Re-Colonizing Memory

Guadeloupe’s Slavery Museum and the Struggle over Identity in the French Caribbean

This building is a statement. When you enter the port of Pointe-à-Pitre, the capital of the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, you do not see an imposing cathedral, a government palace or a stadium. What catches your eye is a museum. A modern structure, covered with a metallic grid evoking tropical trees’ aerial roots, stretching for some 100 meters along the port basin. A museum not on some pleasant theme of entertaining nature, but on the most painful wound in the history of any Caribbean community: slavery.

The “Mémorial ACTe” Museum in Pointe-á-Pitre, Guadeloupe. Photo: Bert Hoffmann

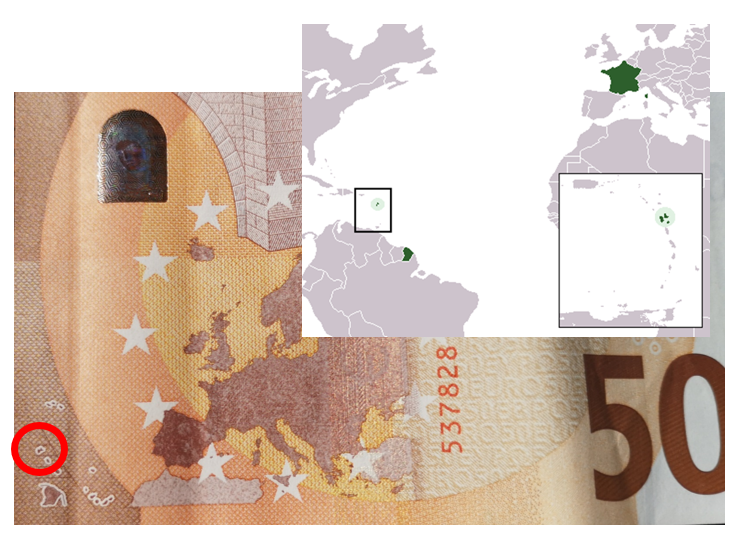

Guadeloupe, that means: France. The Tricolore and the French police in the immigration offices remind you, if needed. A small archipelago in the Caribbean, 6,700 kilometers from Paris, that became French in the colonial era. Today, Guadeloupe is a Département[1] of the French Republic with all its rights and, hence, also part of the European Union. Outside of France, few Europeans are aware that they even have it on their Euro bills: in a little annex to the map of Europe, grouped together with the silhouettes of Martinique, La Réunion and French Guayana.

Guadeloupe, 6,700 kilometers from Paris – but on the Euro bills. (map: Wikimedia, bill: Bert Hoffmann)

In mainland France, the struggles of activists and scholars have put the colonial past on the agenda of memory politics since the 1980s. As a result, the Atlantic port cities made rich by the transatlantic slave trade have seen streets renamed and new museums opened, such as the Musée du Nouveau Monde in the former mansion of a sugar-baron in La Rochelle or the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in Nantes. Following the first-ever mass demonstrations led by Afro-descendants in Paris in 1998, the French National Assembly passed the milestone “Taubira Law” on 21 May, 2001, which recognized the transatlantic African slave trade as a crime against humanity.

In the French overseas communities, these issues play out differently. In a society like Guadeloupe, 90% of the population can trace their descent to enslaved Africans put to work on French plantations. The memory of slavery thus touches on the core of social identity and also on the island’s political status. Since the 1970s, recovering the population’s African roots and memorializing slavery and resistance have become key demands of activists and radical groups, often linked to the cause of eventual independence from France. The prominent museum in Guadeloupe, whose planning began in 2005 and which opened its doors in 2015, is a response to these pressures. It is the French state’s grand attempt to come out of the defensive and, instead, to construct from the very memory of slavery and its abolition a positive narrative of the French Republic. It is aimed at reconciling the island’s population both with its historic past and its present political status.

