The Futures of Deliberative Democracy

Citizens’ Assemblies as Technocratic Population Management

Introduction[1]

Citizens’ assemblies, planning cells, consensus conferences etc.: Over the past decade these “deliberative mini-publics” have been promoted as the fix for the so-called “crisis of democracy” (Dryzek et al. 2019). The promise is simple and seductive: randomly select a diverse group of people, give them balanced information, facilitate respectful discussion, and out comes a set of informed recommendations or the “true will of the people” that can guide and legitimate policy (Olsen & Trenz 2014).

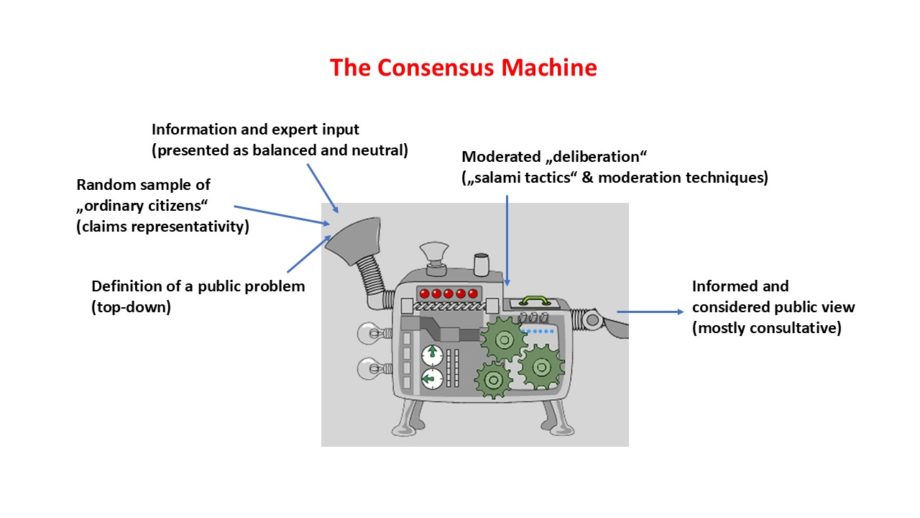

This blog post distills a longer study that analyzes the doing of mini-publics to understand how they are conceptualized, marketed, and enacted. The core argument is that far from their promises of being bottom-up engines of empowerment, contemporary mini-publics often operate as what I call “consensus machines”: carefully orchestrated devices that stabilize existing orders of rule by turning disagreement into manageable consensus (see Image 1).

Fig. 1 The consensus machine, own representation

I explore this idea through three linked praxiographies of: (1) a translocal expert network that promotes and standardizes them as policy instruments; (2) a manual that scripts an idealized form oriented to elite needs; and (3) procedural setups that condense heterogeneous inputs into a small set of consensual outputs. Put differently: what gets celebrated as innovating democracy frequently functions as technologies of technocratic population management.

