The Puzzle of the Postcolonial Purse

Since the writing of this piece, the Amsterdam Museum of Bags and Purses has sadly been forced to close due to financial pressures exacerbated by the current crisis. This is a difficult time for all heritage organisations, and smaller institutions are always the most at risk. The closing of the Museum of Bags and Purses is a loss of a vital hub for those passionate about the subject. It will be much missed.

For far too long, the subject of dress has been dismissed as a secondary, ‘feminine’ topic. Other writers have listed in far greater detail the inherent gendered issues surrounding anthropological collections. With a predominantly male collector base, such collections lean towards traditionally ‘male’ interests, with a disproportionately large amount of weaponry and the like. At the other end of the scale lies dress[1], which far too often lies forlorn and bereft under the catch-all phrase “textile fragment”. Dress from non-Western cultures has long been regimented to the domain of anthropology, who in turn ‘marginalised the subject for decades[2]’.

This means that whilst the historical developments in Western fashion have been closely studied, much non-Western dress is lost within non-specialised anthropological collections. The first English-language encyclopedia of world dress was not published until the early twenty-first century, meaning that efforts to globalise dress history are still very recent. Dress history still largely adheres to this division of Western versus non-Western, leaving a vast knowledge gap in its wake. Into this falls the handbag, which suffers from marginalisation even within Western collections.

There is a lack of dedicated research anywhere in the field of bags. When writing my own MA dissertation on the topic, I struggled finding academic references and sources that explicitly discussed the handbag. They are a sadly under-represented topic in dress academia, which in turn leads to a dearth of information. Whilst working with the Victoria and Albert Museum for their upcoming exhibition on handbags, it was remarked that one of their greatest struggles when compiling object lists was that the museum never thought to include ‘handbag’ as a cataloguing reference. Much has been written on other female accoutrements – gloves, shoes, hats, etc.- but little attention has been paid to the handbag. The reason why precisely this is the case is the subject of another blog post, but what this means for the modern handbag academic is that one has to start very much from scratch.

This problem is only compounded when one steps outside of the well-documented haven that is Western dress history. What I faced when researching non-Western bags was a complete lack of information or knowledge. When I first started working at the Amsterdam Museum of Bags and Purses, much of the collection was poorly-documented. However, outwith of traditional European narratives, what immediately became apparent is that this information cannot be found. Many of the pieces came into the collection with little more than an estimated place of origin and material, but it is far easier to locate and source information about unprovenanced objects when they come from Europe and the West. Many come with labels or hallmarks, and much has been written on the way certain designers produce pieces. There are illuminated manuscripts from at least the 1400s with pictorial evidence of handheld bags, whilst at the other end of the spectrum, British Vogue has put every look from every season’s catwalk freely available online since the late 1990s. Whilst this information may not yet be centralised, for the dedicated Western dress or bag researcher, there is much that can be done with the information at hand.

I quickly tired of writing object labels with less information than the paper they were printed on, and reached out to anthropological museums in the hope that there might be further information out there. The responses I received were illuminating. Not one of the museums I contacted had any knowledge on bags, and one went so far as to tell me that it would be a whole research project in and of itself.

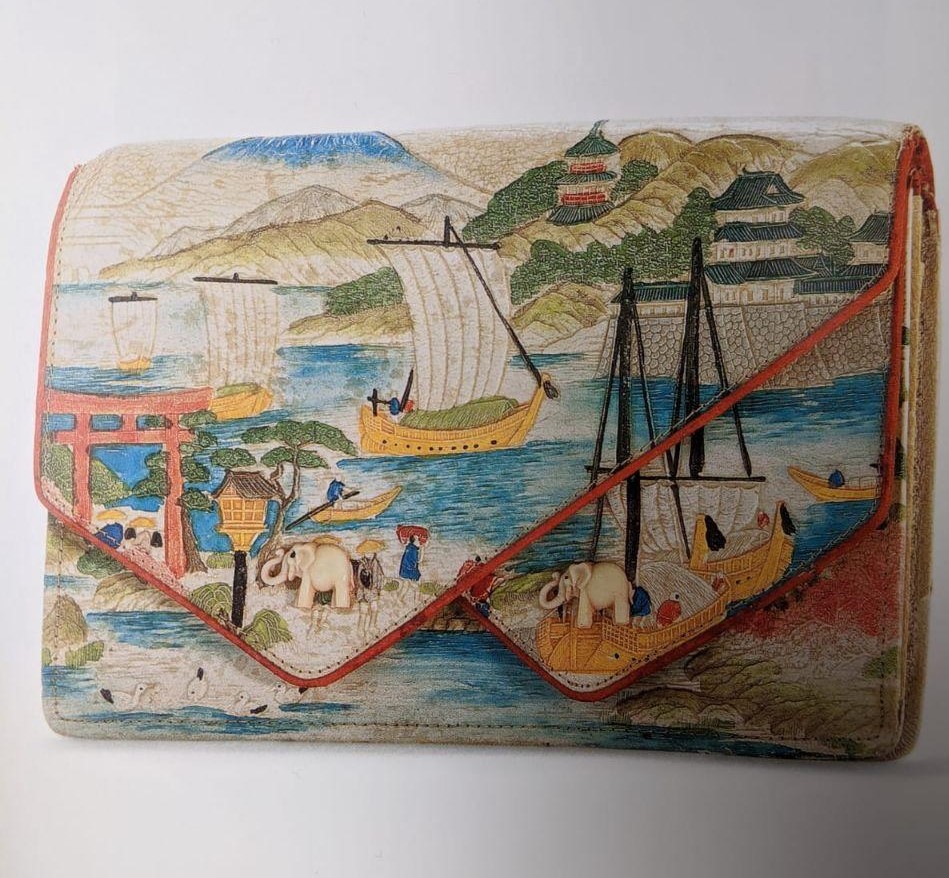

Leather clutch with embossed Japanese decoration, Japan, 1925-1935.

