The Limits of Negotiation

Some Thoughts on Public Anthropology and Critical Scholarship

Adorno: Theory is already practice. And practice presupposes theory. Today, everything is supposed to be practice and at the same time, there is no concept of practice. We do not live in a revolutionary situation, and actually things are worse than ever. The horror is that for the first time we live in a world in which we can no longer imagine a better one.[2]

Beginning a contribution on public anthropology by quoting Horkheimer and Adorno may seem unorthodox and controversial, even preposterous, for different reasons and different readers. However, this blog post was inspired by my recent reading of both scholars’ 1942 conversation on the relationship between theory and practice, published in English in 2019 as “Towards a New Manifesto”. Their musings on the possibility of critical scholarship in times of crisis spoke to me on many levels and made me combine several strands of thought that have been going through my mind in recent years. Consequently, this post discusses reflections on my limited yet formative experience with engaged public anthropology in light of the topic of this year’s annual conference of the German Anthropological Association (DGSKA) on the ‘end of negotiations’.[3]

I. On negotiation

The concept of negotiation (in German: Aushandlung) has always fascinated me. When I studied anthropology in the second half of the noughties, discourse on negotiation was omnipresent, especially in those fields that interested me the most, i.e. political anthropology, transitional justice, peace and conflict studies. Learning about social phenomena like the Pashtu Loya Jirga in the aftermath of the war in Afghanistan or the emergence of post-genocide Gacaca trials in Rwanda was fascinating and supportive of a view that the democratic negotiation of social orders was not a Western invention, but rather universal. In a more general way, the concept seemed to capture so neatly the expectations and hopes of an emerging global post-Cold War democratic culture. Whether this is something that holds true for Afghanistan and Rwanda, two societies characterised by very distinct cultures of oppression, is debateable and better discussed by other scholars. At the same time, however, in recent years the ‘West’ itself has obviously entered a slippery slope towards increasing authoritarianism, securocracy and politically institutionalised populist resentment.

It is in contexts like these that the term negotiation has started to give me mixed feelings. In anthropology, we use the concept to analyse, e.g., “constructions of reality and ascriptions of meaning […] during religious ceremonies, in refugee camps, or in scientific laboratories”, to quote from the announcement of the DGSKA’s conference.[4] The concept and what it aims to capture are of course comprehensible: people make sense of the world they find themselves in, all the time, for themselves and among themselves, and they negotiate their understandings of social reality even in adverse conditions.

In my opinion, what the concept, or rather, its too self-evident application quite often lacks, or maybe even obliterates, is a thorough analysis of the very conditions in which people find themselves. This refers to the social, political, and economic conditions under which people whom we as anthropologists observe and analyse make sense of their worlds and how their ability to negotiate social reality is limited and constrained by these conditions. It equally amounts, however, to the conditions that influence our own negotiation of world and meaning and that shape the environment within which our scholarship is taking place.

Any engaged anthropology ‘at home’ has to reflect on the critic’s positionality, as we have been sensitised to in the wake of Writing Culture, postcolonial critique and feminist anthropology. It also has to take into account, however, the institutional conditions under which (anthropological) knowledge, theory and critique are produced. In order to analyse the negotiation of issues like culture, belonging or identity in our own societies, especially under the impression of an increasingly polarised political and intellectual climate, we must not forget to look at where we stand ourselves.

Meaning, our analysis should also take into account our own quite often precarious status as scholars and university employees in an institutional environment that does not really encourage critique as academic practice, but rather valorises ‘excellence’, competitiveness and, ultimately, conformity. Questioning the structural conditions of academic knowledge production in universities, understood as institutions based on rigid status hierarchies, especially in Germany, and the increasing neoliberal commodification of research, still appears as a blank space of engaged anthropology. While at first glance this observation may seem trite, or even (worse) idealistic, it has consequences for scholars who practice what they consider ‘critical scholarship’ under precarious conditions.

In the following, I want to discuss a recent case study on the limits of negotiation; one in which I was involved heavily in a dual capacity as participant and observer. Instead of reiterating my analysis, which I have done in detail elsewhere (Kornes 2018, 2017, albeit only in German so far), I will present only a short retrospective summary of events. This will be followed by my personal assessment of some limitations of critical scholarship and engaged anthropology. Finally, I will discuss the question whether we, as engaged scholars and citizens, might actually find something worthwhile in the crisis of negotiation and the challenges it poses for academic practice, against all odds. Those familiar with what is called the ‘logo debate’ taking place in Mainz in 2015 may skip to part III.

