Doing Good/Doing Right and the Limits of Negotiation

Preface: Why the interest in the “limits of negotiation”?

Katja Rieck, Orient-Institut Istanbul

Before delving into the main part of this blog post, it is important to begin with a few remarks on the significance of the topic of this blog series, which may not be clear to those who have not studied anthropology. During our discipline’s early years, up until the 1980s, our main aim was to document and analyze the diversity of human cultures around the globe. To do this, we were expected to go live somewhere far away, learn the local language, and learn all about the culture of the people we were living with. After a year, or perhaps two, we should return and write some articles and a book about it, providing some sort of holistic documentation of various aspects of the culture we had encountered.

However, this task, straightforward as it might sound, was anything but. Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, the idea of culture as a container of coherent ideas shared by a society in its entirety was already being called into question. Women anthropologists, for example, would get very different perspectives on the societies they studied than their male professional counterparts. And in the politically charged climate of those decades, many of the upcoming anthropologists at the time were especially attuned to how the societies they studied were marked by internal differences based on distinctions made according to sex/gender, age, economic inequality, family membership, religion, and so on. These internal differences impacted how a particular member of society viewed and experienced her culture. This scientific attention to the internal diversity of cultures as well as their contradictoriness changed anthropologists’ conception of culture as an object of study. So, for many decades now, we have been studying societies and their cultures as internally heterogeneous and marked by differing and even contradictory understandings of how life in this society works or ought to work. The socio-cultural “order” that we, as anthropologists, try to document is therefore fragmented, contradictory and the result of conflict and negotiation between its members. Consequently, it became our primary task to document this in our accounts (sometimes making them very difficult reading). We therefore focused our studies of social life as a fragmented plurality of fields, “discourses” or “language games” that took shape as a result of actors’ tactics or strategies, a physics of social forces leveraged through negotiation. This was pretty interesting stuff and allowed us to produce work that documented socio-cultural worlds in a nuanced and complex way.

However, this said, some readers may point out that not ALL of socio-cultural life is malleable. There are moments of hardening, rigidity and closure, when societies and their members no longer negotiate. Now, we often see this at moments when persons or groups insist that a particular way of doing something is the RIGHT way or the GOOD way. At these times, conflicts become framed not in terms of differing interests or perspectives that must somehow be harmonized, but as moral or ethical issues that pit good against evil or right against wrong. The integrity or even survival of the group is ultimately what is at stake. And because giving way to find some middle ground entails deviating from what is good/right (and so drifting towards the wrong or the bad/evil), there is no willingness to negotiate. It is at these moments that societies present themselves at their most inspiring, but also at their most terrifying, as one person’s paradise can be another’s damnation.

To see what I mean, we can look at examples from current events that many of us are familiar with. Greta Thunberg, for example, has inspired many around the world with her steadfast and forceful insistence that climate change is an existential crisis that must be stopped immediately:

People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction. And all you can talk about is money and fairytales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

(Speech at the UN General Assembly, text reproduced by The Guardian, 23. September 2019)

We can see here, how Greta Thunberg reframes the issue of climate change. Conventionally it was treated as a technocratic problem with economic and humanitarian consequences. Policymakers have negotiated target values for CO2 emissions, balancing the interests of economic growth with the suggested values forecasted by scientific models. The short quotation from her speech at the UN General Assembly on 23. September 2019 shows how Greta redefines the problem as an existential crisis costing not only human lives, but initiating an era of “mass extinction”. Her angry “How dare you!” makes it clear that, in her view and the view of all those for whom she speaks, world leaders and policymakers have violated a moral boundary and committed a betrayal vis-à-vis younger generations and others who depend on the integrity of the planet for their continued existence. Her words make clear: the time for negotiation and compromise has ended.

At the same time, such steadfastness and moral conviction can engender violence and terror. History and current events have many examples of how morally inspired projects can entail bloody consequences. In the United States, the Army of God (AOG) has since its establishment in 1982 been responsible for numerous murders, attempted murders, and clinic bombings in its efforts to prevent abortions (or in their view, to prevent the murder of innocent babies) (https://www.armyofgod.com/). And in West Germany, between 1970, the year of the group’s founding, and 1998, when it announced its dissolution, the Red Army Faction (RAF) executed numerous bombings, kidnappings/hostage takings, and a hijacking in their efforts to carry forward what they saw as the denazification of Germany and to stop what they referred to as US imperialism. Their struggle against “evil” was manifest as terror to those German citizens who were not committed leftists. Readers can no doubt think of plenty of other examples from more recent events. In any case, it is quite clear that these moments of non-negotiability when actors will take great risks upon themselves, even sacrificing their own lives and those of others rather than giving way to compromise, are just as important a part of our socio-cultural realities as the intricacies of negotiation that we have spent so many decades studying.

