What I Have Learned from my Ban from the Humboldt Forum

First, let me attempt to explain why I received a museum ban. Indeed, a sensible decision that many have made has been to avoid going into museums completely, that is also a decision that I dabbled with for some time. Though to call it a decision would imply that my not going was a matter of choice rather than due to the fact that museums cater to a specific demographic — particularly White-middle-class families — who can afford the time and money. In the event that someone that looks, feels, speaks, and acts like me or, simply put, ‘non-white’ visits the museum, you are not a guest but, more often than not, an object amongst other objects.

I decided to visit the Humboldt Forum on 11/10/2021 at the invitation of my friend. We, both descendants of Ngonnso,[1] living in Berlin and intimately involved in the efforts for her restitution, decided it was worth it. I had initially resolved never to set foot in that building but when the opportunity did present itself, I thought of the thousand unholy white eyes that had been participating in this punitive exhibition and decided it would be good for Ngonnso to be looked at by eyes that saw beyond their material form. It was indeed a solemn occasion; I had gone to worship. I was also wary to support an institution that had built all its wealth and splendor on the labor, rape, looting, and exploitation of my culture and others like mine, to create stale alterity for whiteness.

When we entered the museum, in the first room, a cold dimly lit mortuary where subtlety was only one of the corpses, the welcome sign was an unapologetic declaration of whiteness. “I have a white frame of reference and a white worldview”. I was in shock, I contemplated leaving, but it was too late already, so, well, ‘what the hell’. We moved further into this dungeon and at once we became that world, unwillingly cast under this white perspective, not least because Ngonnso was displayed and seen through that white gaze, labeled as ‘art’ and discussed as an object, pointed at and imprisoned behind glass, but also because we became objects amongst other objects. Our bodies, lives, experiences, material and immaterial cultures as well as dreams and aspirations were the object of this museum’s monologue.

