Learning Medical Anthropology through the Coronavirus

5 Student Essays from Copenhagen

Teaching “Introduction into Medical Anthropology” in the Midst of an Unfolding Pandemic

By Anna Mann

At the Department of Anthropology in Copenhagen, like in many other places, a course “Introduction into Medical Anthropology” started at beginning of February. Each Friday, we, a group of engaged BA and MA students and one lecturer, met to become puzzled and learn/teach about concepts to grasp health, illness and healing in its social and cultural context.

While we progressed from Evans-Pritchard to Lévi-Strauss to Mol and Mattingly, we witnessed at the same time how “the coronavirus” emerged around us. From one week to another the cough that one of the students had was no longer innocent, but made her write an email to the lecturer asking whether she was still allowed to come to class. One of the Italian exchange students excitingly announced that she might send us pictures from “the red zone” in which her parents lived and which she planned to visit the following week. But she never went there due to the increasing spread of the virus. And when the Danish prime minister announced on the evening of the 11th March that the universities would be locked down from the next day 17:00 o’clock onwards, we realized that the class on the 6th March had been our last one with physical contact.

Anti-Covid-19 measures by the Danish government in front of our department in Copenhagen, 6 March 2020. Copyright: Anna Mann.

However, “the coronavirus” was not only a phenomenon that affected our daily lives. With the recently discussed anthropological concepts and tools, we recognized how it also was a phenomenon through which scientific facts, illness and health, prevention and cure, the nation state and citizenship became and are still becoming reconfigured. Wasn’t this what medical anthropology is all about? Like lecturer elsewhere, I changed the obligatory readings and assignments and offered the students the possibility to write an essay on “something” related to the coronavirus. Five essays have resulted from this, which, I hope you will enjoy reading.

Wherever you are, stay safe and take care there.

Anna Mann is a PostDoc researcher at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Copenhagen. She currently investigates the crafting of “quality of life” for people, who have been diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, in everyday life and medical practices in Austria. Her work contributes to ongoing discussions in medical anthropology and science and technology studies on care, the good, and living with chronic disease. Mail: am@anthro.ku.dk

The Coronavirus in the Welfare State

By Julia Haugaard

When the Danish government started taking initiatives in order to contain the spread of the coronavirus it was with appeals to classical social democratic values such as the community spirit, and social solidarity. In this essay, I explore how the government’s reaction to Covid-19 can reveal something about state-citizen relations and the legacy of the social welfare system.

[read more]

On a press conference on Wednesday, 11 March the Danish Prime Minister announced that all public employees without critical functions were to be sent home, educational institutions and day-care institutions were to shut down, and gatherings of more than 100 people were prohibited in order to contain the spread of the coronavirus. Furthermore, all cultural institutions, libraries and pastime offers were shut down, and the private sector was encouraged to let employees work from home or take holiday leave. And this was just the beginning. On 13 March, Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod encouraged all Danish citizens who were abroad to return to Denmark:

“We have taken some striking and unprecedented initiatives, and that is to make sure that Danes who are abroad on travels can come home as soon as possible and can come home safe and sound” (my translation).

In line with the Prime Minister, Jeppe Kofod discouraged all travel activities that were not strictly necessary. Furthermore, the government decided to close the Danish border, meaning that persons traveling into the country should expect to be rejected at the Danish border on mainland as well as in the Danish airports unless they live or work in Denmark or are delivering products to Denmark.

“We have to stand together, by keeping each other at distance. We will need community spirit. We will need helpfulness. And I want to thank all citizens, companies, volunteer organizations, persons in charge of arrangements. Everyone, who up to now has shown, that this is exactly what we have in Denmark – community spirit”, was the announcement from the Prime Minister on one of the first press conferences concerning Covid-19.

By appealing to traditional social democratic values of social solidarity and community spirit, the government attempted to create not only citizen support for their new policies, but they also appealed to individual responsibility towards the collective good. Since this appeal, 10.000 people with health-related professional backgrounds have signed up as volunteers to assist the Danish public health system if they will require additional workforce in order to handle the coronavirus. The day after the announced closure of the Danish border, one of the top five most read articles on the public news-media DR (Danish Radio), was about a Danish influencer, Johanne Kohlmetz, who had spent 27.000 Danish crowns (approximately 3.600 euro) on a flight ticket from Mexico to Denmark. Kohlmetz had decided to cancel the remaining one and a half month of her holiday in order to comply with recommendations from the government for Danish citizens to return home. “It was a rough decision, but it was the right one,” Kohlmetz was quoted.