II. On the limits of negotiation: a case study

In early 2015, the Department of Anthropology and African Studies (ifeas) at the University of Mainz (JGU) found itself embroiled in a controversial debate on everyday racism. The bone of contention was the corporate logo of the local roofing companies of brothers Karl-Christian and Thomas Neger, which, from the point of view of many critics, reproduces racist stereotypes of the colonial era. This critique has been repeatedly voiced publicly by ifeas scholars, including the author. A powerful activist campaign by JGU students ultimately brought this critique nationwide and even international attention. Despite the multidisciplinary authorship of the students’ campaign, ifeas became the object of a veritable digital media shitstorm, targeting students and staff in particular, as well as social anthropology as a discipline in general.

The controversial logo was designed in the 1950s and introduced by Ernst Neger (1909-1989) as a trademark for the family business. The company was established in 1909 and has since been run by the Neger family in the fourth generation. Currently, it is continued by Ernst Neger’s grandson, Karl-Christian, and claims to be one of the regional market leaders in the roofing business, with over fifty employees.[5] Thomas Neger, another grandson, has started his own roofing company using the same trademark. The company logo is therefore a familiar sight in Mainz and surroundings – whether on company vehicles or advertising banners, on construction sites in the city centre or on the JGU’s campus.

The logo depicts the upper body of a stylized black person, his right hand swinging a slate hammer as a symbol of the roofing profession. His lower body is covered by the shape of a pointed triangular roof, giving the impression of an exotic grass skirt. The facial features are particularly striking: with bulging lips, saucer eyes, a round hairless head and ears adorned by wide tunnels or ear plates, the logo clearly reproduces racialised stereotypes of black people as they were established in the 19th century under the influence of colonialism, especially in the field of marketing (Ciarlo 2011; Zeller 2008). The connection to advertising and branding prestigious colonial consumer goods is of special importance, since it is here that the iconography of racialised stereotyping was handed down from the days of the German Empire, the Weimar Republic and National Socialism to the popular and consumer culture of the Federal Republic of the 1950s. As I have analysed elsewhere, the roofing company’s logo is a particularly striking example of this (Kornes 2017: 98-104).

The combination of the aforementioned iconography with the family name Neger is what sparked the critique of the logo. In German, the word Neger has a slightly different connotation than either the English word n***er or the English word ‘negro’. In its meaning, I would argue, it combines aspects of the two, denoting both phenotypical appearance and a devaluating social category. Despite its obvious derogatory nature, many Germans still use the term in a descriptive way to refer to black people without actually intending insult. A prominent recent example was Bavarian Minister of the Interior, Joachim Herrmann, who called the popular German entertainer Roberto Blanco a ‘wunderbarer [wonderful] Neger’.[6] The use of such terminology reflects a deeply ingrained racialised cognition, present in many German minds, yet it should not be considered primarily as an intended insult. It was, after all, a racist compliment.

The second meaning of Neger, however, refers to the social category of the disenfranchised, colonised, dehumanised slave who is not ‘white’ and whose labour could be exploited for capitalist gain, legitimised by scientific racism. It is the invocation of this category, of course, that constitutes the insult for black people / people of colour in Germany when the word is used, regardless of the way its use is intended. And at the same time, of course, the word Neger is also used as a slur and insult on schoolyards, in soccer stadiums and digital media commentary, by people who are openly racist and primarily want to hurt.