Ethnography of morality and ethics and the limits of negotiations?

So, what can the anthropology of morality and ethics contribute to our understanding of situations and contexts set as apparently non-negotiable? Situations where we are dealing with idealism, altruism, care, conviction, righteousness? In the following “vignettes”, my colleagues Philipp Zehmisch and Christos Panagiotopoulos share some thoughts that have been provoked by their field research. Academic conferences are places to discuss works in progress and to explore ideas. By sharing our ethnographies at these events we often open novel perspectives on the topic at hand. So what follows is a glimpse of our work and analyses in progress, fragmented, emergent, but maybe thought-provoking or at least interesting. We share our work also to give those outside the anthropological community a glimpse of how discussions of a topic grounded in ethnography can lead to unexpected insights.

Progressive activism in Pakistan and the limits of doing good

Philipp Zehmisch, Lahore University of Management Sciences

In recent years, I have been engaged with progressive activism in Pakistan, which has provoked me to think about how activists negotiate their own limits of doing good. In Pakistan, the figure of the progressive encompasses a wide spectrum of persons in opposition to the national mainstream – from leftists to liberals, artists to academics, and ethno-nationalists to “anti-nationals”. A common denominator is their ethical stance: progressives perceive the social and political situation in Pakistan as “oppressive” and morally “corrupt”, if not “evil” and “perverse”. They clearly hold the “Establishment” – bureaucrats, the military, corporates, feudals, and religious elites – responsible for a variety of problems that plague the Pakistani society as a whole: ranging from brain and wealth drain to the sell-out of infrastructure; from toxic air to water pollution, salination, deforestation, and the increase of extreme weather phenomena; from rampant poverty to defunct public and educational services to various forms of everyday violence; from gender, racial, and caste discrimination to religious bigotry and chauvinism. Thus, doing good means seeking to change the status quo by somehow challenging these “evils” through activism.

Exploring the point of view of activists, I have started to reflect on what it means to cling to an ethics of doing good in the light of various forms of state repression.

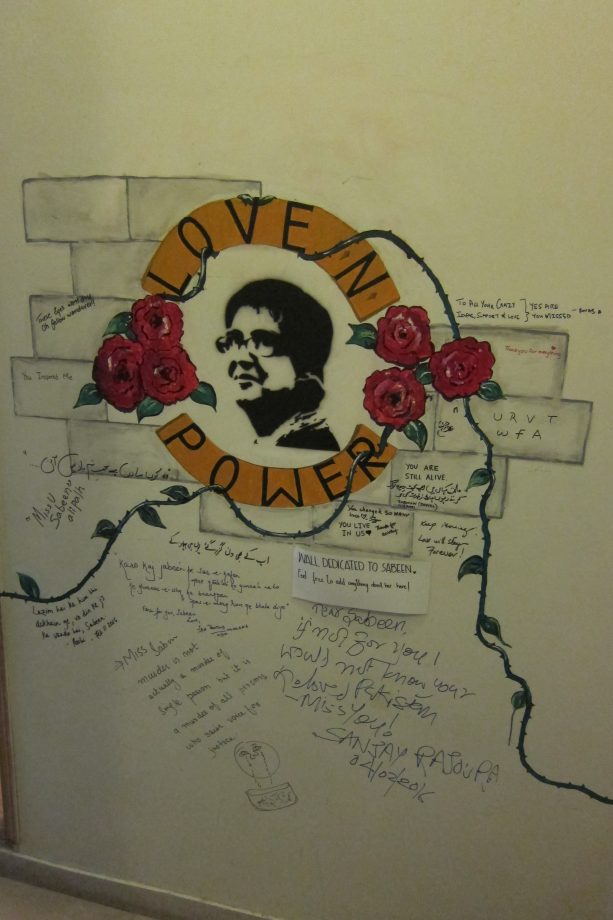

Mural depicting Sabeen Mahmud, one of the many who

paid for their moral engagement with their lives,

(photo by Philipp Zehmisch)

