The Museums of Black Civilisations, between History and Utopia

DCNtR Debate #3. The Post/Colonial Museum

Introduction

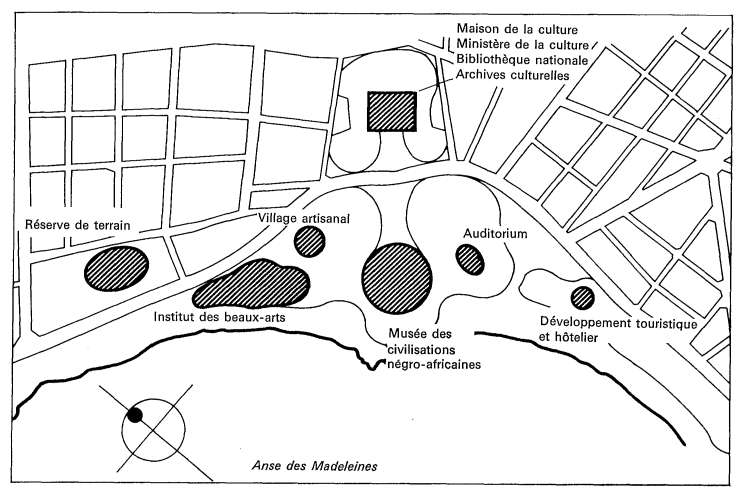

The idealisation of the Musée des Civilisations Noires (Museum of Black Civilizations, MCN) is attributed to Senegalese activist Lamine Senghor (1889–1927). It was in 1926, with the creation of the Comité de Défense de la Race Nègre (CDRN)[1] that the pan-African luminary firstly mentioned a museum for the preservation of African dignity and heritage. Forty years later, after the successful completion of First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966), president Léopold Sédar Senghor revisited this idea. The museum, designed to be »the most important cultural centre of its kind in West Africa« (Senghor apud Camara 2014: 40), was to be built on the Atlantic coast of Dakar, integrating a vast cultural complex accompanied by an arts and crafts village, a conference room, and a national library, among others. Then named Musée d’art négro-africain, the venue was to house pieces safeguarded by the Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire (IFAN), along with new ones to be acquired by the Senegalese state. Its galleries were to be guided by thematic and chronological itineraries, from prehistory to the present, and its mission was to challenge that of European museums built on the colonial experience (Camara 2014: 40).

Despite Senghor’s efforts, the museum would not come to fruition during his mandate (1960–1980), nor those of his immediate successors. Indeed, the Musée des civilisations noires, as it is now, is a result of more than four decades of negotiations that would come to a conclusion in 2015, due to the funds leveraged by Chinese soft-power strategies in West Africa [2]. »The development of the museum is part and parcel of an intellectual and cultural history of modernity«, claims Senegalese curator and scholar Malick Ndiaye (2019). »Reinterpreting that history in light of the profound changes it has entailed is therefore a challenge to the whole museological system« (Ndiaye 2019).

In this article, I examine the Musée des Civilisations Noires throughout three moments of its existence. Firstly, as an aspiration; secondly, as a project in the making; thirdly, as a fact. In the first section, I confront the expectations behind the project of the museum by positioning the institution in a broader geopolitical and historical context. This extends from the 1970s Mexican project of a cultural park, to the so-called »Seven Wonders of Dakar«, advanced during Abdoulaye Wade’s mandate (2000–2012). Following this contextualization, I demonstrate how the museum’s current public form grapples with ancient and current dilemmas on African art history and museology, with an emphasis on the »restitution debate« of 2018, initiated by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr. Finally, I delve into the highlights of the museum’s parcours and curatorial narratives in order to demonstrate how the MCN seeks to foster a vision of pan-Africanism that positions Dakar and négritude as the organizing tropes of Black history, assuming a central role among Africans and the diaspora.

Fig. 1: Musée des Civilisations Négro-Africaines in relation to the Dakar Ensemble Culturel (Lehmbruck/ Rautenstrauch 1974: 155).

Museum Politics, Past and Present

The history of the museum’s building starts in 1972, soon after UNESCO assumed the project’s sponsorship. It was then entrusted to the same architect who had signed the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Pedro Ramírez Vázquez (1919–2013). Senegalese curator and museologist Ery Camara was one of the key witnesses of such developments, as he closely followed the conception of the MCN from the beginning. At the age of 22, he was still finishing university in Dakar, when he was invited by the government of Senegal to study cultural heritage in Mexico City. It was intended that he joined the museum’s staff in the future. »My arrival in Mexico, in 1975, was prompted by the project of the Museum of Black Civilizations«, explains Camara (2014: 41). Throughout his training in Latin America, Ery Camara established a close relationship with Pedro Ramirez Vasquez.