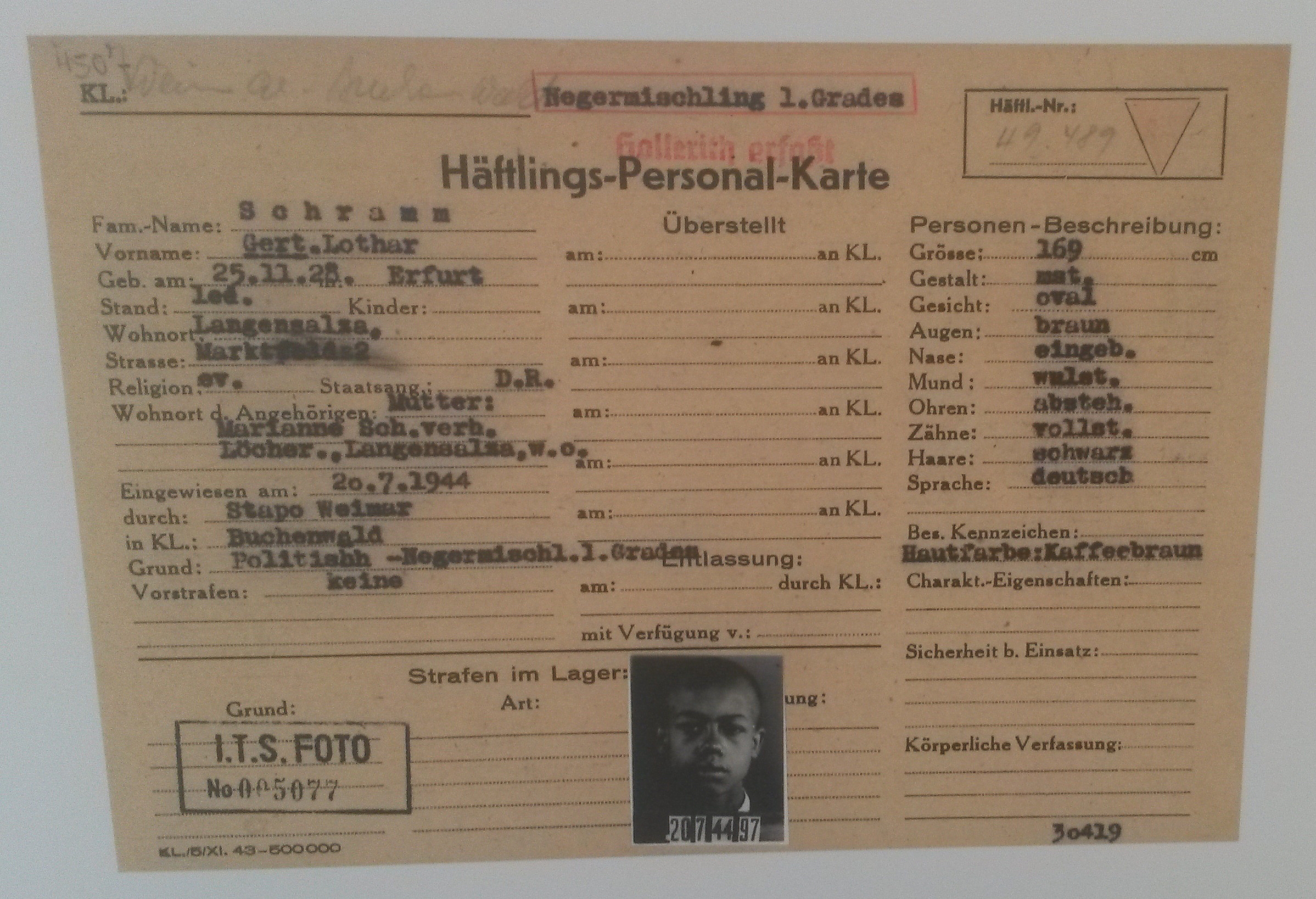

Prisoner index card from Buchenwald concentration camp (1944) (Source: Museum for Communication Frankfurt; Foto: G. Kornes). During the Nazi regime, black Germans were persecuted on the basis of the racist Nuremberg Laws (1935), imprisoned in concentration camps and in many cases subjected to forced sterilization.

By employing the historical iconography of colonial commodity racism, the logo invokes this derogatory category of the Neger, in order to visualise the surname of the company’s founding family, Neger. It was this use of a racist iconography to represent the family name that was criticised by activists and scholars, and not the family name, which actually is a vernacularized variation of Näher, referring to the profession of tailor.[7]

What added another layer of complexity to the debate was that the man responsible for introducing the logo, Ernst Neger, is a nationally revered icon of German Carnival culture, for which Mainz is particularly famous. Cherished as the ‘singing roofer’, Neger was a popular entertainer and has assumed the status of a local legend. His grandson, Thomas Neger, followed in his footsteps and combined the legacy of the profession with a career as a musician and has since become a popular figure in the local Carnival, too. This embodiment of family heritage, together with Thomas Neger’s political activity as a City Council delegate for the Christian Democratic Union, infused the debate about the company’s controversial logo with strong notions of localised identity and very particular political dynamics.

