Turkey’s engagement with its diaspora during the pandemic

Turkey is one of the top 10 countries with an emigration history. According to the Foreign Economic Relations Board of Turkey (DEIK), more than 5.5 million citizens reside abroad, 4,6 million of which live in Western European countries (DEIK 2016).[1] The emigration from Turkey has had various phases from labour migration to the exodus of political refugees. Accordingly, the population of Turkish descendants abroad consists of many different groups: Kurds, Turks, Alevis, Sunnis, secular and religious Turks, AKP supporters and the AKP critics.

Due to the different phases of emigration, the policy of the Turkish state toward Turkish descendants abroad also changed over time: there was minimum engagement with them in the 1960s, cultural and social support in 1970s, and a monitoring of their political activities in the 1980s and 1990s. However, since the onset of the AKP rule in 2002, a more comprehensive shift in Turkey’s engagement with these populations can be observed (Mencütek & Baser 2018), which has been called the „new diaspora policy of the AKP“ (Ünver 2013; Aydın 2014). In sum, the AKP „recognizes and claims its diaspora“ (Başer 2017: 236-237) and pursues an active policy of intensified engagement (Mencütek & Baser 2018) to promote identification with Turkey among the Turkish people abroad, thus emphasizing Muslim and Turkish identity (Aydın 2014).

There exist various explanations for why and how sending countries engage with their current and/or former citizens and their offspring abroad. These vary from nation-building interests, improving cultural connections, demanding economic support for the homeland, to encouraging political participation. Accordingly, state engagement consists of different mechanism and institutions, which can perform in economic, cultural, social and political domains (Ostergaard-Nielsen 2003 & 2016) The activities in these domains aim to build connections between the state and its (former) citizens and descendants abroad. However, within these processes, the members of diasporic communities are not only passive recipients of their homeland’s support; they can also be active agents. For example, the outreach policies can be a response to a demand from an organized and powerful diaspora (Ostergaard-Nielsen 2003, 2016; Smith 2003). Against this backdrop, in my research, I study the demands and voices of the Germany-based local counterparts of Turkey’s cultural policy, i.e. pro-AKP and Erdoğan groups and their perceptions of Turkey’s new engagement.

In this contribution, I discuss Turkey’s outreach during the Corona pandemic and especially how the Turkish diaspora perceived this engagement. Next, I will present two examples to highlight the interactions between the Turkish state and the Turkish diaspora abroad. These examples show how the Turkish diaspora supports the AKP and its policies during the coronavirus crisis and the ways in which the Turkish diaspora in Germany has been linked to the homeland as a part of the AKP’s new diaspora policy. Overall, during the pandemic, I could observe that support for Turkey and belonging to the homeland remained strong among the pro-AKP and Erdoğan groups abroad[2] despite the growing mistrust for the government by Turkish citizens in Turkey regarding the ruling party AKP’s transparency on the number of patients. On the long run, this might lead to a situation where support for the AKP in Turkey in the next election is lost, making the diaspora’s votes more critical for the AKP.[3]

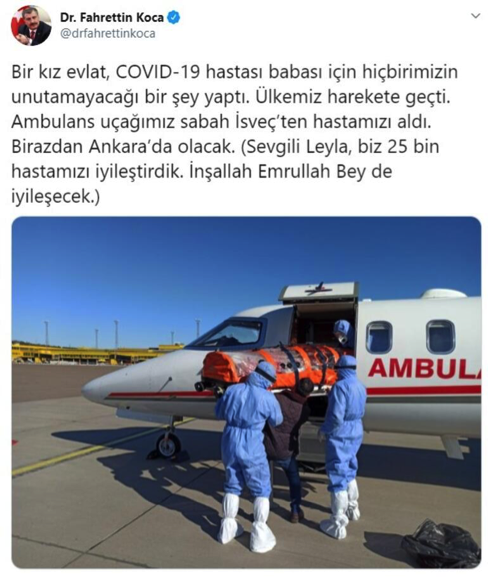

Picture 1: Turkish Minister of Health Koca reports that a Turkish citizen was transferred to Turkey from Sweden on 26 April 2020: “…We cured 25000 patients. God willing, Mr Emrullah will get better as well” Source: https://twitter.com/drfahrettinkoca/status/1254349419509579776.