The construction of the building did not see light under Senghor’s mandate, and was consigned to his predecessors. However, during Abdou Diouf ’s term in office (1981–2000) the project was undermined by the implementation of structural adjustment plans (SAPs). Many records related to the original project were lost; »the collections were left vulnerable in these uncertain conditions and many pieces were lost due to deterioration and theft« protests Camara (2014: 41). In 2003, with the arrival of Abdoulaye Wade to the presidency, the idea of the museum was re-established. Wade then contacted Ery Camara in order to resume the Mexican project for the museum, an invitation that the Senegalese curator promptly accepted. With still no feedback from Wade in 2010, Ery Camara travelled to Dakar to attend the second edition of the World Festival of Negro Arts. He came across a publication that featured the Museum of Black Civilizations as a creation of Senegalese architect Pierre Goudiaby Atepa: »an adaptation, or rather a plagiarism, of the original project« he stated (2014: 43). Camara then decided to bring public attention to the subject. As a result of this imbroglio, the Senegalese state put Ramirez Vasquez’s project to the side, and the MCN was then entrusted to the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (BIAD).

Camara’s account[4] was published in the Mexican magazine Gaceta de Museos (2014), four years before the opening of the MCN, and is remarkable for a number of reasons. Firstly, because it revisits floor plans, mock-ups and principles that guided the initial project for the museum. Secondly, because it points to fundamental aspects of post-war cultural relations between West Africa and Latin America, still little explored by academic literature. Finally, because it complexifies the well-polished narratives of cultural and artistic institutions nurtured by strong political positions, such as that of the MCN. As we shall see, the latter is absent from many of the public debates celebrating the birth of this important African museum.

As in the 1970s, the idea of a cultural park guided the ensemble of facilities retaken during Abdoulaye Wade’s mandate. Broadcasted on national television, the new constructions were dubbed the Seven Wonders of Dakar. In addition to the MCN, the project featured a new national theatre (opened in 2011), a national library, the national archives, a museum of contemporary art, the school of fine arts, the school of architecture, a music palace and the legendary statue entitled Monument de la Renaissance Africaine (Monument of African Renaissance)[5] »They are wonders in the sense that through their architecture and their meaning, they transmit messages through time to future generations« said Wade (apud Drame 2011).

Fig. 2: Atrium of the Musée des Civilisa- tions Noires (Dakar) three months before its opening (September 2018). Photo: Sabrina Moura.

Art Histories, Empty Rooms

I had the opportunity to first visit the Musée des Civilisations Noires a few months before its public opening[6] (September 2018), while its galleries were still uninhabited. On that occasion, I was in Dakar working on my PhD dissertation, which focused on the notion of diaspora at the Dakar Biennial[7]. I was attending the third edition of the Condition Report symposium series – Art History in Africa – convened by curators Ugochukwu-Smooth Nzewi and Koyo Kouoh, in partnership with the independent art space Raw Material Company. The gathering sought to foment a discussion of subjects, perspectives, and methods emerging from an art history written on, and from within, the African continent.

»The history of African art« declared Kouoh (oral communication, 2018) in her opening speech, »continues to be dominated by Western academics who set the tone for the subject. Their frames of reference, posed as universal, play on the interpretation of African art, social conditions, and cultural milieus. Besides, the audience for this kind of production is usually not in Africa«.

The call »to reconfigure the parameters and potential of art history in Africa«[8] as posed by the symposium, is not a novelty in African art theory and curatorship, being part of recurring impasses in the field since the second half of the last century. Indeed, it unpacks a series of paradoxes that encompass the Western origins of art history as a discipline, and are inscribed in the very concept of Africa, and its forms of writing. »We cannot think of an African-based art history from a dichotomous point of view, which isolates Africa from the rest of the world« stated Salah Hassan (oral communication, 2018) in his keynote speech for this symposium. In quoting historian Robin Kelley (2000), Hassan asserted that Africa and its diaspora were produced in contact with the West, in the same way that they have altered the artistic expressions of Western culture.

As these lively discussions unfolded throughout the meeting, speakers and members of the audience were having parallel conversations about what would be displayed in the vast empty galleries of the museum programmed to open in only a few months. At the end of the second day, a long-awaited conversation between Malick Ndiaye, Curator of the Musée Théodore Monod, and the MCN’s general director Hamady Bocoum introduced some aspects of the museum’s history and mission, without clearly defining the scope of its collections. Essentially, the debate concentrated more on the concept than the practicality of the museum.

»Why is this project coming back today, when it has been neglected for all these decades?« Ndiaye asked Bocoum (2018). After briefly drawing on some guidelines that framed its institutional and scientific project[9] Bocoum positioned the MCN as an experiment for the utopian reinvention of the African museum. He argued that its contemporary relevance relates both to the new place of Africa in global cultural geopolitics – which translates into an African-based museum that refuses to uphold a subaltern position regarding its Western counterparts –, and the epistemological reassessments of art history, ethnography and social sciences recently seen in the humanities.