It was in this context that ifeas anthropologists supported the activists’ critique of the company logo by publicly explaining its problematic iconography and the historical connection of colonialism and everyday racism. This happened in the form of interviews with local and national media outlets, mostly conducted by Professor Matthias Krings, as well as my own participation on the grass roots level and in the digital media discourse. The company and its broad base of local supporters rejected the critique of the logo as misinformed and a result of, in a nutshell and populist framing, a campaign by leftist ‘social justice warriors’ bent on destroying the reputation of a respected local citizen and entrepreneur. In terms of ‘misunderstanding’, the company maintained that the logo actually was a parody of the family name that reflected the humoristic tradition of the Neger family; something the company’s critics were not able or willing to understand (Kornes 2017: 96f.).

However, the critique of the critique, brought forth by Thomas Neger and his supporters, including a number of local politicians, carried strong features of an attitude that resented the critical positioning of scholars, who were supposed to be ‘neutral’ and ‘objective’, depicting our critique as biased and unscientific. Amplified by the echo chambers of Facebook and Twitter and a legion of online trolls, ready at hand and fired up by the unfolding asylum crisis and emerging right wing populism, attacks on ifeas scholars and students became increasingly vitriolic. At the same time, anthropology was routinely discredited as, basically, a form of pseudoscience.

In hindsight, it is obvious that the dynamics of the debate inevitably escalated into a paradigmatic digital media shitstorm (Passmann 2018).[8] The boundaries drawn between activists and their critics became more and more rigid, as rival online communities emerged, fighting each other, and productive discourse became less and less possible. It was in this difficult climate that Matthias Krings and I tried to negotiate a position that allowed us to voice our critique, based on scholarship and reason, and to foster a dialogue about the critique. In this, we strove to reject the rampant hate that poisoned the discourse and to show solidarity with the student-activists without, however, agreeing to all of their statements, some of which we were critical of, too (Kornes 2018: 191f., 2017: 116-119; Krings 2018). One result of this endeavour was a face-to-face dispute between Matthias Krings and Thomas Neger, moderated by a local newspaper, which allowed them to exchange their respective positions; but the critique eventually faded out and the logo is still in use.

In retrospect, the debate appears as a vivid example of the limits of negotiation caused by a process of ideological rigidification and social closure in Germany, as well as the affective agitation it produces. It is in this context that a seemingly trivial object – the cringy company logo of a local roofing firm – could become a national issue and a projection screen for a variety of identitarian politics, from the far right to the left, across different social strata and infused with exclusive and strongly racialised notions of belonging.

Furthermore, the debate evoked and unveiled strong resentments against social science, pitting it against supposedly objective, ‘real’ science, which would not resort to value judgements. Ultimately, the debate functioned as a huge catalyst for drawing boundaries and group formation, which effectively limited discourse and the possibility to negotiate the very categories of belonging, apparently so important for all those involved. This highlights another limit of negotiation, our ability to engage with a public not willing to accept or even rationally consider the kind of knowledge that we as scholars provide.

III. Public anthropology and the limits of negotiation

For me as an anthropologist who engaged in this debate, motivated by a commitment to public anthropology and my reflection on our discipline’s ambivalent history when it comes to colonialism and scientific racism, the outcome is therefore double-edged. I appreciated the opportunity to engage with a wider audience in matters related to anthropology and to get first-hand learning experience in negotiating academic practice with the differing logics of journalism, activism, civic education and digital media.

During the debate, Matthias Krings and I had been working hard to negotiate our roles, and a lot has been done since then to process our experience and to generate knowledge out of it. Ifeas has organised a considerable number of events, lectures and exhibitions since 2015 dealing with racism and colonialism, routinely also referring to the logo debate (Kornes 2018: 191f.). I have published a number of articles (2018, 2017, 2015) analysing and reflecting upon my intervention, coupled with public events catering especially for a non-academic audience to sensitise it to the topics of everyday racism and colonial history. Matthias Krings (2018) has written about his perspective on the debate, and other scholars have contributed and discussed their ideas, support and reservations.[9]

The debate offered a broad range of insights into the prevalence of racialised thinking and the interplay of categories of difference like gender, ‘race’, class, origin, or education with identity and belonging. It also allowed participants to reflect on the potential and limitations of public anthropology and critical scholarship. Seen from this angle, engagement was a productive effort. There is a caveat, however, with several important aspects for critically engaged public anthropology to consider.

