Online Breastfeeding and Digital Fieldwork meets Coronavirus

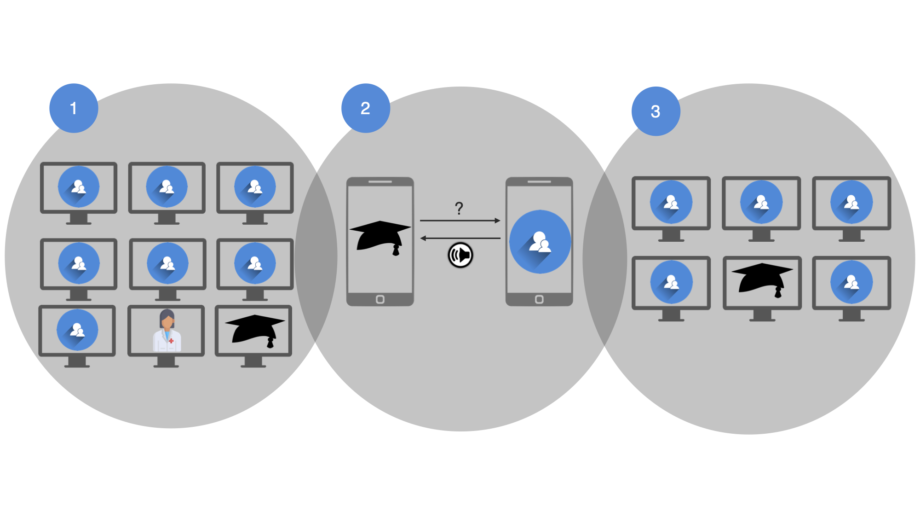

Image 1: Solutions for an online based fieldwork: a well-designed and reflected methodologi-cal mix. Graphic by Ina Tanita Burda.

The maternal breast is often the first place to get food and love for newborn babies. As a first station in the nutritional biography for a lot of people, it is worth asking if there are any normative implications related to. How do one breastfeed in public? Next to the corporal dimension, what else is happening to the mother while breastfeeding? My participant observation in play groups and breastfeeding groups was planned to start in April 2020 with the aim to study breastfeeding as a social practice. But with the beginning lockdown in Germany in the end of March 2020, these plans were invalid as all physical occurring groups were cancelled. The first advices I got when I talked about my collapsing PhD-project were to simply change the whole topic and shift my focus away from the breastfeeding mothers or to say good bye to an ethnographic research. After the first shock, I clearly decided that in any case I wouldn’t do anything else than that, including a participant observation and a well-designed methodological mix. I decided that especially in such times like the actual pandemic, it is even more important to document everyday life which is now shaken to the core. But how would that be possible? How would it work to transfer a research which is based on mutual trust and knowing each other into the internet with participants only known virtually?

Breastfeeding online and offline

Especially when we talk about such an intimate topic like breastfeeding, sore nipples and crying kids I expected to face some challenges. However, when I looked around where and who is dealing with the topic of breastfeeding, I found several promising sources. The international Instagram community is talking about trying to make breastfeeding more visible and respected by the society by using the hashtag #normalizebreastfeeding (around. 1.000.000 posts on Instagram) and also in Germany, there are some blogs which are engaged in that topic. That cited hashtag has no German equivalent which is nearly as relevant with a similar number of posts. There is #stillenistliebe[1] which has only around 47,800 posts. When I first contacted the authors of a blog which has a focus on breastfeeding in public places, I was positively surprised how open the authors were and how friendly they agreed to participate in my research. In a phone call with one of them, I got to know about the midwife who took care of her after the birth of her son. I also contacted that midwife who initiated an online breastfeeding group with the beginning of the pandemic, and I was, again unexpectedly, invited to take place in it. So, I started my online participant observation in the end of May 2020.

But why breastfeeding? A short excursus about the topic: The WHO recommends to breastfeed exclusively for six months and to continue breastfeeding for at least two years. Breastfeeding should happen on demand without any planned times. As my research is situated in Germany, here are some facts about the current breastfeeding situation (based on a pre-published chapter of a long-term study of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung e.V.[2]. Two weeks after the mothers left the hospital with their babies, 71.2% of them breastfed their newborns exclusively. After four month there were still 55.8% of them breastfeeding. Even after one year, 41.1% breastfed their babies at least sometimes. The numbers of the cited study illustrate the relevance of that kind of newborn nutrition in Germany. But the study also found out that at least half of the interviewed mothers were reporting on (mostly initial) breastfeeding problems such as sore nipples, not enough milk, too much milk, babies who are not gaining enough weight, etc.. That makes clear, that mothers who are facing a life changing situation anyways, are also confronted with the corporal experience of giving birth and feeding their newborn babies. When there is no pandemic happening, there are several possibilities to get mentoring in such a situation (in Germany), like in so called breastfeeding groups which are often managed by a midwife or another professional of that field and where is happening a lot of mutual exchange of experiences and advices between the mothers.