On a personal level, I experienced the compliance with government recommendations as well. A dinner for five people was cancelled, as well as a birthday party for fifteen. A larger party, where 70 people were invited, was broken down to slots, where guests could visit the host at a maximum of ten persons at a time. All in spite of the fact that it was at the current time recommended that gatherings larger than 100 persons should be cancelled. As the Prime Minister said in her speech on 11 March; “We Danes usually seek community and cohesion. Now we must stand together by keeping our distance. We need community spirit and helpfulness” (my translation). I argue that this social solidarity does not solely reflect a commitment to take care of the people in our local surroundings. I propose that the initiatives people take to secure their local surroundings (such as the way in which people act and move in the public and private space to exert caution) reflects the commitment that people as citizens feel towards the state. The compliance to current recommendations, and the initiative from individuals to act responsibly, and succumb and enhance state recommendations points to a high amount of trust in the Danish state from the individual citizen. When citizens face crises that are as incomprehensible as a global pandemic, they rely on the trust in the knowledge, action, and recommendations that the government provides. I argue that it is due to the legacy of the social welfare state that citizens in Denmark have exhibited a high amount of trust in the government, which in turn has resulted in a high level of individual compliance, and proud announcements from people on social media, showing that we are doing our part.

The municipality put up one-way road signs, for runners and pedestrians in the center of Copenhagen. The lakes on a morning run. Photo: Julia Haugaard.

According to Insa Lee Koch (2018), anthropologists of citizenship have argued that official policies which see people as individualized actors often do not sit well with the more relational, emotional understandings that people bring to the picture (Koch 2018:83). It is important, she argues, to acknowledge the ways in which social relations frame a person’s understanding of self and value (ibid.:). In relation to this I argue that the appeal to social democratic values such as the communal spirit the Danish government has succeeded in creating a narrative where individuals become people of value by complying to government regulations. In this case, rather than using personal relations to create meaning, individuals practice social distancing in order to enhance self and value; both in order to secure local surroundings and loved ones and to comply with what the government deems best for the population at large.

Social distancing also entails keeping social relations outdoors and keeping a distance in order to prevent the virus from spreading. Picture from a cold but sunny Saturday at ‘Amager Fælled’. Photo: Julia Haugaard. Published with permission.

Thus, the fight of the coronavirus in Denmark reflects not only a concern for local surroundings and contamination, but a concern with, and the feeling of taking a part in, the Danish welfare state. “As per Max Weber, the state was that which commands a monopoly over legitimate violence (…), the state [can also be seen as] that which commands a monopoly on legitimate personhood and the social interactions that come with it”, writes Koch (Ibid.: 84). I argue that this is exactly what we have seen in relation to state-citizen initiatives on fighting the coronavirus. The legacy of social solidarity in the welfare state has shown how solidarity and compliance are exhibited through individual action, in the attempt to comply with ideas of citizenship, as they are idealized by the state. In the coming weeks it will become apparent how the state-citizen relation will succumb to further, and harsher restrictions of personal freedom.

Bibliography

Koch, Insa Lee (2018) Personalizing the State: An Anthropology of Law, Politics, and Welfare in Austerity Britain. Oxford University Press.

Julia Haugaard is an anthropology student at the University of Copenhagen (UCPH). She has lived and studied in Copenhagen since 2014. Mail: juha@sund.ku.dk

[/read]

“Fratelli d’Italia, l’Italia s’è desta!”[1]

The Awakening of a new Italian Nationalistic Sentiment in Facing the Covid-19 Pandemic

By Simona Bianchi

“Let’s wave proudly our “Tricolore”. Let’s intone fiercely our national anthem. Unite, responsible, brave”

Giuseppe Conte, Italian Prime Minister[2]

People hanging the Italian national flag out of their windows in various Italian cities. Source: Twitter: @massc0, Last access: 27/04/2020

Introduction: #Unitimalontani (united at distance)

“Belonging and being belonged. We are a people of artists and we should never forget about it”.[3]

Italy, 13 March 2020, 6pm. The sun is slowly setting on a ghost-like country. But a sudden, unexpected noise re-awakes people’s terrified hearts: it is more than a voice, more than a call, more than a song… “Fratelli d’Italia”, the national anthem, resounds through the emptiness of Italian cities, shading a new light on the up-coming darkness of the night.

