Shared Isolation and Digital Connectedness in the United States

Viewing the World Through My Timeline

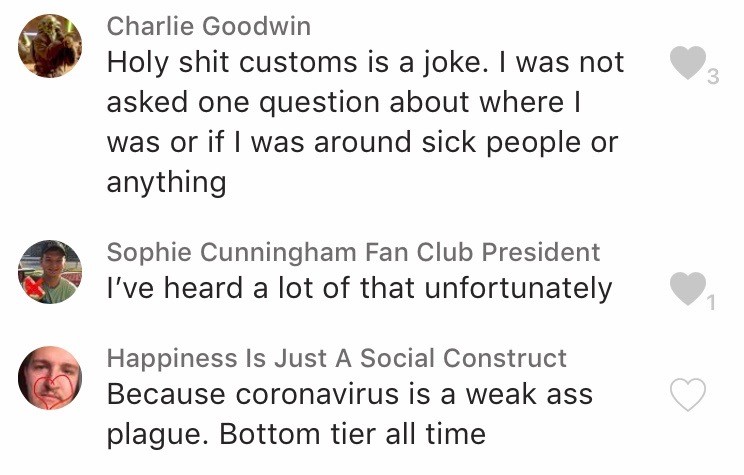

On Sunday, 8 March 2020, I scrolled past the following exchange in the “Dixie Chicks Fan Club,” (the name of the group has since changed), a GroupMe group containing 21 students and alumni from the same sports radio club at the University of Michigan.

Image 1: GroupMe Screenshot, Copyright: Morris Fabbri, Reproduced with permission of the visible group members

Like most millennials, Jason and I are active on social media. Twitter is my opiate of choice. I first joined the platform in 2009. I appreciated Twitter for its openness: with a 140-character message and a click, I could interact directly with friends, comedians, celebrities, or anyone with a public account. I gravitated toward the site to sate a voracious appetite for sports media: the stream-of-consciousness nature of the platform made Twitter a place where I could share a single basketball game with scores of witty, insightful people who loved the game like I did. Over time, as people formed inside jokes through repeated viewings and tweeted about their lives and interests outside the confines of primetime sporting events, the people on Basketball Twitter became familiar with each other. As my own interests expanded beyond sports, I followed new accounts and participated in that same iterative process of belonging in other spheres. But while I have come to know the people who comprise my timeline through observation, most of them have no idea who I am.

As I learned to parse through the rapid-fire overlap of information, Twitter became the hub for my view of the rest of the world. Every day, for hours, I absorb overlapping streams of consciousness from sportswriters, journalists, comedians, left-wing political commentators, academics and, more recently, infectious disease and public health experts. Jason and I aggregate our information in similar ways, but while he downplayed its severity, I knew COVID-19 was a serious threat. To better understand a disconnect in how we perceived the same facts, in the space that follows, I will probe how social media spreads information in a pandemic. Within our present pandemic and in the pandemics to come, communication shifts from shared physical spaces to digital platforms. Through my own Twitter timeline, I will highlight compact and powerful messages of dissent, unity and narrowly tailored support that show the potential of these platforms. By reflecting on my interactions with people who get their information elsewhere, I will explore perspectives left out of digital discourse. As a polarized and fragmented internet fills the social void created by physical distancing, I hope that by describing specific forms of connection and alienation, someone smarter than me can expand access to the riches of social media while shielding newcomers from the bile that lurks around every corner.

My Timeline On COVID-19

For weeks, the topic of coronavirus has overwhelmed my timeline. As of 17 March, every state in the U.S. has recorded a case of coronavirus within its borders. As state and local governments shut down their economies to avoid disease spread, people look for explanations. The website of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers guidance for individuals and businesses to protect themselves. In walls of text, readers are told to “plan” and “be ready” with little insight into how drastically COVID-19 and the government’s response will affect their daily lives. As the New York Times reported on 15 March, social media fills this void with sound and color. On Twitter, scientists can push back on misinformation as soon as it is generated. Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at center of the Washington outbreak, has seen his follower count explode from around 10,000 to, at the time of writing, almost 120,000. Bedford is part of a community of doctors, Ph.Ds, public health experts and science journalists whose platforms have ballooned because they can respond directly to popular confusion, providing unfiltered insight in plain language. Economists, historians, and other experts also contribute to coronavirus commentary. When they harmonize, Twitter juxtaposes microscopic evidence with historical and social context to set accurate expectations for our present and future pandemic lives. In reality, my timeline often looks like differently credentialed people jockeying for greater authority to describe a shifting reality. I like to think that both the harmony and the headache-inducing squabbling and uncertainty help me understand the effects of a vast and complex problem.