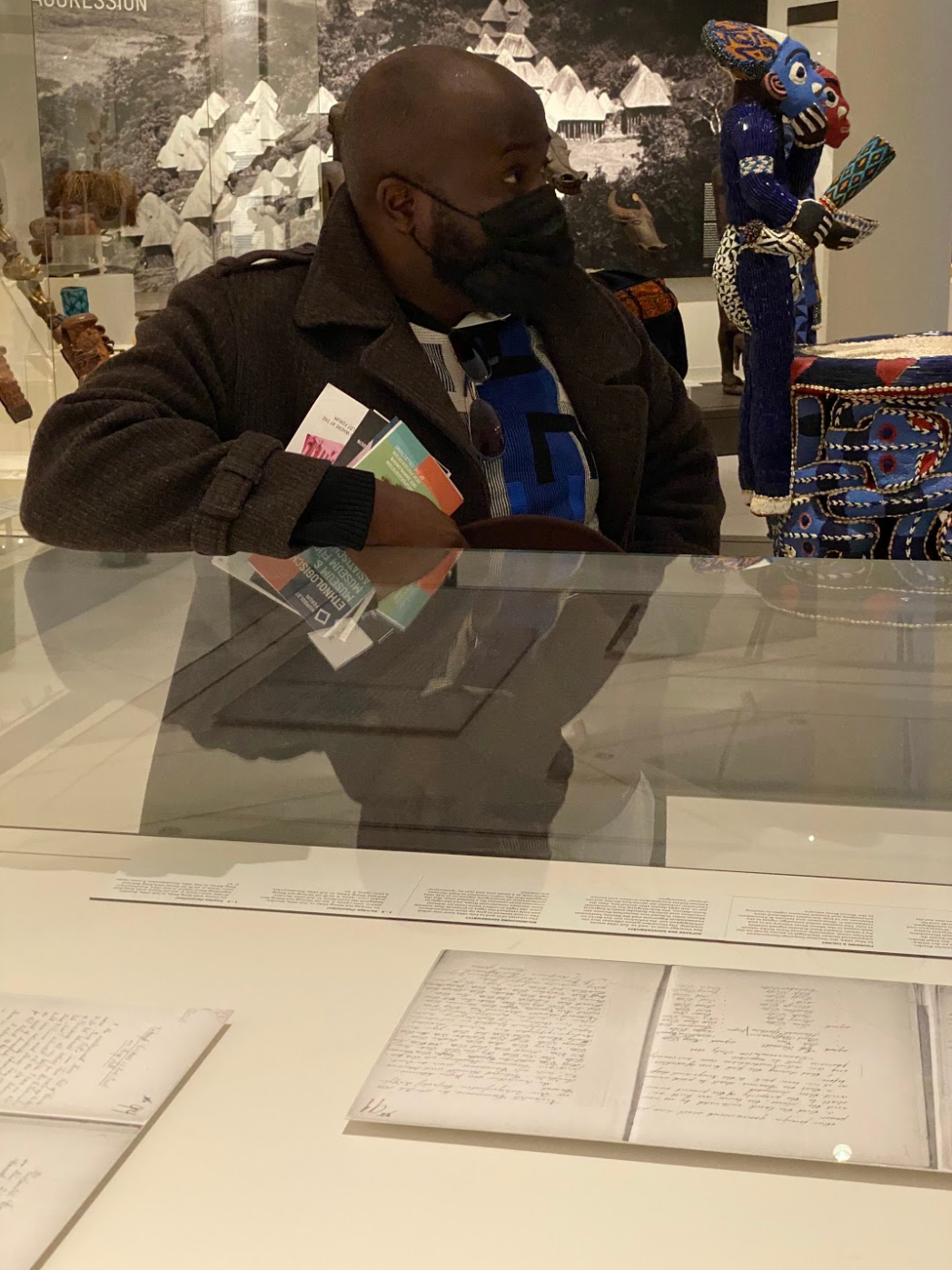

Figure 1: Temporary exhibition „Ansichtssache(n)“, organised by the Humboldt Forum Foundation on the premises of the National Museums in Berlin.

Copyright Wan wo Layir.

Indeed, I did not visit the Humboldt Forum as a tourist, and the sign made it very clear that I could not be a guest. I was there as a family member who was going to the laying in state of a loved one in the house their murderers had built and where their death was not an event but a continuity, one that was interrupted, reproduced, reenacted, and incomplete. I was struck by the fact that white people, here, were smiling, nodding their heads, twisting their faces in vain curiosity, and pointing with such great joy at the relics and corpses of my material culture, killed and looted by soldiers who were now glorified as ethnographers. They were looking to me as a native informant, functioning within the limits of the paradigm that if White institutions do not know about anything, then it does not exist. However, when these same institutions assert the existence of anything by knowing (discovering) it, the known must be both separate from the knowing and “collected” by the knower. this ability to take, to seize, to violently put things simultaneously into existence as conceived by Whiteness and out of their proper existence (context) must be celebrated and encouraged. The Humboldt Forum children’s section has a game where kids are tasked to find five objects hidden in the display, and the colonial soldiers who killed and looted are called amateur ethnographers, and their punitive missions that involved colonial, racist, and sexist violence is termed ethnographic collections.

The emotional and psychological toll such a visit takes on you is immeasurable; it is one I am still dealing with today. Yet, this was not the only thing we had to deal with, in the middle of a pandemic, standing in the master’s house, we also had to deal with the entitlement of white guests to our bodies and to our voices and stories in the same way these white structures were entitled to our material cultures. Indeed, “a lion does not give birth to a goat” as the Nso person would say. Throughout our visit, droves of white visitors followed us around like wasps drawn to ice cream on a hot Berlin summer day. Of course, we were their ‘native informants’, they did not consider us as guests. Social distancing and the caution of old German ladies who tell you at the supermarket that you are too close were thrown to the wind and they came to us like zombies touching and tugging on our shirts, pointing and asking “are those from your country?” (as if I could not be a Black German visiting the museum). Disempowered, unable to protest, being one of the few objects that could speak – however, extracted the speech was – we would respond, with nods, short histories of what we knew and the conditions of their arrival in Germany.

Figure 2: Exhibition of the Ethnological Museum of the National Museums in Berlin in the Humboldt Forum. Copyright Wan wo Layir.

I do not know if sympathy was what I expected from them, but the response they gave was as unacceptable as sympathy. “Oh, but it is beautiful, nuh, at least we can learn about your culture”, and I would reply with a heavy dose of sarcasm that would quickly turn sour on the lips when it went unnoticed that “Yes, true, I also learned about German culture because I had the Brandenburger Tor placed in a museum near my house in Cameroon”. As these conversations go, one party learns something new — because we must always remember that even black suffering is only seen through the very myopic lens of white self-progress — while the other is totally exhausted. We were the exhausted party.

