Far-right anthropologies

One of the things that surprised me most after I began doing research on European far-right youth activists was my research participants’ statements on how much they love anthropology. Not Mussolini, not Christianity, not philosophy, but precisely anthropology. “How dare you?”, I would comment on such statements in my head, assuming that they completely misunderstood what anthropology is about. For how can one love anthropology while hating the Other, or at least certain others? Doesn’t anthropology imply a sort of “love-all-the-humanity” approach, no matter how naïve this may sound?

Yet as it usually happens in ethnographic work, or at least in meaningful ethnographic fieldwork – the one that also forces us to turn the gaze towards ourselves and to reflect on our own positionality – I came to realize that I had to ask a reverse question: How do I dare question my research participants’ inspirations from anthropology? And why should I assume to know what anthropology means to them? After all, I would not make such an assumption about other kinds of claims or practices that anthropologists are trained to try to understand from research participants’ point of view: marriage rituals, values attached to labor, or ideas about God.

“I simply love Levi-Strauss,” Alberto, an activist from Southern Italy would tell me. In stating his fascination with Levi-Strauss’s travelogues, Alberto expressed the sense of loss that in his view characterizes modern times.

“I read Gellner and realized what nationalism is about,” Staszek, leader of a befriended Polish movement would declare, emphasizing his distance from ideological positions which fail to acknowledge the constructed character of nations (Later on, he asked me to share with him a copy of Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities). Leader of a movement that the Polish liberal press tends to describe as fascist, Staszek has been criticized by his collaborators for his supposedly too inclusive understanding of nation.

“One simply cannot understand the far right without anthropology!” Livio, a history student, would exclaim. Expressing admiration for my own professional path, he would explain to me that he temporarily abandoned school to create an independent mountain commune in northern Italy, inspired by what he referred to as “primitive societies.”

While his university colleague and highly devoted militant, Francesca, would state plainly: “I chose to become a far-right activist because I was always so interested in other cultures, in how differently people may live.” Such comments were often followed by, or even intertwined with, arguments about the need to defend European nation-states from (non-European) migrants, about the danger posed by LGBTQ movements, and, last but not least, about the need to protect the “cultural and racial diversity” of the human world. Yet if to me such statements appeared in stark contrast with claims about anthropology, to my research participants they constituted their logical continuation.

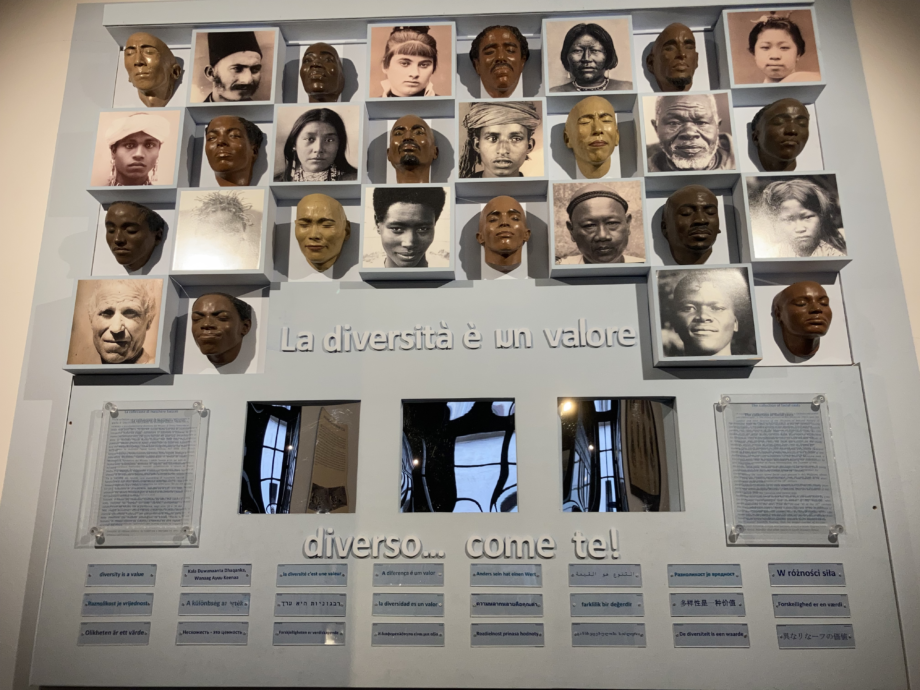

“Diversity is a value.” Tableau from Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence. © Agnieszka Pasieka

In this blog entry, I approach anthropology as a far-right emic concept and try to de-/re-construct its different meanings and usages. Rather than proposing an anthropology of racism, I focus on the usage of anthropology by the far right to justify their ideas of “race” and “culture.” In particular, I am interested in how far-right activists employ for this purpose a set of ideas they define as “anthropological”: views on (ethnic, religious) identities and ideas on what defines human (moral) beings. I draw here on the research with several European far-right movements (in Italy, Poland and Hungary) that I have been conducting since 2016. While a detailed description of the movements goes beyond the scope of this short entry, I shall emphasize that they all put forward a radical nationalist vision which blends nativist, identitarian conceptions with a critique of capitalism; and that while members’ professional paths are quite diverse, students and university graduates are among the most numerous.

