Vigilantism in western Burkina Faso

Research about a crisis and within a crisis

Today one year ago I took part in my first field research in Burkina Faso[1] on behalf of my research project “Local self-regulation for the establishment of security: vigilante groups in Burkina Faso” at the University of Leipzig. The research focuses on vigilantes in the West African state of Burkina Faso. The project compares two different formations of vigilantes: hunters (dozo) and “self-defence groups” or “guardians of the forest” (koglweogo). The project explores the vigilantes’ activities, ways of self-legitimization and reciprocal liminations.

The following months of my field research were extremely risky for my husband, who accompanied me as research assistant, and I due to the strongly deteriorating security situation. Nevertheless, we managed to make our first contacts in rural western Burkina Faso and had conversations and interviews with the traditional hunters (Dozo) and with members of their opponents the self-defense group Koglweogo. My research about the violent conflict between the two vigilant groups combined with the risk of terrorist attacks and kidnapping is both very dangerous and complex, however I have faced two more uncertainties since 2020.The ongoing SARS-CoV-2pandemic has made my work all the more challenging and furthermore the upcoming election scheduled for the end of November 2020 could lead to violent and even ethnic conflicts or civil war.

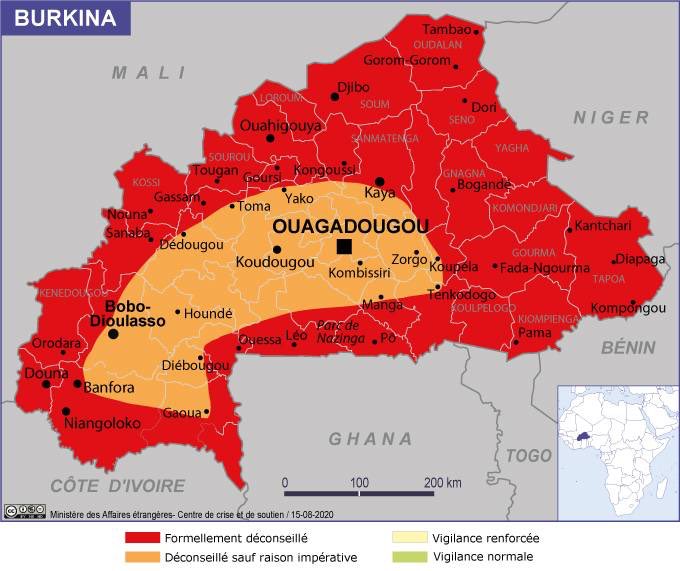

As I write this, I was supposed to do my second fieldtrip in Burkina Faso for three months and a final one in March 2021. My fieldtrip had to be postponed and can only take place in 2021 if there is no major outbreak of SARS-CoV-2[2], which can lead to strict restrictions and the renewed closing of borders. Furthermore, my trip can only take place if the situation remains calm after the elections and if the security situation does not deteriorate further and the Federal Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt) does not issue a full travel warning[2]. The German Embassy in Burkina Faso announced in November 2019 that German citizens are only allowed to leave the capital if they provide a security concept, however their definition is vague. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs advises against almost all travel in Burkina Faso as you can see on the map in figure 1.

Figure 1: Latest travel advice card from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Copyright: Ministère des affaires étrangers).

With all these imponderables, it is very likely that my next fieldtrip will be canceled completely, which will result in a change of my methodological approach and maybe in my topic. Considering the fact that I have already exceeded half of my project duration and my project ends in March 2022, this could confront me with both enormous time and financial problems.

I have already considered alternative research methods to participant observation, discussions and interviews. Due to the low level of digitization in the rural research region, it is more difficult to use social media, such as Facebook and Whatsapp, which are most frequently used in Burkina Faso. Furthermore, my sensitive research topic needs a lot of transparence and trust between myself and the vigilant groups, traditional chiefs, local governance structures and state security forces in the region. Hence a direct, open and respectful research situation is needed. Traditional Hunter in Burkina Faso and West Africa have been well studied and described in the last decades. The creation and spread of the Koglweogo is a recent phenomenon. Therefore, there is very little literature in existence. In case of an annulation of further field research media articles could compensate the lack of sources. Although Burkina Faso has a very pluralistic media society and a satisfactory level of free press, it should be noted that both are still subject to political influence. During the field visit and in discussions with scientists in Burkina Faso I found out that certain media outlets falsified facts or agitated against the Koglweogo and polarized conflicts. Accordingly, media articles about the vigilante groups must be viewed and questioned with the utmost care; a task which is extremely challenging. I would like to discuss this issue with you during the DGSKA autumn school. Are you in a similar situation? How to analyse media articles without falling in the trap of taking everything for granted or by taking someone’s position. How can one best prove without direct contact, if situations happened like they were reported?