[read more]

Those are dreadful days for Italy and the Italian people. The country reported 199,414 cases on the 27 April, and up to 26,977 deaths. Numbers that nobody wants to see. It is dreadful. Since 11 March all the non-essential shops and meeting spaces have been shut down. Only grocery shops and pharmacies remain open. Roads are empty, bars, restaurants, schools, museums, cinemas… all empty. Cities resemble a romantic painting: solitude and desolation have become the main characters. But this emptiness is only the illusion of a mute picture. In fact, at late noon, this spatial vacuum reveals its hidden vibrant life. People, responding to the hashtag #unitimalontani (close but far away), sing loudly from their windows filling in the emptiness of the surrounding night. The campaign was inaugurated on 13 March and the opening song was the national anthem. That evening Alessio Zucchini, an Italian reporter, commented on the daily TV news: “the anthem, for driving away the fear, for feeling closer even though we have to stay at distance. “Mameli” [the anthem’s title] bounds an Italy looking for a new ‘Risorgimento’[4]”.

Together we can do it!

Singing is not the only initiative to fill in the spatial emptiness, “exorcise the fear and feel less lonely”. Indeed, various are the creative ways through which some people in Italy try to overcome the isolation and desolation of those days. Balconies and windows speak through hanged banners displaying encouraging sentences. “Everything will be fine”, “together we can do it” they say. But, as the image below demonstrates, almost everything can communicate sympathy.

Diaper saying “everything will be fine”. Post by the Facebook page of the Neonatology Association of the Niguarda Hospital (NEO) in Milan (IT) @NEOamicineonatologia, Last Access: 27/04/2020

The mutual support expressed by those banners is, at first, very moving. Yet, a second, slightly more implicit message is also hidden in it: the awakening of a new nationalistic sentiment. The massive reproduction of the national flag, the “Tricolore”, as well as the repetitive use of its colors, green white and red, for decorative purposes is paradigmatic. Furthermore, sentences are written in the first person plural, the all-encompassing “we”. It includes all the Italians, who, though forced to stay at home, still express the will to be “together”. They imagine to be united despite the distance. This scenario describes very well how a nation is, in Anderson’s words, an imagined community (Anderson 1983). He defines a community as a homogenous group of people, whereas by ‘imagined’ he refers to “the actuality of even the smallest nation exceeds what it is possible for a single person to know”. For instance, a person cannot know every aspect of the nation economy, geography, history… and, above all, each fellow compatriot (Anderson 1983). Indeed, none of the singers nor of the banners’ authors know all the others. Yet, each of them perceive to be part of the same, homogeneous group of people, that is a community.

Anderson’s study on the birth of nations and nation-states may further help in understanding the re-awakening and the diffusion of the national sentiment. In his analysis he focuses on the paramount role played by the establishment of print culture, particularly focusing on the newspaper distribution. Indeed, newspapers not only consolidated a common language, but they also “shorten the distances” within the national territory. Every morning, a person could read nation-wide news, sympathizing with those, kilometers away, experience harsh situations (Anderson 1983). In the days of Covid-19, to overcome a new kind of territorial distance, new means have been deployed: social networks. Saying that social networks outpaced newspapers as main tools for diffusing information is nothing new. But what is at stake here is unveiling their role in connecting a community, precisely as newspapers used to. The outbreak of Covid-19 is certainly a dramatic situation, and people all around Italy are sympathizing with one another through the social networks. They share stories of illness and send messages of support. This continuous posting, re-posting, commenting on the virus allows the community to feel closer, despite the territorial, physical distance. Therefore, acting as a tool of communication, social networks trigger a communitarian feeling, which leads to a newly born national intimacy. Italians are now perceiving themselves as a new imagined community.

United against a common, invisible enemy

The popular initiative has been strongly appreciated and supported by various Italian politicians. For instance, the Vice-Minister for Health, commenting on people singing the anthem, thanked “each responsible citizen” and all of them who “fight against this war we will win”. Our windows and balconies are the best showcases to communicate our strength”. Words that are particularly powerful in delivering a nationalistic message. First he addresses Italian citizens directly, stressing the importance of each one. Then he refers to them with the first person plural pronoun (we/our), expressing how they are part of a single entity. In his words, a unified Italy can defeat the virus by showing a single strength resulting from the sum of those of each citizen.

