Paris, a Deserted – Quiet City?

Impressions from France

The Covid-19 epidemic has changed everyday life in Paris dramatically. More so, during the last month since the government announced that France entered the 3rd phase of the epidemic (defined as “sporadic cases or small clusters of disease in humans. Human-to-human transmission, if any, is insufficient to cause community-level outbreaks”) (Pandemics WebMD Medical Reference 2020: 1) on 14 March 2020. Supermarkets, pharmacies, banks, press outlets and essential public services remain closed until further notice and all citizens are required to fill in ‘a statement of responsibility’ stating the reason why they need to leave the house. How do citizens react to this unexpected and unusual ‘violation’ of their everyday life which they consider as an ordinary reality?

Image 1: Place de l’Institut, Quai de Conti, 6th arrondissement, this photo is personally taken on 01 April 2020.

Indeed, preparing for an epidemic had surely never crossed anyone’s mind, yet the implementation of national plans – urging people to stay at home and imposing travel bans – suddenly turned the tables on the population, both psychologically and socially. All of a sudden, this epidemical surveillance came to affect nations on a global scale, generating a sense of helplessness and fear. This reaction affects all people, everyone dealing with this emotional impact differently. Some coping better than others depending on their psychological and emotional vulnerability. What will be the impact on social solidarity in a period of general crisis? How can we tackle solitarity? Apparently, in times of hardship, human beings are known to transcend hardship, privation, and tribulation, yet a conflict between individual happiness and moral obligation seems to emerge. Albert Camus’ “The plague” (1991), an illustration of this metaphysical issue, depicts how both individuals and community expose their vulnerability where, in times of crisis, all facets of extraordinary social behavior become apparent whether it be discrimination, antagonism or self-interest.

As a Greek student in Paris, I have the advantage of witnessing with my own eyes what is happening here, since I have chosen to continue my MA studies in Anthropology-Ethnology. I have thus noticed that in recent days there have been intense discussions in social media about people belonging to vulnerable groups (homeless, migrants, refugees, people in nursing houses, etc.) and the protection policy that will follow as well as more general references to social solidarity. As I was about to walk out of my apartment, I was struggling with the idea of what I would encounter beyond the door. While I was hoping to find things unchanged, I looked around: things have changed… I witnessed it in the eyes of passers-by that I used to greet. I had this eerie feeling I was about to embark into a ‘new reality’ of people enacting the social distancing policy. What, then, are we to expect from now on? Will this world see humanity change its stance? How will this whole ordeal shape the empirical sciences? Will it define a new community? Reflecting upon what I have been taught so far in my fruitful years at the university, here is my anthropological perspective of what I witness in my quarter…

First reactions

‘Solitarity’ versus ‘solidarity’

At first, people continued to live their normal lives ignoring instructions to gather outdoors in public spaces in quarters like Saint-André-des-Arts or Saint-Germain-des-Prés as well as indoors in restaurants, bars, using public transportation without required protection. I asked some of them why they were not protecting themselves. “We will continue our lives as usual,” they responded. “After all, it is Saturday, we want to hang out with our friends. No one wants to be alone on a Saturday night.”

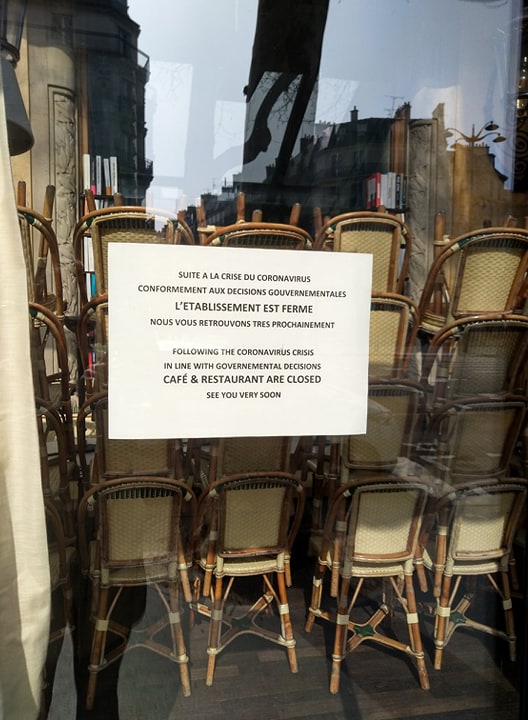

Image 2: An announcement at a well-known café of Latin Quarter: “Following the coronavirus crisis in line with governmental decisions café & restaurants are closed. See you very soon” It was taken by me on 01 April 2020