The ambition of the project is matched by its spectacular architecture, state-of-the-art technology in its exhibition rooms, the building’s exquisite lightning at night and the XXL coffee table book-style catalogue. The team behind the project knew how to link it up to progressive discourse: of course, they don’t call it a “museum”, but a “Mémorial ACTe” (or “MACTe”, for short), to highlight that it is “memory in action” (p. 379).[2]

But under the museum’s shiny surface, the political burden weighs heavy. The quest for a “good” French narrative comes at the price of silences, omissions and a twisting of history which is hard to swallow. For someone who studied the issues of race and inequality in other parts of the Caribbean, the irritation begins right at the start: The permanent exhibition opens with no one else than Columbus. The twist is the Admiral’s veneration of the so-called “Black Madonna”, the Virgin of Guadeloupe in the Spanish monastery of Cáceres, after which he named the island. We thus enter history not via Africa, the place of origin of those who were enslaved and taken to the Caribbean by force, but through the eyes of the Caribbean’s “discoverer” at the service of the Spanish empire.

The MACTe is a project of identity formation. The identity on offer, to be sure, is not “Afro‑” or “Black”. Quite the contrary: the MACTe goes to great lengths to avoid presenting an African legacy for visitors to be proud of. After declaring the Virgin of Guadeloupe to be “the first black woman of the Caribbean” (p. 26), the second black person of the Americas we are introduced to comes similarly unexpected. It is Juan Garrido, a man of West African origin, who in the early 1500s came to accompany the Spanish in their conquest of the Caribbean, Florida and Mexico. A black conquistador. An interesting biography, no doubt, but above all: nothing could be further away from identifying black identity in the Americas with any anti-colonial notion.

The museum proposes to embed slavery in the French colonies in the broader context of slavery throughout the ages and across the globe. In principle, this can be a valid endeavor. But the way the MACTe portrays slavery as “ubiquitous” (p. 88), as something that has always existed, from Ancient Egypt to the Third Reich, it is a framing which serves to relativize the crime of the transatlantic slave trade committed by the European powers. The exhibition does report that 12 to 13 million Africans were enslaved and taken to the Americas between 1501 and 1867; however, this is not referred to as a “crime”, but instead as “one of the biggest tragedies in the history of the human race” (p. 122).

The relieve function of comparison becomes particularly visible when the MACTe reports similar numbers for what it calls Africa’s “traditional or internal slave trade”, citing estimates of 10 million victims for the trans-Saharan slave trade and 5 million for the East African trade (p. 114). The exhibition also underscores the role of African kings who raided other communities to sell the captives to the European slavers. While Afro-descendant activists might at times tend to glorify Africa, the MACTe is doing the opposite with remarkable zeal. Its exhibition also ends on this note: As the last room fast-forwards to the present, the pressing issue of today are not persisting racist legacies or socio-economic hierarchies. Instead, an interactive screen maps the ongoing existence of unfree labor in the world. Choosing this perspective provides an easy way out for Europe. Regarding this category, it fares well. The supposed problem-continent, lit in red, is Africa.

Where slavery persists: The MACTe’s room on the challenge of today. For documentation purposes reproduced from: www.esclavage-memoire.com

Given the thrust of this narrative, it seems no coincidence that the most iconic image of the entire exhibition is not linked to transatlantic slave ships, but to the intra-African slave trade: a series of busts of captive blacks, chained to each other by metal necklaces to be sold at the ports of Africa’s “Slave Coast”. When France’s former president François Hollande came to Guadeloupe for the inauguration of the museum in 2015, his public relations staff chose these busts, highly aestheticized and with bare female breasts in the foreground, for the photo to circulate in the world press.

