“How Can your Research Benefit our Community?”

How a Multilingual Research Dissemination Booklet Emerged

“How do I benefit from your research?” I often heard this question before or after conducting interviews with my research participants. Each time someone confronted me with this question, I felt a sense of discomfort, unable to promise anything concrete. I soon began engaging in dialogue with participants about what their expectations and motivations were and what I could offer. The residents in rural areas of northern Botswana face many pressing issues such as limited access to water, food, and healthcare as well as unemployment, and dangers posed by wildlife. A common hope was that these problems could be addressed by outsiders like me. While immediate solutions are difficult to offer, the least I could provide was sharing my research findings with people. Nevertheless, I wondered how my research could be useful for the local communities. How could I best communicate my research findings back to the people I worked with? Which ethical obligations and responsibilities did I have as a researcher working with marginalized individuals? These questions accompanied me throughout the research process and initiated the idea to work on a multilingual booklet for our research participants together with my research assistants Tshwarelo Sauqho and Onalenna Monnaaleso. In this blog post, I write about some of our reflections and the process of creating the booklet.

My PhD project deals with changing human-cattle-lion coexistence in the eastern panhandle of the Okavango Delta in Botswana. The background to my research topic is the growing global presence of human-wildlife conflicts and the need to understand and address them in a world of increasing biodiversity loss and environmental injustices. In recent years, “coexistence” has become a popular buzzword and concept in conservation approaches dealing with human-wildlife conflict, shifting the focus more towards the positive aspects of human-wildlife relations. Nevertheless, it often remains unclear what coexistence means for different people (Knox et al. 2021) and whether the concept has contributed to changes in conservation (Fiasco and Massarella 2022). In my research, I try to deal with these questions through an ethnographic case study. I spent over a year accompanying the work of the lion conservation NGO “CLAWS Botswana” and local agro-pastoral farmers to gain an understanding of what it means for people and lions to share a landscape, how their interactions with each other have changed over the years ,and how recent conservation work is impacting their lives. Before my research, I agreed with CLAWS on possible research topics that were of interest to the work of the organization. CLAWS also acted as a gate opener for research contacts in the local communities. However, I was not able to contact local people prior to my arrival in the eastern panhandle in November 2022. Looking back, I would have liked to include interests from the communities in my research planning from the start through, for example, conducting collaborative workshops and meetings. This limitation meant that my research already had a certain direction in advance, but I tried to adapt it flexibly to the interests of my participants. At the time of my PhD proposal writing, I was not very aware of collaborative research methods and I was additionally under time pressure to start my data collection soon. However, I also recognize that this might be considered a structural academic problem; funding schemes often do not provide enough time and budget for developing collaborative research with non-academic partners. Engaging in a dialogue on common research interests, priorities, and building reciprocal relationships takes time, trust, and direct engagements. It is often difficult to plan those important personal encounters from a distance. Beyond this, my impression and that of some of my students is that anthropological teaching still lacks a wider inclusion of participatory and collaborative research approaches. On the other hand, retaining a certain degree of autonomy as a researcher to shape the research process contributes to academic freedom and constructive generation of knowledge.

My research is part of a larger ERC-funded research project that seeks to understand the impacts of large-scale conservation on humans and wildlife in the biggest land conservation area, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA). Hence, my PhD focus and the way I conducted my research was, to a certain extent, determined by my affiliation to the project and the funding scheme of the European Research Council. While my topic was roughly predetermined through the project, I was still free to decide how I would shape it in detail in addition to where and with whom I would work. In the following, I explain how I came to choose my research site and participants.

Marginalization Behind an “Untouched Wilderness”

To understand the postcolonial setting in which I conducted my PhD fieldwork, an introduction to its local power and racial dynamics is necessary. The Okavango Delta, framed as a scenic and untouched wilderness area by tourism operators, hosts a rich diversity of (threatened) wildlife populations and ecosystems. This attracts numerous international tourists each year who mainly come from the so-called Global North. Since Botswana pursues a high-cost-low-volume tourism strategy (Mbaiwa 2003), most of the tourists are accommodated in luxurious safari camps away from villages. The camps are still often run by white foreigners and locals can rarely afford to stay there. Although the number of local guides and tourism managers seems to have increased in recent years, many of the local people continue to experience safari tourism from behind the scenes, cleaning for and serving tourists in low-paid positions.