But, if compared with other politicians’ sentences, this quote shows a common trend which deserves further consideration. That is the combination of the rhetoric “us” with a warfare scenario. Indeed, political figures are continuously inviting the Italians to come together to fight and defeat a common enemy. As Daniele Cassandro clearly demonstrates, metaphors of war have largely been deployed to describe diseases in general. For instance, he quotes people “defeating cancer”, or “fighting AIDS”. What his article obscures is the collective dimension that is invoked by those metaphors in the case of Covid-19. Particularly, the communitarian sentiment arises from the perception of a common enemy. Indeed, as Marie Becker concludes in her paper for the Harvard political review, the presence of a common enemy propels people to “unite around a common goal”. In the quote from the Vice-Health Minister, sentences are clearly structured to bring people together [we], under the common goal of fighting a common enemy. Even more emblematic is the Facebook post that Giuseppe Conte, the Italian Prime Minister, wrote on the Italian Unity day, 17 March: “We are the State: sixty millions of citizens fighting together, with strength and courage, to defeat this invisible enemy”. It describes a state, identified with the imagined Italian community (“we”), that has been invaded. In order to free itself and defeat its enemy, it calls for the unification of the whole people.

Those two examples clarify how the politicians’ rhetoric, by identifying a common enemy and goal, is claiming for national unity. In this way, it sustains and increases the new social intimacy I previously outlined. Indeed, Conte concludes: “As never before, Italy has to be united”.

“Forza Italia”, the international recognition

During the past few nights, the world seems to have become Italian. Major cities around the globe lightened their main monuments with the colors of the “Tricolore” (below, fig 4). From Jerusalem to Dubai, different countries have declared “Italy, we stand with you” [5]. As different media describe it, the main message of this initiative is the international will to support a now suffering nation. Evidently, these supportive gestures also deploy a marked nationalistic rhetoric. Indeed, highlighted monuments show the massive use of the flag colors, representing the Italian nation.

Worldwide cities or famous places displaying the Italian flag colors. Source: Nursetimes.org, Last Access: 27/04/2020

But the rhetoric stems also from pictures circulating on social media. For instance, an image on Facebook portrays Italy sustained by two physicians, one with an “Italian” medical coat, the other with a Chinese one. The scene clearly speaks accordingly to the nation-state rhetoric. The whole Chinese people is helping Italy alongside with the Italian one. Both are recognized to be different from the other, yet internally homogeneous.

Italy sustained by two physicians with an Italian and a Chinese coat respectively.Source: Aurora Cantone @aurs_artt,. Last access: 25/04/2020

What those two examples display is the importance of international recognition of a nation-state. As Tilly masterfully demonstrates, in order to really exist, a nation-state requires to be recognized by other comparable organizations, that is to say other states (Tilly 1990). With this in mind, the powerfulness of the international action in strengthening the Italian nationalism becomes clear. It is not only expressing empathy towards a group of people. Most importantly, it is asserting that those people are recognizable under the label of “Italy”, a unified nation-state.

Conclusive remarks

The Italian situation is dreadful. The fear of “the invisible enemy” flies over the entire Italian landscape. The painful but necessary precaution measures compel an almost total physical distance. Yet, as the examples I presented show, this physical distance is triggering the rebirth of a nationalistic spirit. This new “Risorgimento”, I argued, is sustained on three different levels: the social, the national, and the international, all of them reinforcing the idea that Italy is a unified and strong nation-state. On the social level, what emerges is the idea of a new imagined community. People all over the country feel bounded to one another, empathically sharing mutual support and suffering. On the nation-state/institutional level, the focus shifts towards representations of a common enemy and a common goal. Having identified them, politicians call for national unity, thus reinforcing the social intimacy. The international scenario offers another important insight. Other nation-states recognize Italy as a unified entity, which has a specific place between other single unities. This recognition, reflected into posts share on social networks, is further empowering the new Italian nationalism.

Simona Bianchi is a bachelor student in anthropology at the Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Italy. She is currently attending an exchange program at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, where she deepened the study of medical, political and economic anthropology. Mail: simona.bianchi6@studio.unibo.it

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London, Verso editor.