(c) Museum of Bags and Purses, Amsterdam

One particularly enigmatic area was a collection of Japanese clutch purses, dated tentatively to the early 20th century. Made out of printed white leather (sometimes imitation leather), they were embossed with scenes accented in bright colours. Probably intended for the female owner, many had internal mirrors, and featured matching combs or notebooks. In the original presentation (the museum has since undergone renovation), these purses were displayed alongside other pieces from a broadly similar timeframe, under the heading of ‘souvenir bags’. This fit in with the wider narrative of pieces made specifically to sell to Western tourists in the latter part of the 19th century, with the boom in travel.

However, whether these clutch purses were indeed made for foreign tourists remains to be seen. For a start, none of the pieces had any marks in English. Most of the pieces in the ‘Souvenir Bag’ display had something on them demonstrating their target market, including beautifully embroidered evening bags from India, many of which listed the maker by name, along with the market and the city at which the pieces were sold. I have encountered Japanese bamboo baskets, made after the Second World War, all of which are stamped clearly with ‘Made in Occupied Japan’. However, the majority of the printed purses were entirely unmarked, with only a few bearing Kanji characters on the zips and fastenings. This suggested that they were not intended for the export market.

Another detail that caught my eye is the choice of scenes depicted on the purses. I am by no means an expert in Japanese iconography, but the images on the purses did not, to me, seem like images intended to appeal to tourists. Whilst we had Egyptian pouches emblazoned with the Pyramids of Giza, and any number of Mauchline-ware boxes showing the beauties of Scotland, the scenes on these purses were not quite so tourist-friendly. The museum has Japanese pieces from much later, and these all feature scenes along the lines of Mount Fuji and demure geisha. (There is also a collection of Pokemon wallets from the early 1990s, which may have been donated by a younger relative of the founders.) These are all recognisable symbols for Japan, easily discernible for a foreign tourist audience. However, this is not the case with these curious clutch purses. There were a number of pieces that bore similar motifs – fishing scenes, figures with parasols under trees, and mountain ranges. Whilst beautiful, they did not appear to me to be illustrating a Japanese culture for a non-Japanese audience. Tantalisingly, my suspicions were in some way confirmed by a visitor, who claimed that these pieces were bought and sold for the Japanese market alone, and claimed to have photographs of Japanese women holding such pieces in the 1920s. However, we never heard from him again.

What particularly frustrated me about these pieces, and is indicative of the wider problems surrounding research in this area, is that the answer seemed so close. These clutch purses are very recognisable, and the ones in the museum’s collection came from multiple donors over a long period of time. Our mystery visitor claimed to be a collector of such objects, and certainly pieces occasionally appear for sale at auction. However, I have yet to find any sources discussing such pieces. My lack of findings from this project demonstrated the want of existing knowledge in bags from non-Western cultures.

This, I think, is a sad absence. With my own limited scope of knowledge, I know how much a Western bag can demonstrate, and I hardly think a non-Western bag would be any less revealing. I’m fascinated by questions such as when bags were carried in any society, and their meanings behind it. Many of the pieces in the Museum of Bags and Purses were clearly made with some care and attention to detail, meaning that a simple label of ‘work bag’ or ‘tea basket’ is an oversimplification that borders on an untruth. I would love to be able to answer simple questions about who carried such bags, who made such bags, and why they were made in the first place. Handbags reveal a great deal about a society. Whether it is the jewelled minaudieres of the upper classes in the 1920s, or the logo-splashed totes of the 1990s, every bag tells a story about the carrier, and the society in which it is carried. Without recourse to or understanding of such stories, non-Western bags are therefore left to be dismissed purely as functional work objects, which in turn denies the agency of the people who carried them. And if anyone knows of a collector of 20th-century printed Japanese clutch purses, please, tell them a girl in Amsterdam is waiting on a call.

Catherine Buckland’s research interests centre around dress history in context, specialising in handbags and historical dress. The role of handbags in the museum was the topic for her thesis for her MA in Museum Studies at the University of Amsterdam (title: Schrödinger’s Birkin: Exhibiting the Liminal Handbag), and was inspired by her time working at the Amsterdam Museum of Bags, latterly as curator. She currently works for the Dutch dress history community, Modemuze, which is based in the Netherlands.

Footnotes

[1] The use of the word ‘dress’ throughout this article is a conscious choice. Other words used in this discipline I find imprecise: ‘costume’ brings with it the connotations of artifice, whilst ‘fashion’ is inherently tied to styles and trends. An item of dress, regardless of its fashionable nature, will always remain a sartorial object.

[2] https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/products/berg-fashion-library/article/bibliographical-guides/the-history-of-dress-and-fashion