But is this solitarity a real issue becoming obvious or is it fictitious? This question arises from various dimensions of social experiences shaped by religious expectations, educational and cultural inheritances affecting our larger social interactions. In hardship and oppression, one factor that seems related to individual differences in reactions under such circumstances, is repression of any prosocial behavior. This is part of an individual’s defense mechanism, as a factor of psychological well-being when coping with challenging life situations as opposed to the usual norms of collaborative empathetic behavior crucial to social cohesion. Solitarity is linked to the biological survival of the individual in a profound crisis. According to the Hobbesian political theory in the absence of any social contract, everyone has the right to everything where individuals tend to revert to a state of nature linked to fear. As such, a person must do what he/she believes best preserves his/her life. This elicits a need for adaptation to a new reality and converts to social distancing where the individual solely evolves around his own self-interest. Could Covid-19 actually encourage social distancing and other forms of deviance when all this blows over? A compelling argument would be to say, “collective efficacy” (Inderbitzin & Bates & Gainey 2017) that is, “the ability to recognize common goals of a safe environment, would be a necessary condition for social cohesion”. It could go either way… it remains to be seen…

In modern societies, increasing loneliness has become an especially important social phenomenon. While interactions between individuals are constant, many people feel a painful feeling of isolation. Many feel lonely while they are with other people “under the same roof” (Ben-Ze’ev 2014). “The most prominent feeling in life was the feeling of loneliness, even when, or especially when, I was with another person” (Ben-Ze’ ev & Goussinsky 2008). Loneliness under such conditions “is an emotional hindrance because it has been imposed and despite someone having created intimate even sharing the same environment” and feeling a sense of belonging, “certain relationships bring loneliness” (Cacioppo & Patrick 2008). Loneliness has nothing to do with “being alone”. Being alone is by choice, a desired solitude. Loneliness, on the other hand, is fatiguing, it is debilitating and leads to maladies, such as depression and even suicidal tendencies. The kind of loneliness, people seem to be experiencing now is the “no time for me”, where everyone is busy with their own issues, their own well-being and consequently, relationships enter into a new phase. Thus, the social scene changes absorbed by the ‘every man for himself’ involving individualism in periods of panic or emergencies (Rokach & Sharma 1996: 827). In order to achieve the desired aim, empathy is essentially what keeps together a somewhat civilized society. Yet, what lies behind this altruistic theory, is how to reinforce such practices to a whole community. Is it a matter of simple communication or something deeper?

“Social solitude” in contrast to “solidarity,” according to the philosopher Martin Buber, “is the self-estranged person who has no contact, neither with himself nor with other people” (Friedman 1986: 97). Solitarity is a painful relational experience, in which the person’s contact with oneself and the environment is absent. The person feels alone, isolated, detached from him- or herself and others. Loneliness is often silent and accompanied by helplessness, lack of hope for building relationships, futility, shame or even a deep sense of personal nonexistence. So, I wonder, if, perhaps, several population groups, who were already marginalized or socially stigmatized either by their physical disability or homeless status, have now been completely socially isolated by governmental law… These people are “on the sidelines”, but now that there is a need for mandatory isolation precautions, because of the epidemic, how would people react? How can people who are already accustomed to a solitary living because of social marginalization, be isolated because of a virus situation?

Marginalization delineates social groups living in peripheral and adverse situations. However, in the changing context the process of marginalization has acquired several new dimensions besides the redefining of old ones in the emerging contexts. The long review by Martine Xiberras (1993) of the sociological literature defines that exclusion is a result of a general breakdown of social and symbolic bonds, such as economic bonds. This sentiment of an existential threat is what leads to strife as well as marginalization where “the ethos of responsibility which calls for social connectedness,” (Sofroniou 2020) is eradicated.