During my research, I learned that from the 1970s to the early 2000s, many people were urged to relocate away from the northern delta with promises of development and better access to social services to make room for expanding wildlife tourism and conservation. In the process, their access to natural resources was also considerably restricted. Local ideas about whiteness are therefore tied to power, money, and (ownership of) wildlife, ideas that I was constantly confronted with during my research. However, these are not just ideas, but also real inequalities that do exist.

Even though tourism is an important source of regional employment, local inhabitants pay a price for the flourishing wildlife populations. They have to coexist with them on the fringes of the delta, and field crops eaten and trampled by elephants and cattle killed by predators are part of this “uneasy” coexistence. In addition, occasionally fatal incidents between people and wildlife happen and the fear of getting attacked is a constant concern for many people. In northern Botswana, communal areas are mostly located in the vicinity of wildlife management areas. Although there is some veterinary fencing around these wildlife management areas to separate domestic animals from wildlife, much of this fencing is damaged and permeable to wildlife such that wild animals also roam through communal areas. Freedom of movement is also crucial for the connectivity and long-term survival of wildlife populations.

Although many conservation NGOs, the state, and researchers are trying to mitigate human-wildlife conflict, it is still a significant hurdle alongside further social and environmental challenges such as unemployment or droughts and diseases. Botswana is often titled the “African Switzerland:” the country’s economy has made major steps since the 1980s mainly thanks to its diamond mines in the Southern and Central Districts. However, income distribution in the country is very unequal (World Bank 2015) and particularly the North remains behind. In the northern Ngamiland District, where I conducted my fieldwork, more than 60% of people live in poverty in contrast to 20.84% overall poverty in the country (Poverty Eradication et al. 2021). Although national social support and poverty eradication programmes exist, many people in my research location felt left behind by the state and hoped that researchers could improve their situation.

Research Fatigue in Botswana: Tensions between Basic and Applied science

The distinction between basic and applied research is a fundamental concept in the philosophy of science. Basic research aims to gain general knowledge and theories on a topic while applied science aims to solve specific problems and serve practical needs. Yet, both sciences are interconnected and build upon each other. Problems can only be addressed with appropriate fundamental knowledge about a situation or phenomena. Basic research can also be ainformed by its future use and applicability (Stokes 1997) which usually have to be addressed in research proposals and funding applications. Therefore, there is no strict dichotomy between the two sciences. In northern Botswana, however, I encountered a kind of opposition between basic and applied research. This might stem from a possible imbalance between the amount of basic and applied research being carried out, with basic science outweighing applied.

Besides tourists, the wildlife haven in northern Botswana has attracted many international researchers in the past decades, especially biologists (LaRocco et al. 2020). Like in tourism, inequalities are also evident in knowledge production, as most of these researchers are white and come from the Global North. An increasing academic interest in human aspects of conservation has prompted more research involving rural communities that live alongside wildlife.

Before I started my ethnographic fieldwork in October 2022, I visited northern Botswana together with my project colleagues for an initial exploratory trip in March 2022. The trip aimed to identify potential future research topics and locations as well as to establish local contacts. Besides local community representatives, we met different NGO members working on human-wildlife conflict and community-based conservation. Many of those NGO members in leading positions are white foreigners who arrived as researchers in the country and established applied programs after their studies. During these meetings, research fatigue was frequently mentioned. We were told that many researchers had already come to Botswana and left without providing feedback to their research participants while the problems on the ground remained unchanged. Disappointed by such experiences, some of the NGO staff warned that people in the villages were no longer willing to participate in further research. They argued that research in the area should be applied to serve the needs and problems of people on the ground instead of just addressing broader questions of global concern in the name of basic research. In an interview (1.12.2022), one NGO member commented (1.12.2022): “What has faded away is the luxury of being able to ask questions because it’s interesting to know the answers.”