In spring of 2021, Facebook profiles of my Italian research participants filled with the images of and commentaries on their new idol: a female American soccer player, Carli Lloyd. The player became known after she refused to ”take a knee” during the performance of the U.S. national anthem, as many athletes chose to do as a gesture of protest against anti-black police violence. In defending her act of refusal and praising her nonconformism, Italian activists did not challenge the existence of racism. Instead, they claimed that racism is “too serious a problem to be tackled by stupid performances” and – in criticizing the spread of the practice among European athletes – they emphasized that racism is an American problem.

In the same period, in response to a wave of events in support of Black Lives Matter, they organized a series of flash mobs throughout Italy during which activists gathered around an important monument (usually consisting of a standing figure or figures). The performances were accompanied by three kinds of slogans: #ItalianCultureMatters, #OurCitiesRemainStanding (#LeNostreCittàRestanoInPiedi) and #WeRemainHumans (#RestiamoUmani). The connection thus established – between the national culture, the refusal to kneel in opposition to racism, and the quality of being human – well exemplifies a tendency of the far-right to, in their words, “anthropologize” political debates. The Italian far-right’s attempts to defend their nation from “false” accusations of racism (it’s an American problem!) or from being “neglected” (the way they use the hashtag #Italian Culture Matters cannot but be seen as a variant of #All Lives Matter) are thus closely linked with ideas about human freedom, supposedly threatened by various new totalitarianisms. The slogan “We remain human” refers to a quotation from George Orwell’s 1984: “It’s not so much staying alive, it’s staying human that’s important.” In a commentary on the critical reactions to the female athlete’s refusal, one of the activists concluded that they represent not an attempt to impose an ideology or to generate and promote specific ideas about how the world works, but a project of “perverse anthropology” that aims “to shake human nature, starting from a psychological and social blackmailing” and challenging one’s right to act in accordance with one’s beliefs. They referred to the argumentation of the player, who explained that since she came from a military family she could not kneel during the anthem.

The second example refers not to a single occurrence but to annual celebrations my research participants engage in. With the veneration of concrete individuals and collectivities, far-right militants put forward their own project of identity politics, which they oppose to the “left-liberal” one, that in their view “only deals with selected minorities.” Consider these two statements by one of my research participants, circulated via social media and well representative of her milieu:

“People means identity, land, roots, belief.

Identity means customs, language, story, tradition.

Land is Homeland, blood and work, seeds and life, love and sacrifice.

Homeland is the home of those who worked that land, in the name of those who blessed it (…) Homeland is the land of resistance. Against the horror of Israel, honor to the struggle of the Palestinian people!”

“On 29 November 1864, a camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho got attacked by 700 American soldiers. … Native Americans were exterminated indiscriminately; many of them were mutilated and scalped. This episode is remembered as the massacre of Sand Creek.

There exist roots and identities, there exist the tie of soil and blood between man and his land; the tie that makes honorable people willing to die for this land.”

While accusing the “liberal left” of a selective definition of the category of “minority,” far-right activists I studied across Europe respond to it with a selective understanding of (honorable) “native peoples” whose resistance is to be venerated. The far right’s models for identity politics fall into two categories. The first includes victims of “imperialist politics”: Palestinians, Native Americans, the Irish Republican Army, and Cuban revolutionaries (the Cuban revolution is defined not as a communist but as a national one). The second includes Christian communities in religiously mixed regions, such as Armenia, Kosovo and Syria, which tend to be defined as “persecuted” and “forgotten.”

This somewhat romantic vision of identity – which blends Herderian views of culture with elements of anthropological approaches to ethnicity – is first of all communitarian, in contrast to the individualist view supposedly promoted by the “liberal left.” It features the rights of “peoples” (and their “cultures”) against the rights of the “abstract man.” In presenting themselves as real defenders of cultural diversity, militants simultaneously present themselves as offering an alternative to the “fake” radicalism of the left: its incapacity to embrace universal concerns, such as the right to belong, celebrate one’s ancestry, or work in the place of one’s birth. In making such claims, they refer to anthropology in two ways. First, to emphasize the universal importance of identity and the fact that people are ready to die for it; second, to highlight the value of particular, idiosyncratic identities that are to be preserved and which are, in their view, threatened by mass migration. In challenging the idea of societies becoming more diverse due to migratory flows, they consider the limited mobility to be a guarantor of the maintenance of cultural diversity and, to paraphrase Francesca, “many different ways in which people may live.” At the same time, while discriminating against Moroccans or Syrians living in Italy, the far right admires them as representatives of “strong cultures:” that is, cultures that migrants are proud of and to which they remain attached.

