Pandemic Affects, Planetary Specters, and the Precarious Everyday

Encountering Covid-19 as a Nomad with (Half)Grown Roots

“Ein Gespenst geht um in Europa.” A specter is haunting Europe. – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848)

![]() Until there is breath, there is hope! A Bengali Proverb[1]

Until there is breath, there is hope! A Bengali Proverb[1]

“Material nature, it is said, is the reason for cause and effect and agency; the person is said to be the cause in the experiencing of happiness and unhappiness”. – Bhagavad Gita (8th/9th-century B.C.E.)[2]

Pandemics are planetary specters that haunt our more-than-human world. The “specter” of planetary destruction in the Anthropocene remains “the event of our time” (Ruddick 2015, 1115). Calling the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) another planetary specter heightens the serious material nature of the pandemic, the extremely rapid loss of vulnerable human lives, the fragile health systems, and personal/professional livelihoods cracking under pressure worldwide. The spectral and spectacular material nature of the latest pandemic of the twenty-first century also brought forth a parallel rise of existential Angst with a range of pandemic affects.

Anthropologists, among others, are caught in the occupational dilemma of suspended travels elsewhere. Given the precarity of working conditions and the affective labor[3]

of perpetual productivity that early and mid-career anthropologists in Germany are expected to perform (irrespective of the living and emotional costs of a real-time pandemic), how can we possibly write about the Covid-19 dispassionately? Encountering Covid-19 is more than witnessing and articulating the pandemic for others. It is about expanding the horizons of thinking, feeling, and imagining as affective scholars (Stodulka, Selim, and Mattes 2018). This blog piece draws from some of my pandemic encounters in 2020-2021 across Kolkata and Berlin and an effort to step out of the silencing effects of precarity, mourning, and forced isolation.

Fieldwork interrupted…

“It is not a good time to visit India. #CAAProtests #DelhiRiots. It is not a great time to travel anywhere. #Covid-19” (Fieldnote 28 February 2020). I jotted down these two lines in my diary, pondering whether to tweet or not to tweet, as I waited for my flight at Berlin’s Tegel airport. I saw only the security check personnel wearing surgical masks and disposable gloves, with very few fellow passengers (among hundreds) wearing filtered masks, seeking social distance in an overcrowded waiting room. In February 2020, Covid-19 in Germany was still considered a local outbreak running wild, having crossed the China borders to reach three countries so far: South Korea, Iran, and Italy. I paid little attention to the epidemic at that time, worrying more about the uncertain future of an ethnographic venture in Hindutva afflicted India.

Pre-Covid-19 Kolkata. The flower seller at the street corner of Beckbagan Row covered her face to protect against air pollution and not the virus. 15 March 2020 © Author

Two weeks later, I intentionally stopped following the news about the Covid-19 outbreak. I focused on my exploratory fieldwork in Kolkata with a naïve desire to escape the obsessive public talk about the Corona-moyee (afflicted with Corona) Kolkata[4], although the virus had not officially reached the city yet. Sipping ça (black tea) and sitting under the shade of a verdant Tamarind tree in a South Kolkata neighborhood, I was ambivalent about the local and global preoccupations with what might turn out to be a brief episode. By noontime on 11 March 2020, the outbreak was on its way to make headlines across the front pages of the local newspapers (the Anandabazar Patrika and the Daily Telegraph): The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 as a pandemic. In the next few days, my life plans, like millions of fellow humans, went through a sudden, synchronic change. The government of India was about to shut down all flights to and from India from 22 March. I barely managed to secure an early morning flight on 19 March and returned to Germany. My fieldwork was interrupted by Covid-19, and until today, setting a date for Kolkata remains unpredictable.

Near and far encounters

“Do not sneeze! Do not even think of coughing in front of the immigration desk!” Watching me sniff and blow my nose, my friend and interlocutor D. warned me, anxious that I might land up quarantined for 14 days in India. I had arrived in Kolkata with chronic sinusitis, and the condition did not get any better. The ayurvedic physician that I had sought for a nasya[5] treatment kept calling me during the last few days of my stay, asking if there was any sign of fever or breathing difficulty (Telephone conversations with Dr. K., 16-18 March 2020). As India declared the initial number of diagnosed Covid-19 cases, the anxiety of the ayurvedic physician had grown exponentially, and mine too. Standing at the airport check-in desk during midnight hours, I barely saw the expression on the masked face of the immigration office. A wave of acute anxiety took over me: Should I now get tested or not? I have no fever! But Covid-19 could be asymptomatic! It has been two months since my ENT physician diagnosed rhinosinusitis, allergic, maybe chronic! The airport authority in Kolkata did not check my temperature. And my friends joked about it later, “They were happy that one more foreigner left India!” (Telephone conversation with D., 19 March 2020).