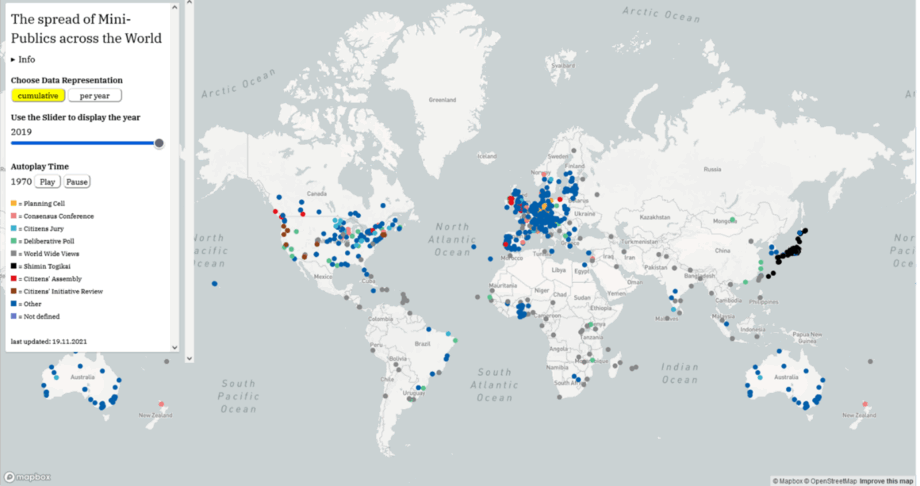

The Lost Consensus

Mini-publics are often presented as an attempt to restore the lost consensus of the 21st century. This idea can be illustrated through Lawrence Lessig’s provocative thesis “How the Net Destroyed Democracy”.[2] According to Lessig, in the 19th century the public sphere (in the US) was fragmented; there was no national media and no polling. The 20th century centralized it: mass media plus surveys manufactured a shared, elite-shaped consensus (for a critique see Herman and Chomsky 2002). Today, the internet and platform logics have fractured this consensus again. Algorithms produce “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” that make publics more polarized and harder to govern (Pariser 2011; Terren & Borge 2021). Against this backdrop, Lessig turns to mini-publics as a remedy. Citing Fishkin’s model of Deliberative Polling, he highlights how mini-publics can bring people back into dialogue, foster common ground, and restore consensus. In this sense, the spread of mini-publics has increased significantly across the world since around 2009 (see Image 2). The set-ups of mini-publics appear very similar almost everywhere in the world (see image 3).

Fig. 2 The spread of mini-publics around the world, screenshot from https://sfb1265.github.io/mini-publics

Fig. 2 The spread of mini-publics around the world, screenshot from https://sfb1265.github.io/mini-publics

Fig. 3 Mini-publics as a translocally circulating model of doing democracy, own composition of publicly available pictures.

Fig. 3 Mini-publics as a translocally circulating model of doing democracy, own composition of publicly available pictures.

Yet, my ethnographic record suggests a managerial turn. Rather than redistributing power from the top to the bottom, contemporary mini-publics help produce a consensual set of policy recommendations that can be presented and amplified as the people’s voice. This critical perspective aligns with scholars such as Wagner’s (2014) “participation trap”, Blühdorn’s (2013) “simulated democracy”, or Petit & Oleart’s (2026) “citizenwashing” that all highlight how deliberative mini-publics, far from empowering citizens, often function as instruments of power that legitimize elites’ policy-making choices while neutralizing dissent.

A Practice-Theoretical Lens

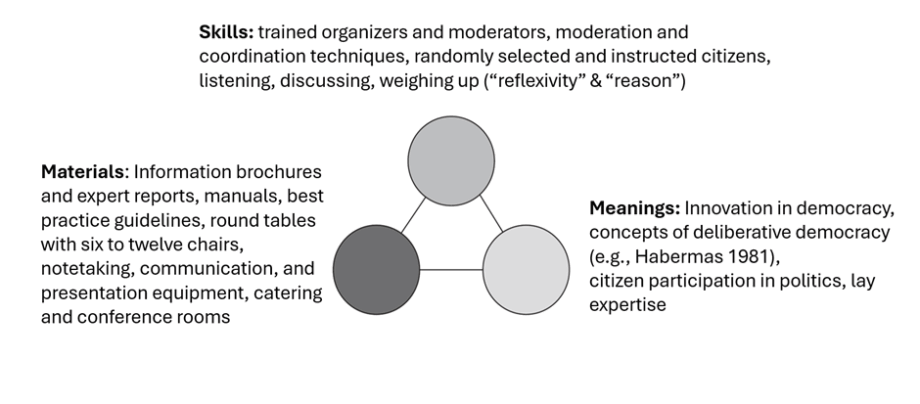

To make sense of how consensus is actually produced instead of simply assumed or normatively justified, a practice-theoretical approach helps understand social practices both as concrete doings and as socio-material arrangements of skills, materials and meanings (Shove, Pantzar, & Watson 2012). Instead of treating mini-publics as “black boxes”, I look at the socio-material elements that compose them (see Image 4):

Fig. 4 Elements of mini-publics, own illustration based on Shove et al. 2012:29

Fig. 4 Elements of mini-publics, own illustration based on Shove et al. 2012:29

As these elements come together, they form a recognizable pattern of practice oriented toward producing a coherent “view of the publics” or “true will of the people” (Olsen & Trenz 2014). This praxiographic lens will clarify why consensual outputs so often look tidy: they are made tidy through agenda setting, framing, selection, clustering, moderation, voting, and time compression. The praxiographic analysis below follows three sites of practice – network, manual, procedure – to show how mini-publics are assembled as consensus machines.

