4) ten folders of official and legal documents, correspondence and telegraphs among the Committee members in Britain and China, and letters from visitors to the exhibition and their replies; (5) two albums of photographs showing the packaging, transporting and installing of the artworks, and the gallery views of the Exhibition, and (6) some albums of photographs of individual exhibits.[8]

Fig. 2-3: Working with archives in the Royal Academy Library. Photographs by the author..

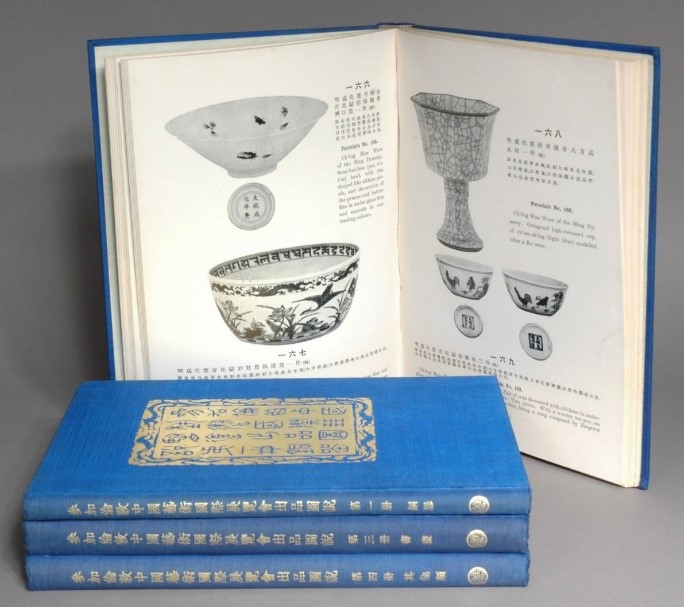

Fig. 4-5: Catalogues of the Exhibition from Britain and China. Courtesy of biblio.com.

Other materials that I consulted include The Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art and the Illustrated Supplement published by the RA and the Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Government Exhibits for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London published by The Commercial Press under the commission of the Government of China. The latter catalogued the artworks that participated in the Shanghai Pre-Exhibition from 8 April to 5 May 1935 in four categories: bronzes, porcelain, painting and calligraphy, and miscellaneous. The archivist of the Second Historical Archives of China (Nanjing), Liu Nannan (刘楠楠), compiled the official documents and correspondence between the Chinese Preparatory Committee and the Government of China in regard to the exhibition, which provides a Chinese perspective on the exhibition’s organisation and administration, and the cooperation with the British Government. What is more, writings and memoirs by the actors in the Exhibition provide some personal accounts and intimate interpretations to understand the event and historical contexts.

As the historical details unfolded in front of my eyes, I was fascinated by the exquisiteness of artisanship of all the Chinese artworks in the exhibition, and impressed by the story of every participants to this international Chinese art festival, and touched the spirit of cooperation and compromise between the two countries that eventually “turned internationalism from a utopia to a concrete and visible reality”.[9] However, due to the word limit, this paper, drawing on the archives, I mainly focus on the endeavour made by the Chinese Committee and Chinese government during the preparation of the 1935 Exhibition, collaborating with their British counterparts and connecting China to the world.

First of all, the 1935 Exhibition was much-anticipated in China. In the 1930s, China experienced some industrialisation and enlightenment of nationalism. China’s international status had improved to some extent since China had been an ally in WWI. However, it was still a subject to Western imperialism and suffered setbacks from conflicts between the Nationalist government in Nanjing, the Communist Party, remaining warlords, and Japan after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Confronting the chaos of the early twentieth century, the young Republic of China adopted the new cultural diplomacy to seize upon culture of the old Chinese civilisation to humanise Chinese in the West, seeking for opportunities to demonstrate the world the “new face” of China.