Official press photo showing French President Hollande at the inauguration of the MACTe. Photo: Présidence de la République (reproduced for documentation purposes)

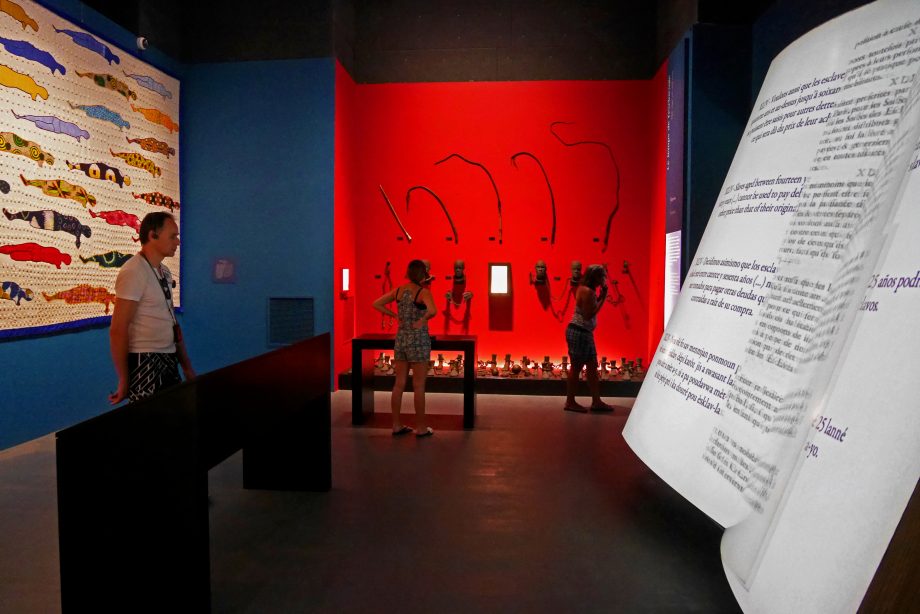

The visitor’s irritation continues in the rooms on the practice of slavery in the plantation economies of the French colonies. Not that the exhibition would deny torture and violence. Indeed, a gallery presents the instruments of repression: bullwhips, chains, shackles, iron masks- a dark arsenal of quotidian terror. The trick is in the framing: The same room displays a super-sized version of the Code Noir. This collection of laws and regulations governing the slave system under French rule is a document of bureaucratic monstrosity. Slaves were property but could not be mortgaged. No slave markets were allowed on Sundays. Fugitive slaves absent for a month should have their ears cut off and be branded. And so on, in 60 articles. The audio-guide then presents an unexpected connection between this and the instruments of repression on display: The plantation owners, we are told, used these in spite of the fact that the Code Noir prohibited torture! The French colonial state is portrayed as establishing rules and caring for the protection of the slaves, but, alas, it was unable to reign in the cruelty of the planters.

Whips, chains, shackles – and an oversized copy of the infamous “Code Noir”. For documentation purposes reproduced from: www.agence-explosition.com

While walking through the exhibition, in spite of the shackles and chains, the system of slavery in the colonial plantation society acquires an awkward sense of normalcy. An ambience of “Such were the times!” is cultivated – for instance when we read that “slave penal law (…) in terms of corporal punishment, was similar to military law applicable to soldiers” (p. 154). Many of the engravings, drawings and paintings on display reinforce this normalization. They are essentially decorative, presented without a contextualization of the source. The idyllic depictions of sugar harvesting on the island of Antigua by William Clark are shown without any mention that the artist was a plantation overseer himself. Even outright visual propaganda, such as the engravings of Haitian rebel slaves massacring French civilians, are reproduced as illustrations with no comment.

This normalization of slavery reaches a climax when the museum resorts to animated movies to show “the daily lives of four slaves.” A farm slave’s work on the field is shown hardly different from field labor today. An old carpenter is shown representing the category of what was then called “talented negro” (“nègre de talent”), explaining to a youngster the merits of learning to be good at a craft. Another of the daily life stories is that of a young female domestic slave who is shown choosing to become the mistress of her owner in order to gain some “upward mobility”. Local critics sharply protested this representation of the enslaved black female being “happy to be her master’s sexual object” (Lettre Ouverte 2016). Moreover, the same animation depicts a “free black” as a thief and rapist, complying with the racist stereotypes. The Guadeloupean Afro-activist magazine “Racines” dedicated an entire issue to what it saw as the MACTe’s shortcomings and blind spots, including suggestions for remedies (Racines 2016). However, five years after its inauguration, the permanent exhibition remains unchanged.[3]