The third example also refers to a regular occurrence – the annual March of Independence organized by Polish far-right groups each November in Warsaw. After the event, organizers tend to respond via official statements and social media against the accusations of racism directed at them by the press and/or political authorities. The reasons for that are usually the banners they carry during the march and which feature slogans such as “Poland for Poles.” In responding to the recurrent accusations, members of one of the organizing groups stated: “Nation is a community of culture, not of blood. As nationalists and as Catholics, we affirm: a black person can be a Pole!” They further referred to their official declaration, which states: “In condemning biological racism, we postulate the maintenance of ethnic homogeneity, which helps to guarantee peace and stability”.

Quite unsurprisingly, however, claims regarding desired ethnic homogeneity lay close to those characteristics of (cultural) racism. For Polish far-right activists, it is likely easier to accept (one) black football player as a Polish citizen while Ukrainian migrants may be continually discriminated against, derided due to what the far right describes as “lower” cultural competence and described as threatening to ethnic stability and as a potentially insurgent force. Any discussion about migrants and refugees among far-right activists in Poland touches upon assimilation and the primacy of Polish national culture. Such arguments allow us to understand why an analysis of nation-states as projects and products, such as Gellner’s one, may be inspiring in shaping far-right movements’ agenda towards and discourse on ethnic “others.” In his major work, Gellner (1983) emphasized the importance of homogenous “High Culture” and the role of assimilationist policies in shaping nation-states, and, simultaneously, a likely push for political sovereignty by the excluded groups in case of the failure of assimilationist policies. In short, while “constructivist” understandings of nation clearly contrast with “primordialist” ones, they may be equally exclusivist: “common culture” may be as powerful tool of exclusion as the idea of “common ancestry.”

As these few examples demonstrate, the term anthropology appears to have quite different meanings to the militant far-right activists. “Anthropology” may stand for a certain vision or constitution of humanity; it may provide models of social coexistence through accounts of “primitive societies”; it may offer tools for understanding the reproduction of cultural difference. “Anthropology” and “anthropological,” declinated in all possible ways, seem to have entered the far-right vocabulary (even if different far-right dictionaries may define it differently).

No matter which understanding we take, it is easy to dismiss it as hypocritical. For how else would one approach the far right’s defense of cultural difference in a manner which does not revoke but rather reconfigures cultural and racialized hierarchies? Or, how would one approach a defense of humanity which seems have little to do with people’s rights? In short, it is easy to dismiss this set of ideas as a deeply illiberal project, the understanding of which seems to be quite straightforward: it places community above the individual, foregrounding the fundamental value of collective identities and attachments, and implicitly ranking “peoples” in relation to the presumed strength of their “culture.” As Douglas Holmes’s (2019: 83) observes when writing on new expressions of fascism, it is “an illiberal anthropology that can colonize just about every expression of identity and attachment … From the motifs and metaphors of diverse folkloric traditions to the countless genres of popular culture.”

Yet what if, instead of dismissing it, we placed this far-right engagements with anthropology under closer scrutiny? Not only because a better knowledge of “their” understanding of anthropology may provide us with tools for “undoing racism” but because it tells us something more about “our” anthropology (and, sadly, at times challenge the boundary between “our” and “their” ideas)? Such knowledge should force us to recognize the anthropological dimension of the arguments the far right puts forward, that is: to acknowledge the weakness of anthropological theorizing on culture, especially in relation to racism: to reconsider the relationship between illiberal ideas and anthropology; and foster a reflection on ethical implications of our engagement with far-right anthropologies. In the conclusions, I briefly address these three issues.

First, the way the notions of “race” and “culture“ are employed by the far right demonstrate the continuous operating of the racial categories within the discourses on culture, putting into question the arguments regarding the discourses of culture as replacing those on race (e.g. Stolcke 1995) as well as in the debates on “racism without race” and “cultural-differentialist racism” (e.g., Balibar 2008; Taguieff 1990). While a new wave of research on race as “absent presence” in Europe brings about highly inspiring theorizing on the continuous processes of racialization (e.g., M’charek and Schramm 2020; Balkenhol and Schramm 2019), these efforts do not seem to be matched by theorizing on culture (Visweswaran 1998). Meanwhile, after several decades of attempts to discard the concept all together, it appears clear that it is hard to “write against culture” without actually having a strong concept of culture. And more precisely: it is hard to deconstruct a homogenizing “culture talk” when ignoring the complexity of “culture-as-meaning-making” (cf. Abji, Korteweg and Williams 2019).