In the middle of the room was an object that was definitely not Cameroonian, it was not even art at all, it was photocopies of old handwritten documents placed in a glass box. Valerie leaned on it while I proceeded to admire the beauty of the Mandu-Yenu.[2] At this point, a security officer who had watched the scene in Black Panther where Kilmonger ‘steals’ from the museum one too many times, and who had been following us around since we moved into the museum — and People of Color know this feeling from the grocery shop where black hair products are locked in shelves and you are a welcomed not as a customer but a thief until proven otherwise — hurtled over to us. He told Valerie that the documents in the box were indeed part of the exhibition. Upon closer inspection, they turned out to be photocopies of the German-Duala treaty, strategically placed without explanation in the middle of the room to justify the fact that Germany had the right to exploit Cameroon or, in the museum language, ‘collect’ the objects.

Figure 3: Exhibition of the Ethnological Museum of the National Museums in Berlin in the Humboldt Forum. Copyright Wan wo Layir.

Out of curiosity and fear, I asked the security officer what might have happened if the glass had broken while Valerie leaned on it. Disinterested in the conversation, Valerie moved on to other parts of the exhibition. The security officer told me that should that have happened, we would have either had to pay a fine or face imprisonment. Okay, now you must understand my disposition, this indeed went from zero to a hundred in one sentence. Looking around at the room we were standing in, the exhibition built out of killing, vandalism, and looting, I could not comprehend his response. So I asked him, in this place where murderers commit the crime of impersonating ethnographers, where genocide is masked as ethnology, and where looting and dispossession are considered collecting, what would then happen in the hypothetical situation where I brought in a hammer, broke that glass over there (pointing to Ngonnso) and brought that back to the people it belonged to. Would that be theft?

I love cliffhangers, do you? Imagine if I ended this story here. Actually, I am not even sure it would be well timed, maybe a better place for the cliffhanger would have been when the security officer approached us. Well, there was a little pause and I thought he had ignored my question, but when I saw his pale face flush with blood behind his mask, and his eyes began to go red, I initially thought he might have been suffering a heat stroke or something. He took deep breaths and asked “Are you threatening to break that glass?” to which I replied, “No, I am just discussing a hypothetical situation, where I would come in with a hammer and steal from a thief, would it be a punishable crime?”

Figure 4: Exhibition of the Ethnological Museum of the National Museums in Berlin in the Humboldt Forum. Copyright Wan wo Layir.

He took his walkie-talkie and called out “216” and almost immediately, 14 security officers approached me and escorted me out of the Forum. 6 came with me into the elevator, because that was the maximum that could go in, and took me to their security office where they took my information. Almost one month later, I received my official prescription for severe drapetomania.

The letter stated that I had touched objects in the exhibition and had threatened to cause a commotion. They were giving me the opportunity to defend myself till the 19th of November and I waited until that day to do it, not to defend myself, but to expose other criminals in the Forum. I was later invited to a meeting with them in January of 2022, and that will be the subject of another discussion as it was deeply interesting. After the meeting, they had proposed to lift the ban but I did not receive any document that said so, and, after an uncomfortably cringe and tiring email conversation, including threats and manipulation, they finally sent another letter that essentially said that they never banned me. Talk about gaslighting on paper without fire and gas.

While I process the meeting and the last letter, here is what I have learned from this experience:

The Humboldt Forum spared no rod when it came to teaching me my place. I would therefore say I am not spoiled but I still remain a Kulturbanause by choice. I have learned that museums are still a continuation of colonial military punitive expeditions. They are indeed punitive exhibitions, where the death of cultures, the looting of those cultures, the dispossession, eroticization, and objectification are constantly immortalized and continued. The museum, through restricting access, controls the narratives of those cultures and continues their exploitation and dispossession to feed the vanities of white audiences.

When access is however granted to those people — whose cultures have been exploited and killed, whose relics now effectively serve as constructions of otherness, that use the spiritual and material culture of Africa as proof of primitivity in an insidious and unforgiving process that robs Africa not only of its material possessions but of its contemporaneity — then the access is permeated by racism. Indeed, the objects in the museum are meant to reflect a world outside of Europe. Europe is the seer, not the seen, Europe speaks of the world and is not to be spoken about. The museum, of course, is aware of and co-opts anti-racist discourse to stop any further conversation and to sideline any demands for justice. They scream “we are on your side!” So the Africans visiting the European museum of African culture are expected not only to acknowledge this White gaze, but to embrace it and not question it so they may not be questioned. ‘Judge not, so ye be not judged’ is the definition clause of the contract that any Person of Color visiting an ethnographic museum in the heart of Empire signs.