»We have often been seen as subalterns, as a resonance chamber […]. I think that what can make the interest of this museum today is to see things differently. [That means] that it is very, very likely that if this museum had been built about thirty years ago, it would have been an ethnographic one. When we look at the trajectory of ethnographic thought – the study of the other – and ethnographic museums, [they] are copies of World Expositions that were presented to us a bit like saddle beasts, the other thing is that no one goes to ethnographic museums in Africa because precisely these museums are the reflection of a subaltern Africa.« (Bocoum, oral communication, 2018)

Just as Senghor had done in the past, Bocoum introduced the 15 thousand square metre museum as one of a kind. It was intended as a museum that would undergo constant change, with no permanent exhibitions or fixed narratives; it should find a balance between social interaction and artistic fruition in its circular Casamance-inspired architectural style; it should not fall prey to the traps of ethnography and othering; nor be exclusively dedicated to black people, but instead acknowledge the contributions of black civilizations to the »universal heritage of humankind«; it should honour the legacy of the First World Festival of Negro Arts… The list is long, and the stakes are high.

Once the debate had come to a close, the attendees and speakers went with Bocoum on a guided tour through the vacant galleries of the museum. However, instead of unravelling the museum’s mystery, that is, how those massive exhibition spaces would be inhabited in such a short time, the visit seemed only to aggravate the air of doubt that had filled the rooms.

During the Q&A session, one of the most poignant questions was posed by a young Senegalese art teacher in the audience. »What place will be given to contemporary African production, labelled as crafts (artisanat), in these new African museums? How will these institutions read, deal with, and preserve such practices?« she asked. Simply put, these questions summarize a number of issues regarding African museology and art history addressed by the symposium. On the one hand, they encompass an art perspective that challenges the logic of value attribution based on the primitivist (and formalist) legacy. On the other, they problematize the very concept of art that guides the foundational narratives behind this long-awaited museum.

Fig. 3: Baobab, Édouard Duval-Carrié Atrium of the Musée des civilisations noires (Dakar 2019). Photo: Sabrina Moura.

With the MCN’s opening[10], in December 2018, I came across the following headline in a local Brazilian newspaper: »The Senegalese Museum that wants to ›decolonize‹ African culture« (Nexo Jornal, December 8, 2018). The French Le Monde (December 5, 2018) stated: »the opening of the institution defeats the argument of the lack of adequate infrastructure in Africa, often opposed to requests for the restitution of works of art«. Like much of the international press, the inauguration of the MCN gave way to a series of celebrations, which indiscriminately mingled the political interests behind its execution and the high expectations around it. Before embarking on further considerations, however, I should note that the sceptical tone of the following lines in no way seeks to invalidate the significance of the MCN in the African and international museum landscape. Rather, it refers to the imperative of drawing a critical analysis of the self-laudatory discourses that underpin not only state-led institutions of this kind, but also Western anxieties regarding its own role in changing the course of African cultural structures in the current context of the debate on restitution.

In the introduction of his keynote speech for the colloquium Museotopia. Réflexions on the avenir des musées en Afrique (Museotopia. Reflections on the future of museums in Africa), June, 2019, the Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne stated »to- day, the question of the return of objects to the continent where they were born [Africa] questions the very meaning of such return, as well as the need to re-imagine the museum that would host them, in Africa and around the world«. Guided by the engaging word play that gave rise to the name to the meeting, organized by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr at the Collège de France (Paris), Diagne and his colleagues sought to reassess museological narratives, collections and structures, forecasting the future of these institutions. Such an exercise of critical imagination led to a radical interrogation of the relevance and the nature of museums in the 21st century. As one of the speakers, French anthropologist Philippe Descola (2019), would elaborate in one of the colloquium sessions: »What should museums be actually made of? And how should they be named?«.

Diagne’s initial take sheds light on his perspective on the translocation of African PPobjects to European museums. As he put it, these objects migrated from their »home- land« to Europe where they changed their status, from curiosities to ethnographic samples, and later from scientific to aesthetic pieces, widely intersecting with the visual grammar of modern Western figuration.

»A word about the radical rupture that most often would have been the forced migration to the museums of the colonial scientific expeditions, the ethnographic museums and, finally, the museums of the primitive arts. However, this is only a mutation whose possibility was indeed carried by the work in its infinite plasticity. These transplanted objects did not become mute in spite of this. Their mutant quality was expressed in the language of the ›negro revolution‹. Who will say that it was a misappropriation, that these works were made to speak against the intention that gave birth to them? The term primitivism renders them inert by making them the creation of Europeans who, weary of ›their ancient world‹, sought out a primitive that was in part their own invention. No, these objects acted as mutants and found their own way into a modernity they helped to create« (Diagne 2020: 109–110).[11]

It is not surprising that, in light of these considerations, the recently-inaugurated Musée des Civilizations Noires epitomized Diagne’s idea of a »mutant museum«, making it the highlight of the Museotopia (2019) conference.