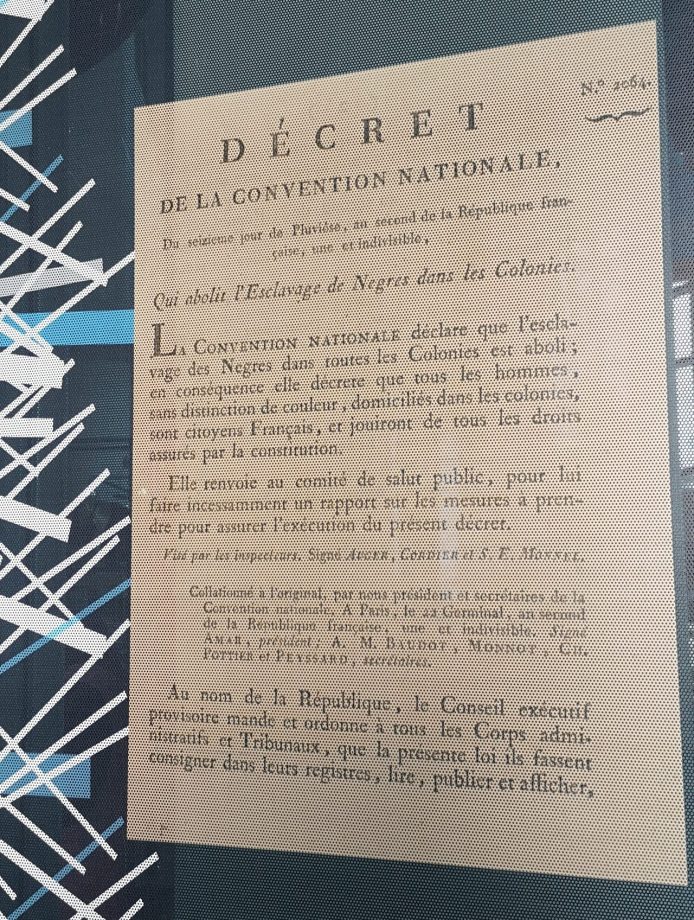

The MACTe seeks to reconcile Guadeloupeans with their past and with their present. To this end it seems functional for the MACTe not to put too much focus on the heroes of resistance, such as the maroon communities of run-away slaves or the leaders of the Haitian revolution who in the wake of 1789 through off the colonial yoke to proclaim the first independent black republic. Even the prominent black voices among the abolitionists are absent from the exhibition. Instead, the museum’s narrative has a different protagonist: La République. The grand moment of pride in the course of the exhibition has come when, in the wake of the French Revolution of 1789, “France [is] the first country to abolish slavery” (p. 264). This, the French National Assembly’s decree to end slavery, is the pivotal piece of the MACTe’s exhibition. It is also featured as a poster at the entrance. The French Republic is the hero of the story the museum tells.

The poster at the museum entrance: The French Republic declares the abolition of slavery. Photo: Bert Hoffmann

The abolition of slavery, however, was short-lived. Only a few years later, Napoleon reinstated slavery in the colonies. The museum dedicates a whole room, lit in brightest red, to portray Napoleon with his infamous dictum, according to which “freedom is a food for which the stomach of Negroes is not prepared” (the translation is that of the official MACTe catalogue, p. 277). The room’s visual effect is strong, no doubt. But it makes the return of slavery an issue of personal failure. It is suggested that Napoleon’s racial prejudices went against the humanist ideals of the revolution. No word is lost on the fact that the abolition of slavery undermined the economic foundation of the French Republic, and that it was not only Napoleon who wanted to keep the profits and privileges that were derived from it.

Napoléon Bonaparte, who reinstated slavery in the French colonies, on display in the MACTe. For documentation purposes reproduced from: www.agence-explosition.com

Eventually, in 1848, the French Republic abolished slavery for the second time. In the MACTe’s narrative, this date becomes the moment of birth of what is Guadeloupe’s society today. It also provides the baseline for a very practical project of genealogic research that is linked to the museum. After 1848, more than 80,000 “newly free” blacks were registered and given new family names. The French République is thus portrayed as the midwife of liberty and identity. Today, these names persist as the family names of most Guadeloupeans, and the “Our names” project (Non an Nou, in Creole[4]) calls on the people to look up the origin and pedigree of their name. Searching for the “roots” here no longer refers to some distant African past, but to the concrete ancestors at the moment of becoming “free and French”.

