Geertz in the Background

A Thick Description of Online Activism

Consider a space of rectangular shape. In which a small world is contained. The bust of a figure can be seen, contracting the eyelids of their right eye, once, twice, and waving. Next to this world, you emerge, existing in moment you can touch, and the air you can breathe, but catapulted into a similar space in two dimensions, rectangular and showing only your immediate surroundings. You look to your left, and another emerges, a world of its own confined in yet another rectangle, with its own individual, and for all practical purposes its own universal laws. These worlds and spaces coexist in a specific time and coded space of encounter. They can speak, to themselves, and to each other. They can disappear from sight, they can disappear from sound, they can disappear altogether, rejoin, or be banned depending on who the space of the encounter belongs to. These adjoining worlds share purpose and friendship, feelings, and commitment. These adjoining worlds as I know them and live them on my computer, shape the Fridays for Future movement in Mexico in times of pandemic.

A connection is being established.

I cannot recall how often I have read these words in the past months. The exercise of establishing a connection and then finding myself face to face, with myself. The odd exercise of being able to see every movement of my own face, a mirror, at times welcome, at times a mocking experience. I wait for someone to connect. I receive a text. “Not going to make it, can we reschedule?” I look at myself one last time and close the window leaving SSL port 443.

A connection is being established.

For the past seven months I have been engaging in iterative bursts of digital ethnography. Getting to know individuals involved in the Fridays for Future environmental movement in Mexico. When I began this work, I wanted to know what role digital media played in mediating, reimagining and redefining environmental understandings and realities in this community. As of now I can say a more important one than before.

I wanted to emerge myself in these individuals’ entanglements with and understandings of science and truth.

“What future do you see?”, I ask. “It wasn’t this one.” They say.

“What future do you fight for?”, I ask. “Now that’s a different question.” They say.

Because of the nature of the movement I had always planned on including digital ethnographic methods as a central component of my fieldwork. However, the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was a future I failed to imagine. The prominent role these methods would play in my fieldwork has come as a surprise.

A connection is being established.

I find myself toeing the border of a screen to Tuxtla Gutierrez in the southern state of Chiapas. A young kitten stares at me from across the screen as I greet her caretaker. He quickly contracts the eyelids of his right eye. He hasn’t seen many people during the past couple of months, the pandemic is raging in Mexico with deaths in the thousands. We go over time; I hurry to hang up.

A connection is being established.

I cross the vastness of the ocean one more, traveling through time. When I open my eyes, I see her. I stare across the screen and see the sun pushing its way through the window in her bedroom. Outside my own window I see only darkness, the flickering streetlight reminding me its past midnight. I point this out and she turns her face towards her window, contracting the eyelids of her right eye. Most of my conversations happen one on one. The process of building relationships something that is left to connecting between two screens, not more.

A connection is being established.

When various worlds line up next to each other, most people choose to not show their small universe. The cameras stay off and it is only through audio and text that they connect. A few choose to reveal their settings, especially if they play a role in moderating, if they have power over the space of encounter. Most however, are but a darkened square with their screenname is bold white text. I do not know if anyone’s eyelids are contracting.

A connection is being established.

The laundry on his bed, the voices coming in from the rooms I imagine surround his.

She is searching for a charger, while her younger sister makes faces at the camera.

His insomnia extends our conversation, I drink coffee in the morning while he is the one staying up. Her parents look over their shoulders, sneaking peaks at the screen.

His family stands in the kitchen making quesadillas.

She leaves the room to sit on the steps which lead to the patio. Looking for a silent space. Looking to connect, amidst the togetherness in isolation.

The eyelids in their right eyes contract.

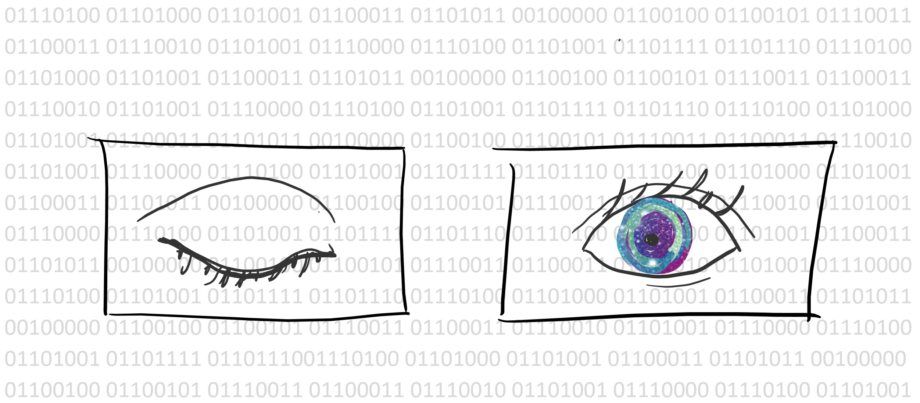

Thick Description in Binary- Illustration by Mariana Arjona Soberon. A background full of binary code, the code spells out “thick description” over and over. In the forefront two rectangles can be seen, one features an open eye and the other a closed eye.

The moderator has ended the meeting.

I look at my notes and hear Geertz in the background. Culture is context. He continues and says:

“Consider … two boys rapidly contracting the eyelids of their right eyes. In one, this is an involuntary twitch; in the other, a conspiratorial signal to a friend. The two movements are, as movements, identical; from an l-am-a-camera, “phenomenalistic” observation of them alone, one could not tell which was twitch and which was wink, or indeed whether both or either was twitch or wink. Yet the difference, however unphotographable, between a twitch and a wink is vast; as anyone unfortunate enough to have had the first taken for the second knows…” (Geertz, 1973)

Is it a twitch or a wink? This question and others of its kinds circle my mind. The context slips through my fingers since the one seeing the contracting eyelids is just me. I find myself struggling to find footing on the thick description where context and interactions play an indispensable role. Context slips when these adjacent worlds come so near and yet fail to touch. Perhaps I need to rethink context.

Written on 5 October 2020, revised on 11 October 2020

Mariana Arjona Soberón studied sociocultural anthropology at Yale University in the USA, followed by an interdisciplinary master’s degree in environmental sciences at the University of Cologne. She was born and raised in Mexico and has been touring the world through academia. She is currently a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology and the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society at the LMU in Munich. Her research focus lies on the interactions between digital media, environmental understandings, futures, science, and activism. The working title of her dissertation is “#ViralEnvironmentalism—Digital Landscapes of Environmental Activism, Fridays for Future and Beyond.” Mariana is the academic manager of the International Master of Environmental Sciences at the University of Cologne where she also lectures on Environmental Communication and Narrative.

Contact: m.arjona-soberon[at]ethnologie.lmu.de

References