On the other hand, despite the xenophobic views towards China so prevalent in the early-twentieth-century Europe, there were still groups of collectors and academics promoting Chinese art.[10]> The idea of having a comprehensive exhibition of Chinese art in Britain to promote the international appropriation of it emerged as early as 1932, proposed by a group of advanced British collectors of Chinese art. Among them were the British collector Sir Percival David (Fig. 6) who worked in the National Palace Museum as a consultant to the porcelain from Song to Ming Dynasties in 1928. He travelled to China in 1932 and determined to “bring to London some of the very pieces he had helped to put on display in the Forbidden City, as well as those from the many other countries so eager to participate”.[11]

The National Palace Museum in Peiping was established on the National Day of the Republic of China, 10 October 1925. Under the threat of the Japanese invasion, the Museum collection was evacuated and moved to Shanghai in 1933.[12] When the French sinologist Paul Pelliot heard this news, he, who failed to examine the Museum collection earlier due to the outbreak of Sino-Japan War, suggested the British Government to invite China to send the collection to England for exhibition so that Western scholars and collectors could see the treasures in person.[13]

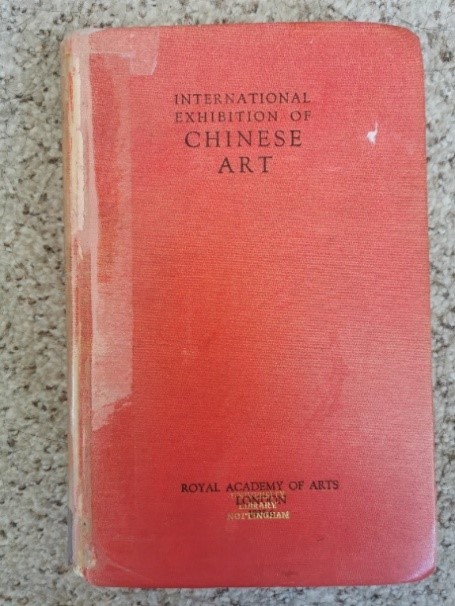

Fig. 6: Chinese and British staff unpack the Chinese national treasures for the exhibition, September 1935. From left to right: Walter Lamb, Secretary of the RA; Zhuang Shangyan (庄尚严, aka Chuang Shang-Yen), secretary accompanying artworks from China; Zheng Tianxi; Percival David; unknown Chinese staff, Chen Weicheng (陈维诚, aka W.C. Chen, counsellor of the Chinese Embassy), Tang Xifen (唐惜芬, aka Tang His-Fen), secretary accompanying artworks from China; Fu Zhenlun, Chinese exhibition assistant. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts..

The formal discussion on the 1935 Exhibition started in 1934.[14] In June, it was proposed to have an exhibition of Chinese art at the RA, ‘for which the Chinese government had already privately agreed to loan work.’[15] The reasons to do so, according to Guo, were “to foster Sino-British relations, exchange two cultures, promote art and celebrate the anniversary of the coronation of the King”.[16] Four months later, this idea was refined by Chinese Minster of Education, Wang Shijie (王世杰, aka Wang Shih-chieh) in a report enclosed to an official letter to the Executive Yuan of the Chinese government. As he stated, inspired by the financial and diplomatic success of the Exhibition of Italian Art, Chinese authorities held very high expectations that this event would demonstrate the grandeur of the Chinese nation to the world and earn support from the West.

…the previous Italian Art Exhibition benefited a lot, so that the previous misunderstandings between Britain and Italy were eliminated, the two countries became friends. The Italian Prime Minister Mussolini had allowed 20,000 pounds to finance the exhibition, but the fund remained unspent until the end of the exhibition and a profit of 37,000 pounds (over 700,000 Chinese yuan) was made. This is the first time that the treasures of our national art and culture have been presented on an international scale in Europe. The benefits to China’s international perceptions and China-British relations will be great. The author expects that the success of this exhibition will be equal, if not greater, than those of previous exhibitions of European arts.[17]

When China was invited to the 1935 Exhibition, it provided the Chinese Nationalist government “an opportunity to demonstrate – and possibly enhance – its authority over China’s national treasures”.[18 ]What is more, the success that the English-spoken Chinese opera Lady Precious Stream (王宝钏传) by Xiong Shiyi (熊式一, aka Hsiung Shih-I) earned at its premiere in London on 27 November 1934 also exemplified the appeal of the ancient and remote civilization to its western audience.[19] It also reinforced the determination of China to hold an exhibition of its national art in London. The whole process of the preparation of the exhibition was staged by the Government of China to demonstrate its authority over the national treasures, its willingness to participate in international affairs, and furthermore, its legitimacy to rule all Chinese territory.