Apart from Botswana, research fatigue is a growing global concern for researchers and their participants and might threaten future research and trust in academia and science (Clark 2008). Addressing its causes and impacts is therefore of great importance for research ethics and good scientific practice. Learning about research fatigue was an important experience in my research planning so as not to continue the chain of fatigue. I decided to conduct my research mainly in one place that had not yet been “over-researched” so that I would not repeat questions and topics and would be able to build long-term relationships with people.

The larger research project that I am part of is not concerned with solving problems at the local level. Rather, it is about generating knowledge for the advancement of concepts and debates in environmental anthropology (in short: basic science). Following this approach, the project also works together with scientists and institutions in southern Africa and funds some of them. In the longer term, the project’s research might lead to an improvement in conservation, ideally to greater fairness and involvement of local populations through communicating findings to governments, conservation actors, and wider society.

Anthropology, as a primarily basic science, is particularly good at making local voices and perspectives visible and revealing inequalities. But no change on the ground is guaranteed soon. For many of my research participants, however, only the present mattered and not a distant future. Therefore, I found myself facing tension between doing basic research and having the desire to provide fast, tangible benefits with my work. Especially in marginalized contexts, ethical obligations and responsibilities for researchers (from privileged positionalities) should be critically addressed. For example, researchers can use their privilege, power, and knowledge to support marginalized people beyond the research. For me, this meant supporting my participants and other villagers with everyday tasks, such as writing letters, applying for jobs, finding out any information about bureaucratic issues, and giving them lifts. While my research did not contribute to immediate benefits, I tried to make my stay helpful in many ways in exchange for the trust and time people allowed me.

Exploring Various Ways of Creating Reciprocity

Research fatigue was not as big of an obstacle as I had feared. I was welcomed by most people and I formed many meaningful relationships in the eastern panhandle, some of which continue to this day. However, the question of what I could give back to people with my research in return for the time, information, and trust they gave me was a constant concern throughout my research process. This was a concern that frustrated me at times as I did not have clear answers and often felt left alone with this question. During the years of my PhD, I got a general feeling that a great part of the academic business is concerned with publications and researchers’ visibility and not so much about what tangible contribution we make in a world faced with multiple ecological and social crises. Of course, the precarious structures in academia together with limited time and funding also mean that focussing on one’s own career is important to stay in the race and not become unemployed. At the same time, there is a growing interest in collaborative research and knowledge co-production in academia which may open up new avenues and agencies.

To bring some action to my ethical doubts, I decided to make sure to disseminate my research findings in an understandable way to my participants. In collaboration with my research assistants, Tshwarelo and Onalenna, a multilingual illustrated booklet emerged. During my first Kgotla meeting,[1] I asked the community for permission to stay in the village and conduct research and some (literate) people expressed the idea for a book about their history and area. I intended to transmit our gathered research data back to people and contribute to the documentation of local history, knowledge and debates for future generations. Learning about the past delta resettlements and restriction of resource rights, I realized that there are unsolved issues that contribute to human-wildlife conflict and that a book could ultimately lead to discussions about environmental justice by displaying different voices and opinions. Some people were curious about the idea of a book in which they could read some of their local stories and that they could pass on to their children. However, for others, a book was not enough; instead, they hoped for material aid, such as boreholes, or that I would create my own company and employ people. Previously, a few ecologists had come to the eastern panhandle and subsequently founded conservation NGOs, creating jobs. This created the idea that applied work and jobs would follow research and hence a similar expectation weighed on me.