Praxiography Part 1: The Expert Network

In 2018, the expert network Democracy R&D was created and has since grown as the most important player in promoting and harmonizing deliberative mini-publics (Voß et al. 2021). The initiative was spearheaded and initially funded by philanthropist Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, former director of Transfield Holdings, an Australian energy and transportation company. Belgiorno-Nettis had already founded the Australian NGO newDemocracy in 2011 to explore whether “innovation in democracy was possible and to find better ways to let leaders lead and for trusted public decisions to be made” (newDemocracy 2013). This orientation – improving the conditions under which political and economic elites make decisions while maintaining public trust – was carried over directly into the mission of Democracy R&D. Its slogan encapsulates the orientation: “We help decision makers take hard decisions and build public trust” (see Image 5).

Fig. 5 Democracy R&D, own compilation of screenshots on mission, funding, spread, testimonials and group picture from https://democracyrd.org/

Fig. 5 Democracy R&D, own compilation of screenshots on mission, funding, spread, testimonials and group picture from https://democracyrd.org/

Agency is thus clearly oriented top-down, toward strengthening decision-makers and securing governability, rather than empowering citizens from below. The lobbying of the network follows the same logic. The network cultivates ties with mainstream, often conservative politicians, and emphasizes “neutrality” to avoid association with activist groups such as Extinction Rebellion that has also campaigned for citizens’ assemblies. The promise is pragmatic: mini-publics help governments enhance legitimacy and manage difficult policies without ceding decision-making power.

When I attended annual meetings of the Democracy R&D network, the focus of discussion stayed tightly on technical refinements and best practice standards: how to best randomize participant selection, improve facilitation techniques, or write collective reports. Broader questions of inequality and power were bracketed out. This narrowing fits what Rottenburg (2009) calls a techno-functional “metacode”. By translating political questions into technical ones, the network creates a shared language that allows cooperation across borders and contexts (Voß et al. 2021). But it also reduces mini-publics to standardized “plug-ins” for governance that aim at stabilizing and preserving existing institutions and not reforming or replacing them.

Critiques from outside make the technocratic shift visible. Paul Vittles (2020) has described actors such as Democracy R&D as a “Citizens’ Assemblies Lobby” that privileges expert-led, controlled processes over genuine empowerment. He points to how participants are informed but not empowered, how outputs rarely shift policy, and how the small size of assemblies sidelines wider publics (see also Hammond 2021; Lafont 2020). Within the network, however, such criticisms are not seriously debated. They are reframed as design issues – for example, a matter of refining sortition algorithms to minimize selection bias – rather than political questions.

Practice theory helps us see what is happening here. Networks like Democracy R&D are not just neutral spaces for knowledge exchange; they are “instrument constituencies” that exist for and by the policy instrument (Voß & Simons 2014, 738). Through conferences, online forums, and lobbying, they stabilize certain practices, embed routines, and shape what counts as “good” deliberation. Their “structural promises” – jobs, contracts, visibility – consciously or unconsciously ensure that mini-publics adapt to political demand (Simons & Voß 2018): In order for deliberative mini-publics to be commissioned by political authorities, they need to produce predictable results, be time and resource efficient, and enhance the legitimacy of existing authorities and institutions. In this process, the “functional promises” of deliberative democracy as emancipatory transformative processes are transformed to suit the agendas of those who commission them.

The result is that mini-publics do not function as bottom-up empowerment but largely as top-down instruments of governance (Kübler et al. 2020, Hammond 2021, Petit & Oleart 2026). They serve to legitimize rather than challenge existing power structures.