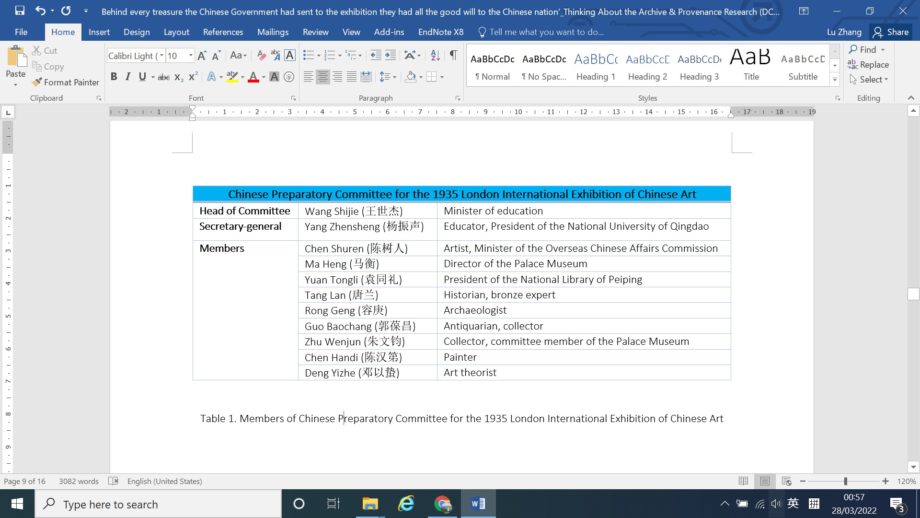

Table 1. Members of Chinese Preparatory Committee for the 1935 London International Exhibition of Chinese Art.

The Chinese Preparatory Committee of the 1935 Exhibition was appointed by the Executive Yuan in November with representatives in administration, art, academics and education (Table 1).[20] Almost at the same time, the British Committee was founded at the RA with a group of prominent people from international backgrounds who shared an interest in Chinese art.[21] Guo Taiqi and Zheng Tianxi were enlisted as the representatives of China. The staffing arrangement put China and Britain on an equal position, which was a great honor for the Chinese government, which has been discriminated against in its international relations. Some Chinese scholar attributed this concession by Britain to the considerable expected financial profit of the exhibition.[22]> Notwithstanding, among this heterogeneous group, both state and non-state, national and transnational actors that ‘each distinguished by nationality and yet committed to a common goal’ collaborated together. The exhibition contributed a glamourous celebration of the art and culture of one country in the territory of another.[23] Undoubtedly, without the involvement of both governments, the project could not become a reality.

The importance that the Chinese government attached to the exhibition could also be seen in the packaging and transportation of the artworks. Confronting the debates among the Chinese intellectuals about the legitimacy of the exhibition and concerns about the security of the objects going to Britain, the Chinese Committee requested that the exhibition could only be processed if Britain would be responsible for the safety of the artworks from the point of shipment, a pre-exhibition in Shanghai and post-exhibition in Nanjing would be held to notify the public, and China should reserve the right not to exhibit abroad for artworks of special significances.[24] The packaging of the artworks was a ritual of art. Before being packed into the ninety-three steel-lined cases for the journey to Britain, the artworks were firstly packed in brocade boxes and bags in an exquisite manner for diplomatic protocol and protection purpose.[25]