With a view to explaining the importance I attribute to this excerpt of Diagne’s speech, let us turn, for a moment, to the report on restitution prepared by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy in 2018, at the request of French President Emmanuel Macron. As art historian Zoë Strother (2019) reminds us, one of its most-cited passages, within the public debate, refers to the observation that »almost all the material heritage of the African countries to the south of the Sahara is preserved outside the African continent« (Sarr/Savoy 2018: 3, emphasis added)[12]

The perspective of art and heritage sustained by the report, and the restitution de- bates vis à vis the MCN curatorial scope, must be subject to scrutiny. Especially when the theories underpinning recent revisions to art history point to a redefinition of its objects and subjects. In fact, Strother (2019) was one of the voices questioning the notion of »art« that permeates some of Sarr and Savoy’s arguments. For this, she took as an example her own research with the masked performances among the Eastern Pende. Described by the author as a complex chain of actions that encompass the memorization of music and proverbs, the learning of dance techniques, as well as the mastery of ritualistic protocols, the value of these practices is not restricted to the materiality of the artefact. By focusing on the object, only the masks used in these performances are considered to be art. »Such a selective view of what constitutes cultural heritage continues the colonialist paradigm that African cultural achievement should be defined by European criteria« Strother claims (2019: 5).

Malick Ndiaye, in turn, acknowledges that the gestures of restitution »must be consid- ered in both political and scientific terms« (Ndiaye 2019), and highlights the necessity to challenge the paradigm of the ›work of art‹ when addressing this agenda. »This tendency distorts the terms of the debate, insofar as it leads certain actors rejecting this legacy for the simple reason that it is a product of the history of Western taste, and therefore, should no longer be considered a proper African heritage.« (Ndiaye 2019: 5)

As previously mentioned, this debate was cleverly enunciated by the arts professor who was part of the audience of the 2018 Condition Report symposium, and is by no means a novel contention. In the 1990s, authors and curators like James Clifford (1988), Susan Vogel (1989), Christopher Steiner (1994) and Alfred Gell (1996) – supported by the contributions of contemporary art, performative and conceptual practices – already discussed the paradoxes related to the ties between art and artefact, art and matter, art and figuration. Their analyses gave rise to a series of experiments on the ways of exposing ethnographic pieces and the primitivist wave among European modernists, demonstrating that a non-object-based view of art offers important clues to fostering the establishment of collections in new African museums.

A Walk through the Museum Galleries

In March 2019, I was back in Dakar and keen on revisiting the MCN, now open to the public. My initial take was to follow the museum’s suggested path in order to underscore the narratives advanced by its scientific committee. According to the viewing sequence, the museum sections establish a parcours that begins at the centre of a circular-shaped atrium, occupied by a 12-metre-high bronze baobab, commissioned to Haitian artist Édourad Duval; allegedly, the only permanent piece on view (Bocoum 2018). Around the metal tree, the multiple galleries encompass a range of displays, from the so-called ›tribal arts‹, through the echoes of Abrahamic religions in Senegal, to contemporary arts.

The imposing bronze tree and its surrounding rooms emphasise the idea of Africa as the heart and the cradle of humanity, and marks the beginning of the visitation route. Here, a reconstituted version of the Toumaï skull is displayed along with explanatory panels on the continent’s contributions to architecture, agriculture, mathematics, and other sciences. This narrative inscribes Africa in a worldly perspective and in the longue durée, and was exhaustively discussed by a number of stakeholders in 2016 during the International Planning Conference of the Museum of Black Civilizations (Conférence Internationale de Préfiguration du Musée des Civilisations Noires). In attendance was historian and dean of the Cheikh Anta Diop University (Dakar) Ibrahima Thioub (2016: 13), who affirmed that »[…] humankind owes an immeasurable debt to Africa.« Indeed, the MCN opening galleries are a powerful statement in light of the continent’s position in the history of modernity, the transatlantic slave trade, and neoliberal capitalism. What follows however, is a missed opportunity to confront this positioning with Souleymane B. Diagne’s (2019; 2020) idea of a mutant museum.

Fig. 4: Les Lignes de Continuité and Femmes Noires et la Production des Savoirs Installation shots, Musée des civilisations noires (Dakar 2019). Photos: Sabrina Moura.