The museum’s white guests remind you constantly that, though you might be in the house, you are not of the house, and its so-called collecting expeditions have left your culture robbed of its material substance and built a monument of gain on the loss of your material culture. When you do judge, when you do ask a question out of curiosity, the museum which already has control over time also takes control over space. You are boxed in; indeed, the security officers might have watched too much Black Panther and might have fantasies of being in an art heist, but you know the blatant racism is not just a result of their personal biases, but also of the institutional power that has allowed them to manifest.

You know that Ngonnso was raped because their sanctity as a spiritual subject has now been rendered profane and they are only an art object. But you are also painfully aware that this rape did not stop, indeed, the rapist has taken them and placed them behind glass so they can still masturbate to the actuality of that rape every time they see her there. This is what those ethnographic museums are, a kinky sex room built to satisfy the depraved vanities and fantasies of a shameless colonial class.

Other lessons abound and we shall discuss them in due time and through other experiences within and outside the walls of this splendid palace of horror where we go to die, next to our cultures buried in mass glass graves.

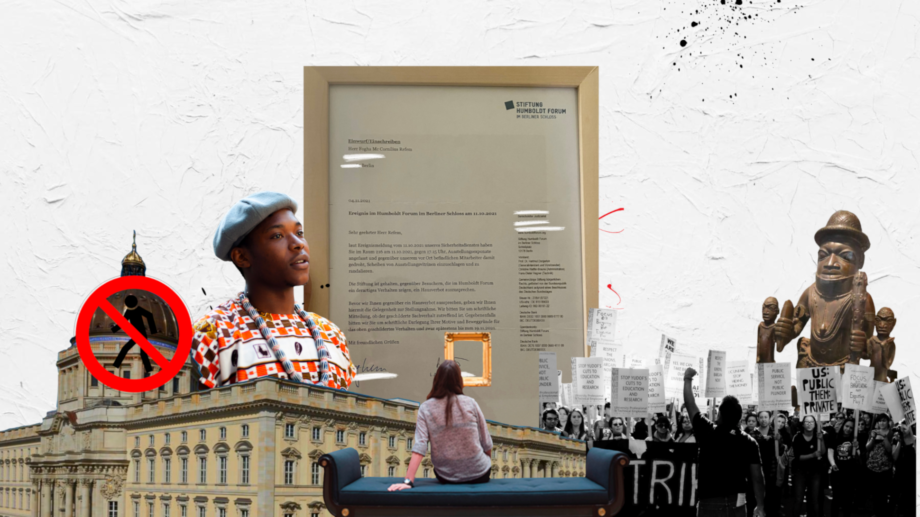

Figure 5: Collage made by the author for this blog entry. Copyright Wan wo Layir.

Wan wo Layir [from Lam’nso meaning „the child without a name“] is a self-prescribed severe drapetomenia “patient”. They are interested in decolonial futuries which they understand as an infinite succession of presents. They are an academic nomad with backgrounds in Sociology, International Relations, and Social Work. Their research interests include decolonial thought, subaltern studies, Black empowerment, and critical museum studies. They share their works/writing on the randomramblings blog https://www.randomramblings.eu/

Footnotes

[1] Ngonnso is the founder of the Nso dynasty and the guiding spirit of the Nso people, an ethnic group in the North West region of Cameroon. They migrated from Rifem in Tikari (the present day Adamawa Region of Cameroon), following a succession dispute after the death of Fon Tinki in 1387 under the leadership of Ngonnso’. Nso got its name from Ngonnso. Under her guidance, Nso formed alliances with other groups and became one of the biggest ethnic groups in the area. After her death, Nso spiritual life was organized around Ngonnso, the founding ancestor, in the same way she organized political and social life. This belief guided the Nso people to create a sculpture of her which was used for ritual purposes. This sculpture was looted from the Nso palace during a German colonial punitive expedition that involved killing between 700 – 800 people, burning the palace and taking over one thousand people prisoner in 1902. It was brought to Germany in 1902 and is currently being displayed at the Humboldt Forum.

[2] The Mandu Yenu throne was the throne of the Sultan of Bamum, according to the Humboldt Forum, Sultan Njoya of Bamum gifted the throne, a sacred symbol in the country, to the German Emperor Wilhelm II in 1908 to strengthen the relationship with the German colonial rulers.