Turkey as the protector of Turks abroad

Turkey provided help for Turkish descendants abroad “creating a caring image for all Turkish people” (Bortun et.al. 2020), for example when a Turkish man from Sweden was repatriated to Turkey in April 2020. According to some Turkish newspapers he was diagnosed with the Corona virus, but did not receive proper treatment in Sweden, and that his family had asked for help. As a response, the Turkish Minister of Health reported that Turkey sent an air ambulance to Sweden (see picture 1) in order for him to receive medical treatment in Turkey. This repatriation was criticized by some people in Turkey by stating that it was a show. For example, Durmuş Yılmaz, a MP from the newly found nationalist party in Turkey’s IYI Party[4] posted on Twitter: “… we have watched a Turkish movie, which was done unskilfully[5]”

However, the perceptions of this event were different. Indeed, my research interlocutors perceived the repatriation very positively. For example, one of my interlocutors shared the information on her social media, highlighting the developments regarding the patient’s transfer by posting a picture from the Turkish national television channel. This post was replied to by several positive comments such as “You are great Turkey!”, “May Allah give Turkey power!”, and also “May Allah does not leave us without a homeland and a state. Otherwise, what would happen to us!” These comments showed me that the people do not only celebrate “Turkey’s power”, but also perceive Turkey as a protector in times of crises[6]. This perception has played a role among my interlocutors even outside of the context of the pandemic. Several of them said to me that they had been left alone by the previous governments of Turkey, but with the AKP they are not “unattended anymore”[7]

Binding Turks abroad to the nation: support for “our state and our nation”

On 30 March 2020, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan started a “national solidarity campaign” named “Biz Bize Yeteriz Türkiyem (We are enough for ourselves)” in order to support Turkey’s fight against the Corona pandemic and to help people in need. The campaign was not only received donations from Turkish people residing in Turkey but also from those living in the diaspora. For example, according to Turkish newspapers, 70 years old Fatma Teyze[8], who has been living in Germany since 1972, has donated 10.000 Euro for the campaign. The well-known migrant organisation UID, which is defined by many scholars and journalists as the AKP’s lobby organisation, shared a video of Fatma Teyze. In the video, the head of the UID asks Fatma Teyze whether she needs anything and thanks her for her donation. Fatma Teyze answers smiling: „…I only hope [Allah] gives health and order our state and our nation. I do not want anything more from my God.“[9]

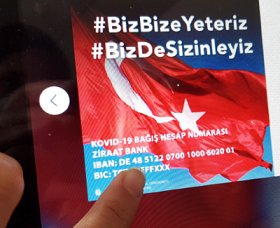

Picture 2: The information post for “national solidarity campaign” from Germany: #WeAreEnoughForOurselves and #WeAreAlsoWithYou. Source: https://www.facebook.com/unionofinternationaldemocrats/photos/a.660129137339007/3121294777889085/.

In a similar way, immediately after the campaign’s start, I witnessed that many of my interlocutors in Germany shared information about the campaign on their social media platforms, encouraging people living abroad to donate and show solidarity. Among them there were individuals, but also migrant organizations such as UID, who shared bank account details and pictures of the Turkish flag under the hashtag “#BizDeSizinleyiz (We are also with you)” (see picture 2).

In sum, the AKP aims to bind the Turkish citizens in the diaspora and their descendants to the homeland, which has to do with the fact that external voting is possible for the citizens abroad since 2014. Moreover, the AKP’s understanding of the Turkish nation surpasses the national borders as a part of the neo-Ottomanism, which foregrounds Muslim and Turkish identity and “refers to the ideal of being a regional power and … being as state responsible for all the Turkish people in the world” (Bortun et.al. 2020). Therefore, the examples I presented above can be seen as reflecting the AKP’s wider understanding of what it means to belong to the Turkish nation while living abroad.