Working on the Booklet: Collaboration via WhatsApp

Working on the booklet with my assistants was extremely time-consuming. Neither of them has a computer, so I sent them audio snippets and texts to transcribe and translate via WhatsApp over several months. Beyond that, I consulted them for their opinion on the contents of the booklet. This required a lot of patience and effort from all of us. Even though I tried to work on the book as collaboratively as possible with my assistants, I did not get as much input from them as I initially would have liked. The distance between us certainly played a role in this because we were not able to frequently gather to discuss the contents of the booklet.

Upon further reflection, however, I realized that our differing positionalities and the related inequalities also impacted our collaboration. Both of my assistants have to deal with more important issues in their everyday lives, such as getting enough food, taking care of sick family members and children, and getting along financially while I have a relatively comfortable life in an employed PhD position that allows me to put such effort into the book. Working with me was only a temporary job on the side for my assistants. Due to my restricted research time and funding, I could never offer them a long-term job perspective. Beyond this, they did not have the same educational possibilities as me and therefore have less access and interest in research. Differences in power also played a role in that, as a boss and academic, I was probably perceived as having more authority and experience in conducting formal work of this nature.

Their restraint is therefore understandable and our collaboration could not be symmetrical against this background. Yet, they are the co-authors of the booklet, because this booklet would never have been realised without their work. They put me in touch with research participants, acted as important mediators, and often took the lead in interviews. They participated in the selection of the book’s content and transcribed and translated a great part of it. They were always there to give me advice on what content might be (in)appropriate, which photos we could use, and how we should design the entire booklet. They also got to know their communities anew through the research, and learned particularly about local history. Tshwarelo commented:

I was happy to work with Julia on the research because I learned a lot of things that I didn’t know from the old days like hearing many stories about how our different tribes lived together. There were some few challenges because we met people who were struggling to understand what we were doing even when we told them what we were doing.

In the last sentence, Tshwarelo refers to the difficulty of communicating to people what (basic) research is. This is, again, related to the initial question of what benefits people get from research. For some people, the purpose of collecting information for the sake of rather abstract knowledge to promote debates and improve conservation at large was not relevant in comparison to more urgent daily needs, such as getting enough water and food. Others, however, spoke enthusiastically in interviews and were happy to have their attitudes and knowledge documented. Whether and how research is perceived as useful by people therefore varies in line with heterogenous interests in communities. Even though we repeatedly tried to explain what basic research is about, it remained difficult to cultivate a broader understanding of it in an environment where many people have no access to formal education and science.

First Dissemination Visit

In August 2024, I revisited the eastern panhandle for three weeks. Originally, I had hoped to have finished the book by then and come back with it to the villages. However, our progress in the production of the book was delayed. As the booklet was not yet completed, I created three illustrated information sheets depicting some of the research contents that I laminated and distributed to my research participants. We organized a meeting in each research location to which we invited participants and for which we cooked food. Before eating together, Tshwarelo and Onalenna read out the information sheets since some people couldn’t read and then there was timefor feedback and questions. During the meetings, I had the impression that most people were happy about my return and getting a first update on my research process. Nevertheless, some of them reminded me of my bigger task, that I still had to bring the book to them.

During one of the meetings, however, my role as a researcher was also debated: Some people demanded the return of their former lands in the delta which they had left several decades ago. A great part of my research focused on those resettlements, why they had taken place, and how they changed local human-wildlife interactions. Although people resettled of their own will in different phases between the 1970s and early 2000s, most of them faced indirect pressures by the government and tourism and conservation actors who aimed to transform their land into conservation and wildlife areas. Motivated by promises of development and access to facilities, people resettled to the villages along the eastern panhandle road where they live today. Many of them had never returned to their ancestral lands and looked back to their past lives with nostalgia. Some felt that they had been wronged by the forced resettlement of their land, from which they no longer benefit. Hence, some participants expected me to support them in reclaiming this land to resettle or on which to build their own safari camps to generate income. My assistants supported me in this matter, mediating and mitigating expectations placed on me as an individual researcher to obtain land titles for people. However, the meetings helped formerly resettled people to connect with each other and jointly discuss their past and future visions. In the longer term, I also hope to use my research findings to contribute to a dialogue on environmental justice between the private sector, conservation actors, the state, and the local population.