First, there was the fact that we experienced an insane and at times overwhelming amount of contempt and resentment, hurled at us in comments in digital media, letters to the editor or personal Emails (with people in most cases using their real names). The purpose of trolling, obviously, is to sabotage discourse and to hurt people. Even if one is aware of such dynamics, which have become part and parcel of our personal and professional digital realities, the insults still had their way of getting to one; they seeped in, slowly, doing damage. Serious health issues were one result of this, for me and others. It is important to mention this, since the effects of such ‘dark public anthropology’ – as one might call it, drawing on Ortner (2016) – tend to be overlooked or downplayed in the structural environment of academia, which does not cater to or even care much for the physical and emotional well-being of its human capital.[10]

Issues of health and well-being also affected several of the student-activists. It’s not an exaggeration to say that basically everyone directly involved in the debate left it damaged in one way or the other. The activists, many of them women of colour, gradually withdrew from public campaigning due to the extreme amount of racist and misogynist harassment they experienced online. In addition, and maybe inevitably, some friction and fission occurred, dispersing the core of the activists onto different political and organisational trajectories. As regards the company, it has remained immune to the critique and maintained its use of the logo. It is fair to assume, though, that for members of the Neger family the negative media attention caused a considerable amount of stress and misery, too – something that in all fairness should also be mentioned.

A second factor is the immense amount of time and resources spent dealing with media requests, interviews, letters and Emails written to us either supporting or rejecting our position. While a professor obviously has a very tight schedule and needs to carefully curate the time available for this sort of activities, he or she also has a fixed income and is practically non-redeemable. For grad students and academic staff on fixed-term contracts or stipends, engaged public anthropology presents a different challenge altogether, one with economic repercussions, which makes careful consideration necessary.

Third, this of course also relates to fears of how public exposure in the context of controversial issues can have a potentially undesired or even adverse effect on career trajectories and on our social standing in our academic peer group (which, I should add, was far from unanimously in support of our critical intervention). As Mertens has established in her insightful master’s thesis, for some early-career scholars (in German, Nachwuchswissenschaftler, a patronising euphemism basically obscuring existing precarious status dependencies), one very frequent result is self-censorship for fear of repercussions (Mertens 2014: 11). This leads to a situation in which mainly professors – that is, if they decide to do so – are the ones engaging in robust critique, simply because they can act with ‘impunity’, thus again reproducing the status hierarchies of German academia.[11]

However, as the recent example of another critical intervention has shown, even professorship does not necessarily protect against this predicament, when academic status is volatile. In early 2019, Raija Kramer, an African Studies Professor in a tenure-track position at Hamburg University, publicly criticised the German government’s official representative for Africa for a number of uninformed statements he had made about ‘African’ culture, politics and history.[12] Even though she voiced her critique in unison with a range of Africanist organisations and student groups, she was singled out by the individual in question and his politically connected peers and threatened with procedures to terminate her tenure track.[13]

Such a brazen attempt by politically powerful (male) state representatives to discredit a critical (female) scholar, with all its disturbing analogies to mob culture, may still be exceptional for Germany. It is one example, however, of the potential harm, economic repercussions and existential threat that may come with critically engaged scholarship (something those who inflict harm are aware of, of course). In Kramer’s case, positive media attention and solidarity was strong, especially within her faculty, while her employer, Hamburg University, at first appeared rather reluctant to publicly defend one of its scholars under attack.[14]

As a fourth point, it should be obvious that universities, as civil institutions, are structurally embedded in the political and economic realities that in turn have an impact on the setting of research agendas, on financing and on the influence of external actors on university policy. I do not want to insinuate that the good business relations that JGU Mainz enjoyed with the aforementioned roofing company at the time of the debate had an impact on avoiding making any official statement on the matter. I merely want to underline the obvious fact that universities’ purportedly apolitical and neutral commitment to the freedom of science inevitably conflicts with a multitude of vested political and economic interests, which shape the conditions under which scholarship is produced, supported or restrained. Universities reproduce ideology, social status and hierarchies, something that of course also affects the means of knowledge production.