Pursuing the parcours of the lower left-side galleries, a section entitled Civilisations Africaines (African Civilisations) features a series of masks, statues, tunics, and other objects, presented as a sign of »African ancestry and authority«. While lacking contextualisation, this gallery proceeds without further addressing the pieces’ meanings (be they copies or originals) within the museum, or their role in Western and African art historiography. As the visitor continues to walk along the ground floor, a set of illuminated portraits emerges against a dark background. Titled Les Lignes de Continuité (The Lines of Continuity), it shows a number of black leaders, from Kwame Nkrumah to Barack Obama, and Frederick Douglass to Nelson Mandela. On the first floor, a similar display is dedicated to women: Femmes Noires et la Production des Savoirs (Black Women and the Production of Knowledge). Among the series of portraits, a photograph of American activist Rosa Parks (1913–2005) stands out. The representation of Parks and the great figures of pan-Africanism in the installation, included in the parcours of the MCN, immediately led me to associate it with one of the works exhibited in the seventh edition of the Dakar Biennial (2006), where the Senegalese artist Ndary Lo (1961–2017) chose to celebrate »the refusal of Rosa Parks«.

Fig. 5: The Refusal of Rosa Parks (2009), Ndary Lo, Fondation Blachère, Paris. Work recre- ated from the artist’s instal- lation at the Dakar Biennial in 2006. Photo: Laure Tarot.

Speaking in a radio interview in 2013, the artist explained that his interest in Rosa Parks began in 2005, right after her death: »I felt very moved by that lady. I started by making a portrait of hers, then a second, then a third… and, suddenly, I thought, I’ll make portraits of all the Rosa Parks of the world.« His words show that for many Africans based on the continent, the experiences of racial segregation linked to the black population outside Africa are an important subject of solidarity and political mobilization, just as for the diaspora. In the name of these connections, Lo included in his installation, in addition to Parks, a selection of portraits of other Black personalities, born in and outside Africa. Among them were Mandela, Angela Davis, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Bob Marley and even Okwui Enwezor (Andriamirado 2009, n.p.). »This work is entitled The Refusal of Rosa Parks, but I could have called it a ›pantheon‹. When I visited the Pantheon [in France], I reacted like a Black man, coming from Africa, and I said, we also need our Pantheon« claimed the artist (Lo apud France Cultures 2013). Be it a coincidence or not, MCN’s portrait galleries seemed to emulate Lo’s Black Pantheon.

In a third visit to the museum, still in 2019, I decided to take a guided tour with one of its mediators. The young guide was proud to present the city’s colossal museum to a foreigner visitor, and knew the curatorial parti-pris of each gallery extremely well. One of his favourites was, in fact, the illuminated portrait section, where we stood for almost half an hour discussing the current echoes of each figure.

Nonetheless, it is at MCN’s second-floor galleries that the museum actually honours its promise to be »one of its kind«. The first of these galleries, in a sequential order, is dedicated to the »African appropriations of Abrahamic religions« and is especially noteworthy as it offers elements representing a key dimension of Senegalese daily life. It includes reliquaries, Ayahs and portraits of spiritual leaders, such as Sufi saint Amadou Bamba or marabout Serigne Babacar Sy. Here, »Islam is Sufi – it is the Islam of sects and brother- hoods, presenting itself as a non-conformist, mystical tendency. […] It is a patient search for the union of the soul with God« states one of the exhibition panels. As one leaves this gallery, a corridor immerses the visitor in a video installation of moving waves in a deep blue sea. The principle, my guide explained, was to recall the Middle Passage and the forced African dispersions. On the occasion of my visit, at the other end of this passage, a temporary exhibition on Cuban contemporary art featured works by Marta María Pérez Bravo, Roberto Chile, Leandro Soto, and other artists, reinforcing the idea of reaching out to the Transatlantic diaspora. Following this sequence, the exhibition Maintenant l’Afrique presented the award-winning works of the Dakar biennial (Dak’art), including pieces by Fodé Carama, Soly Cossé, Dory Lo, Abdoulayé Konate. This was a veritable feast for those seeking a fine selection of African contemporary art hosted by an African institution.

Fig. 6: Maintenant l’Afrique Installation shot, Musée des civilisations noires (Dakar 2019). Photos: Sabrina Moura.

Final Considerations

This time, I left the museum convinced that the MCN should not be read solely by what it contains, but also by what it claims to represent in the landscapes of the continent and the diaspora. As Senegalese historian Iba Der Thiam (apud Bocoum & Ndiaye 2016: 21) stated, »the Museum of Black Civilizations must be […] a museum that reconstructs man (from Abel to Obama) and allows him to look into the future«.

