Decolonizing Provenance Research in Practice. Some Guidelines

DCNtR Debate #2. Thinking About the Archive & Provenance Research

With increased public and professional calls to re-examine collecting, many museums have renewed commitments to provenance research. Provenance research raises pressing ethical questions: to whom should cultural heritage belong? How can museums equitably address unethical historical collecting practices? Provenance cannot necessarily answer these questions but sharing provenance information allows museums to tell more nuanced stories about their roles in global history. At best, provenance research can identify stakeholders or descendants with whom museums can more meaningfully engage collections. At worst, provenance research can be used to legitimize museum interests over those of stakeholders and defer addressing collection ethics concerns. Provenance researchers therefore play vital roles in “the long hard work of decoloniz[ing]” museum practices.[1]

That museums have historically leveraged institutional power and relied on unethical means to amass collections is undisputed. [2] Museums’ quotidian documentation practices are just as subject to legacies of power and privilege. However, museums rarely acknowledge these histories because they exist as methods of documentation rather than through them. Researchers failing to critically analyze the power encoded within these mundane structures risk replicating them.

Unfortunately, little practical guidance exists for researching provenance in ways that examine institutional biases, include diverse perspectives, acknowledge limitations, and remain accessible to many audiences. This paper suggests strategies for conducting provenance research against the grain of power and privilege. Drawing from experience as a provenance researcher who focuses on collections acquired during colonial contexts, I suggest some ways to make provenance research processes and products more inclusive, transparent, and accessible. I advocate that through such research, museums can more honestly illuminate their collection histories in ways that are more meaningful to all stakeholders.

Every object has a unique trajectory from maker to museum. Understanding that trajectory requires researching not just the facts of an object’s history of ownership, but also the social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of the period(s), place(s), person(s), and law(s) affecting that history. Provenance researchers rely as much on primary sources like inscriptions, receipts, and personal memories as on secondary sources like historical (oral or written), anthropological, or legal scholarship. Although resources and strategies vary from object to object, common principles underpin all provenance research.

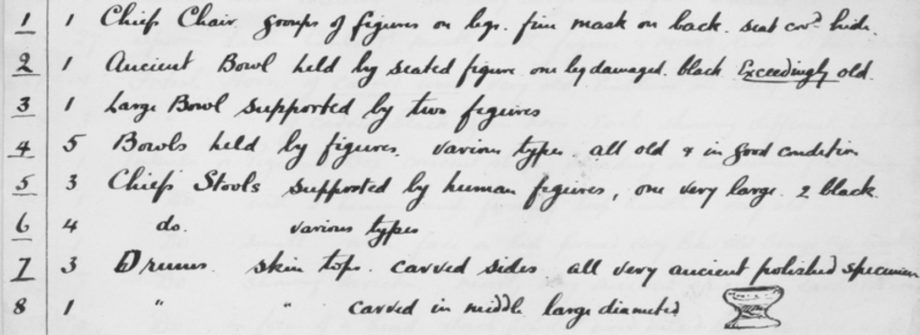

Before analyzing a source’s content, researchers should critically examine its structure. As Povinelli argues, institutions like archives often “shelter the memory of [their] own construction so as to appear as a form of rule without a command.”[3] The format of accession ledgers, receipt books, and databases determine what information museums preserve and omit. For example, accession ledgers often include cultural attributions, but rarely identify the attributions’ sources. Receipts often record vendor or donor names, but rarely acknowledge their authority to transfer the object. Provenance researchers must therefore examine what seemingly mundane collection documents include as well as what they omit, overlook, or assume.

Letter from William O. Oldman to Stewart Culin, January 13, 1922. (General correspondence S01.04.01.007), Culin, Stewart, Curator of Ethnology, 1903-1929. Culin Archival Collection. Brooklyn Museum Archives.“

A provenance researcher’s due diligence also requires evaluating sources’ trustworthiness. Researchers must read between the lines of documentation mindful of potential biases given a source’s time, place, and circumstance. The CRAAP test (Currency, Relevancy, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose)[4] provides one method for interrogating sources’ subjectivity. Addressing “currency” requires examining how contemporaneously a source relates to the object and how biases might have affected its documentation. Considering “relevancy” entails inquiring who the source’s intended audience was. Examining “authority” involves asking upon whose authority the source relies and whose perspectives might be missing. Considering “accuracy” demands examining what kinds of evidence supports the information and whether it is verifiable elsewhere. Finally, examining “purpose” entails asking why the information exists and, given its intended audience, what it might assume or leave unaddressed.