This implies that critical scholarship may find itself not only at odds with a public that furiously refuses to be confronted with reason, but also in conflict with the university as an institution that tries to enable freedom of science while being entangled with structural conditions averse to making that freedom possible. This conflict represents what Horkheimer described as the irreconcilable divide between traditional scholarship and critical theory. Where the latter aspires to transform society based on the ideals of reason, the first is based on self-preservation, thus stabilising and reproducing the status quo with its power structures and status dependencies. Already in 1937, Horkheimer emphasised how, as a social process, every scholarship, whether critical, on the one hand, or neutral, fact-based and ‘objective’, on the other, is inevitably interwoven with the political and economic realities that shape the conditions for knowledge production (Horkheimer 1937). Where it takes its commitment to having a progressive impact on society seriously, critical scholarship must necessarily question these conditions and reflect on the way academic theory is to be put to use in the sphere of social practice.

Looking back on my experience of engaged public anthropology, I still find it difficult to decide which of the two challenges described above have been the more daunting: addressing an (at times openly hostile) public outside academia with critical scholarship, or negotiating the conflict between theory and practice under the conditions of academic knowledge production. In the final section, I want to propose my commitment for reconciling both challenges in the context of the limits of negotiation.

IV. Negotiating critical scholarship

A “sense of urgency”[15] for critically engaged anthropology was noted at this year’s meeting of the German Anthropological Association, which included several panels dedicated to right wing populism, migration and pertinent social issues, as well as the establishment of a Public Anthropology Working Group. This reflects a growing desire among anthropologists, also reported for German sociology (Hamann /Kaldewey /Schubert 2019), to counter the rise of right wing populism, fake news and burgeoning anti-intellectual resentment with the production of critical scholarship.

In recent years, German anthropologists have discussed the challenges of public anthropology as academic practice from various angles, often focussing on the uneasy relationship between anthropologists and journalists and the difficulty of providing anthropological knowledge suitable for the demands of popular media (Kornes 2017: 119-122, Mertens 2014). One primary concern of public anthropology is, of course, to bring anthropological knowledge into the public and to disseminate the research findings of publicly financed projects. Consequently, this discussion focuses on matters of pragmatism, resources and individual preferences in terms of academic public relations management. This kind of public anthropology is important and necessary. It is, however, different from critical scholarship that engages in, or sparks, debates on controversial issues and in doing so encounters hostile environments and public rejection.

The case of Thomas Hylland Eriksen is particularly insightful in this context. Often referred to as a kind of best-practice model of a public anthropologist, Eriksen has emphasised the unique potential of anthropology as being the “trickster” (Eriksen 2018) among the social sciences, a source of disruption and irritation for public discourse and policy. While this may seem inspiring to some and idealistic to others, we should remember that it was Eriksen whose engaged anthropology and outspoken cosmopolitanism earned him a place on the death lists of international right wing extremism. When neo-Nazi terrorist Anders Breivik in his crude white power manifesto explicitly referred to Eriksen as a sort of personal nemesis, critical scholarship got real to a point where it became existential.

Just to make it clear, I am not advocating for more (masculine) heroism in anthropology, quite the contrary. The point I want to emphasise is that critically engaged anthropology can have tangible and hurtful consequences (of which I and others had a small, but sour taste), which must be taken into account. If critical scholarship, as legitimate academic practice, is something that is desired, it needs an institutional environment that is dedicated to protecting its scholars and to safeguarding the principles of academic freedom. This applies at the level of universities, departments, faculties, and academic peer group structures. Where universities, as civil institutions entangled in political and economic double binds, are unwilling to provide support (which is not synonymous with agreeing to particular statements or critique), they must be actively challenged to comply. Where psychologically challenging research is done, as in some forms of anthropological fieldwork or extremism studies, measures should be provided for psycho-social supervision.

This is of special importance when it comes to awareness of the physical and emotional well-being of students and early-career scholars with vulnerable status dependencies. This must necessarily include a critical and honest discussion about hierarchies and power relations in academia as well as the dire employment situation of untenured scholars. Especially for the latter, who quite often are caught between a rock of academic demands to deliver and a hard place of existential angst, negotiating a desire to engage in public scholarship is difficult.