What are the personal, material, or psychological limits of progressive activists’ engagement? I would suggest that progressive activism as an ethical stance implies risking one’s own status and potentially one’s own health or even bodily integrity. Activists are routinely subjected to state surveillance and intimidation. Furthermore, many face the potential dangers of victimization by online trolling, enforced disappearances, torture, and target killings staged as “police encounters.” Hence, while most progressives are conscious and clear about their limits of negotiation – the ongoing political and social crisis of the country – they also constantly negotiate the limits of their own activism. Activists therefore live in a constant state of tension, navigating between the principled, non-negotiability of their ethical engagement for a better Pakistan and the fear for their personal and bodily integrity. At the same time, one might ask: How does the existential threat to their being that their activism provokes add to the moral gravity of what they are fighting for? If Greta Thunberg’s insistence that climate change is an existential threat has reframed climate change as a moral, rather than technocratic problem, then does the same hold true for the cause of Pakistani progressives? In other words, does the existential threat of involuntary disappearance or death lend moral force to the progressive cause?

This notwithstanding, I have observed that for activists to continue both their everyday lives, as well as their activism many must suppress their personal fears of being harmed. But the limits of activism can also be stretched in various other ways. If activists belong to more elite social classes, for example, they may be able to risk more – ironically, precisely because of their personal and family connections to parts of the Establishment against which they are taking an ethical stance. On the other side of the equation, we find that those who have no links to the Establishment are left to the mercy of those who wield power to mete out their fate. Social media, however, may provide some protection, albeit largely for those with elite connections. Activist bloggers who suddenly disappeared, for example, have been subsequently freed after months of uproar from online communities who called for their release. In another case, a powerful social media campaign protesting the horrific and systematic sexual harassment of students at a local university led to the resignation of the vice-chancellor. I would therefore suggest that the powerful tool of social media has expanded the negotiating limits of those doing good. Not only does social media provide (potentially global) networks of solidarity, as was evident in the case of the bloggers, by expanding the scope of the public sphere; it also increases the pressure of accountability, allowing the enforcement of what is right (legally) and/or licit (morally) by public tribunal. Knowing they have a supportive public behind them, activists are supported in maintaining the non-negotiability of their ethical stance. My observations of Pakistani progressive activism therefore suggest taking a closer look at the role of social media and how it impacts upon the agency of these activists. A next step would be to see how these observations relate to existing studies of social media’s impacts on activism for socio-political change and whether the specificity of the situation in Pakistan can shed new insights in this regard.

Creative non-negotiability: the ethics of juvenile delinquency rehabilitation in France

Christos Panagiotopoulos, Cornell University

Through my ethnography I wonder: How are juvenile rehabilitation institutions dealing with difficult cases of juvenile delinquency? How do they negotiate the balance between containment and rehabilitation, imprisonment, and education? And what happens when the so-qualified ‘difficult adolescents’ jeopardize traditional institutional strategies for rehabilitation? In France, professionals working in the juvenile judicial services, invested in the rehabilitation of adjudicated, criminal, radicalized or errant youth are sometimes confronted with particularly challenging cases. In these instances, specialized educators, social workers, or other judicial personnel often turn to psychiatry for simple, effective and immediate solutions. When confronted with particularly violent and agitated adolescents’ professionals, in their attempt to rationalize these situations, are implicitly medicalizing deviance. They, therefore, find themselves asking child and adolescent psychiatrists to treat adjudicated adolescents, even in cases when the adolescents don’t suffer from mental health issues, or aren’t diagnosed with any mental illness. Of course, such cases are permeated by culturally informed representations of ‘madness’, themselves linked to symbolically and historically charged visions of alterities in France, making this negotiation part of a broader silenced dialogue on race and ethnicity in France.

When non-mental health professionals, such as specialized educators, decide that an adolescent is crazy, or that they suffer from a mental health issues, thus making them incapable of partaking in the rehabilitative and educative processes that institutions have predefined, then they attempt to approach a mental health professional, usually a psychiatrist, who validating their hypothesis, would offer a solution to their problem. The psychiatrist is thus often represented as someone holding the ‘magic pill’ and who can offer efficient solutions in dealing with adjudicated adolescents not falling into familiar patterns. So, pedopsychiatrists working closely with judicial institutions are currently over-solicited with demands for medicalizing juvenile delinquency – which they are mostly suspicious about. This negotiation of juvenile delinquency often brings psychiatrists to explain their work and justify why they are refusing to pathologize what they perceive as social, familial, or other structural violences that the adjudicated adolescents have been, or are, experiencing and that are actually the underlying context of their problematic behavior.