Praxiography Part 2: The Manual

If the network spreads mini-publics, manuals codify an idealized version of the practice (Bueger & Gadinger 2018). One influential document is the handbook “Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy Beyond Elections” (newDemocracy 2019), co-produced with the UN Democracy Fund. What is immediately striking is who the manual addresses. Its audiences are politicians, bureaucrats, and practitioners and not citizens. Citizens appear only as passive figures who “go through” a predesigned process. This underlines the concern that participants are constrained by the roles they are assigned (Felt and Fochler 2010). Agendas are set top-down, roles are pre-scripted, and structural inequalities are left unaddressed. Politicians, by contrast, are reassured that they remain firmly in control: “As a representative you set the agenda and build a framework to listen before you take your decision” (newDemocracy 2019, 32). Another passage promises that “done well, a diverse mix of everyday people will be willing to stand next to those in government and advocate for a decision” (newDemocracy 2019, 30) (see Image 6). Thus, the underlying message is clear: citizens lend legitimacy, but elites make the decisions. Far from threatening representative institutions with reform or replacement, mini-publics are framed as support systems for them.

Fig. 6 The newDemocracy & UNDP manual “Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy Beyond Election”, own compilation of screenshots.

Fig. 6 The newDemocracy & UNDP manual “Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy Beyond Election”, own compilation of screenshots.

The manual further outlines a set of six principles as the foundation for good design. While some emphasize inclusion, informed deliberation, and reflection, others reiterate that politicians should carefully select which questions to share and which to withhold, thereby safeguarding structural power relations. Fundamental political-economic issues of inequality remain excluded from the outset. In effect, mini-publics are staged as bounded exercises of managed participation, not open-ended democratic experiments. Seen through practice theory, the manual works as an inscription device. It codifies procedures, scripts roles, and thereby embeds a technocratic ontology of participation: conflict is translated into managed consensus, and citizens are enrolled to stabilize governance, not to disrupt it.