Five years past the museum’s first public announcement, a report on Senegalese cultural policies, by diplomat and journalist Mamadou M’Bengue (1973), described it as an ambitious long-term project aligned with the nation’s future:

»Senegal is, of course, continuing to look ahead, since its cultural action concerns both the present and the future: as far as the present is concerned, it takes the form of constantly readjusting and developing the existing cultural structures, including training machinery and the necessary facilities for implementing the cultural policy drawn up by the government; for the future, it involves drawing up and carrying out cultural development projects forming an integral part of the national four-year plans and the long-term overall plans for economic development, which extend over a period of several decades.« (M’Bengue 1973: 64)

One should also note that the look toward the future is a key principle for the different expressions of Black emancipation, such as the African Renaissance. This conceptual and historical framework guided the gestation of Abdoulaye Wade’s »wonders« and included the Musée des Civilisations Noires, and its surrounding cultural park. The notion emerges between the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries amidst a circle of black intellectuals in the diaspora. Its early uses refer to the speech The African Regeneration, given by South African lawyer and politician Pixley ka Isaka Seme at Columbia University in 1905. »The giant is awakening!« proclaimed Seme. Later, in 1956, in the speech L’esprit de la civilisation ou les lois de la culture négro-africaine, presented at the Paris congress of black artists and writers, Sédar Senghor announced the African cultural »Renaissance« by overcoming the physical and symbolic losses caused by the Atlantic slave trade (Senghor 1956: 51).

Part and parcel of these debates, the contemporary version of the Museum of Black Civilizations recalls the glory of those intellectuals who rethought the meanings of Africa in history. As with the pan-African mobilizations in the past century, what is at stake with the MCN is an idea and a sense of Africa, its place in history and its position in the current global order.

I cannot end this analysis, however, without evoking the questions and positionings enunciated in the initial sections of this article. While the decolonization agenda or the recent restitution claims point to necessary debates related to the foundation of the MCN, the task of collecting should also be placed under the spotlight. Why has the MCN not been engaged in the establishment of its own collection? Which contemporary cultural expressions have not yet been validated by its gallery walls? How could they challenge an approach to art, which is focused on objects? And why are they not seen in this museum? If the MCN is to fully explore its institutional ambitions, it must put an emphasis on consistent curatorial research leading to long-term collection practices and new display strategies. All together, these initiatives can build a foundation from which the MCN can be positioned as a groundbreaking museum in the global landscape, as its precursors once dreamed.

This article has undergone a double-blind peer-review

All the translations in this article were made by the author.

The print version of this text is published in the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, issue “The Post/Colonial Museum”, 2022, p 107-122. In order to make the issue “The Post/Colonial Museum” available to a wide readership, specifically on the African continent, we decided to use the long standing collaboration between boasblogs and the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften to successively publish all contributions in print and online (as DCNtR debate). We thank the editorial boards of both, the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften and the boasblogs, as much as the publishing house transcript for embarking on this project together. Furthermore, our thanks go to the participants of the conference on Museum Collections in Motion, which was generously supported by the Global South Studies Center, University of Cologne, the research platform “Worlds of Contradictions”, University of Bremen, the Museumsgesellschaft of the Rautenstrauch- Joest- Museum and the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Most of all, we thank the contributors to this debate for four years of exchange, debate and intellectual companionship.

Footnotes

[1]The first black popular movement that brought together hundreds of members in France through the ports and major cities of the Hexagone« (Murphy 2015: 55, emphasis in the original).

[2] For a deeper analysis on Chinese foreign policies in Senegal see Gehrold/Tietze 2011.

[3] Assisted by Jorge Campuzano and Thierry Melot, and having the Swiss ethnographer Jean Gabus as its scientific advisor.

[4] In the 10th issue of the magazine Something We Africans Got (2019), Ery Camara elaborates on a second account which he names »the other story of the MCN«. Here, he overtly testifies to the contradictions between its curatorial project and political character. He states that he was initially part of the museum’s scientific committee, being invited to participate in the International Planning Conference of the Museum of Black Civilizations (Conférence Internationale de Préfiguration du Musée des Civilisations Noires), held in July 2016 in Dakar. »I had the opportunity in my communication to recall the original history of the project and its initiator. My intervention was in the direction of a deep reflection on the museum, its identity, its discourse, its program, as well as its anchoring within the territory. But I quickly understood that the main actors of the project were not in this perspective but rather in the urgency of responding to a well-established political agenda« says Camara (2019).

[5] Since its conception, the monument signed by Pierre Goudiaby Atepa – the same architect who had been accused of plagiarizing Ramirez Vasquez’s project, and who was now being charged by Senegalese artist Ousmane Sow – was shrouded in a series of controversies. From its production costs, which ran in the millions, to its being commissioned to a North Korean art production studio, to the representation of a ›normative ‹ vision of the African family. »May the symbol that [this monument] embodies and the message it conveys inspire, throughout the centuries, the peoples of Africa and the Diaspora, in our common search for a better destiny in a fraternal humanity« stated Wade (2010) in his inaugural speech.

[6] The museum was opened to the public in December 2018.

[7] Sabrina Moura. De volta para onde nunca estive: pensar a diáspora africana a partir da Bienal de Dacar (1992–2012), PhD Dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Brazil, 2020.