Tilly, Charles. 1990. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1990. Cambridge. Basil Blackwell editor

Footnotes

[1] “Italian Brothers, Italy has awaken”. It is the opening verse of the national anthem.

[2] My translation

[3] “Appartenere ed appartenersi. Siamo un popolo di artisti, non dobbiamo dimenticarlo”. Lorenzo Cioce, the author of the sentence, is a young poet living in Rome. He pronounced those words when interviewed by Rainews about people singing the anthem, see bibliographical reference. My translation.

[4] The word indicates the period of the Italian national unification struggle. It literary means re-born, re-awaken.

[5] The sentence was projected on the Jerusalem wall.

[/read]

How the Corona Crisis brings Guilt and Blame into our Everyday Lives. Reflections on Social Interactions in Danish Society during the Pandemic

By Johanna Louise Skovsende

The coronavirus comes with new social codes. In Denmark the word “samfundssind”, that loosely translates to social solidarity, sets the tone for many of the current norms and ideals. “Stay home, keep a distance, show samfundssind” is frequently heard in the Prime Ministers’ press conferences, in news articles and on social media. In the Danish newspaper Politiken, a journalist appeals to make samfundssind the word of the year:

“It is now that we, as average citizens, have to choose the persons we want to see in the mirror until the pandemic eventually runs out and the world returns to normal […]” (my translation)

As stated in the article, samfundssind is about showing our worth as citizens in this challenging time and while it constitutes a positive message in a time of crisis – we are fighting a common enemy in solidarity – it also injects uncertainty, guilt and blame into our social interactions. This is my experiences as a Danish student living in Copenhagen.

[read more]

Public signs in Copenhagen illustrating health regulations. Copyright: Johanna Skovsende

Public signs in Copenhagen illustrating health regulations. Copyright: Johanna Skovsende

Collective guilt

The Danish newspaper Weekendavisen carried an interview with anthropologist Karen Lisa Salamon in which she states that collective guilt has returned to the Danish society during the corona crisis. Illness is no longer a personal matter and we are held more responsible for each other’s health. It is comparable to previous cases of tuberculosis and syphilis. This shift from tending individual interests to prioritize societal needs is apparent in the word samfundssind.

The increased guilt and samfundssind might have positive implications for society; perhaps it will transfer to attitudes towards crises like climate change which we have a notoriously hard time taking collective responsibility for. From my perspective, however, it seems like the collective guilt has entered our everyday communication as an increased blame-gaming.

The everyday blame-gaming

Besides the angry looks you might get if you sneeze or cough in the grocery store, the blame-game mostly prevails on social media platforms:

“If one does not bother to comply with the authorities’ advice to keep a distance, to cough into the elbows […] – then it may cost your own grandfather’s life or someone else’s grandmother.” (post on my Facebook feed my translation).

This post mirrors many of the social media statuses and comments that I have come across since the pandemic accelerated. Every day, news stories are published about people who fail to follow the restrictions. A hairdresser kept his salon open for customers all night the day before all shops with physical contact were required to close. According to an article, the shop’s Facebook page overflowed with people criticizing the hairdresser’s decision. A mother and her two children went to a playground without knowing it was closed and they got a ticket from the police. It blew up in the media, and the countless comments to the article on social media were mixed: some thought it was unfair, most people were outraged and angry at the woman.

Those who do not conform to the social norms connected to samfundssind are to be blamed. We keep a more vigilant eye of each other, watching to ensure that our neighbor, the cashier at the grocery store or even our friends follow the rules. A lot of us are more inclined to point fingers. We also examine our behavior and direct the blame towards ourselves and we might be unsure if we are doing the right or the wrong thing. This all might have something to do with this pandemic being a crisis of uncertainty.

Moral uncertainty

Health regulations are constantly mediated to the Danish public, and they change constantly as scientists learn more about the virus. The categories of right and wrong are not fixed. The word samfundssind is used in many of the different, sometimes conflicting messages. We have to choose and navigate in different values. In some cases, people themselves have to draw the lines between good and bad, between practicing samfundssind and being a bad citizen.

We are trying to be good citizens without exactly knowing how that is achieved. The handbook on fighting pandemics does not exist. All we know for a fact is that we are all complicit in and collectively guilty of the spread of the virus. Being painfully aware of this, while not knowing the way out, creates tensions of blame and guilt in our social interactions.