Praxiography Part 3: The Procedural Structure

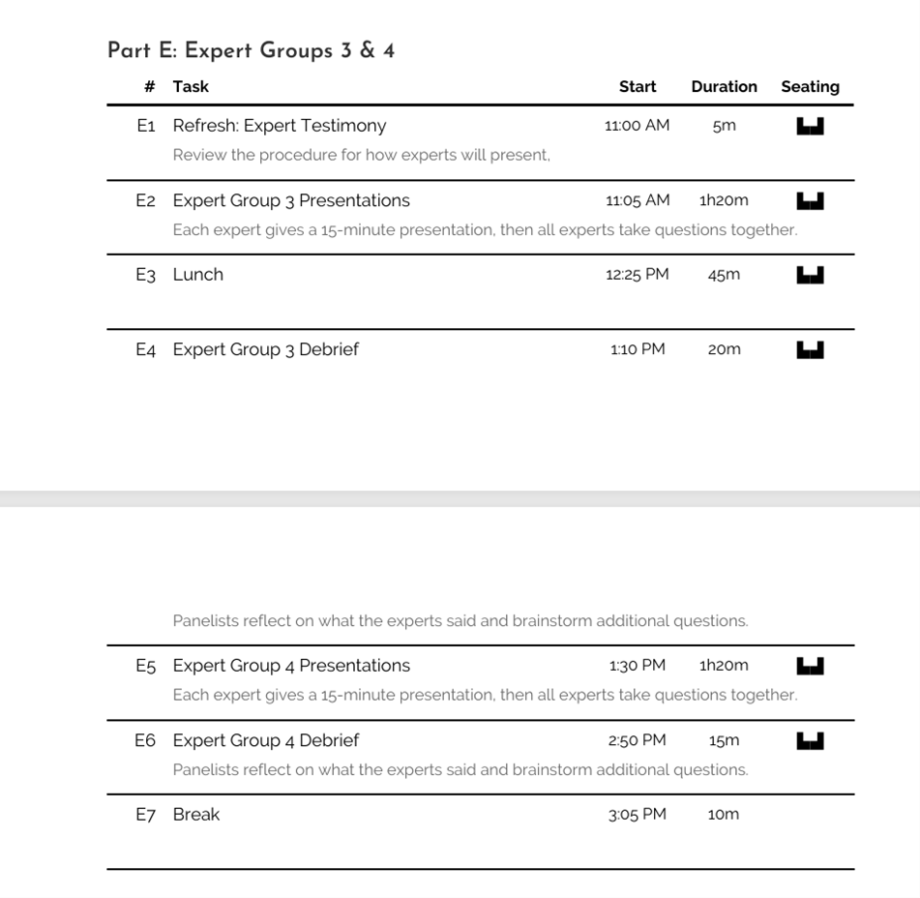

If the network promotes a certain form of mini-publics and manuals inscribe this idealized version, how does the production of consensus manifest itself in real-world processes? From a practice-theoretical perspective, we can explore this question by focusing on the “formative object” (Scheffer 2013): how the final report is an artefact shaped by sequential filtering, socio-material arrangements, and the structuring power of organizers. My sequential observations of six mini-publics show that the outcome is less the “unforced force of the better argument” (Habermas [1981] 2016) than the product of procedural engineering. Consensus is manufactured step by step, through artefacts, facilitation techniques, and time pressures (see Image 7).

Fig. 7 Deliberative processes are meticulously timed. A typical part of the procedural setup includes expert testimonies and subsequent group reflection, screenshot from a citizens’ jury manual.

Fig. 7 Deliberative processes are meticulously timed. A typical part of the procedural setup includes expert testimonies and subsequent group reflection, screenshot from a citizens’ jury manual.

Consensus formation begins even before deliberation starts. Politicians and organizers set the agenda, effectively narrowing possible outcomes (Lang 2009). Neutrality of expert selection, which follows next, is an illusion. In the Scottish Climate Citizens’ Assembly, for instance, Extinction Rebellion activists withdrew from the steering board when their preferred experts were not chosen, exposing how information input predefines the output. Once underway, the process follows the logic of “salami tactics”. Repeated several times, slice-by-slice, ideas are written on sticky notes, clustered, and reduced through preferential voting. At each stage, minority views are sliced away, until only a handful of mostly centrist positions remain. Public dot-voting also amplifies majorities, creating swarm effects. Time pressure then adds another layer. Organizers, moderators and participants are aware that a final report has to be produced in a short period of time. This urgency favors agreement over exploration, sidelining controversy (Felt & Fochler 2010). In some cases, minority reports are allowed, but the main output always crystallizes as a curated, simplified document – sometimes even (pre)written by organizers themselves.

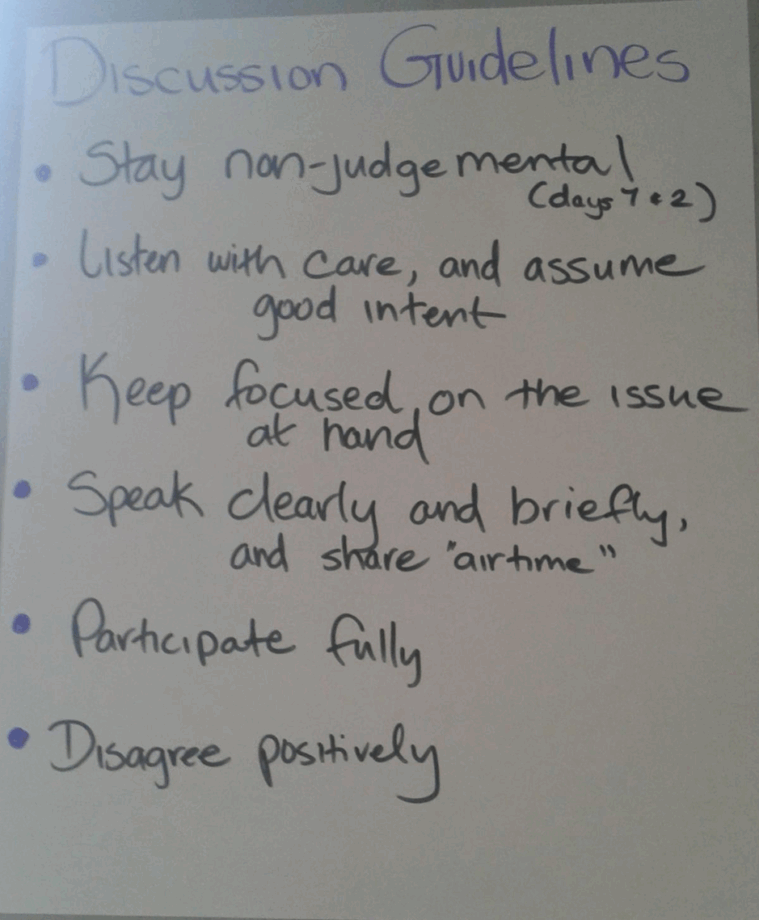

As a result, consensus does not emerge at the discussion tables. Habermas’ “ideal speech situation,” which is to be implemented in reality through discussion guidelines (see photo 8), remains a utopia.