In addition to breaking news, Twitter can offer solace and solidarity: videos of Italian balcony chorales, virtually recorded Dutch symphonies, and new games invented by homebound Chinese people went viral because they echo a universal pursuit of joy and transcendent collaboration that continues after the world is torn apart. Images of monkeys warring in vacant Thai streets proliferate alongside gallows humor and wordplay that make light of our newfound proximity to death: when we become familiar with the absurd and the unknown, maybe it will all be less daunting. I’ve seen scores of people tweet that they can no longer travel home to care for ill and elderly family for fear of spreading disease. The pandemic brings tragic trade-offs: when broadcast with a general audience, they join a consensus of virtuous and collective sacrifice. Finally, Twitter can also remind us that these strange new times aren’t so strange or new: disabled persons, people with chronic illnesses, and others who face barriers to the security and sociality many take for granted can share advice and solicit empathy for a lived experience of isolation now shared with most of the world. My exposure to these messages is fleeting and partial; each provides an opportunity to share someone else’s struggle, whether through shared literature or an opportunity for dialogue. Presented in a steady stream on my phone screen, however, most provoke indistinguishable sparks of muted empathy—the best tweets will end up as something I reference in passing on a video call with my real friends.

COVID-19 Seems Abstract and Remote to People Who Aren’t Paying Attention

The observed consequences of this new plague are breathtaking. Within a month of the first case in Italy, 60 million Italians can no longer leave their homes without permission. Doctors are considering age limits for access to intensive care. Funerals have been banned; according the editor of a local paper, “people die alone and are buried alone.” At the time Jason sent his message, the coronavirus had already paralyzed China and devastated Italy. Yet Jason, along with millions of other Americans, seemed to have no grasp of how bad things will get when people help spread a plague.

On 16 March, I went to my local Harris Teeter to restock my nonperishable foods. I stopped to take a picture of an empty aisle where shelves once held bottled water and toilet paper. An older woman asked why I was taking a picture of the aisle; I replied, “Because it’s bizarre.” She then launched into a rant, telling me I need to get “prayed up,” ridiculing people packing their shopping carts to the brim, noting that she is on a fixed income and thus could not fill up her cart even if she wanted to, and asserting that because she had worked in cleaning at Duke for 26 years, she knew what was up. As she spoke, two East Asian women wearing face masks turned down the aisle next to us. My new mentor injected “you know, we got it from them” fluidly into her speech. I’m not really sure how all the components of her speech fit together. I only remember snippets. I don’t know what I would have said if she gave me space to respond (other than maybe “hey, don’t be racist!). As an older black woman on a fixed income, she is more likely than me to suffer from this pandemic. If I showed her the same tweets that sensitized me to the threat of the coronavirus and the damage caused by anti-Asian xenophobia, I don’t think they would resonate in the same way. I don’t follow anyone like her on Twitter, either: the academics and advocates who write about her life on my timeline are a far cry from representation. Furthermore, I wouldn’t blame her for dismissing a strange man who demanded she add existential fear to her more concrete and pressing concerns.

Image 2: Image of grocery store aisle, Copyright: Morris Fabbri

On 17 March, my brother Tony sent me a Snapchat image of his new patchwork beard-and-goatee monstrosity. In addition to communication with his friends and girlfriend, Tony also gets a lot of his news from Snapchat’s “Discover” page. He has decided to experiment with his facial hair because my parents will not let him go to work at the Little Caesar’s pizza store where he is an assistant manager. Tony lives at home. He enjoys the income and the responsibility that comes with his job, so he resents being kept at home. I told him my parents gave him good advice because they might die if they catch this virus. He countered that Mom and Dad aren’t that old, and neither of them have compromised immune systems or chronic respiratory conditions. My parents are in their 60s; both smoked cigarettes for decades before they quit. I insisted that even relatively healthy baby boomers can die from this virus. He replied “Ok.” I feel a responsibility to correct Tony and Jason’s underestimations, but I understand where they are coming from. In our short and sheltered lives, apocalypse tends to happen at a distance, viewed through headlines that rarely bear on our daily lives. We scrutinize the details out of academic interest, not practical concern.

On 18 March, a news bulletin crossed my timeline. “Italy reports 475 new deaths, highest one-day toll of any nation.” The doctors and public health academics tell me we are about ten days behind Italy. My mom started an e-mail thread to check in with family members around the country. One is a hospitalist in Washington. His wife, who is in her 60s, writes that they are already triaging ventilators. If she fell deathly ill, she would be deemed too young to access one. I saw this e-mail thread after a round of disc golf at a local park in Durham, North Carolina. It was 80 degrees and sunny. The park was packed with people throwing discs and families enjoying the weather. No one was coughing. No one wore a mask.