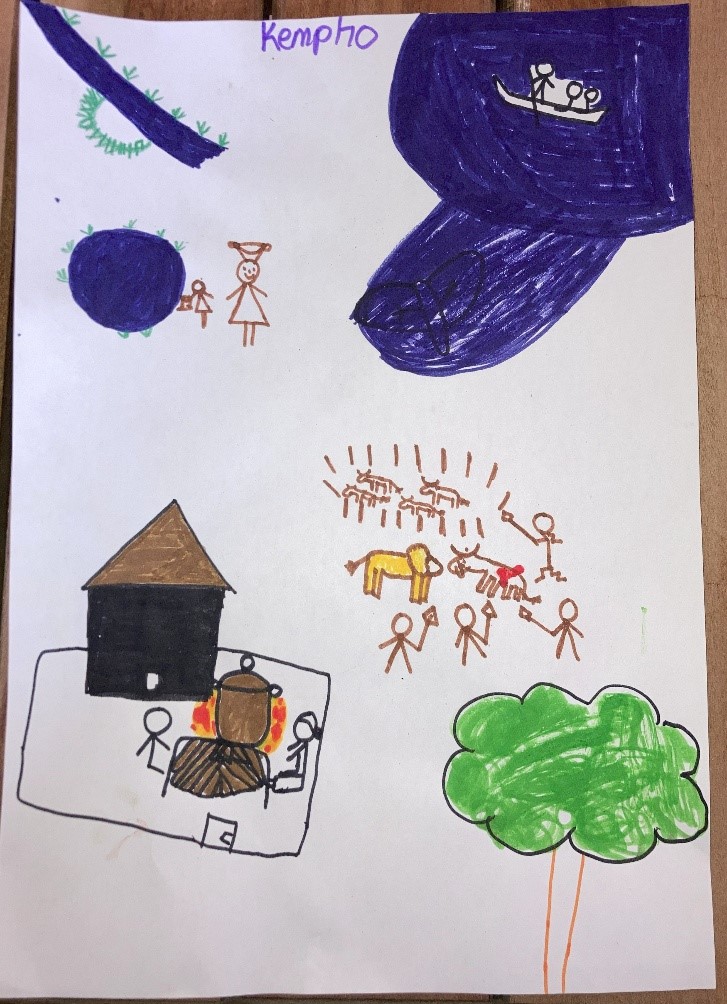

During my research time, I also had many encounters and relationships with children. To give them a better understanding of my research, I organized a creative workshop at the local primary school in Gunotsoga, a village in the area, on the history of the resettlement from the delta. The workshop included an explanatory section; a dialogue between Tshwarelo, me, and the children; and a creative painting exercise in which the children reflected on coexistence with wildlife. When I met some of them again this year during my visit, they remembered what they had learned in our workshop. Although many children fear wildlife, they still show interest in conservation, perhaps influenced by recent environmental education efforts at schools.

