The Ethics of Repatriation and Working Collaboratively in Aotearoa New Zealand

The return of human remains back to descendant communities and countries of origin is a growing and developing part of museology throughout the world. Fifty years ago returning human remains or even cultural objects was almost unheard of. But in 2019 the return of ancestral remains and objects is increasingly becoming the norm.

In Aotearoa New Zealand repatriation is becoming even more common place. With iwi (tribal groups or nations) increasingly claiming for the return of tūpuna (ancestors) and a wide variety of taonga (cultural objects) as part of our countries’ treaty claims process, repatriation is now the norm.

This blog contribution is focused on the ethics of return and the ways in which we can be, and in some cases are, involved in new forms of cooperation with source/descendant communities throughout the world. But before I discuss the ethics of return, I would like to explore the ethics of collecting, as this will ensure a more holistic understanding of the issues relating to repatriation.

There is some controversy when comparing the ethics of today with those of the past, particularly with regards to human remains. Also, what is considered unethical in one country or culture may not be considered unethical for another.

However, as the quote by Pawnee elder Walter Echo-Hawk states: “Sanctity of the dead and their final resting place are NOT the exception to the rule” (Echo-Hawk 1998). What is meant by this statement is that respect for the dead is given to almost all people. There are of course exceptions, particularly in times of war. But as a general statement, when the dead are laid to rest, they are done so with love and respect, and most importantly with the understanding that they will remain at the site of their burial. With this in mind, let’s look at some examples of how the idea of ethics played a part in collection or rather theft of Māori ancestral remains.

Many of us understand that by today’s ethical standards the removal of any human remains without consent is deemed unethical. There are some examples, however, which show that even in 19th century Aotearoa New Zealand the ethics of collecting were questionable, especially when carried out by stealth.

As requests for examples of ‘native races’ came from museums around the world, during 1870 and 1880s, Thomas Cheeseman, director of the Auckland Museum, employed men in Northland to find and remove Māori ancestral remains, In a letter to Henry Flower at the Royal College of Surgeons in England he noted:

“The crania are from a Maori burial cave called Maunu, in the Whangarei district… . I have known it for some time, but until very lately some Maoris resided in the immediate vicinity, and kept such good watch that it would not have been prudent to have made an attempt to secure the skulls” (Cheeseman 1885: 285).

What this shows is that Cheeseman expected that the removal of the remains would have been opposed by local Māori, and therefore these men had to wait for the right time to sneak in and steal remains out of the caves. Was this seen as an ethical practice in New Zealand for the time?

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2012. Photo by Te Papa (64350)

Austrian taxidermist and collector Andreas Reischek who remained in New Zealand for 12 years (1877- 1889) became well aware of the feelings Māori had towards their dead and the consequences for removing ancestors from their resting places. The English translation of his journal reveals much about what he learned and his attitude towards Maori sensitives, particularly towards their dead and their burial places.

The journal is dotted with warnings from settlers as well as Māori, and even his own admission highlights the fact that his plundering was not accepted. He notes that “…natives threatened every violator of the grave-tapu with death” (Reischek 1952: 62). While in the King Country he endeavours to remove two mummified ancestors from a burial cave. He writes:

“The undertaking was a dangerous one, for discovery might have cost me my life. In the night I had the mummies removed from the spot and then well hidden; during the next night they were carried still further away, and so on until they had been brought safely over the boundaries of Maoriland. But even then I kept them cautiously hidden from sight right up to the time of my departure from New Zealand” (Reischek 1952: 215).

This own admission leads me to question his ethics, and ask if it is morally or even ethically ok to have collected under these circumstances, even by the standards of the day in Aotearoa New Zealand?

These two examples are just some of the many accounts which exist in Te Papa’s archives. But these stories do not just exist in Aotearoa, they represent the actions of 19th and 20th century scientists, explorers and anthropologists all over the world.

The ethics on the repatriation, restitution, or return of human remains back to their descendants is about reconciling these past wrongs. It is during this process that aspects of morality, consent, and even human rights are considered, discussed and reconciled.

Repatriation Pōwhiri (Matariki Willaims and Amber Aranui), 2017. Photo by Amanda Rogers. Te Papa (134095)

For the institutions who hold human remains, reconciling their own historical actions can sometimes be a hard pill to swallow. But increasingly museums and universities are coming to terms with the ever growing importance and role of repatriation in today’s museology.