I Wish I Could Explain How COVID-19 Became “Real” To Me

My friends and I are social distancing now. They’ve taken cues from their social circles or their jobs; maybe they were persuaded by something they read online. Twitter can be a generative force: media goes viral through retweets by its consumers, signaling that the message within is important. The brevity required by Twitter’s character limit makes Tweets a perfect package for headlines, and users flock to Twitter expecting to read, share and react to breaking news. Journalists overwhelmingly list Twitter as their favored social media platform, and their stories fill magazines and newspapers, serving as fodder for news and talk shows. Over time, these messages diffuse to the general public, where they are again measured against real life. Somewhere in this process of consensus formation, coronavirus becomes real enough to motivate action.

I reflect on my observations of Jason, Tony, the woman at Harris Teeter, and others’ perceptions of COVID-19 because I have a limited understanding of how they build their world views. I can grasp at what I know about their lives and their backgrounds; I can describe exposures we might have in common, but I cannot describe the parts of their lives I cannot see. I know that thanks to some combination of education and comfort with social media, I can access and interpret all the tables and graphs that have become the lingua franca. I understand what it means to #FlattenTheCurve. Perhaps because I’ve spent a decade on Twitter, I’m accustomed to connecting and extrapolating from fragmented bits of data. When there were about 8 confirmed cases in North Carolina, I cancelled a flight home to see my family for the first time in months. In that sense, my Twitter feed has “worked” for me in that it has allowed me to protect myself and my family from infection. If I could describe precisely how and why it works for me, I could recommend ways to make it work for other people. But in reconstructing my own epistemology through personal reflection, I can only gesture at moments in an understudied, chaotic process. I reflect on Twitter because it’s what I know, but for all the sound and color social media has to offer, the pandemic still feels surreal.

The gospel of social distancing has been slow to take hold in the United States. I think this is because many people are reluctant to suddenly cease their daily lives in response to an unseen threat. No one who boasts about eating at crowded Red Robins, licks subway poles, or parties at beaches understands what it means to live through a pandemic. We have no frame of reference. Those of us who heed public health advice and distance ourselves do so because we trust the people who tell us that this virus can spread among people who are asymptomatic; that the difference between a 3% death rate from COVID-19 and a 0.1% death rate from the flu means that we might condemn our grandparents to death by visiting them in the nursing home; that the world as we know it is ending, and the only thing we can do to make things less bad is to stay home. And after we accept this reality, we have to get everyone else on the same page.

Social Media Can Be A Gateway To Meaningful Dialogue, But Meaningful Dialogue Usually Takes Place Offline

While Twitter can be a hub for messages that resonate, these can get drowned out in a sea of opinions. As a Twitter expert who dabbles in infectious disease, I wanted to advise people trying to navigate the so-called “infodemic,” a term the World Health Organization uses to refer to “fake news that spreads faster and more easily than this virus.” I called Adia Benton, a cultural anthropologist who is an associate professor at Northwestern University and a former colleague of my boss. Benton is active on Twitter—in fact, she fired off a tweet in the middle of our conversation. During our call, her two small children interrupted to request cookie butter, restroom assistance and maternal love. With Chicago Public Schools closed for the foreseeable future—“ a lot more people are interested in school closures than I ever thought, despite the fact that it’s not what was driving transmission in China, Italy or South Korea”—Benton will juggle increased maternal responsibilities along with her professional life.

When I asked her if anything alarmed her about trends in epidemic coverage on social media, Dr. Benton cautioned against an emphasis on social distancing to the exclusion of other concerns. According to Benton, instead of thinking in “punitive, carceral, legal logics” focused on limiting liability and avoiding social pressure, we should think of “the best way that we can provide care for people—be in solidarity with people around their struggles that exceed COVID—not everyone is walking through the streets thinking about this disease. But it’s fully distorting everyday life for a lot of people who can’t afford for it to be distorted. You can’t pay rent? You can’t buy food? There are a lot of forms of care and solidarity that precede the decision to distance.”

While the coronavirus does not infect along socioeconomic lines, decisions to shut down state and local economies will disproportionately harm the most vulnerable among us. People are justified in their reluctance to accept the conclusions of a conversation that doesn’t ask for their input, in a country where the steady march of progress is accompanied by rampant inequality that leaves so many behind. Anyone with a phone and an Internet connection can make a Twitter account, but without the credentials and connections that attract a following, Twitter is just another place to not be heard.