Fig. 8 Discussion guidelines, photo Jannik Schritt

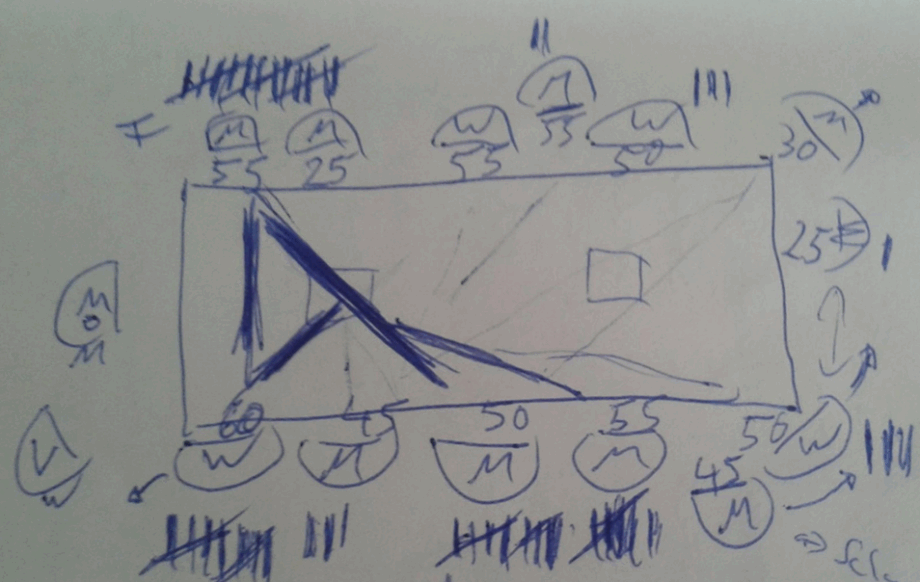

In theory, round seating and facilitation should equalize participation in order for the “forceless force of the better argument” to materialize. In reality, speaking turns are highly uneven (see Image 9). Older, educated men often dominate, while women and less-educated participants speak less.

Fig. 9 Photo of a handwritten visualization of a small group discussion. The sketch shows the gender (M/man & W/women) of the participants, the estimated age (number), the number of contributions (tally marks), and the conversation dynamics (reference lines), Jannik Schritt.

Fig. 9 Photo of a handwritten visualization of a small group discussion. The sketch shows the gender (M/man & W/women) of the participants, the estimated age (number), the number of contributions (tally marks), and the conversation dynamics (reference lines), Jannik Schritt.