Even New Zealand’s own National Museum is not exempt. As active as Te Papa is in repatriating Māori and Moriori ancestors from overseas institutions, we also have our own legacy of collecting human remains.

The Colonial Museum, which was established in 1865, began collecting ancestral remains the following year and within the first 10 years it had accessioned over 50 sets of ancestral remains from all over the country into its collections (Colonial Museum 1866). This of course does not include remains which were not formally accessioned into the museum but used in exchanges with other institutions around the world.

In 1867, 13 skulls were received by the museum by a Miss Catherine Bidwill. The inscription written on the skulls reads “Maori N. Island N. Zealand. From an old burial place that had been abandoned at least 20 years. In sand hills, Wairarapa Valley. J Hector 1868”. Two of these ancestors were returned recently from Yale University in the USA and the Charité in Berlin.

In order to reconcile the fact that these 13 ancestors were taken without consent, and then exchanged internationally by James Hector, Director of the Colonial Museum, Te Papa must now make this right.

Reconciling the past also happens at the grass roots level, with hapū (subtribe or extended family group) and whānau (family). In 2013, my team returned a number of ancestors back to Waimārama, a small isolated settlement in the Hawke’s Bay.

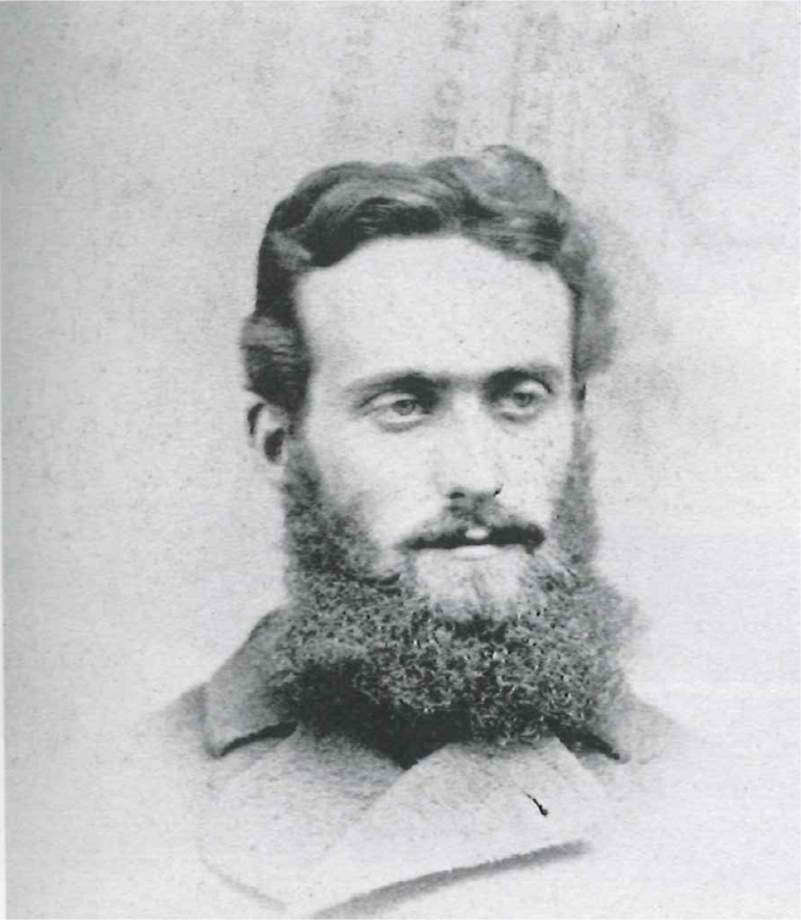

Frederick Huth Meinherzhagen,

In Starzecka, D., Neich, R., & M.

Pendergrast. 2010. Taonga Māori

in the British Museum. The British

Museum Press: London.

For me, this is an important example of just one way in which Māori are reconciling the past. The return of these ancestors was significant for this community as the collector was once part of it. Meinertzhagen was fully aware of the risks and his actions had he been found out. In his correspondence he notes,

“I regret I have not more to send you, but there are 200 maoris living on my run which is leasehold, and I cannot afford to run counter to their prejudices. You doubtless know how they respect the bones of their ancestors” (Meinertzhagen 1879: 2).

