Family memories, analog photographs and smartphones.

Reflections on a first experience of remote field work

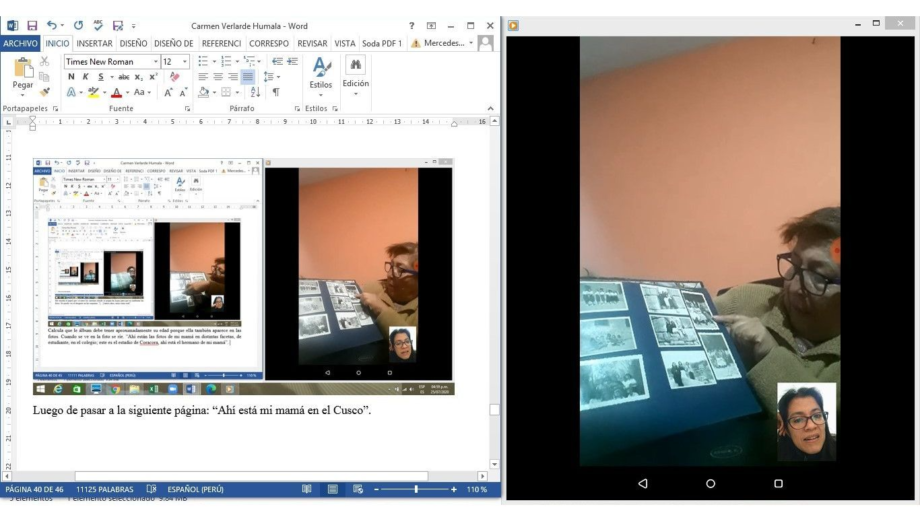

Image 1. Taken while transcribing an interview, this screenshot portrays Carmen Velarde showing me her mother’s album. We were talking about the presence and (re)viewing of family photo albums at home. Lima, 9 June 2020. Source: Image generated by the author and shared with the authorization of the interviewee.

I am 37-year-old Peruvian visual anthropologist in her first experience of studying in an international environment and about to conclude her first year of doctorate, which included a first period of field work in Lima (Peru). These have been challenging months in terms of personal, academic and professional adaptation. With the pandemic, as many researchers worldwide are experiencing, such adaptations have been re-dimensioned.

For some years now, my interests have revolved around the shaping of memories related to periods of political violence and reflection on the family photographic archive as an arena for research. My current research seeks to explore the way(s) in which family memories of police officers killed during Peru’s internal armed conflict (1980-2000[1]) are shaped. To do so, I propose to reconstruct theses family memories from a perspective of visual anthropology.

As an anthropologist, one of the aspects that I most enjoy about doing field work is the exchange with the participants of the research, manifested in the encounter with everyday knowledge, as well as in the development of moments and spaces of enriching learning. How can I achieve an exchange of knowledge and memories if I cannot visit my interlocutors? How can I approach the material archives in depth if I cannot access them? To what extent will my research objectives be reformulated? While it is not my intention here to give a definitive answer to such questions, the reflections I present are intended to address these epistemological issues.

An unexpected entry into the field

My research seeks to analyze the image of policeman killed during the years of the Peruvian internal armed conflict focusing not on their more public or media presentations but on those more familiar or domestic, as a way of making visible other stories in relation to the violence of those years. I start from recognizing memories of the violent past as an object of dispute (Stern, 1999; Jelin, 2002), which aims to pay attention to the active and meaning-producing role of its protagonists. Such disputes over the meaning of the past make evident the fractures in Peruvian society before, during and after the conflict. These battles, in turn, draw the political, discursive and representational framework in which all its direct and indirect actors operate. In these dynamics, however, not all actors have the same resources or conditions to participate or intervene. Thus, in these processes, some memories are more visible than others. Such is the case with the families of police officers who died during the conflict, whose memories are barely visible[2].

It is my intention to reconstruct and make visible the life stories of these people who are no longer among us. On the one hand, because such stories are important for their families and talk about them constituted a form of recognition: who were they, what do they want to tell us about their experiences? On the other hand, because these experiences can generate other reflections on the memories of the conflict, beyond those of their own institutions or those that are installed as officials. As mentioned, such constructions will be approached from an emphasis on the visual (Pink, 2006; Rose, 2010), mainly from: i) consulting family photographic archives (which implies considering family albums as field work places); ii) using photo elicitation technique in-depth interviews (Collier & Collier, 1986); and iii) observing the domestic spaces where family photos are exhibited and conserved.

The activities that I have originally planned for the first fieldwork stay in Lima, between the month of April and March 2020, included visits to potential research participants and interviews in their homes (located in different districts of Lima), with the consultation of their family photographic archives; visits to museum exhibitions of military institutions; and public commemorations, among others; and, if possible, contact a representative of these institutions. However, the day after my arrival to Lima, the Peruvian government declared the country in a state of emergency, establishing mandatory social immobility[3] at the national level and the closure of national borders from 16.03.2020. The Peruvian government has progressively extended the state of emergency, which continues to this day[4]. Consequently, due to these strict measures, I could not leave my apartment except for the most urgent errands and was able to return to Berlin on July 17, by means of a repatriation flight.