Coming Back with the Finished Booklet

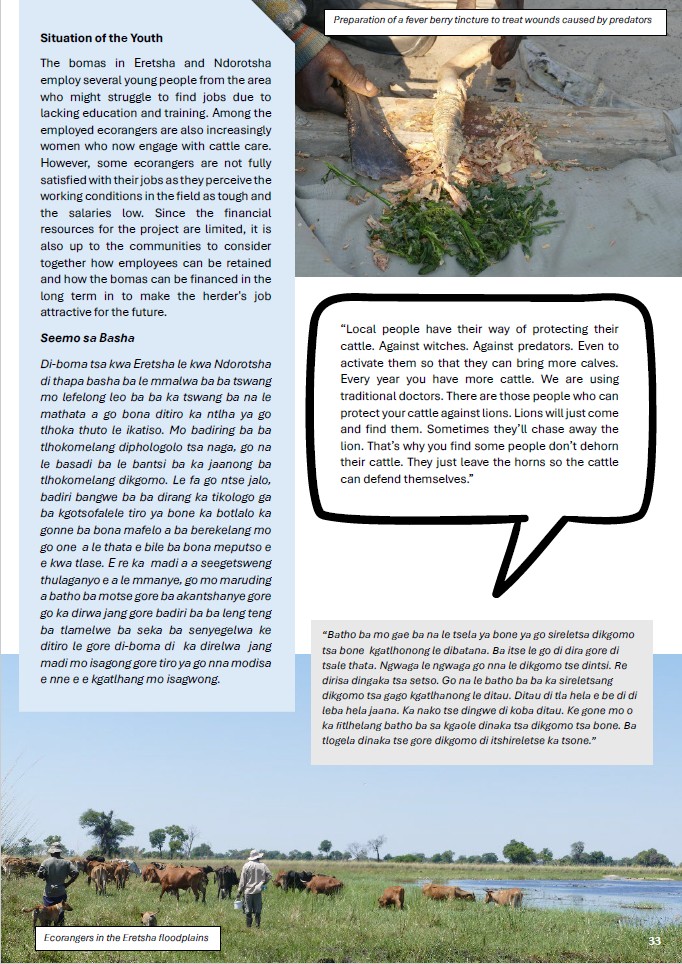

In March 2025, I finally came back with the finished booklet titled “Tshidisano” (Setswana for coexistence, living with each other). The booklet gathers different voices from the community and CLAWS in speech bubbles, short explanatory texts, open questions, and photos/graphics relating to the different topics. The book covers various historical and current events in the eastern panhandle related to resettlement and changing human-wildlife coexistence and land governance. These include, for example, how local residents scavenged from lion killings in the past to quickly obtain meat, how they experienced the tsetse fly infestation in the delta, and the emergence of tourism and modern technology-orientated wildlife conservation. While the content in the speech bubbles is not attributed to names, some photos and names of all participants are listed at the beginning of the booklet. Unfortunately, one of my assistants was in poor health at the time of my visit, so I took the distribution of the books mainly into my own hands without a big meeting. I visited specific people and met others by chance on paths. I left the books for the research participants I did not meet with at my assistants’ homes so that they could pick them up there. In the end, however, these individual meetings proved to be particularly useful for having closer interactions with people about the booklet. Photos of people and places in the booklet aroused the most curiosity; seeing themselves, friends, relatives, and familiar places in a book seemed to make many people happy. This showed me the importance of visual language for communicating research content. A research colleague from Botswana also commented on the book: “It’s good that it doesn’t have much text.” Moreover, not all research participants are literate and therefore have limited access to the contents of the booklet. I visited one illiterate participant at his home and read parts of the booklet to him. I hope that his grandchildren will continue reading to him and thereby engage in an intergenerational dialogue about local history and politics. In addition, some people were surprised to read Sembukushu, their mother tongue, in written form. Unlike in Namibia, where some local schools teach Sembukushu, the language is mainly used orally in Botswana and increasingly mixed with Setswana words. Some participants expressed that they had learned new things about the resettlement history of their area that they had not known before. One participant commented that he feels the book would be a kind of lexicon for his area where all topics could be looked up.

As stated in many ethical guidelines and codes, research dissemination should be an ethical responsibility for researchers, especially when working with people who have been neglected by the state and whose basic needs are not met. In such challenging contexts, participants often associate research with great hope for improvement. This hope should be engaged with transparently by researchers. In addition, shaping research in collaborative ways and using one’s own privileges and knowledge for the benefit of research participants can be part of ethical responsibilities. Even though I have written this blog post as a single author, “Tshidisano” is a collaborative research dissemination effort based on the stories and perspectives of different knowledge holders in the eastern panhandle. It has been an extended collaboration beyond the research work between my research assistants—Tshwarelo and Onalenna—and me. Although research participants did not actively shape the book production process, the idea of the book was discussed throughout my stay in the eastern panhandle and research participants had opportunities to provide feedback. As I described in the blog post, due to our differing positionalities and social workloads, this collaboration was not ideally symmetrical since I maintained the lead role in the book’s production. However, it was an attempt to collaborate on eye level as far as possible and to break the chain of research fatigue. Having created and distributed the book, looking into happy faces and hearing some first appreciative feedback feels like having produced a small tangible benefit for my research participants. Yet, I continue to reflect about further locally relevant impacts that my PhD research can contribute to while working on my dissertation.