According to Émile Durkheim, on the other hand, social facts, such as solidarity, are very important and ought to be studied seriously. Durkheim describes social solidarity “as the belief systems and institutions which play a vital part in giving societies “coherence and meaning” in the way we relate to each other” (Durkheim 1897: 208-209). He was also fascinated at how society was changing and transforming by creating new social situations “social conditions.” Durkheim illustrated how things that were important to a society and glued everything together such as values, morals and customs were changing over time and to him this played a part in his conclusions on the rates of people who could not adapt to the changed conditions (Giddens 1997: 77). He distinguished two types of society: the most primitive was characterized by “mechanical solidarity,” while the most modern by “organic solidarity” (Coser 1971:30). Durkheim’s broader theoretical assumptions concerns evaluate how functional integration is organized by an organic solidarity- solidifying social bonds, yet in today’s marker driven society emphasizing individualism, this traditional pattern of social embeddedness changes. Collective consciousness shifts because our conditions of existence have changed. Instinct always has more compelling force than reason “because it becomes more rational, the collective conscience becomes less imperative and for this reason, it wields less restraint over the free development of individual varieties” (Durkheim 1893: 149). This feeling – allegorically – is not unique to today’s epidemic crisis, as enforced solitude is opposed to voluntary solitude which creates an unpleasant distance within the context of one’s relationship, maybe because we are unwilling to share our vulnerability. Thus, we start drifting in different directions. Just then, when you become self-aware of the situation, you endure the lockdown on your own (Bergmann & Hippler 2017).

In trying to explain how social ties influence health and social behavior, Mary Bassett, MD, MPH, director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB), Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University, claims that epidemics are both biological and social (Bassett 2020). Therefore, epidemics reveal fissures within society. As a casual observer myself, I am left with the impression that people are disconnected by harboring modern man intellectual hubris, in which, contrary to Durkheim’s ideal type of society, cohesion is largely the result of resemblances. Even so the challenges and difficulties that may inhere in relationships, may deepen in that, the virus becomes deadlier as it creates “a self-reinforcing cycle that could have consequences for years to come” (The New York Times Fisher & Bubola March 16, 2020).

Image 3: Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville (City Hall) in Paris, France, is the building housing the city’s local administration in the 4th arrondissement. It was taken by me on 20 April 2020

As the crisis deepens

With the pandemic proceeding, I noticed a general change in the behavior of people. They have become more irritable. One day, in the subway, for example, a man approached a woman closer than the arbitrary distance according to public restrictions and guidelines for protection and she immediately punched him, shouting and cursing. He fought back by hitting her. So how does an epidemic change people’s need for communication, dialogue, and exchange of views? Suddenly there is a veil of distance, an obstacle between people bestowing isolation, anonymity, the idiom of seclusion. Any breach of this distance – veil, is a breach of personal space and automatically leads to violent reactions in some cases.

It is well known that an outbreak of violent behavior is no uncommon phenomenon in times of socio-economic crises. “During the epidemic, (…) our conflicts just grew bigger and bigger and more and more frequent, everything was exposed” (The New York Times Taub April 6, 2020). Thus, at a later point, as I was going to the supermarket on the boulevard of Saint Michel, I was struck by a man shouting and beating up another man, a homeless person. When I asked what happened, he replied that the homeless man had been following him from his house to the supermarket until he finished his shopping. He then jumped on him trying to steal the shopping bags full of food. None of those present at the supermarket reacted at all. Are we witnessing here an example of the failure of social solidarity? I wondered. How is solidarity defined or redefined given the present crisis?

The question ran through my mind over and over again, as I walked back home, another incident revealed emerging forms of violence in everyday life. Opening the door of the old five-story apartment-building where I live, I faced a homeless man who had sneaked in with all his belongings. As days went by, the words of another homeless man echoed in my ears when I asked him why he does not ask for help from the state: “I don’t want anything from the government. They let me down. It is because of them that I am on the street. All I want is kind help from my fellow human beings. I’d rather die than ask for governmental aid because it’s a sure death”.

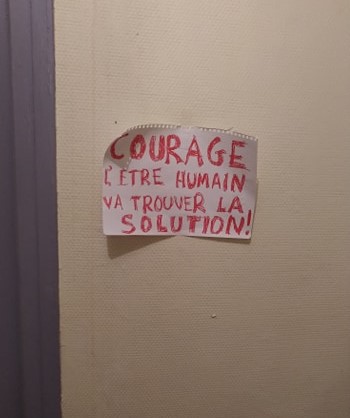

Image 4 In the building where I live, this personal message is on the wall: “Courage, mankind will find the solution.” It was taken by me on 01 April 2020

At a time of crisis, such as the current global health crisis, I wonder what is the general impact on the inhabitants of cities? Most are inside their houses due to the government’s restraints. In Paris, the apartments are about 20-30 sqm and in the area of the Latin Quarter they are even smaller. How long will people be able to stay inside? How long will they be optimistic without being able to interact with other people? Can those who do not have a kitchen or a bathroom in their house cover the needs of food and subsistence? What happens with those who must share common areas? In Paris, because housing is scarce, it is not uncommon to find communal areas and shared facilities, which often may lack basic kitchen facilities, and many have to even share a bathroom.