The flight was empty from Kolkata to Doha, and I slept across three empty seats. Qatar had already banned travelers from leaving the Hamad International Airport. The trip from Doha to Berlin was packed with masked men and women. I dozed off behind a FFP2 mask. I had brought five of them from Berlin to deal with the urban air pollution and breathing troubles in Kolkata, a topic I hoped to explore. I used up two masks and left two with D. The remaining mask was now returning with me. During the flight from Doha, my sleepy elbow repeatedly touched the elbow of my fellow passenger, ending up irritating him and making myself angry. The return to Tegel airport was less than spectacular. There were frequent announcements via loudspeakers: “Abstand halten! Keep distance!” The passengers laughed at these announcements. What was the point of instructing everyone to stand two meters apart and maintain social distancing in an overcrowded baggage collection room, where hundreds of passengers were jostling side by side? I stood with my worried face behind the mask, trying not to sneeze and cough, and after an hour left with a taxi, without any examination. “Ich habe schon meine Einkäufe gemacht! I have done my shopping already!” said the taxi driver. He was not wearing a mask and stored inside the taxi several little bottles of Cologne perfume instead of disinfectants. The kind man shared his tips about how to prepare for the gloomy days ahead. Berlin looked deserted and lifeless, unlike the place I had left three weeks ago.

Procession of death and multiple waves: The affective labor of living a real-time pandemic

“There is a procession of death in Kolkata! Mrittyur Micchhil!” My friend D. told me during one of our telephone conversations in autumn 2020. Her mother caught the virus, and we were worried about her. She survived and still suffers from the longer-term effects of the virus with breathing difficulties and coughing bouts. I lost several elderly relatives in Bangladesh who had been suffering from multiple health conditions. My youngest aunt, only a year older than I, was diagnosed with Covid-19 and died in Dhaka. In autumn 2019, she had visited me, and we had planned another, more extended trip together. The procession of death continues, and I stop here before I overwhelm the readers.

Everyone is more or less affected by the socio-material effects of the virus. Yet, not everyone is affected in the same way. There is hardly enough space or support for the affective upheavals that nomads like me go through. Teaching must be continued at all costs, and students must be supervised. Research grants must be written, and publications must be brought out to secure the precarious everyday as a Mittelbau (early/mid-career) anthropologist in a German university[6] . As I uprooted myself from the city of my birth (Dhaka) and spent more than half a decade researching in a German city (Selim 2019), the longing to grow academic roots in the Bengali-speaking Kolkata grew inside me. The pandemic postponed all ethnographic aspirations while the half-grown social and institutional roots in Berlin required consistent care. The persistent affective labor spent living a real-time pandemic across several time-zones multiplied as I began to teach and learn about it.