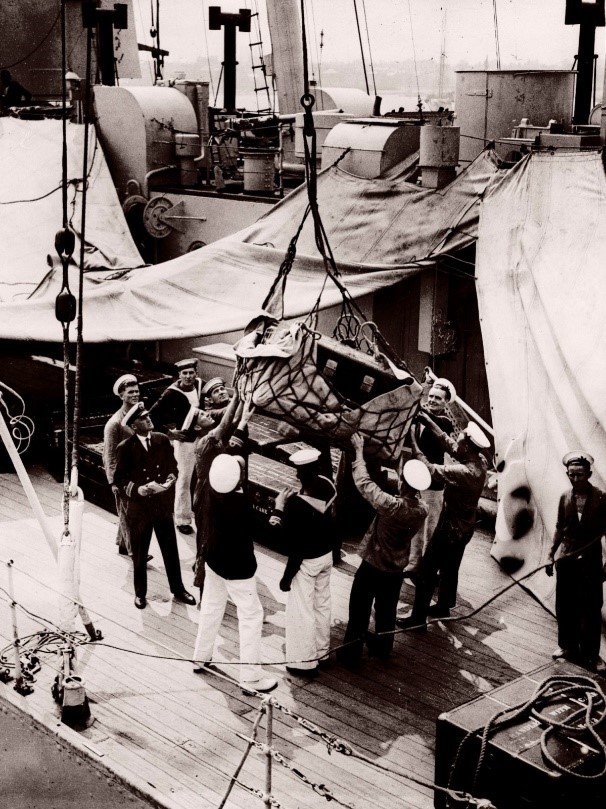

After twenty-eight days, the Chinese artwork on loan from the Chinese Government were put back into the brocade boxes and bags, sealed in ninety-three steel chests, and loaded on the 630-foot-long Country-class heavy cruiser of the Royal Navy H.M.S. Suffolk, getting ready to be transported to the exhibition hall.[26] The transportation was paid by the RA and guarded by the British military. However, to keep the cost down, the artworks from China were not insured.[27] This decision has also been criticized by patriotic Chinese intellectuals.[28] For protection, the Chinese Government appointed Tang Xifen from the Minister of Education and Zhuang Shangyan from the Palace Museum as secretaries accompanying the artworks on board. They examine the chests once every two days.[29] Meanwhile, four exhibition assistants from the National Palace – Fu Zhenlun, Na Zhiliang (那志良), Song Jilong (宋际隆) and Niu Deming (牛德明) – were travelling on another cruise to London. These cases were kept at the warehouse of Burlington House ‘under a close guard’, and would not be unpacked by the British and Chinese Committee members together until the four Chinese assistants arrived in London.[30]

On 25 July 1935, H.M.S. Suffolk finally arrived at Portsmouth. (Fig. 7-8) The arrival of the Chinese art was widely reported and warmly welcomed by local people. [31] These cases that contained “seven-thousand-year civilisation of China” were handled with care by the British soldiers from the ship to four special vans to be transported to London. They were stored in the Burlington House and not unpacked until the Chinese staff arrived. It was also a remarkable moment for China. (Fig. 9) While China used to be a victim of art plundering by the British military in the late nineteenth century, the arrival of the Chinese artworks, with a warship used as a vessel to protect and transport the national treasure of China loaned by the Government of China, marked not only the start of a long celebration of Chinese art in Britain, but more importantly, a new chapter in Sino-British relationships that both the Government of China and Britain anticipated. This time, no plunder, no war, only equality and cooperation.

Fig. 7-8: Hoisting a case from the deck of H.M.S. Suffolk at Portsmouth (left); the crew of H.M.S. Hood unload cases at Portsmouth (right), 25 July 1935. The International Exhibition of Chinese Art at the Royal Academy 1935-6. Photographs by an unknown photographer from Topical Press Agency. Courtesy of the RA..

The unpacking of the Chinese Government loan, conducted by both Chinese and British committees, completed on 19 September (Fig. 6). Two months later, the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, which took years to negotiate and prepare, was finally presented in the galleries of Burlington House. On 3 December 1935, six days after the opening of the exhibition, The Times published “Chinese Art: Complementary to Europe, A Revelation to Britain” to highly praise China’s endeavour to the exhibition and Chinese art as a cultural bridge to link Chinese and British people:

Behind every treasure the Chinese Government had sent to the exhibition, they had all the good will to the Chinese nation… (The good will is) abundantly reciprocated in the enthusiasm of the British public’s response to the manifestation of China’s artistic eminence.[32]