More focus should thus be placed on teaching, already at the undergraduate level, and on developing skills to navigate and negotiate academic practice in the context of highly mediatised social environments. Both undergrad and grad students should be encouraged to engage in public debates, to develop and articulate informed opinions and to address different audiences. This can mean visiting schools, engaging in civic education, organising panel discussions, producing digital media content or learning how to write in language accessible to a non-academic public. While a lot of this, of course, is already being done in undergrad teaching, grad students in Germany will find it difficult to engage in such activities along with their primary objective, i.e. earning their degree and competing in the game of excellence. Yet, since only a handful of anthropologists with a doctorate will realistically manage to secure a tenured professorship, such skills are of vital importance for competing in the non-academic job market.

But even within the context of public anthropology, this can become a challenge. Editing Wikipedia articles is most likely more effective in bringing anthropological knowledge to the streets than writing an op-ed for that renowned newspaper with its online paywall. But spending time on Wikipedia to popularise science is not a category of academic practice and thus not convertible into academic capital. Why not? Public scholarship (just like teaching, to be honest) should receive more recognition as a category that matters in academic career trajectories and tenure procedures. It should be promoted to an even greater extent as a normal part of academic practice, because there is real excellence in the daily grind of general education.

With its self-reflexive approach and its habit of critique, anthropology is predestined for critical scholarship. As the trickster of the social sciences, anthropology is in a unique position to irritate common sense and to produce an informed critique of our own society’s certainties about what is ‘us’ and ‘them’. Public anthropology should consciously seek its audiences, to groom an understanding for anthropological knowledge, but also be bold enough to face ideological headwinds and go where it hurts, especially in troubled times like these. We have answers, and people deserve to hear them, even if some of them fight tooth and nail to reject what we have to offer because it challenges their sense of self.

V. Conclusion

Horkheimer: “I do not believe that things will turn out well, but the idea that they might is of decisive importance.”[16]

Ultimately, it amounts to the question whether critical scholarship with the intention of having a productive impact on society, small-scale as it may be, is desired. The answer to this can be given only by us, as scholars. If the answer is positive, then universities, higher education policy and academic organisations must continuously be challenged to improve the conditions that make such critical scholarship possible in the first place. Public scholarship should be endorsed and supported, also and maybe especially where third-party funding from e.g. the German Research Foundation is involved.[17] Of course I am aware that it is not possible to turn universities into non-partisan institutions dedicated entirely to unlimited freedom of science, as if we could simply abandon the reality in which we find ourselves. However, we can and should strive to make our universities a better place for those of us who are of the opinion that theory and practice are non-exclusive categories, but instead provide in their duality the very foundation for any science that considers itself relevant for society.

If anthropology recommits itself to an analysis of the social, political and economic conditions, i.e. the material realities of the people, that determine and influence their capacities for making sense of the world, a critically engaged public anthropology will be more relevant than ever before. Against this background, the challenges posed by the limits of negotiation may actually result in something positive: the chance to rededicate ourselves to engaging with the social world and its conflicts, which are ours and which do not end when we enter the campus.

Godwin Kornes has been working as a research associate and lecturer at the Department of Anthropology and African Studies at the University of Mainz between 2010-2019. His thematic fields of expertise are political anthropology, memory studies and postcolonialism, with a regional focus on Southern Africa.

Footnotes

[1] Horkheimer, Max /Theodor W. Adorno, [1942] 2019: Towards A New Manifesto. London: Verso, 52.

[2] Horkheimer /Adorno, 72.

[3] The bulk of this contribution is based on a paper I presented at the Asien-Afrika-Institut at the University of Hamburg in July 2019: Kritik im Handgemenge? Überlegungen zur Positionierung der Ethnologie als ‘Parteiische Dritte’ am Beispiel der Mainzer Logo-Debatte.

[4] German Anthropological Association, 2019, “The end of negotiations?”, Conference Program, p. 8, https://tagung2019.dgska.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/DGSKA-Programmheft-Webversion-mit-Umschlag-1.pdf.

[5] https://www.neger.de/bedachungen/wir/geschichte.php?navanchor=2110005.

[6] This happened in September 2015, thus adding an insightful footnote to the debate about the roofer’s company logo, see https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/joachim-herrmann-nennt-robert-blanco-wunderbaren-neger-a-1050797.html. Hermann’s remark raises the question, of course, of what a ‘non-wonderful Neger’ might be.

[7] http://www.welt.de/vermischtes/article139189207/Die-Wahrheit-ueber-den-Namen-Neger.html.