In this way, the social effect of the coronavirus is twofold: the pandemic enhances solidarity and moral citizenship encapsulated in the Danish word samfundssind. The collective guilt brings blame into society and it is strengthened by a moral uncertainty. I will be interesting to see if the collective guilt persists when all of this is over and how it will affect our post-Corona everyday life.

Johanna Louise Skovsende is a third-year BA student of Anthropology at University of Copenhagen. Her essay is conducted as a part of the course Introduction to Medical Anthropology. Mail: rxb908@alumni.ku.dk

[/read]

Italian Narratives about Medical Staff during Covid-19 Emergency

By Giorgia Govi

Introduction

During the last weeks, medical staff who work in hospitals in Italy have become a crucial figure in the Italian fight against coronavirus’ spread throughout the country. Their importance was recognized also before this difficult situation, but now doctors, nurses and health professionals in general are considered by the Italian population as heroes. I wish to investigate how these narratives are constructed by considering how the incessant labor of the Italian medical staff is perceived by the country’s population. For doing so pictures and quotes taken from social media, both uploaded by nurses and other citizens, will be used. I will also link these narratives to the work of Somatosphere’s blog, which recently has focused on coronavirus’ issue, from an anthropological point of view.

[read more]

Italian citizens’ narratives about health workers’ commitment

In Italy, citizens are obliged to remain at home and they are only allowed to leave their houses for short periods, with a valid certification that attests where the person is going and why he or she is outside. This scenario is due to the rigid measures that the Italian government has taken in the last weeks in the attempt to slow down and stop the spread of coronavirus in the country. The number of people that are infected by the virus grows day by day, and so does the amount of people who need to be cured in the hospitals. Starting from this assumption it is not hard to imagine why medical staff who work inside Italian hospitals are considered, now more than ever, heroes.

The harsh situation that health professionals face due to the high number of patients they have to treat oblige them to sleep less, to eat during the few and really short breaks, and to be constantly exposed to the virus.

In Reggio Emilia, located in Northern Italy, citizens have demonstrated their esteem to the medical staff that works in the hospitals of the city and province during the last few days. One of these manifestations of respect and admiration for health professionals’ labor consisted of food brought to the hospital: “Food is more than just nourishment. It is comfort, it is staying together. Also remotely”. Ordinary citizens bring biscuits, pizzas and other gifts to the medical personnel in order to express their proximity to the work of the medical staff: “I can not give my contribution in another way, but I am with all of you”, a card cited. The population is aware of the crucial role that medical professionals play in this emergency situation, and this awareness is expressed by small, but appreciated gestures that manifest their concern about medical staff’s lives.

Similar expressions of proximity and esteem towards health professionals occurred, and are still happening, all over Italy. “It is a sanitary emergency, but it seems a World Cup, with the Tricolor at the windows, the encouragements and the rounds of applauses from the balconies”.

The initiative has emerged in the Facebook group “Applaudiamo l’Italia” (“We applaud Italy”), as an opportunity to encourage and show respect and vicinity to anyone who is working to get the country well again. These manifestations are also directed to medical staff all over the country.

The picture shows a physician that stands in front of coronavirus. The author of the drawing intends to thank medical staff’s commitment to protecting and “saving” society from Covid-19. @milomanara_official, Last accessed: 27/04/2020.

The reaction of Italian citizens is also due to the pictures that some doctors and nurses are posting on Instagram or Facebook. These photos show parts of the staff who are sleeping, exhausted, after an infinite work shift, health professionals who can not eat, drink, or go to the bathroom for hours etc. The reason why these physicians are posting such pictures is not that they want to be considered as heroes, but because they hope to give Italians the moral liability to stay at home, because the situation is already critical, and the hospitals are going to collapse soon.

The drawing shows a nurse lulling Italy as a newborn child. @francorivolliart, Last accessed: 27/04/2020.

The population’s response to this harsh situation consists of billboards and signs hanging outside the windows of the houses, in public spaces or outside the hospitals. Some of them quote “everything will be fine”. But some people also have drawn pictures of these professional figures, depicting them facing the coronavirus or helping patients to get better.

One of the most shared drawings on the web represents a nurse, depicted with a pair of angel-wings, with a mask and in the act of lulling a red Italy (the country was declared red zone because of the fast spread of the virus) that is partially covered by the Italian Tricolor.