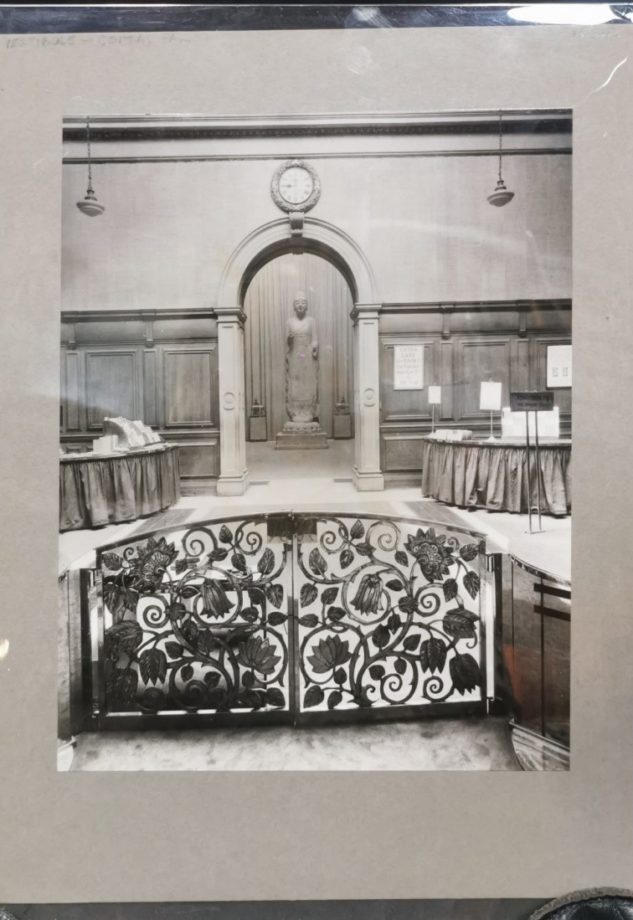

If the escort of Chinese artworks by British warships symbolised the end of Western abuse and plunder of China, then the opening of the boxes containing Chinese national treasures by experts from both countries together materialised a new chapter of Sino-British relationship. The 1935 Exhibition was the largest exhibition that the RA had mounted, and the last exhibition of a foreign national art at the RA before the outbreak of WWII.[33] In this exhibition that embodied Internationalism and celebrated peace and cooperation, the national art of China became a political token in the new Chinese cultural diplomacy that strived hard to promote the new image of China to the world. In the end, exhibiting a venerable and cultured past, it showed that China’s new modern identity would emerge from an enlightened civilization ‘not made with the bayonet, but … founded upon peace, virtue, and affection.’[34] (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9: Welcome to the 1935 International Exhibition of Chinese Art. Entrance to the exhibition. View from the vestibule executed in Firth-Vickers Stainless Steel which was a legacy from the RA’s 1934 British Art Exhibition. Through the arch door is the Central Hall, a six-meter-tall statue of Amitabha Buddha of Sui Dynasty. Royal Academy of Arts Archives.

.

Lu Zhang is a PhD candidate in Art History and a TA at Cultural, Media and Visual Studies, University of Nottingham. She studies the history of collecting and exhibiting Chinese art outside China, the repatriation of Chinese cultural relics, and China-West artistic and cultural exchange since the 19th century. Lu is also a research associate in the Digital Transformation Hub of the Faculty of Arts, University of Nottingham, leading the Archaeology Slide Project, a project to digitalise the photographic archives in the university collection. Lu also works as an art consultant and curator.

Footnotes

[1] My archival research trip to the Royal Academy of Arts is funded by the 2021-22 University of Nottingham Asian Research Institute PRG Funding. I thank Archivist Mr. Mark Pomeroy from the Royal Academy for introducing me to the valuable materials and photographs in regard to the exhibition. I also thank my supervisors Dr Ting Chang and Dr Isobel Elstob for their advice on this paper, and their generous support and help through my PhD journey.

[2] For the exhibition history of foreign national art at the RA, the first one was Spanish painting in 1920. After that, the Exhibition of Flemish and Belgian Art in 1927, the Exhibition of Dutch Art in 1929, the Exhibition of Italian Art in 1930, the Exhibition of Persian Art in 1931, the Exhibition of French art in 1932, and the 1935 Exhibition of Chinese art. For the international lenders of the exhibition, see “Index of Lenders”, Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art 1935-36, 3rd Edition. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1935), xxvii-xxxv.

[3] According to the Royal Academy’s Annual Report, there were 401,768 paying visitors and 2,531 season tickets were sold for the 1935-36 International Chinese Exhibition. The increase in the number of visitors and the figure of 420,000 visitors by the end of the exhibition were continuously reported by newspapers, too. Annual Report for the Council of the Royal Academy to the General Assembly of Academicians and Associates for the Year 1936, (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1937), 23, 40. Also see Jason Steuber, “The Exhibition of Chinese Art at Burlington House, London, 1935-36”, The Burlington Magazine, 148 (1241), (London: The Burlington House Publications, 2006), 528; Ilaria Scaglia, “The Aesthetics of Internationalism: Culture and Politics on Display at the 1935-1936 International Exhibition of Chinese Art”, Journal of World History, Vol. 26, No. 1, (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2016), 105.