While living in Aotearoa New Zealand, Meinertzhagen also adopted a young Māori boy named Tame Turoa Te Rangihauturu, who later died of scarlet fever during the family’s return to England.

The return of these ancestors for the hapū evoked deep sadness. The knowledge that this man, who was accepted into their community, had desecrated their wāhi tapu and stolen their ancestors, coupled with remembering the boys passing, reawakened passed memories which still exist despite the fact that over 140 years had passed. Laying the ancestors to rest also allows for the past wrongs to be laid to rest and for forgiveness to begin.

Te Papa is also engaged in returning cultural objects back to communities and countries of origin. In 2016 an ahu’ula and mahiole belonging to chief Kalani’ōpu’u were returned to Hawai’i and now reside in the Bishop Museum. Those of us working in the museum see this return as important. Firstly, because these objects do not belong to us; and, secondly, because it strengthens our ties with our Polynesian cousins on the other side of the pacific. Most importantly, it is also ethically the right thing to do.

Aotearoa is committed to repatriation both nationally and internationally. This commitment, whether from the government, museums, or from individuals who understand the importance of this work, is reflected in a variety of ways.

From our countries early involvement from the 1980s through to the establishment of our government funded international repatriation programme in 2003, and more recent commitments by our government to domestic repatriation. I feel that our country is opening up and engaging in honest discussions around the ethics of holding human remains in Aotearoa New Zealand and also talking about and acknowledging our own part in the collection, trade, and exchange of human remains.

In 2018, I established the Kaihurahura Whakahoki Kōiwi Tūpuna o Aotearoa, also known as the New Zealand Repatriation Research Network. It is made up of members from 17 New Zealand museums who hold human remains and are open to and supportive of returning human remains contained within their collections. The purpose of this network is to share information, undertake collaborative research, and also to support and advise on aspects of physical and spiritual care, engaging with communities and coordinating repatriations together.

Earlier this year, our Associate Minister of Arts, Culture and Heritage, the Honourable Carmel Sepuloni committed to supporting New Zealand museums in the repatriation of all human remains held in their collections. This work is being undertaken in cooperation with the museums involved in the repatriation network. For us this is an exciting time.

As a result of our relationship building with international institutions and, more importantly, with our own museums nationally, we are finally working more cooperatively to begin to make right the wrongs of the past. Though in these discussions we tend to focus mainly on the colonial powers of the time, such as England in the case of Aotearoa New Zealand, we must also deal with our own colonial past.

Our museums are still one of the most poignant symbols of that colonial past and therefore we must ensure that meaningful relationships, collaborations, and new forms of cooperation are developed and maintained. Research, repatriations, and exhibitions which provide a space for communities to tell their own stories on their own terms are some of the ways in which museology in Aotearoa New Zealand is changing. Museums can no longer be the colonial big brother for all things cultural, it is time to step aside and enable the objects and ancestors to talk through their own people with our support. This I believe makes for a better and more meaningful museology.

Dr. Amber Aranui (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) is project lead for Ngākahu – National Repatriation Project, which supports New Zealand museums and iwi in the return of ancestral remains held in museums collections. She is the chair of the New Zealand Repatriation Research Network, set up to assist repatriation researchers to work collaboratively with the aim of proactively returning ancestral remains back to iwi, hapū and other communities around the world.

Amber has been the researcher for the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme for over 11 years, and has developed an interest in the research, collection and trade of human remains and the effects on indigenous peoples throughout the world.

References

Cheeseman, T. 1885. Letter Frm Cheeseman to Prof Flower, 25 May 1885. Auckland War Memorial Museum Archives, MA96/6, Letter Book 1882-1890, 285.

Colonial Museum, 1866. Colonial Museum Receipt Book 1866-1904. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Archives: MU000126.

Echo-Hawk, W. R., 1998. Testimony of Walter R. Echo-Hawk before the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs on a Substitute Bill (Amendment No.2124) for S.187, the ‘Native American Museum Claims Commission Act‘, 29th July.

Meinertzhagen, F. H., 1879. Letter from F. H Meinertzhagen to J. von Haast, dated 17th November 1879. MS Haast Family Papers. Correspondence: Maskell-Middleton. Folder 119: J H Meinertzhagen 1875-1879. MS-Copy-Micro-0717-09, Folder 119. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Reischek, A., 1952. Yesterdays in Maoriland. Translated and edited by H. E. L. Priday. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.