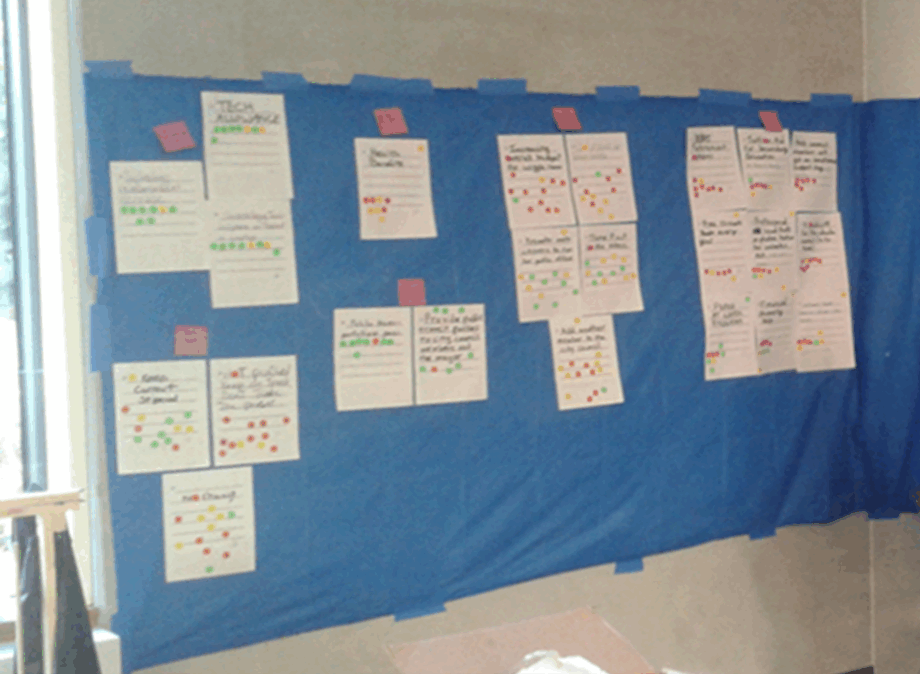

Moreover, moderators and organizers, far from neutral, shape discussions by the moderation techniques of framing, clustering and voting (Landwehr 2014), particularly when under constant time pressure. When participants begin to engage more deeply with an issue, my observations showed that moderators regularly intervene to move things along. Their role is less to foster argumentation than to ensure that something – anything – is written on the cards and posted on the walls. When, for example, the small group discussions went on for a while to exchange arguments without writing anything on the cards, the moderators would quickly ask, a bit impatiently: “What should I write on the card now?” Or they would suggest a keyword themselves that could be used to pinpoint the discussion on the card. The act of writing thus becomes the overriding imperative. Ideas are valuable only once transcribed in brief phrases or keywords. The material device of the card thereby reorients the group’s attention away from sustained debate toward the generation of discrete, recordable outputs. As a rule, there are no lengthy discussions, as both the participants and the moderators are aware that they have to fill their cards in a short amount of time. The cards are then grouped and selected using preferential dot-voting (see photo 10). These steps are repeated several times until a consensus document can be created. The whole logic of the small group discussion is one of brainstorming, input reproduction, completion and voting and not deliberation.

Fig. 10 Clustered and voted recommendations. Green indicates agreement, yellow indicates indecision, red indicates rejection, photo by Jannik Schritt.

Fig. 10 Clustered and voted recommendations. Green indicates agreement, yellow indicates indecision, red indicates rejection, photo by Jannik Schritt.

The picture is clear: mini-publics do not realize Habermas’s communicative ideal. They generate legitimacy by producing the appearance of consensus, but this consensus is the product of engineered practice aimed at stabilizing governability in fragmented societies (Kübler et al. 2020).

Conclusion

Across these three praxiographies – the expert network, the manual, and the procedural structure – a consistent pattern emerges. Mini-publics are celebrated as remedies for the crisis of democracy, but in practice they function as consensus machines. Their institutionalization is driven by structural promises, their manuals codify technocratic roles, and their procedures condense complexity into governable outputs. Seen through practice theory, these are not empowering democratic innovations but socio-material arrangements that reproduce existing orders of rule. They stabilize technocratic governance by turning disagreement into manageable consensus, supporting elites while leaving structural inequalities untouched.

Footnotes

[1] ChatGPT5 was used for language editing (grammar and style corrections)

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHTBQCpNm5o

References

Blühdorn, I. 2013. Simulative Demokratie: Neue Politik nach der postdemokratischen Wende. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Bueger, C., and F. Gadinger. 2018. “Doing Praxiography: Research Strategies, Methods and Techniques.” In International Practice Theory: New Perspectives, 2nd ed., 131–61. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dryzek, J. S., A. Bächtiger, S. Chambers, J. Cohen, J. N. Druckman, A. Felicetti, J. S. Fishkin, et al. 2019. “The Crisis of Democracy and the Science of Deliberation.” Science 363 (6432): 1144–46. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2694

Felt, U., and M. Fochler. 2010. “Machineries for Making Publics: Inscribing and De-Scribing Publics in Public Engagement.” Minerva 48 (3): 219–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-010-9155-x