A positive power-giving event

A joyous event and perhaps a new habit that everyone expects in the day is the symbolic applause at 8 p.m. All the residents come out to the windows clapping, making noises and cheering “bravo,” as a unifying symbol. “Well done” showing appreciation to those who work amidst the difficult conditions, “well done” to doctors and other medical staff who save lives, but also an important “well done” to themselves and their neighbors who have managed to stay healthy. This is something that proves that there is still hope. It is the applause that acknowledges life against death. I noticed this, as a few days ago when I hesitated to open the window to join in on the applause myself. But when I finally decided to go to the window, I saw the neighbor across the street smiling, looking at me, with great relief, shouting “well done girl.” At that moment, no matter how bad you feel, no matter how lonely you get, your attitude, your frame of mind and spirit changes and you gain strength. This is the moment of dialogue and interaction with other . “You can live alone without being lonely, and you can be lonely without living alone, but the two are closely tied together, which makes lookdowns, sheltering in place, that much harder to bear” (Lepore 2020).

Written on 30 April

Artemis Skrepeti is currently a graduate student in M.A. studies Anthropology-Ethnology in the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences at the University of Descartes (Sorbonne, Paris 5). She specializes in Kinship Anthropology.

Contact: artskrepeti@yahoo.com

References

Bassett, Mary, T. 2020. Association of American Medical College. In The new coronavirus affects us all. But some groups may suffer more. by Weiner, Stacy. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/new-coronavirus-affects-us-all-some-groups-may-suffer-more Last access: 27/04/2020.

Ben-Ze’ev, Aaron. 2014. Loneliness. Living Apart Together. What is so painful in romantic loneliness?https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/in-the-name-love/201408/living-apart-together. Last access: 30/04/2020.

Ben-Ze’ev, Aaron & Goussinsky, R. 2008. In the name of love: Romantic Ideology and its victims. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bergmann, Ina & Hippler Stefan. 2017. Cultures of Solitude. Loneliness, Limitation, Liberation. Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH. Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften.

Cacioppo, John T. & William Patrick. 2008. Loneliness: human nature and the need for social connection. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Camus, Albert, 1913-1960. 1991. The plague. New York :Vintage Books

Coser, Lewis. A. 1971. Masters of Sociological Thought: Ideas of Historical and Social Context. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Durkheim, Emile. 1893, 1978. De la division du travail social. Paris : Presses Universitaires de France.

Durkheim, Emile. 1897. Suicide, a study in sociology. J. A. Spaulding, & G. Simpson, London: Routledge.

Fisher, Max & Bubola, Emma. March 16, 2020. As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens Its Spread. In New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/coronavirus-inequality.html Last access: 27/04/2020.

Friedman, Maurice. 1986. Martin Buber and the eternal. New York: Human Sciences Press.

Giddens. Anthony. 1978, 1997. Durkheim. Fontana Press. Modern Masters.

Inderbitzin, Michelle L. & Bates, Kristin A. & Gainey, Randy R. 2017. Deviance and Social Control: A Sociological Perspective 2nd Edition. Sage Publications, Inc

Lepore, Jill. 2020. The History of Loneliness. Until a century or so ago, almost no one lived alone; now many endure shutdowns and lockdowns on their own. How did modern life get so lonely? https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/the-history-of-loneliness/amp?fbclid=IwAR2GFolnYOPZbnU-KeGc2Z12JXP21OyweUQQ8IOHTLo6cyrhKcER_YkvX-E Last access: 24/04/2020.

Lloyd, Sharon A. & Sreedhar, Susanne (eds.). Spring 2019. Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Pandemics WebMD Medical Reference. 2020. What are the phases of pandemics and what do they mean? https://www.webmd.com/cold-and-flu/qa/what-are-the-phases-of-pandemics-and-what-do-they-mean?fbclid=IwAR1vJOs0woYDnYKHkB7AXRAqBnsUMTxlVJG7w3Xod9-yGH_ny0q5N0JpUtg Last access: 20/04/2020.

Rokach, Ami & Sharma, Monika. 1996. The Loneliness Experience in a Cultural Context. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, Vol. 11. Issue 4.

Sofroniou, Andreas. 2020. Ethos, Individual, Social, Cultural, Institutional. Lulu.com

Taub, Amanda. April 6, 2020. A New Covid-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide. In New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html. Last access: 30/04/2020.

Xiberras, Martine. 1993. Les theories de l’Exclusion. Paris. Meridiens. Klincksieck.