A comparison between new narratives about medical staff in Italy and China

For the analysis of the new narratives that Italian citizens are constructing around the figures of health professionals I have considered the reflections present in the website “Somatosphere”. In particular, I have found interesting the research conducted by Frédéric Keck, in which the author takes in consideration how Chinese propaganda, during February 2020, enforced the figure of the “barefoot doctor”, who is ready to fight and sacrifices himself in order to defeat a common enemy, in this case, coronavirus. “Chinese propaganda enforces this discourse of sacrifice: physicians sacrifice themselves for the rest of the society” (ibid.).

I think that a comparison between this metaphorical representation of physicians’ work in China and the consideration of the health professionals’ figures in Italy can be easily traced. In both cases they sacrifice themselves for a common cause: the safeguard of citizens and their health. Both in China and Italy, physicians are considered heroes thanks to the pivotal role that they have in defeating the worse community’s enemy, which is the virus. In the Italian case, such as the Chinese one, the government has constructed a precise interpretation of medical staff’s figures and their work, by calling them “heroes”. An example of this narrative is the Facebook post that the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte wrote at the end of March, where he thanked all the “heroes in white” and highlighted their crucial role in the safeguard of the country.

The main difference that can be drawn between the Chinese and the Italian cases is that in China the figure of the “barefoot doctor” is not just a metaphorical construction, but it is a real figure introduced during the second half of the 20th century. This figure was meant to provide a basic health care system in rural areas of the country and rescue poor peasants, and in order to do so “doctors had to cast away their self, smash privilege and merge with the masses” (Lynteris, 2013: 100). But the “barefoot doctor” has become a symbol on which several narratives about heroic work are built, as Keck points out. Conversely, the narrative concerning medical staff as heroes in Italy is quite recent, and it is traced back to the arrival of the pandemic. As the article “Doctors: always accused, but heroes at the time of Covid-19” underlines, before the spreading of the virus medical staff were often criticized for doing an insufficient job. On the contrary, during the period of emergency they soon became considered as professionals aware of the risks and dangers of their work, but always ready to save patients.

Conclusion and final reflection

For the previous reflection about the narratives constructed around figures that belong to medical staff, I used principally local newspapers’ articles, pictures and reflections posted on social networks because I consider them a more direct expression of people’s feelings towards the topic.

With this short comment I wanted to highlight that these new narratives are not exclusive of Italy and its present situation, but that it is interesting to see how Italian people honor medical staffs’ work and commitment through drawings, food supplies, banners and applauses from their houses. It seems noteworthy that citizens feel the urge to underline the medical staff’s strength, even when they could simply think “It’s their job, they have to do it”.

“We call them heroes, and we are right”.

Bibliography

Lynteris, Christos. 2013. The Spirit of Selflessness in Maoist China: Socialist Medicine and the New Man. University of Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan.

Giorgia Govi is an undergraduate student of Anthropology at the Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Italy. She is currently attending an exchange program at the Department of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Mail: giorgia.govi@studio.unibo.it

[/read]