Since April 2015 there have been 545 terrorist attacks, in which 1,466 people have been killed and over 507 have been injured with 159 people kidnapped (as of October 3rd, 2020)[3] Since 2017, the violent activities of Islamist groups have increased dramatically, doubling every year. The security situation has deteriorated dramatically in the past three years. In 2019 there was an attack every 1.5 days by Islamist groups moving further and further inland. As of the 8 August 2020, according to National Council for Emergency Relief and Rehabilitation (Conseil national de secours d’urgence et de réhabilitation, CONASUR) statistical data, 1,013,234 people have abandoned their homes for fear of terrorist attacks and potential inter-community conflicts.

By way of international comparison, the SARS-CoV-2rate in Burkina Faso is low. However, there could easily be a major outbreak in Burkina Faso due to the reopened borders, crowds of people in refugee camps and host communities. Election campaign events and during the elections could also provide ample opportunity for SARS-CoV-2to spread rapidly, but also during possible protests or in overcrowded classes in the reopened schools.

Even if it is currently possible to enter Burkina Faso, it is complicated and accompanied by increased costs: Entering Burkina Faso is possible with a negative SARS-CoV-2 test not older than 48 hours. Upon entry, your temperature is measured; if it is high, you are taken to a hotel and are to quarantine until a new test is conducted and that test result is negative. For me and my husband, who, will due to the security situation, also accompany me in further field research, costs can arise from expensive hotel accommodation and multiple tests, which according to the current status are neither covered by my project nor by a health insurance.

Another aspect is that we endanger our health and, above all, our lives due to the security situation if we go into the field again. Nevertheless, I would like to do further research in Burkina Faso in 2021, if possible.

My decision may seem strange to some researchers without any (West) Africa reference or experience. I have reached this decision on the belief that I can deal with this security risk (if it does not get worse). I know Burkina Faso very well, as I have been there regularly since 2011 and have lived there for over four years. My husband is Burkinabe. I have a lot of contacts and am well connected. This enables me to better assess dangers and problems, but also to be informed quickly.

Figure 2: Training of the proximity police (Policé de proximité) in Bobo-Dioulasso for traditional chiefs, civil societies, vigilant groups, watchmen and arms seller (Copyright: Janneke Tiegna).

During my first field research I met many important and influential people and I was able to build relationships of trust with key figures. The fact that I have been in Burkina Faso for longer periods of time, am married to a Burkinabe and have the nationality opened me doors. With my experience and knowledge, I am not seen as a “white woman from outside”. I hope that I can use this advantage in further researches in Burkina Faso.

Figure 3: Together with the Koglweogo of Siehnon (Karangasso-Vigué) to discuss about their prohibition and the problems with the Dozo (Copyright: Janneke Tiegna).

Written on 05 October 2020

Janneke Tiegna is a research assistant at the University of Leipzig in Germany and pursues her doctorate in the project “Local self-governance for the production of security: vigilant groups in Burkina Faso” within the research group “Local self-regulation in the context of weak statehood between antiquity and modernity” at the University of Würzburg. She has researched about the popular insurrection in Burkina Faso in 2014 and social movements. She worked for the GIZ (Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) in Burkina Faso.

Contact: Janneke.Tiegna[at]uni-wuerzburg.de

Footnotes

[1] Burkina Faso recorded the first cases of the coronavirus on March 9, 2020. On March 21, 2020, a curfew was imposed across the country from 7 p.m. to 5 a.m., the airports and national borders were closed until 1 August 2020. Entry is possible again under special entry conditions. 679 people in Burkina Faso are currently infected with Covid-19 (2123 infected total, 59 dead, 1385 recoveries, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, as of 3 October 2020).

[2] For several years now, the Federal Foreign Office has issued a partial travel warning for Burkina Faso. My research communities Bobo-Dioulasso and Karangasso-Vigué in western Burkina Faso and the capital Ouagadougou have not yet been affected by the travel warnings.

[3] The figures are based on my own statistics on the basis of media reports from over 20 Burkinabe and European online portals. These figures do not demonstrate absoluteness. They must be viewed having in mind that the media cannot report on all Islamist attacks. Furthermore, there may be deviations if the number of people killed increases after the reporting or the number of injuries is not explicitly stated.