Written on 09.10.2020 and revised on 12.10.2020

Sezer İdil Göğüş is a research associate in the Glocal Junctions department at Peace Research Institute Frankfurt. She is also PhD student in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the Goethe University Frankfurt. In her research, she focuses on i.a. diaspora politics of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Turkish diaspora in Germany. Contact: idil.goegues[at]hsfk.de

Footnotes

[1] For further information also see: Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Turkish Citizens Living Abroad” online: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/the-expatriate-turkish-citizens.en.mfa (accessed on 02.05.2018)

[2] Due to the lack of conventional observation possibilities, I collected the data on social media by observing the posts, comments and interactions between the people.

[3] The results of last municipal elections in Turkey indicate that the support for the AKP is decreasing. In 2019 municipal elections, the AKP has lost the three metropolitan cities Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir to the main opposition party. For more information, please see: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/23/erdogan-faces-scrutiny-once-more-as-istanbul-goes-back-to-the-polls

[4] IYI Party is a splitter party of the Turkish nationalist party MHP. MHP is an ally of the AKP, however the IYI Party is in the opposition.

[5] Durmuş Yılmaz Twitter, posted on 28.04.2020, https://twitter.com/DurmusYillmaz/status/1255119994746175488 (accessed 09.10.2020).

[6] The data is collected online. In order to protect the identities of people, I will not share the links. However, all the mentioned posts and conversations are collected by the author and are kept in an encrypted file.

[7] Informal talk, 21.08.2020.

[8] The names are changed in order to protect the identity of people. Also: Teyze means ‘aunt’ in Turkish and the way of using after the first name is due to the respect for the elderly person and also at the same time a sign for endearment.

[9] The statement is taken from the video interview posted online on the official Facebook page of the UID: https://www.facebook.com/unionofinternationaldemocrats/posts/3133042043381025 (accessed on 09 October 2020).

References

Aydın, Yaşar. 2014. The New Turkish Diaspora Policy, SWP Research Paper 10.

Başer, Bahar. 2017. Turkey’s Ever-Evolving Attitude-Shift Towards Engagement with Its Diaspora. In: Weinar, Agnieszka (ed.), Emigration and Diaspora Policies in the Age of Mobility. Springer International Publishing, 221–238 [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56342-8_14]

Bortun, Vladimir, Chaimae Essousi, Deniz Pelek, Nicolas Fliess & Eva Østergaard-Nielsen. 2020. Diasporas and initial state responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. MIGRADEMO Blog posts. [https://migrademo.eu/diasporas-and-initial-state-responses-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-3/]

Mencutek, Zeynep Şahin., & Bahar Baser. 2018. Mobilizing Diasporas: Insights from Turkey’s Attempts to Reach Turkish Citizens Abroad. In: Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 20(1), 86–105. [https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2017.1375269]

Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva. 2003. The Politics of Migrants’ Transnational Political Practices. In: International Migration Review 37(3), 760–786. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00157.x]

Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva. 2016. Sending Country Policies. In: Garcés-Mascareñas, Blancas & Rinus Penninx (eds.), Integration Processes and Policies in Europe. Springer International Publishing, 147-165 [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21674-4_9]

Smith, Robert C. 2003. Diasporic Memberships in Historical Perspective: Comparative Insights from the Mexican, Italian and Polish Cases. In: The International Migration Review, 37(3), 724–759. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00156.x]

Ünver, Can. 2013. Changing Diaspora Politics of Turkey and Public Diplomacy. In: Turkish Policy Quarterly. [http://turkishpolicy.com/article/619/changing-diaspora-politics-of-turkey-and-public-diplomacy-spring-2013]