I have a Republican friend in that student radio GroupMe. He’s on Twitter too, though he follows more right-wing personalities than I. He got laid off from his job on 20 March. The end of his most recent message to us reads: “But this virus is fucking way more people financially than it ever will medically so hopefully the quarantine is worth it.” I’m connected to him through our shared love of Michigan athletics—in another group chat centered around Michigan’s softball team, I pushed back on his suggestion that “if people reported the flu like coronavirus, no one would ever leave their houses.” Through the broadcasts and podcasts we’ve done together, I know my friend as a funny, caring and hard-working man who doesn’t want to kill his grandmother.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) cancelled all its spring sports seasons. The National Basketball Association (NBA) and National Hockey League (NHL) have postponed their seasons too. To achieve an appropriate level of social distance, we retreat from our shared physical spaces. In doing so, we lose most of our traditional platforms for dialogue. As much as I feel I learn from Twitter, my world view isn’t shaped there. I’ve been more informed and challenged by conversations that started in a classroom, moved to a bar and then ended at 2am on a friend’s porch. I got to know co-workers outside my social circles by shooting the shit at the end of a closing shift at Panera, a bakery and café chain where I cashiered in college. For most of our time on Earth, humans have transmitted information via word of mouth in social contexts that allow us to express fully formed thoughts. We connect through tone, touch, facial expressions and body language. We know each other as three-dimensional beings with most of the same wants and needs. Twitter is a stream of disconnected bits of information packaged in 280-character bursts. When I hear divergent viewpoints in person, I can infer from a person’s body language and tone whether they are earnestly expressed; in the same physical space, it’s easy to start a mutually beneficial dialogue. When I see an anonymous account tweet “just wash your hands and you’ll be fine,” I assume it comes from a place of ignorance and malice and keep scrolling. Social media encourages these kinds of shortcuts: refresh your webpage, and uncomfortable interactions get washed away by a new stream of posts. It is easy to feel like part of a movement when all that requires is a public show of assent. The work of building meaningful and inclusive consensus, of addressing the complex social problems Dr. Benton raises, requires a depth of engagement and collaboration incompatible with platforms designed to deliver superficial bursts of dopamine. For those who are interested, however, social media may serve as a gateway to more authentic exchanges.

For Better and For Worse, We Must Use Social Media to Communicate the Realities of a Pandemic

The task of science communication is difficult enough even when messengers have the time, space and funding they need. It involves distilling results of invisible forces and complex calculations in a way that an audience can digest. Even when this information is presented to a relatively well-educated audience that is eager to learn, the uncertainty that lies behind every step of the translation—how well do lab experiments translate to uncontrolled real-world environments? What are the motivations and background of the people delivering the message? How well will the audience understand this message and communicate it to others? How does this message interact with our entrenched beliefs about the way things work? Who will be responsible for acting on new knowledge, and how will they interpret this message? Are these the most important questions to ask, and do we have the right people answering them?—is often understood implicitly and ironed out as innovation gets disseminated to the general public.

The health experts charged with applying our current understanding of coronavirus to pandemic policies do not know if or when a cure will come. The success of their strategies will be measured against counterfactuals. The costs will be physical, social and economic, wide-ranging and wrapped up in past and future failures in ways that preclude clear evaluation. That’s all more or less par for the course. However, these policies will be rolled out in a way that cuts off our traditional means of democratic deliberation. Shelter-in-place orders outlaw mass organization, fracturing means of interpersonal education and popular organization in the name of public interest. Quarantined within our bubbles, I don’t know how we’ll engage with the people outside.

On Tuesday, 17 March, Dr. Benton presented an hour-long webinar entitled “Can’t Touch This” to a digital audience of over 600 people. After introducing what was known at the time about coronavirus, she responded to questions from the audience. Asked what lessons we should take away from this pandemic, she said “it would be nice” to invest in global institutions, recognizing that “we are all linked by more than just trade and capital.” Over the past few weeks on Twitter, I’ve felt profound connections to complete strangers. We’re all making sense of what we’ve lost. We invent new jokes to stay sane. We share our appreciation for frontline health workers who have already gone through hell and have worse months ahead of them. We share heart-rending tales of loss, directions to local resources, and creative, colorful charts in hopes that they might be useful to someone who hasn’t seen the same tweet.

I prefer Twitter to other forms of social media because it is a place where the smartest people I don’t know issue unfiltered thoughts on the latest news. It’s a place where expressions of raw outrage and injustice from relatively anonymous people can reach an audience that rivals a president’s. My Twitter timeline reminds me that the world has always been broken; even if they can’t gather in person, victims of oppression can show strength in numbers through a hashtag, a trending topic that serves as a transient reminder that we have each other’s backs even if those in power do not. Twitter holds potential for new forms of advocacy for those who excluded from our traditional public spaces: people with disabilities, people who are incarcerated, people without homes, and other marginalized groups. It may be a far cry from the compassion and support we can share in the same physical spaces, but we won’t be able to get there for the next few months. More pandemics await us in the future; even after we find a miracle cure for the coronavirus, we may never go back to our pre-pandemic normal. In the meantime, we’re all going to be spending a lot of time on our phones. The stream of text, images and videos are no substitute for the compassion and connection I would have felt if I flew home, but at least they’re something.

Written on 20 March 20, revised in mid-April, finalized on 6 May

Morris Fabbri lives in Durham, North Carolina. He enjoys Settlers of Catan and Disc Golf, and he spends too much time on Twitter. You can reach him here: morris.fabbri@duke.edu