Historically, the provenance field has assumed individual ownership of inanimate objects. However, this overlooks communities who collectively keep objects, animate materials, or objects that instantiate divinity. Because provenance research has historically relied on tangible or written documentation, researchers often unwittingly overlook histories recorded orally. At minimum, provenance researchers should treat oral and embodied histories equally to published and tangible sources. Wherever applicable, researchers should also strive to include diverse means of recording history in their research.

Provenance researchers should try to corroborate documentation from multiple sources, particularly for works possibly acquired during colonial contexts, war, conflict, or socio-economic upheaval. Unfortunately, this is not always possible. Researchers must therefore rely on the expertise of others more familiar with the specific time periods, places, or circumstances at issue. Wherever possible, researchers should therefore strive to collaborate with communities of origin and/or makers’ descendants to include diverse perspectives on history.

Provenance researchers must also pay attention to how they document their research. Provenance research inevitably uncovers stories whose details are unverifiable. Rather than omit uncertainty from their records, researchers should acknowledge what they know, what they do not know, and their level of certainty regarding the information. This sometimes means admitting that provenance information does not exist or that research is ongoing. Personally, I rely on “reportedly,” “possibly,” and “probably” for increasing levels of certainty regarding information. Such transparency particularly ensures that future researchers understand the limitations or uncertainties regarding an object’s provenance.

Finally, provenance researchers should strive to make their research accessible to scholarly and lay audiences alike. Traditionally, provenance documentation relies on typographical shorthand involving particular meanings of semicolons, periods, and parentheses. Even provenance experts find such statements difficult to read. Provenance researchers wishing to make their research accessible should therefore strive to format information narratively. Rather than denoting gaps between owners with a period, a provenance statement can narratively acknowledge gaps such as “between 1900 and 1930, provenance not yet documented.” This ensures that audiences who may not be familiar with provenance nomenclature do not misinterpret misinformation.

Museum professionals advocating for responsive, anticolonial practices have likely observed how easily their projects can become subsumed into the very logics of institutional power and univocality against which they work. Provenance research is not immune to this phenomenon. Resisting this propensity while modeling inclusive, transparent, and equitable practices remains one of the most challenging aspects of decolonizing museum work in practice. But committing to such practices ensures that provenance research remains inclusive, transparent, accessible, and meaningful for current and future audiences, staff, and stakeholders.

Meghan Bill is Coordinator of Provenance Research at the Brooklyn Museum. As the Museum’s primary provenance researcher, she investigates collection histories and works to make provenance research and documentation practices more equitable and transparent. Her research interests include colonial-era provenance research, legal issues of cultural heritage management, and Pacific maritime and colonial histories. She has an M.A. in Museum Anthropology from Columbia University and is a J.D. candidate at Fordham University School of Law.

Footnotes

[1] Merritt 2019.

[2] See, for example, Jacknis 1988; Classen and Howes, 2006; Sleeper-Smith 2009; Peers 2017; Hicks 2020; Kreps 2020.

[3] Povinelli 2001, 151.

[4] Blakeslee 2010.

References

Blakeslee, Sarah. 2010. “Evaluating Information – Applying the CRAAP Test.” Meriam Library, California State University, Chico, 2010. Accessed March 28, 2022.https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf.

Classen, Constance and David Howes. 2006. “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts.” In Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth B. Philips, 199-222. Oxford and New York: Berg.

Hicks, Dan. 2020. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution. London: Pluto Press.

Jacknis, Ira. 1988. “Franz Boas and Exhibits: On the Limitations of the Museum Method of Anthropology.” In Objects and Others: Essays on Museums and Material Culture, edited by George W. Stocking Jr., 75-111. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Kreps, Christina F. 2020. Museums and Anthropology in the Age of Engagement. New York and London: Routledge

Merritt, Elizabeth. 2019. “TrendsWatch 2019 Executive Summary.” American Alliance of Museums website, March 19. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.aam-us.org/2019/03/19/trendswatch-2019-executive-summary/

Peers, Laura. 2017. “The magic of bureaucracy: repatriation as ceremony.” In Museum Worlds 5(1): 9–21.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. 2011. “The Woman on the Other Side of the Wall: Archiving the Otherwise in Postcolonial Digital Archives.” In A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 22(1): 146-171.

Sleeper-Smith, Susan. 2009. Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.