[4] Reports about celebrities and famous groups visiting the exhibition were published in newspapers, including the Times and Daily Telegraph. Romanization of Chinese names in this paper are spelt in Pinyin, followed by the original Chinese and another version if applicable in the brackets.

[5] Steuber, 2006, 536. Scaglia, 2016, 106.

[6] Steuber, 2006, 528-36; Ellen Huang, “There and Back Again: Material Objects at the First International Exhibition of Chinese Art in Shanghai, London, and Nanjing, 1935–1936,” in Collecting China: The World, China, and a History of Collecting, ed. Vimalin Rujivacharakul (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011), 138–152; Scaglia, 2016, 103-37. Guo Hui, Writing Chinese Art History in Early Twentieth-Century China, Doctoral Thesis, University of Leiden, 2021.

[7] After the exhibition the artefacts had taken an extraordinary 16-year journey of more than 75,000 kilometers until they had ended up in two different locations separated by miles, a stretch of the South China Sea, and a political divide.

[8] According to the estimate made by Assistant of the Exhibition, George Spendlove, the number of photographs required for the Illustrated Supplement to the exhibition was 2,500. International Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935-36 Publication Committee Meeting Minutes, 7 October, 1935. Royal Academy of Arts Archives, London.

[9] Scaglia, 2016, 137.

[10] Chinese art exhibitions before 1935 included the 1925 Exhibition of Asian Art in Amsterdam organized by the Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (Society of Friends of Asiatic Art), the 1926 Ausstellung Asiatische Kunst Koln (Asian Art Exhibition), the 1929 Exhibition of Chinese Art in Berlin by Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst (East Asian Society). The increasing scales and impacts of the exhibitions suggests a fast increasing interest in Asian and specifically Chinese art and archaeology. See Jason Steuber, 2006, 531. At the same time, modern Chinese artists who studies in Europe also exhibited their artworks. The first large-scale of Chinese modern art exhibition took place in 1933 in Paris. See Stephanie Su, ‘Exhibition as Art Historical Space: The 1933 Chinese Art Exhibition in Paris’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 103, 2021, 125-48.

[11] “Introduction by Lady David”, Rosemary E. Scott, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art: A Guide to the Collection, (London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art & School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1989), 12-13.

[12] Jeannette Shambaugh Elliot, and David Shambaugh, The Odyssey of China’s Imperial Art Treasure, (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2005), 74.

[13] Ta Kung Pao, 20 January 24th year of of the Republic, Page 3. Also see Wu Sue-Ying (吴淑英), “China” in Exhibition: The 1961 Exhibition ‘Chinese Art Treasures’ in the USA as an Example (展览中的“中国”:以1961年中国古艺术品赴美展览为例), Master Dissertation, National Chengchi University, 2002.

[14] Manuscripts of the meeting minutes of Selection Committee of the 1935 Exhibition at the RA are dated from 1 November, 1934 to 10 March 1936. Eighteen out of twenty-one meetings took place before the exhibition, especially in July to October 1935.

[15] Yeh, 2014, 65.

[16] Fu Zhenlun (傅振伦), “The Whole story of the London Chinese Art Exhibition 1 (伦敦中国艺展始末1)”, The Forbidden City (紫禁城), Issue 1, 2004, 147

[17] “谓前次意大利艺术展览会获益甚大,使英、意过去之误会根本消除,两国由是亲善。意首相墨索里尼曾准以二万镑为该会经费,惟展览结果该经费迄未动支,并且获利三万七千磅(合我国币七十余万元)。我国艺术文化之精华在欧洲国际大规模表见此为首次,其于国际观念、中英感情获益必大,比之历次欧洲各国之展览,说者预料此次成功倘非过之,亦当相等。” Wang Shijie, Report on the Status of Preparations for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London (伦敦中国艺术国际展览会筹画近况报告), dated 3 October 1934. Quoted in Liu, 2010, 7.

[18] Scaglia, 2016, 116.