[8] See http://www.rawmaterialcompany.org/_2237?lang=en; date of pageview 23rd March 2022.

[9] These guidelines were drafted during the International Planning Conference of the Mu- seum of Black Civilizations (Conférence Internationale de Préfiguration du Musée des Civilisations Noires), held at the King Fahd Palace in Dakar, between July 28–31, 2016.

[10] The museum was inaugurated by president Macky Sall, in power since 2012.

[11] This reflection was first presented in a conference at the Collège de France organized by Bénédicte Savoy on June 11, 2019 and later reproduced in a written essay published in the journal Esprit (2020).

[12]According to Strother (2019): »The authors of a recent report on restitution prepared for Macron attribute this statistic to Alain Godonou, who estimated in 2007 that the ›inventories‹ of individual African museums ›hardly ever exceeded 3,000 cultural heritage objects‹.«

References

Andriamirado, Virginie (2009): »Le refus de Rosa Parks«, http://www.ndary-lo.com/tex- tes/rosa-parks/ (25.03.2021).

Bocoum, Hamady (2018): »Le Musée des Civilisations Noires: une vision d’avenir«. In: Présence Africaine 197: 1, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.3917/presa.197.0183.

Bocoum, Hamady/Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick (2016): »Rapport de la Conférence de préfigu- ration du musée des Civilisations Noires«, https://mcn.sn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ RAPPORT-CIP-1.pdf (30.03.2021).

Bocoum, Hamady/Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick (2018): »Le Musée des Civilisations Noires et l’histoire de l’art«, Condition Report 3: Symposium on Art History in Africa, Dakar, 20.- 22.09.2018, https://www.mixcloud.com/RawMaterialCompany/session-55-musée-des-civilisations-noires-and-art-history/ (25.03.2021).

Camara, Ery (2014): »Museo de las Civilizaciones Negras de Dakar: el proyecto de un lugar de memoria«. In: Gaceta de Museos 57, 38–43.https://www.revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/gacetamuseos/article/view/546.

Camara, Ery/Sy, Fatima Bintou Rassoul (2019): »Ery Camara et l’autre histoire du Musée des Civilisations Noires«, Interview, December 2019. In: Something we Africans got: 10, https://avril27.com/art-community/ery-camara-et-lautre-histoire-du-musee-des-civili- sations-noires-interview-f-b-rassoul-sy/ (26.03.2021).

Clifford, James (1988) : The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Lit- erature, and Art, Cambridge, MA/London : Harvard University Press.

Descola, Philippe (2019): »Table ronde«, Museotopia. Réflexions sur l’avenir des musées en Afrique, Collège de France, https://www.college-de-france.fr/site/en-benedicte-savoy/ symposium-2019-06-11-10h30.htm (25.03.2021).

Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (2019): »Musée des mutants (Keynote)«, Museotopia. Ré- flexions sur l’avenir des musées en Afrique, Collège de France, https://www.college-de- france.fr/site/en-benedicte-savoy/symposium-2019-06-11-10h30.htm (25.03.2021).

Diagne, Souleymane Bachir (2020): »Musée des mutants«. In: Esprit 7, 103–111. https:// doi.org/10.3917/espri.2007.0103.

Drame, Oumou Sidya (2011): »Projet architectural des sept merveilles de Dakar: Me Wade présente la maquette«, Xibar.net – L’oeil critique du Sénégal, https://www.xibar.net/PRO- JET-ARCHITECTURAL-DES-SEPT-MERVEILLES-DE-DAKAR-Me-Wade-presente-la-maquette_a32281.html (25.03.2021).

Gell, Alfred (1986): »Newcomers to the world of goods.« In: The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. by Arjun Appadurai/Cambridge/London: Cam- bridge University Press, 110–138.

Gehrold, Stefan/Tietze, Lena (2011) : »Far From Altruistic – China’s Presence in Senegal.« International Reports, November 13, 2011. https://www.kas.de/en/web/auslandsinforma- tionen/artikel/detail/-/content/kein-altruismus-die-chinesische-praesenz-im-senegal.

Hassan, Salah(2018): »Inand Outof Africa: African Art Historyasa Paradox!«, Condition Re- port 3: Symposium on Art History in Africa, Dakar, 20.–22.09.2018, https://www.mixcloud. com/RawMaterialCompany/in-and-out-of-africa-african-art-history-as-a-paradox- keynote-by-salah-hassan/ (25.03.2021).

Invité Culture (2013): »Ndary Lo, artiste sculpteur sénégalais«. In: Radio France Inter, 03.10.2013, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/emission/20131003-ndary-lo-artiste-sculpteur-senegalais (25.03.2021).