I encourage other PhDs and researchers to look for collaborative and understandable ways of disseminating their research. Depending on the interests and backgrounds of collaborators, this can take multimodal and experimental forms such as films, photography, reports, podcasts. It is best to already think about this with participants and collaborators during the research process. If necessary, different dissemination formats must be created for and with different audiences to fulfill different interests and uses. In practice, unfortunately, there is often a lack of budget and time to devote to collaborative research and dissemination, so it often only remains a side project. Institutions and funding bodies should therefore better integrate non-academic collaboration and transfer-oriented work into their structures, funding schemes, and teaching. The focus should not be so much on “publish or perish” in peer-reviewed journals (Mosher 2013), but rather on the collaborative development and transfer of knowledge. While I do not think it is possible to foresee and communicate the benefits of research in early stages, I believe it is important to stay in constant dialogue with research participants about expectations, motivations, and feasibility.

Note: An earlier and shorter version of this blog article can be found on the Rewilding blog: https://rewilding.de/dealing-with-research-fatigue/

Bibliography

Clark, T. 2008. “’We’re Over-Researched Here!’: Exploring Accounts of Research Fatigue within Qualitative Research Engagements.” Sociology 42 (5): 953-970. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094573.

Stokes, D. E. 1997. Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Brookings Institution Press.

Fiasco, V., and Massarella, K. 2022. “Human-Wildlife Coexistence: Business as Usual Conservation or an Opportunity for Transformative Change?” Conservation and Society 20 (2): 167-178. https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_26_21.

Knox, J., K. Ruppert, B. Frank, C. C. Sponarski, and J. A, Glikman. 2021. “Usage, Definition, and Measurement of Coexistence, Tolerance and Acceptance in Wildlife Conservation Research in Africa.” Ambio: A Journal of Environment and Society 50 (2): 301-313. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s13280-020-01352-6.

LaRocco, A. A., J. Shinn, and K. Madise. 2019. “Reflections on Positionalities in Social Science Fieldwork in Northern Botswana: A Call for Decolonizing Research.” Politics and Gender, 16 (3): 845–873. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000059.

Mbaiwa, Joseph E. 2003. “The Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of Tourism. Development on the Okavango Delta, North-Western Botswana.” Journal of Arid Environments 54 (2): 447–467.

Mosher, H. 2013. “A Question of Quality: The Art/Science of Doing Collaborative Public Ethnography.” Qualitative Research 13 (4): 428-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113488131.

Poverty Eradication, Statistics Botswana, and United Nations Development Program. 2021. Pilot National Multidimensional Poverty Index: Report 2021. Republic of Botswana, Office of the President. https://www.statsbots.org.bw/sites/default/files/Pilot%20National%20Multidimensional%20Poverty%20Index%20Report%202021.pdf.

World Bank 2015. “Gini index – Botswana.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=BW

[1] Kgotla is the communal space of villages in Botswana where the community gathers and discusses local affairs. It also has the function of a local court where fines for offences are negotiated.

Julia Brekl has a research interest in human-environment interactions, Indigenous and local knowledge systems, multispecies ethnography, and research ethics. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Regional Studies of Latin America – Social Sciences from the University of Cologne, Germany and the National University of Colombia, Bogotá and a master’s degree in Social and Cultural Anthropology also from the University of Cologne. Since February 2022, she has been working on her PhD project within the ERC Rewilding the Anthropocene project at the University of Cologne. Before academia, Julia was engaged in journalism and international cooperation. The transfer of research into the wider society is therefore a particular interest for her.