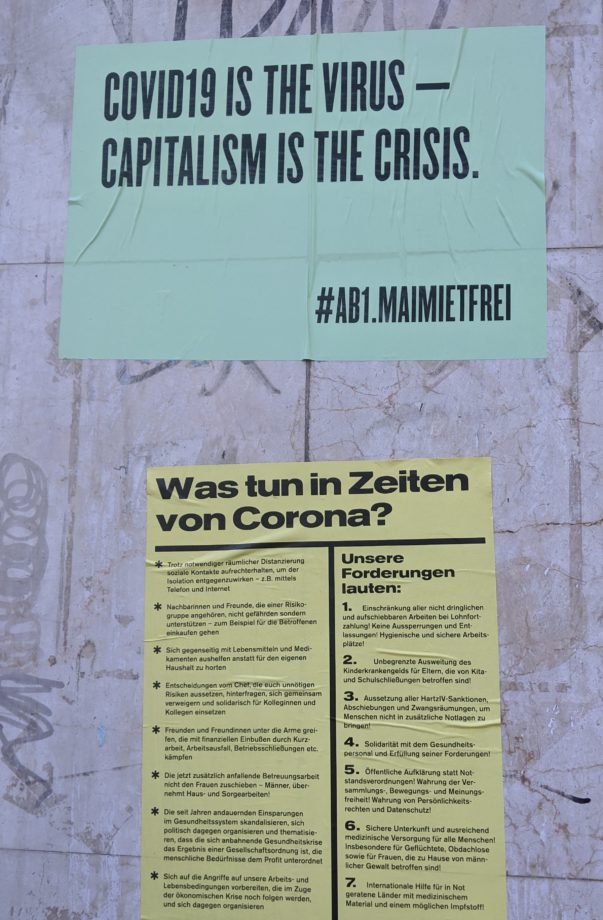

“Covid-19 is the virus – Capitalism is the crisis.” Poster on Maybachufer, Berlin. 21 April 2020 © Author

Since March 2020, Berlin went through the first and second “wave” of Covid-19. Since my return from Kolkata, I isolated myself at home, except for the somewhat brief and over-the-top optimistic summer. I modified the upcoming summer (and autumn) courses into online seminars, tweeted furiously, doing my part in overwhelming fellow netizens with Covid-19 related information. I still felt (and feel) spooked, having encountered a specter haunting the world, in the airports, and flights over thousands of kilometers between two continents. Having returned home, bearing the privilege and the burden of (additional) work, I observe how the specter now stands in quiet discomfort out there, behind the window, while I avoid physical contact with fellow human beings at all costs. I am yet to arrive at the new normal set by a pandemic lifestyle and the trail of blatant inequalities in its reception, diagnosis, and treatment; in its medial, political, and affective performances.

The point of no return to the normal

How does one think and feel the precarious everyday of overwhelming pandemic anxiety? Ethnographers have traditionally been late in catching up with the empirical reality. And Covid-19 will surely turn around our conventional epistemic stance of witnessing, widening our observing-articulating function to focus more on encountering the pandemic. Entangling the existential Angst that we share with fellow humans, what anthropology is today will become history tomorrow. The specter of Covid-19 compels us (once again) to dissolve further the untenable borders of personal experiencing and the theoretical distance of ethnographic reflection.

“All paths are circular,” wrote Ibn ‘Arabi, a 12th/13th -century Sufi philosopher and poet, who survived the plague that ravaged medieval Europe, crisscrossing the waters between North Africa and Southern Europe (Addas 1993, 10). The Sufi master took refuge in a transhistorical engagement with temporality to allay his all-too-human anxiety. As ethnographers, we are creatures hopelessly bound to the politics of the contemporary. Yet, our thoughts must be able to connect the present with the historical and the transhistorical. Widening our academic repertoire, we should perhaps include a material (and metaphysical) imagination as part of our affective repertoire. Because catastrophes such as pandemics stand within and outside of time, reminding us of the fragility of mortal, temporary human existence. Confronted with the planetary troubles makes me think of the pandemic anxiety as a form of existential Angst, a shared predicament of humans, that reiterates within and beyond the persistent cycles of old and new inequalities, and differentiated bio-social vulnerabilities.

The material nature of the unseen (virus) has become the contemporary reason for cause and the effect and agency, running our more-than-human world (Selim 2020). Encountering Covid-19 is more than witnessing the pandemic. It is about transgressing temporalities and taking an active role as affective scholars of the pandemic reality confronting us while traveling and physical immersion with other humans elsewhere, remain temporarily suspended. Divided as we are across class, gender, residency status, and the geopolitics of location (to name only a few dimensions), our fractured humanity is caught up in the experiencing of happiness and unhappiness of our oxymoronic shared yet isolated predicament in corona times. A specter is surely haunting our world. Yet: Hoffnung stirbt zuletzt! Hope, indeed, dies last.

Snow sculptures on Mariannenplatz. The creative imagination of Covid-19 affected Berliners embodies hope. 30 January 2021 © Author

Written on 2 February 2021. Revised version submitted on 6 February 2021.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my friend and interlocutor D. for hosting me in Kolkata and her comments on an early draft of this blog piece. Thanks to my colleagues in the editorial team of #WitnessingCorona Blog series, Hansjörg Dilger and Clemens Greiner, for their feedback on the final draft.