Second, a reflection on how a specific anthropological idea of culture travels, also into the far-right territories, should prompt a reflection on other troubling similarities and affinities. A growing number of scholars has been pointing this out. In her research on Brexiters, Ana Balthazar (2021:338) notes affinities between right-wing voters’ and anthropological discourses’ on saving traditional forms of life from the “ever‐expanding capitalist institutions.” In discussing the relationship between anthropology of populism, William Mazzarella (2019) and Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan (2015) talk, respectively, about a “populist stance” and „populist attitudes” inscribed into anthropological practice. More generally, an engagement with far-right anthropologies – similarly to the research on other “non-sympathetic” subjects – may constitute an important contribution to an understanding of the anthropology’s “love-hate” relationship with liberalism (Ansell 2019).

I would like to conclude with one final point which pertains more to methodology than to theory. In the opening words, I talked about ethnographic fieldwork as a way of turning the gaze towards ourselves by which I mean inculcating an openness to encountering irony, surprise, complicity, tools for self-criticism, to name but some. It is a problem hard to ignore for an anthropologist studying people who claimed to have fallen in love with anthropology. However, my push for an engagement with far-right anthropologies makes evident a tension marking such a stance, or rather: indicates both affordances and potential traps that adopting such a methodological stance entails.

By „traps“ I mean first and foremost a kind of misplaced progressivism that engagement with the far right can sometimes foster: on the one hand, for instance, through the possible argument of an obligation to empathize with the fears of „economically dispossessed“ and „politically disenfranchised“ people, or, on the other, through the overemphasis on the similarities between „us“ and „them“ – who also read, and read anthropology for that matter! In fact, however, it is precisely this particular distinction that is problematic: in my view, what a good analysis of the far right should challenge is a clear distinction between the „suffering masses“ and the „leader-intellectuals“ who speak on their behalf. In order not to fall into such traps, I think it is necessary to better recognize and more clearly state the possibilities and limits of research on the far right – and of any ethnographic research for that matter. That is, how this research foregrounds the need for an openness to self-criticism and self-irony that can serve to reflect not only on our positioning or beliefs, but also on the theoretical apparatus we use. My arguments for a more thorough engagement with „far-right anthropologies“ should not be understood, therefore, as a statement about blurred or fuzzy boundaries, but rather as a call to sharpen them.

References

Abji, Salina, Korteweg, Anna, and Lawrence Williams. 2019. “Culture Talk and the Politics of the New Right: Navigating Gendered Racism in Attempts to Address Violence against Women in Immigrant Communities’.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44(3): 797–822.

Ansell, Aaron. 2019. “Anthropology of liberalism.” 10.1093/obo/9780199766567-0216.

Balibar, Étienne. 2008. “Racism Revisited: Sources, Relevance, and Aporias of a Modern Concept.” PMLA 123(5): 1630–39.

Balkenhol, Markus and Katharina Schramm. 2019. „Doing race in Europe: contested pasts and contemporary practices.” Social Anthropology 27: 585-593.

Balthazar, Ana Carolina. 2021. “Ethnography of the Right as Ethical Practice.” Social Anthropology 29 (2): 337–38.

Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

Holmes, Douglas. 2019. “Fascism at Eye Level: The Anthropological Conundrum.” Focaal 2019 (84): 62–90.

M’charek, Amade, and Katharina Schramm. 2020. “Encountering the Face—Unraveling Race.” American Anthropologist 122 (2): 321–26.

Mazzarella, William. 2019. “The Anthropology of Populism: Beyond the Liberal Settlement.” Annual Review of Anthropology 48 (1): 45–60.

Olivier de Sardan, Jean-Paul. 2015. Methodological populism and ideological populism in anthropology. In: Epistemology, Fieldwork, and Anthropology, ed. J-P Olivier de Sardan, pp. 133–65. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stolcke, Verena. 1995. “Talking Culture: New Boundaries, New Rhetorics of Exclusion in Europe.” Current Anthropology 36 (1): 1–24.

Taguieff, Pierre-Andre. 1990. “The New Cultural Racism in France.” Telos 83: 109-122.

Visweswaran, Kamala. 1998. “Race and the Culture of Anthropology.” American Anthropologist 100(1): 70–83.

Dr. Agnieszka Pasieka is a sociocultural anthropologist whose research explores the role of nationalism and religion in political mobilizations and social activism. She is currently a visiting professor at the University of Bayreuth and a research fellow at the University of Vienna. She is the author of Hierarchy and Pluralism: Living Religious Difference in Catholic Poland (2015). Her new book project focuses on transnational activism of radical nationalist movements in contemporary Europe.