This negotiation often ends when judicial personnel, such as specialized educators, or caseworkers, hold meetings with mental health professionals, especially psychiatrists, to discuss a particular case study. In this interaction of professional fields, psychiatry’s omnipotence, invested with all the projections and high expectations of non-psychiatrists, is shattered by the mere discourse of psychiatrists. I vividly remember in such a meeting, of a young agitated psychiatrist emphatically asking his colleagues to “stop asking him to medicalize juvenile delinquency”. The psychiatric expertise rejoices of such authority in this context, that makes it impossible for the other interlocutors to ignore the plea.

Through this schematized process, the medicalization (or psychiatrization) of juvenile delinquency becomes non-negotiable. The authoritative presence of a psychiatrist in a team meeting, and their explicit unwillingness to medicalize difficult adjudicated youth just because they are too problematic for local teams to deal with, creates a zone of non-negotiability. A non-negotiability, that instead of shattering individual agency, allows professionals to think about their own responsibility vis-à-vis an adolescent. Instead of externalizing responsibility to the hands of an all-mighty psychiatrist, it invites specialized educators to find novel efficient ways to engage difficult adolescents. The psychiatrist by ending negotiations – through a commonly acknowledged authority of expertise – opens up a space of creativity, where specialized educators can think about alternative ways in approaching distant, difficult or over-agitated youth. But also, besides the day-to-day pragmatics of rehabilitating juvenile delinquents, this non-negotiability opens up a theoretical space for thinking about juvenile delinquency differently in approaching it, not through the lens of an individual-centered psychopathological reading, but through an engaged, inclusive, socially, and culturally-sensitive rehabilitation strategy, while forcing social actors to ask themselves : what is my responsibility in the social integration and care of this anomic youth?

Some final remarks

Katja Rieck, Orient-Institut Istanbul

So, to return to the question: What can the anthropological study of morality and ethics in concrete situations contribute to our understanding of situations and contexts set as apparently non-negotiable, situations where we are dealing with idealism, altruism, care, conviction, righteousness? For one, as Christos has observed in the interactions between psychiatrists and other specialists intervening in the problem of juvenile delinquency, is that this moment of non-negotiability, far from being a point of closure, as I assumed at the outset of this post, we can see it as opening a new space of creative possibilities. There is a colloquial saying: When one door closes, another one opens. Non-negotiability seems to be the means by which other doors are pried open; it forces actors to find or create new courses of action. In contexts where moral issues are at stake, issues of right/wrong or good/evil, the work of activists (such as those that Philipp has engaged with) is often to shake up the status quo, to communicate that the present situation cannot continue. In contexts where the “evil doer” is the “Establishment” that is backed by the force of state, two parties stand in a face-off of non-negotiability. The role of a wider public acting as a kind of collective ethical conscience and of networks of solidarity made possible by social media can potentially tip the scales in favor of activists or establishment, depending on where solidarities are placed. In any event, we should look more closely at non-negotiability as something socially productive. Just as in speech we know that silence is also part of communication, there is non-negotiability in social action. But how and when does it work? Are there different practices, tactics or strategies of non-negotiability? Do these further differ by socio-cultural background, class, ethnic belonging, etc.? How is non-negotiability impacted by gendered positions? Because moments of non-negotiability are so prominent in social situations where moral/ethical matters are at stake, the anthropology of morality and ethics might be particularly well suited to provide empirically grounded insights on these questions.

About the Authors

Katja Rieck is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Orient-Institut Istanbul (Turkey), where she is developing a collaborative research project with her Iranian colleagues on civil society charity organizations in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Her work focusses on the interrelationship between (alternative) economic practices, ethics and morality and processes of socio-political transformation. Her monograph “A Matter of Principle: Political Economy and the Making of Postcolonial Modernity in India, a Foucauldian Approach”, which is based on her dissertation research, will be published in 2020 by Nomos. e-mail: k.rieck74@gmail.com

Philipp Zehmisch is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the Lahore University of Management Sciences. His research combines Political Anthropology, Subaltern, Borderland, and Migration Studies with an investigation of how ethics affects contemporary legacies of India’s partition. Philipp’s award-winning dissertation “Mini-India: The Politics of Migration and Subalternity in the Andaman Islands” was published in 2017 with Oxford University Press. e-mail: Philipp.Zehmisch@ethnologie.lmu.de

Christos Panagiotopoulos is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at Cornell University (NY, USA) and an invited French Government Scholar at EHESS (Paris, France). He works at the intersections of psychological anthropology, the anthropology of ethics and morality, and the anthropology of religion. Currently he is conducting an ethnographic study of experimental juvenile rehabilitation in France, researching the negotiation of medical, psychological and educational approaches to rehabilitation within a secular institutional culture. email: cp582@cornell.edu