During the first weeks of social immobility, I made contact by telephone with potential research participants but felt that doing fieldwork was hardly possible. I realized I had to redesign my fieldwork strategy in a way that allows to carry it out in a remote way, but I was feeling really insecure about it. Watching the renowned digital anthropologist Daniel Miller in a homemade video, giving recommendations to doctoral students for conducting fieldwork during social isolation, implied an encouraging moment for me in this process. I thought that adapting interviews through digital means were the only option, but participant observation was also possible, which invites us to rethink different ways of doing it as well as of “be there”.

Getting to know family photo archives through WhastApp’s video calls

I conducted the interviews, which originally were to be carried out face-to-face, virtually by WhatsApp; one of the most used means by the interlocutors. This was challenging with regard to getting to know interviewees for the first time, talking about the sensible subject of family memories and viewing family photographs together. My first experiences with such virtual conversations were really positive and productive. I used a screen recording application that allowed me to have a register of the interview, with prior consent from the interviewers.

These virtual interviews required more time than initially envisaged, since people’s time schedules were determined by the lock-down and they were more available at night. Fortunately, because of my stay in Lima, interviewees and I were able to synchronize times more easily. To this end I conduct my interviews in various sessions (at least 3 per interlocutor) and select particular main topics and visual memories for each session.

As images 1 and 2 displays, WhatsApp’s video calls made also possible a way to „be there“. During our conversations, the family members showed me their albums and other photos they have at home, which made possible an encounter with this material culture relevant to my research. Moreover, the videos themselves constitute a new registration form for me, beyond the audio. These allow me to revisit the place that albums and family photos have in their domestic environments; which I used to be able to do only with previously scheduled visits. Even seeing my own face in the records, observing and „walking“ through such environments, guided by my interlocutors, invites me to rethink my presence as a researcher.

Of course, I also faced limitations and difficulties. For example, the different qualities of connectivity during the calls, the loss of records due to the malfunction of the screen recording application that failed me more than once, and the expertise in the use of the cell phone camera by the interviewees.

Image 2. Screenshot showing a banner with a photo of Roberto Morales, Sandra Garcia’s husband, in the living room of her house in Piura, Peru. Lima, 22 May 2020. Source: Image generated by the author and shared with the authorization of the interviewee.

As initial reflections

While this new virtual methodological approach may express the restriction of the activities initially planned, it also presents the opportunity to reflect on and generate knowledge concerning my research subject in the context of contemporary conditions of fieldwork. The forms of interviewing and observing that I described requires a methodological reflection, about not only the way in which the empirical data is being collected but also the nature of the data in itself (their register, transcription and processing).

To do so, I think it is important to discuss: i) the interaction with interlocutors through digital means of communication, who during our conversations share their memories and actions concerning family photographs; ii) an analysis of the camera setting of virtual conversations, in which we discuss family photos and portraits; iii) the generation of unexpected images, such as the screenshots of the interview videos and the visual record of my own presence, which also constitute empirical data; iv) finally, the expression and sharing of emotions about painful memories online is to be conceptualized. All these activities will allow me to approach my research objectives: i) register the discursive, visual and material repertoires of my interlocutors and ii) document the way in which family memories are involved in post-conflict processes and how they are represented.

Written on 2 October 2020 and revised on 8 October 2020

Mercedes Figueroa Espejo is a doctoral candidate in Anthropology by the Lateinamerika-Institut of Freie Universität Berlin and a DAAD scholarship holder. She possess teaching experience and research interests on fields such as urban studies, visual anthropology, cultural memory and heritage. Contact: mercedes.figueroa[at]fu-berlin.de

Footnotes

[1] In the early 1980s, the terrorist groups Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (MRTA) declared war on the Peruvian state, whose response, together with its armed forces, triggered an armed conflict that resulted in unprecedented violence in the country. As a result of this confrontation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR) estimated that there were approximately 69,280 victims, including the dead and the disappeared, in a period of 20 years.

[2] Families of dead police officers have little involvement in public discussions about what happened in Peru between 1980 and 2000. Nor have they been adequately considered as subjects of reparation by the Peruvian state during its post-conflict transition. They have a tense relationship with the police institution which, while it seems to give them a sense of belonging and pride, also seems to have forgotten them and does not recognize their rights.

[3] Also called “compulsory social isolation”, a measure that orders the population to remain at home from 18:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m., according to Supreme Decree 044-2020-PCM.

[4] The latest Peruvian government measure has extended the state of emergency until October 31st, according to Supreme Decree 156-2020-PCM.

References

Collier, Jhon & Malcolm Collier. 1986. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Mexico: UNM Press.

Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (CVR). 2003. Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Lima: CVR. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

Jelin, Elizabeth 2001. Los trabajos de la memoria. Barcelona: Siglo Veintiuno editores. https://www.academia.edu/24442775/Jelin_Elizabeth_Los_trabajos_de_la_memoria

Miller, Daniel. 2020. How to Conduct an Ethnography during Social Isolation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSiTrYB-0so. Last access: 28 September 2020.

Rose, Gillian. 2010. Doing Family Photography: The Domestic, the Public and the Politics of Sentiment. London & New York: Routledge.

Pink, Sarah. 2006. Doing visual ethnography London: Sage Publications.