Habermas, J. (1981) 2016. Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Hammond, M. 2021. “Democratic Innovations after the Post-Democratic Turn: Between Activation and Empowerment.” Critical Policy Studies 15 (2): 174–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2020.1733629

Herman, E. S., and N. Chomsky. 2002. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Kübler, D., P. E. Rochat, S. Y. Woo, and N. van der Heiden. 2020. “Strengthen Governability Rather than Deepen Democracy: Why Local Governments Introduce Participatory Governance.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 86 (3): 409–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318801508

Lafont, C. 2020. Democracy without Shortcuts: A Participatory Conception of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Landwehr, C. 2014. “Facilitating Deliberation: The Role of Impartial Intermediaries in Deliberative Mini-Publics.” In Deliberative Mini-Publics: Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process, edited by K. Grönlund, A. Bächtiger, and M. Setäla, 77–90. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Lang, A. 2009. “Agenda-Setting in Deliberative Forums: Expert Influence and Citizen Autonomy in the British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly.” In Designing Deliberative Democracy, edited by M. E. Warren and H. Pearse, 85–105. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

newDemocracy. 2013. “Founder’s Message.” February 23, 2013. https://www.newdemocracy.com.au/2013/02/23/founder-s-message/

newDemocracy. 2019. Enabling National Initiatives to Take Democracy beyond Elections. Sydney: UN Democracy Fund & newDemocracy Foundation.

Olsen, E. D. H., and H.-J. Trenz. 2014. “From Citizens’ Deliberation to Popular Will Formation? Generating Democratic Legitimacy in Transnational Deliberative Polling.” Political Studies 62 (1_suppl): 117–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12021

Pariser, E. 2011. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. New York: Penguin Press.

Petit, P., and A. Oleart. 2025. “Citizenwashing EU Tech Policy: EU Deliberative Mini-Publics on Virtual Worlds and Artificial Intelligence.” Politics and Governance 14 (1): 10468. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.10468

Rottenburg, R. 2009. Far-Fetched Facts: A Parable of Development Aid. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Scheffer, T. 2013. “Die Trans-sequentielle Analyse – und ihre formativen Objekte.” In Grenzobjekte: Soziale Welten und ihre Übergänge, edited by R. Hörster, S. Köngeter, and B. Müller, 89–114. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. London: Sage.

Simons, A., and J.-P. Voß. 2018. “The Concept of Instrument Constituencies: Accounting for Dynamics and Practices of Knowing Governance.” Policy and Society 37 (1): 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1375248

Terren, L., and R. Borge. 2021. “Echo Chambers on Social Media: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Review of Communication Research 9: 99–118. https://doi.org/10.12840/ISSN.2255-4165.028

Vittles, P. 2020. “Let’s Think Deeply about Citizens’ Assemblies & Citizens’ Juries: Time for Some Healthy Self-Deliberation!” Medium, June 8, 2020. https://paulvittles.medium.com/lets-think-deeply-about-citizens-assemblies-citizens-juries-2038daa37b8d

Voß, J.-P., and N. Amelung. 2016. “Innovating Public Participation Methods: Technoscientization and Reflexive Engagement.” Social Studies of Science 46 (5): 749–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312716641350

Voß, J.-P., and A. Simons. 2014. “Instrument Constituencies and the Supply Side of Policy Innovation: The Social Life of Emissions Trading.” Environmental Politics 23 (5): 735–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.923625

Wagner, T. 2014. Die Mitmachfalle: Bürgerbeteiligung als Herrschaftsinstrument. Cologne: PapyRossa

Jannik Schritt is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Göttingen. His research focuses on political anthropology and its intersection with economic anthropology, as well as science and technology studies. He is interested in political practices and processes as windows into wider societal structures. In his dissertation, he explored the social, political and economic configuration of an oil nation in the making from the ethnographic perspective of the protests around the opening of an oil refinery in Niger. In his postdoctoral research, he has adopted an ethnographic approach to examine the networking of translocal democracy experts and explore the emergence of a new political space. Here, the focus is not on regulation or issue articulation, but on the design, marketing and dissemination of policy instruments as a central component of contemporary political practice.