About the author

Dr. Nasima Selim is a postdoctoral research associate with teaching duties at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology of Freie Universität Berlin and co-spokesperson of the working group Public Anthropology of the German Anthropological Association (DGSKA/GAA). She has previously worked as a medical doctor and public health researcher/educator in Bangladesh. Her current research and teaching interests intersect critical global health, post-secular practice, affective ecology, and postcolonial theories. E-mail: nasimaselim@zedat.fu-berlin.de; Twitter handle @NasimaSelim.

#Witnessing Corona

This article was simultaneously published on the Blog Medical Anthropology / Medizinethnologie. Witnessing Corona is a joint blog series by the Blog Medical Anthropology / Medizinethnologie, Curare: Journal of Medical Anthropology, the Global South Studies Center Cologne, and boasblogs.

References

Addas, Claude. 1993. Quest for the Red Sulphur: The Life of Ibn ʻArabī. Trans. Peter Kingsley.

Cambridge: The Islamic Texts Society.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2004. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire.

New York: Penguin.

Johnson, W.J. 1994. The Bhagavad Gita. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jongmanns, Georg. 2011. Evaluation des Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetzes (WissZeitVG).

Gesetzesevaluation im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung. Hannover: HIS: Forum Hochschule.

https://his-he.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Publikationen/Forum_Hochschulentwicklung/fh-201104.pdf.

Loher, David, and Sabine Strasser. 2019. “Politics of Precarity: Neoliberal Academia under

Austerity Measures and Authoritarian Threat.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie sociale 27: 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12697

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 1848. Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei.

https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/marx-engels/1848/manifest/0-einleit.htm

Ruddick, Sue. 2015. “Situating the Anthropocene: Planetary Urbanization and the Anthropological

Machine.” Urban Geography 36(8): 1113-1130. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2015.1071993.

Selim, Nasima. 2020. “Letter from the (Un)Seen Virus: (Post)Humanist Perspective in Corona

Times.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie sociale 28 (2): 353-355.______. 2019. Learning the Ways of the Heart in Berlin: Sufism, Anthropology, and the

Post-Secular Condition. Ph.D. Dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin.

Stodulka, Thomas, Selim, Nasima, and Dominik Mattes. 2018. “Affective Scholarship: Doing

Anthropology with Epistemic Affects.” Ethos 46 (4): 519-536.

Ullrich, Peter. 2020. Mit dem Zukunftsvertrag in die Vergangenheit. Wird die Chance auf einen

Ausstieg aus der strukturellen Prekarisierung akademischer Wissensarbeit verpasst? KWI-Blog, 24 June. https://blog.kulturwissenschaften.de/mit-dem-zukunftsvertrag-in-die-vergangenheit/.

Footnotes

- [1]The proverb re-appeared in a recent article published in the widely circulated Bangladeshi newspaper series, “Life-Stories in Corona Times”: https://www.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/যতক্ষণ-শ্বাস-ততক্ষণ-আশ).

- [2]The Bhagavad Gita consists of seven hundred verses nested within the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata (Johnson 1994, 58).

- [3] Affective labor is the (im/material) labor that “produces or manipulates affects” (Hardt and Negri 2004, 108). In neoliberal institutions, “[a] worker with a good attitude and social skills is another way of saying a worker is adept at affective labor” (ibid.).

- [4] Corona-moyee Kolkata trope circulated widely. A mocking YouTube video appeared on the day I left Kolkata: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxM8cUuPbpc

- [5] Oil based nasal instillation that belongs to the multipronged Ayurvedic treatment known as Panchakarma (five modalities)

- [6]Precarity is not an exception but rather a norm in neoliberal European academia (Loher and Strasser 2019). In the wake of Covid-19, care obligations, residency and employment status (among others) aggravated the existing inequalities engendered by the fixed-contract employment situation of the vast majority of scholars in German higher education and research (Ullrich 2020). The controversial German “Act on Fixed-term Employment Contracts in Science” (Wissenschaftszeitvertragsgesetz – WissZeitVG) limits the duration of early and mid-career jobs (Jongmanns 2011, 1). The extension of fixed-term contracts in pandemic times remains an optional provision (Kann-Bestimmung) and not legally binding.