[19] Lady Precious Stream ran for three years in London, which made it the longest running play of the time. For Hsing Shih-I and his career as a playwright and a promoter of Chinese art in the west, see Dianna Yeh, The Happy Hsiungs: Performing China and Struggle for Modernity, (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2014)

[20] The personnel of the Chinese Committee was informed to Britain by telegram on 12 December 1934. See RAA/SEC/24/25/1, Telegram, from Wang Shijie. Also see Scaglia, 2016, 114-5.

[21] Exhibition of Chinese Art 1935-6 Meeting Minutes, November 1, 1934. Royal Academy of Arts Archives, London. Also see Catalogue of International Exhibition of Chinese Art, (London: The Royal Academy of Arts, 1935), viii.

[22] Tao Xiaojun, ‘An Examination of the 1935 London Art Exhibition (1935年伦敦艺展之始末考察)’, Art Observation (美术观察), Issue 20, 2015, 111.

[23] Scaglia, 2016, 114-15.

[24] For the transportation, “如英国政府对于物品之安全,自起运之地点起能负责充分保障,则可赞同。” Official Letter from the Committee of the National Palace Museum Peiping to the Ministry of Education(北平故宫博物院理事会致教育部公函稿), dated 26 May 1934, signed by Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培). Quoted in Liu, 2010, 6. Also see ‘Memorandum from the Royal Academy to H.E. the Chinese Minister’, dated 7 November 1934, signed by Walter Lamb. For the pre- and post- exhibitions, “(一)选送物品运英展览前,应在上海开一预展会,时间拟定明年三月间;物品回国后,并应在南京展览一次,以昭明信。(二)关于特殊重要物品,本会有保留不予出国展览之权。” Letter from the Secretary of the Executive Yuan to the Committee of the National Palace Museum Peiping (行政院秘书处致北平故宫博物院理事会笺函), dated 27 December 1934, signed by Cai Yuanpei. Quoted in Liu, 2010, 9.

[25] Director of the National Palace Museum, Ma Heng (马衡) informed the Executive Yuan via telegraph that the artworks for the 1935 Exhibition “must be put in brocade boxes and bags (须装置锦匣、锦囊)”. Letter from the Secretariat of the Executive Yuan to the Committee of the National Palace Museum Peiping (行政院秘书处致北平故宫博物院理事会函), dated 25 February 1935, signed by Chu Minyi (褚民谊). Ibid.10.

[26] Shanghai Municipal Archives keeps the archives of the Shanghai Pre-Exhibition of the 1935 Exhibition. For an general introduction, see Zhang Yaojun (张姚俊), “The Sensational 1935 Exhibition of National Treasures of the National Palace in Shanghai (1935年轰动上海的故宫国宝珍品展)”, Shanghai Municipal Archives, retrieved on 5 June 2008, https://www.archives.sh.cn/shjy/shzg/201203/t20120313_6385.html, consulted on 29 March 2022.

[27] Letter from the British Committee to Chinese Ambassador, dated 8 June 1934, signed by Geroge Hill, Neill Malcolm, Percival David, George Eumorfopoulos, R. L. Hobson, Oscar Raphal.

[28] “Academics Oppose the Exhibition of Antiques to Britain. Three Reasons Listed (学术界反对古物运英展览列举三项理由)”, World Daily News (世界日报), 20 January, 1935. Also see Xu Wangling (徐婉玲), “The International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London in 1935 and its Impact (1935年伦敦中国艺术国际展览会始末及其影响)”, China Reading Weekly (中华读书报), 18 December 2019.

[29] Fu, 2014, 150.

[30] ‘Art Cargo in Warship. Priceless Exhibition from China’, Daily Sketch, July 22. 1935.

[31] The media coverage on the 1935 Exhibition is extremely extensive. In China, Shenbao (申报, aka Shun-Pao) reported the exhibition closely. In Britain, RA hired Alleyne Clarice Zander (referred as Mrs Zander in documents) as publicity agent, then a publicity manager in 1934 to 1946, being charge of the publicity and press-cutting archive of the exhibitions held at the RA. See RAA/PC/1/26. 6 March 1934, 26 June 10 1934, 17 March 1936.

[32] ‘Chinese Art. Complementary to European. A Revelation to Britain’, The Times, December 3, 1935.

[33] After the 1935 Exhibition, the RA did not have exhibition of foreign art until the Exhibition of Art from India and Pakistan in 1947-48.

[34] Cheng, T. F., East and West: Episodes in a Sixty Years’ Journey, (London: Hutchinson, 1951).