The French overseas possessions in the Caribbean are unique cases of de-colonization. They did not become sovereign states, but as early as 1946, Guadeloupe, Martinique and Guayana became full-fledged administrative units of the French Republic, with rights and representation just as the departments of mainland France. This is in marked contrast to, say, the situation of Puerto Rico, which remains associated to the United States in a quasi-colonial status, without representation in Congress.

While there always have been political groups striving for independence, integration into the French state has – from all we can tell – broad backing in Guadeloupe (albeit coupled with strong sympathies for more autonomy). Not only would many not want to give up the privileges of EU passports and French social welfare programs, but with the high out-migration to the French mainland and the social networks resulting from it, Guadeloupean society has become trans-Atlantic in new and important ways. It seems legitimate that in this context the political quest may be less about sovereignty, but rather to seek – despite the colonial past and geographic distance – inclusion without discrimination within the French state.

But this would not need to include “re-colonializing memory” in the form of the MACTe’s narrative on slavery. A multi-cultural nation – as France certainly has become – can and should accommodate for a variety of social and cultural identities with each cultivating pride in their own histories, traditions and protagonists – even where these stand at odds with the dominant script of the country’s colonial past. Moreover, all of French historiography stands to benefit from such a process of critical review.

The MemorialACTe museum in Guadeloupe is, despite all its shortcomings, an important step forward in that it draws the legacy of French colonial slavery into the spotlight of public debate. If the MACTe is to be – as its name proclaims – “memory in action”, it should not close, but open that debate.

Bert Hoffmann is Lead Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) and professor at the Freie Universität Berlin. His recent publications include When Racial Inequalities Return: Assessing the Restratification of Cuban Society 60 Years After Revolution (together with Katrin Hansing); in: Latin American Politics and Society vol. 62, no. 2 (summer 2020), p. 29-52. (Open Access).

Footnotes

[1] To be precise, the archipelago that makes up Guadeloupe is at the same time a “département” and a “région”, making it a “région monodépartementale”. It is a full part of the European Union, but outside the Schengen Area.

[2] The MACTe prohibits to take photos in the museum; cell-phones have to be deposited at the entrance. Therefore, all citations with simple page numbers are from the museum’s catalogue in its English version as listed in the references (MACTe 2015). Where the museum’s descriptive tables and audio-guide are referred to, this is to the best of the author’s memory, but without the exactness of the references to the catalogue.

[3] Paraphrasing the Taubira Law’s designation of slavery as a crime against humanity, the Racines magazine decried the museum as a “crime against memory” (Racines 2018). These quotes are just glimpses into the debate on the MACTe within Guadeloupe, without any claims to be representative. Moreover it is beyond the purview of this blog post to engage with the broader French and international scholarly debate on memory politics regarding the past of colonialism and slavery.

[4] For the website of the project see http://www.anchoukaj.org/nomination_guadeloupeens.php

References:

MACTe catalogue (no date): Memorial ACTe. Exploring Slavery & the African Slave Trade in the Caribbean and Around the World [Catalogue of the Exhibition, edited by Thierry L’Étang]; Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe: MémorialACTe Publisher

Lettre Ouverte (2016): Lettre ouverte à Monsieur Le Président du Conseil Régional (Le Mémorial ACTe en questions); documented at: http://www.madinin-art.net/le-memorial-acte-en-questions/ (8 Nov 2016)

Racines (2016): Mémorial ACTe. Descriptions, Analyses, Critiques, Commentaires et Suggestions; Racines. Trimestral Guadeloupéen Conscience et Culture Nègre; No 39, May 2016

Racines (2018): Le MACTe. Un crime contre la mémoire; p. 15-16; Racines. Trimestral Guadeloupéen Conscience et Culture Nègre; No 43, June 2018