[8] For a polemical, yet insightful analysis of the dynamics at play in a thematically related digital media shitstorm, see Sascha Lobo on the recent debate about allegedly racist statements made by German politician Carsten Linnemann, https://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/web/soziale-netzwerke-anatomie-eines-deutschen-shitstorms-a-1280856.html.

[9] See the debate in Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaft 2/2018.

[10] This may seem like a preposterous claim, but looking at it more holistically reveals a structural problem of universities to deal with difficult, threatening or even traumatic experiences scholars have in the context of their research; see for example Reyes-Foster and Lester on ethnographic fieldwork https://anthrodendum.org/2019/06/18/trauma-and-resilience-in-ethnographic-fieldwork/ and Allam on Jihadism Studies https://text.npr.org/s.php?sId=762430305. Unlike in Germany, British universities tend to have fairly rigorous fieldwork supervision management, see e.g. https://www.anthro.ox.ac.uk/safety-fieldwork-and-ethics#collapse389441.

[11] This, again, is reinforced by the dynamics and structural logics of media reporting, which tends to value the ‘authoritative’ contributions of professors over those of untenured scholars or students, see Kornes 2017: p.112.

[12] http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/afrikanistik/fv/down/Offener%20Brief.pdf.

[13] https://taz.de/Deutsche-Afrikapolitik/!5575963/.

[14] Apparently, the Presidency of the University of Hamburg has since promised to establish a working group aimed at documenting attacks on scholars and discussing measures to protect its academic staff (personal communication with Raija Kramer, October 2019).

[15] See Heike Becker on Twitter, https://twitter.com/HeikeBecker14/status/1181558848492060674.

[16] Horkheimer /Adorno, 31.

[17] For example, by making public relations projects in large-scale special research field (SFB) funding application procedures mandatory.

References

Ciarlo, David 2011: Advertising Empire: Race and Visual Culture in Imperial Germany. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press.

Eriksen, Thomas H., 2018: “Being irrelevant in a relevant way: anthropology and public wisdom”, in: Kritisk Etnografi 1 (1), pp. 43-54.

Hamann, Julian /David Kaldewey /Julia Schubert, 2019: “Ist gesellschaftliche Relevanz von Forschung bewertbar? Und wenn ja, wie?” Preisfrage der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 1-11, https://www.oeaw.ac.at/fileadmin/NEWS/2019/IMG/preisfrage/01_PF_2018-085_Kaldewey_Hamann_Schubert.pdf.

Horkheimer, Max, 1937: “Traditionelle und kritische Theorie”, in: Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 6 (2), pp. 245-294.

Horkheimer, Max /Theodor W. Adorno, [1942] 2019: Towards A New Manifesto. London: Verso.

Kornes, Godwin, 2018: “Der Streit um das Firmenlogo des Mainzer Dachdeckerbetriebs Neger. Chronik einer Debatte”, in: Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaft 2/2018, pp. 186-192.

Kornes, Godwin, 2017: “Zwischen Wissenschaft und Aktivismus, gegen den common sense: Zu einer Positionierung der Ethnologie als ‘parteiische Dritte’ am Beispiel der Mainzer Logo-Debatte”, in: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 142, pp. 93-126.

Kornes, Godwin, 2015: “Ein Kommentar über Rassismus und Menschenfeindlichkeit bei Ein Herz für Neger”, https://www.academia.edu/19650695/Ein_Kommentar_ueber_Rassis-mus_und_Menschenfeindlichkeit_bei_Ein_Herz_fuer_Neger_2015.

Krings, Matthias, 2018: “Identitätspolitik, allenthalben”, in: Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaft 2/2018, pp. 192-195.

Mertens, Michèle, 2014: “‘Warum sollte ich denn einen Ethnologen fragen?’ Über die (Nicht-)Präsenz ethnologischer Stimmen in deutschen Medien”. Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies, JGU Mainz 155.

Ortner, Sherry B., 2016: “Dark anthropology and its others: theory since the eighties”, in: Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (1), pp. 47-73.

Passmann, Johannes, 2018: “Shitstorm 2015”, in: Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaft 2/2018, pp. 211-214.

Zeller, Joachim 2008: Bilderschule der Herrenmenschen. Koloniale Reklamesammelbilder. Berlin: C. Links.