COVID-19 and the Starvation of Information it feeds into

By Anne Sofie Beer

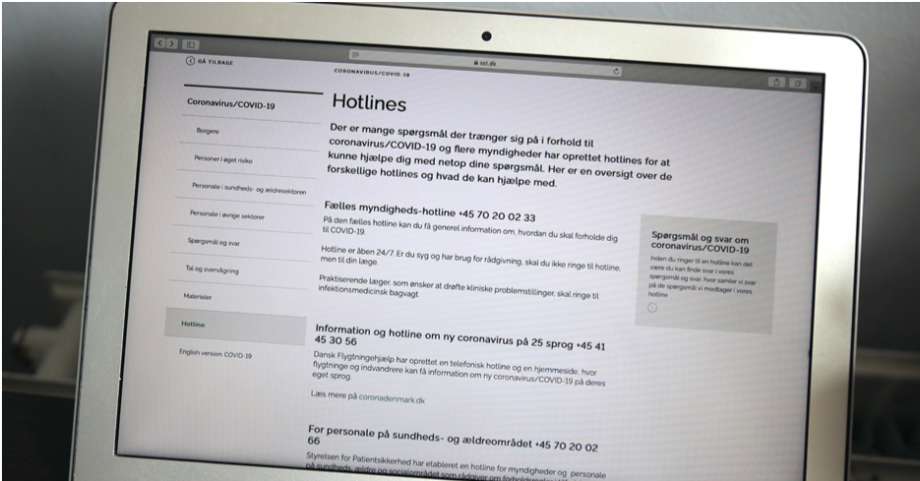

In light of the COVID-19, Danes have become information-starving (informationshungrende), one article suggests. This is evident in the way webpages from official authorities such as the Danish Health and Medicine Authority and the Police have crashed on more than one occasion due to increased access rates (ibid.). Moreover, a national corona-hotline has been established, in which people can pose all their COVID-19 related questions. This also relates to the numerous articles in which experts answer questions such as: Can we still throw a family birthday party? Can my children play with other children? Am I allowed to give my husband a hug? Can we go to a restaurant? Is it possible to get contaminated from the milk carton in the supermarket? Moreover, both TV2 and DR, the biggest television broadcasters in Denmark, offer live updates on the pandemic. The reason for this great request for information is simply that: ”We want certainty in an uncertain situation.”, as an article concludes.

[read more]

A disposable glove, an increasingly common sight in the streets of Copenhagen. Copyright: Anne Sofie Beer

I wish to draw attention to historian Lukas Engelmann’s (2020) concern that historically there has always been a delay between the emergence of an epidemic and the establishment of an agreed-upon representation of its scale and dynamic. Engelmann contrasts this to the near real-time surveillance of COVID-19, that “delivers a dangerous sense of oversight and certainty” (ibid.: 2). The surveillance of COVID-19 thus creates a sense of history being written daily, if not hourly on social media, he adds. This point is interesting in relation to the response from the Danish government. The government announced a two-week shutdown based on a strategy of putting less pressure on the Health Care System by increasing the time frame of which people get the disease. A strategy that is clearly based on statistical data enabling a prediction of the development of the epidemic. Engelmann problematizes attempts to make sense of an epidemic while still in the thick of it. He warns of how pictures, maps, curves and figures of the epidemic are based on a few routinely used models that reduce complexity and simplify social mechanics. A consequence is that these “simulations of possible epidemics” appear as real representations on which political actions are based (ibid.: 3).

I find the hourly surveillance and the oversight it ‘creates’ interesting in relation to the information-starving Danes, who are clearly not satisfied by the information overload already available. Although this information is clearly efficient for the Danish government to take radical political action; the Danes are so to speak still hungry, rather than being “information-fed up”. Possibly, this relates to the lack of desired information available to the Danes about the disease based on an idea of what information is needed about a virus disease; incubation period, duration of contamination, symptoms and treatment. And in these instances, COVID-19 is challenging in the way that the prior knowledge about the disease lacks. In this sense the disease creates uncertainty, as the article states.

The COVID-19 Hotline established by the Danish Health and Medicine Authority. Copyright: Anne Sofie Beer

However, the need for information is not a self-given. It is a product of the access to networked digital technologies such as social media. Hyunjin Seo (2014:151) argues that these new communication channels enable citizens to participate in activities traditionally reserved for authorities which has ultimately changed the cultural practice of public communication.

This access to communication has removed the gatekeepers of the information distribution, but perhaps also of information demand? The hunger for information is reinforced by these technologies available, while people become accustomed to the hourly surveillance. In Denmark, it is actually made possible to call a ‘corona-hotline’ and to ask professionals offering to answer through various newspapers. And if people did not seek the information beforehand, they are yet exposed to questions about everyday actions that potentially makes them question their daily activities and responses to the COVID-19. Hence, the technologies such as live updates, hotlines and informative videos are also part of the production of this need – this information-starvation- that they are created to fulfill. In drawing this connection, I echo the stance of Rogvi et. Al. (2016), in their argument on how technologies potentially participate in creating the problems they are intended to solve (Rogvi et. Al. 2016:263). They are thus shaping practices in relation to the COVID-19. Not only among those infected, but among the broader public.

Anne Sofie Beer is a master student at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Bibliography

Rogvi, S, A. Juul & H. Langstrup. 2016. Generating Local Needs through Technology: Global Comparisons in Diabetes Quality Management. East Asian Science, Technology and Society 10: 247-267.

Seo, Hyunjin. 2014. Visual Propaganda in the Age of Social Media: An Empirical Analysis of Twitter Images During the 2012 Israeli–Hamas Conflict, Visual Communication Quarterly, 21 (3), 150-161.

[/read]