Kelley, Robin D. G. (2000): »How the West Was One: On the Uses and Limitations of Diaspo- ra«. In: The Black Scholar 30: 3–4, 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2000.11431106. Kouoh, Koyo (2018): »Opening speech«, Condition Report 3: Symposium on Art History in Africa, Dakar, 20.–22.09.2018.

Le Monde (2018): »Le Sénégal inaugure un Musée des civilisations noires à Dakar«, 05.12.20218, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2018/12/05/le-senegal-inaugure-un-musee-des-civ- ilisations-noires-a-dakar_5392879_3212.html (25.03.2021).

Le Monde (2018): »Le Sénégal souhaite la restitution de ›toutes‹ ses œuvres d’art« 28.11.2018, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2018/11/28/le-senegal-souhaite-la-restitution-de-toutes-ses-uvres-d-art_5389814_3212.html (25.03.2021). M’Bengue, Mamadou Seyni (1973): Cultural policy in Senegal, UNESCO.

Murphy, David (2015): »Tirailleur, facteur, anticolonialiste: la courte vie militante de Lamine Senghor (1924–1927)«. In: Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique 126, 55– 72. https://doi.org/10.4000/chrhc.4122.

Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick (2019): »Musée, colonisation, et restitution«. In: African Arts, 52:3, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1162/afar_a_00473.

Ramirez Vazquez , Pedro/Campuzano, Jorge/Melot, Thierry/Gabus, Jean (1974): »Musée des Civilisations Négro-Africaines« In: Musée et Architecture, UNESCO, 155. Rocha, Camilo (2018): »O museu do Senegal que quer ›descolonizar‹ a cultura africana«. In: Nexo Jornal, 08.12.2018, https://www.nexojornal.com.br/expresso/2018/12/08/O-mu- seu-do-Senegal-que-quer-%E2%80%98descolonizar%E2%80%99-a-cultura-africana (25.03.2021).

Sarr, Felwine (2016): »Rapport général de la Conférence internationale de Préfigura- tion du Musée des Civilisations noires.« In: Rapport de la Conférence de Préfiguration du Musée des Civilisations noires, ed. by Hamady Bocoum/Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick, Dakar, 28.–31.07.2016, https://mcn.sn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RAPPORT-CIP-1.pdf (30.03.2021), 105–113.

Sarr, Felwine/Savoy, Bénédicte (2018): Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle. France, Ministère de la Culture, http:// restitutionreport2018.com/ (25.03.2021).

Sarr, Felwine/Savoy, Bénédicte (2019): »Opening remarks«, Museotopia. Réflexions sur l’avenir des musées en Afrique, Collège de France, 11.06.2019, https://www.college-de- france.fr/site/en-benedicte-savoy/symposium-2019-06-11-10h30.htm (25.03.2021).

Senghor, Léopold Sédar (1956). »L’esprit De La Civilisation Ou Les Lois De La Culture Négro-africaine.« Présence Africaine, Nouvelle Série, no. 8/10 (1956): 51–65.

Simbao, Ruth/Kouoh, Koyo/Nzewi, Ugochukwu-Smooth/Sousa, Suzana/Koide, Emi (2019): »Condition Report 3: Art History in Africa: Debating Localization, Legitimi- zation and New Solidarities«. In: African Arts, 52: 2, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1162/ afar_a_00456.

Steiner, Christopher (1994): African Art in Transit. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Strother, Zoë S. (2019): »Eurocentrism still sets the terms of restitution of African art«. In: The Art Newspaper 308, 5.

Thioub, Ibrahima (2016): »Discours du Professeur Ibrahima Thioub, Recteur de l’université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar.« In: Rapport de la Conférence de Préfiguration du Musée des Civ- ilisations noires, ed. by Hamady Bocoum/Ndiaye, El Hadji Malick, Dakar, 28.–31.07.2016, https://mcn.sn/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RAPPORT-CIP-1.pdf (30.03.2021), 11–17.

Vogel, Susan (Ed.) (1989): Art, artifact: african art in anthropology collections (second Edi- tion), Munich, New York, Prestel.

Wade, Abdoulaye (2010): »Inauguration à Dakar du monument de la ›Renaissance africaine‹«, 04.04.2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbLXplepoxw (25.03.2021).

Sabrina Moura is a teacher, researcher and curator based in Brazil. She holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Campinas, during which she served as a visiting researcher at the Institute of African Studies at Columbia University, with a grant from the Getty Foundation (2016). Moura conceived and organized seminars and public programs presented by a number of institutions. In 2019, she was awarded a visual arts prize from the Cultural Action Program of the São Paulo State (PROAC) for the exhibition Arqueologia da Criação: Uma imersão no acervo-ateliê de Rossini Perez (Museu Lasar Segall, 2021). She is currently working on a long-term exhibition project on the permanent collection of the Museu Nacional da República (National Museum of the Republic, Brasília).