Fieldwork online?!

Now that the coronavirus regulates the everyday life and physical contact is reduced to a minimum, these open meetings are not happening anymore. That’s why I had to change my analogue planned fieldwork anyways and decided to put it in the internet. The group I am visiting actually for my participant observation was meant to keep an open room for help and mutual exchange. This group was happening once a week for one hour and since September, it is happening one to two times per month via online video conferences. Some of the women are participating regularly and others take only part if they have a concrete problem. After every woman presents herself and her baby, she has the possibility to report on her problems and the midwife answers. After that, the other women are invited to comment on it and then it’s the next ones turn. Mostly the women don’t talk only about breastfeeding but also about other difficulties they are confronted with such as sleep, first additional meals, crying, milk congestion, etc.. After every woman had the chance to talk about her situation, the midwife leaves the room and the women have the possibility to stay and talk for a while. The women only use that possibility recently and didn’t do it at all in the beginning. They talk about things like nursery schools, clothing, nice places to visit in the pandemic with the baby. During the time when the midwife listens to the women reporting on their problems, everybody who isn’t actually involved in that topic, turns off her microphone. From a methodological point of view, that’s highly problematical in a participant observation where “their minor grunts and groans” as Goffmann calls it (1989: 125) are as important as what the people have to say, but which is not hearable. Another surprising thing is, that the group talks a lot about breastfeeding without having seen one breast in the camera. When the mothers breastfeed, they put the cameras in a way that one could only see the head of the mother or the breasts are covered by a shirt or something similar. So, how such a corporal thing like breastfeeding would be discussable in an online setting?

To hear a bit more of these “grunts and groans” (ibid.), I made some asynchronous audio-interviews with five of the women who participate regularly in the group and two women from the Instagram blog I mentioned before. I sent them one question per week and they answered me within a week with an audio record.

As a last step the participants of the interviews should discuss especially the corporal aspect of breastfeeding together. Therefor I did an online video group discussion. I asked them again what breastfeeding felt and feels like and I was surprised that nearly all of them said that this was the most difficult questions of the five I asked. It was a very lively discussion for about 70 minutes. As they talked a lot about learning to breastfeed, corporal knowledge and natural behavior, I ended with the question if breastfeeding is something natural what just has been unlearned and have to be re-learned again or if it is indeed something what has to be learned before it works out naturally.

Complete methodological mix – and now?

Now I feel like being at a point of having enough empirically collected data to do the next step of analyzing and theorizing. But I still have a lot of concerns. One is about my sample: the participants build a pretty homogenous group and may be that’s problematical. Until now, the project was a mere improvisation and doing what is simply possible to do. Now it has to grow to somewhat I can’t calculate. How do theories of corporal knowledge, corporeity and social practice which were written for analogue situations can be transferred to online settings? What is about privacy concerns? I wanted to act as soon as possible in such a world changing moment and didn’t want to waste time searching for a non-problematic privacy messenger program (which I’m sure doesn’t exist). For sure, I asked all of my participants for agreement and guaranteed anonymization of my collected data. But how do I deal with all that now? Where are the ethical borders? Furthermore, I have difficulties to make clear who could be an interested audience for my research and focus it according to that.

In challenging times with a worldwide pandemic, the academic research and well proved and tested ethnographic methods come to a point of not being enough anymore. And it’s even more complicated to find an appropriate way to deal with such an intimate topic such as breastfeeding.

Written on 4 October 2020

Ina Tanita Burda works on her PhD project about Breastfeeding in the internet in times of Coronavirus in a BMBF funded project on Food Cultures at the University of Koblenz-Landau, Campus Koblenz where she also did her M.A. in Cultural Studies. She is interested in the fields of cultural studies, gender studies, digital ethnography and internet-based research.

Contact: izeien[at]uni-koblenz.de

Footnotes

[1] #breastfeedingislove (translation by the author)

[2] German Association for Nutrition (translation by the author)

References

Goffman, Erving. 1989. On Fieldwork. In: Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 18 (2), 123-132.

Mathilde Kersting et al.. 2020. Studie zur Erhebung von Daten zum Stillen und zur Säuglingsernährung in Deutschland – SuSe II. Vorveröffentlichung Kapitel 3. https://www.dge.de/fileadmin/public/doc/ws/dgeeb/14-dge-eb/14-DGE-EB-Vorveroeffentlichung-Kapitel3.pdf. Last access: 04/10/2020.

WHO. 2020. Breastfeeding. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2. Last access: 04/10/2020.