The Fundamental Problem of Ethnography and Colonialism

Some thoughts on two exhibitions in Berlin’s House of World Cultures

Through 6 January 2020 in the House of World Cultures in Berlin, one can still visit two exhibitions that have several things in common. The first is not unusual, but rather everyday museum practice. Both exhibitions are devoted to the work of dead, white, German men. “Spectral White: The Appearance of Colonial-Era Europeans” deals with a collection of figures owned by the ethnologist and former Director of the Rautenstrauch Joest Museum in Cologne, Julius Lips. “Love and Ethnology: The Colonial Dialectic of Sensitivity (after Hubert Fichte)” shows works by this writer and ethnographer.

Picture 1: View of the exhibition “Spectral White: The Appearance of Colonial-Era Europeans”. Copyright Silke Briel/HKW.

Somewhat more unusual is the second thing the two exhibition concepts have in common: they are devoted to unconventional and resistant dead, white, German men.

Julius Lips (1895-1950) was a Social Democrat in the Weimar Republic and held the office of Director of the Cologne Ethnological Museum when the National Socialists took power in 1933. Removed from his office by the Nazis, he and his wife went into explicitly political exile in the United States. There, through the mediation of Franz Boas, a central figure in US anthropology in his time and himself of German descent, Lips held a position Columbia University and later became a professor at Howard University, at the time the most renowned African-American private university in the United States. After the war, East Germany appointed him Professor for Ethnology and Comparative Legal Sociology at Leipzig University, where he died relatively young in 1950. Although some have criticized that Julius Lips’ wife made quite a hero out of him after his death,[1] his biography surely provides a positive reference point for a present-day democratic, anti-racist, and anti-fascist social and cultural anthropology.[2]

Picture 2: View of the exhibition: “Love and Ethnology: The Colonial Dialectic of Sensitivity (after Hubert Fichte)”. Copyright: Silke Briel / HKW.

Hubert Fichte (1935-1986) belonged to the postwar generation. As an extravagant, non-heterosexual artist and writer, he did not fit well in the conformist mainstream of Germany’s “economic miracle” era. He soon found himself in the burgeoning young artists’ scene of the Federal Republic and read his work in the Gruppe 47 in the early 1960s. In the ’70s, he began an absolutely exceptional work in the context of postwar Germany in which, on long foreign journeys to South America, the Caribbean, and Africa, he traced what he called the “gayification of the world”.[3] Like too many gay intellectuals, he died a victim of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, also relatively young.

The third thing the two exhibitions have in common, then, already leads us to where the matter becomes especially interesting. Both exhibitions are devoted to the work of nonconformist and resistant dead, white, German men who were interested in ethnography in the colonial world. With their ethnographic work and their views, they “developed a counter-position within the Western institutions”,[4] as the Foreword to the catalog of the exhibition “Love and Ethnology” says of Fichte, but which can also be said of both authors.

Picture 3: Fright figure/hentakoi in the form of an English colonial soldier, unknown artist, around 1900. Nicobar Islands, Indian Ocean, Rautenstrauch Joest Museum, purchased by J.F.G. Umlauff, RJM 23331. Copyright: Silke Briel/HKW.

Julius Lips’ book, “The Savage Hits Back”,[5] written in the 1930s in his US exile, poses the question “how the colonized saw the white ruling powers”.[6] Lips collected and studied ethnographic objects in which indigenous artists in the colonies depicted and represented the actors of colonialism. Lips thereby operated the shift in gaze as one of the central practices of ethnography. European presentations of the non-European in the stereotypical images of non-Western wildness and rawness clearly stand against a mirror-image correspondence outside of Europe. There, the Europeans are represented as grotesque, cruel wild men. The exhibition thereby presents many of the objects used in Lips’ book – partly from the collection Lips assembled, which is stored in the Rautenstrauch Joest Museum in Cologne. An example of this shift in gaze is a fright figure from the Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean that served Julius Lips as the title picture for the first edition of “The Savage Hits Back”. There, a British colonial officer with bared teeth raises his right hand in the air.[7] Reminiscent of the Hitler salute, it served Lips as an allusion to the political situation in Germany. This shift of gaze allows the viewer to initially take a (seemingly) other, non-Western perspective and can serve as a starting point for questioning the cultural construction that is usually experienced as one’s own and as normal.[8] In this sense, ethnography always contains a shift of gaze.

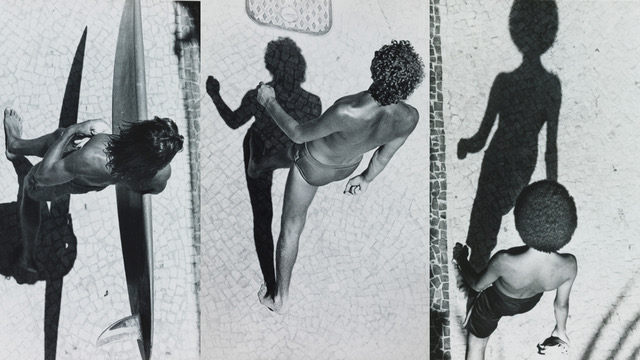

Picture 4: Alair Gomes, Photos from the series “The Course of the Sun”, 1975–1980. Copyright: Archives of the National Library Foundation, Brazil.

Fichte’s interest was equally ethnographic. He was enthusiastic about “the African culture”, which he thought formed a counterculture to the West in the Diaspora of the Caribbean and the Americas that made it possible to question “Western culture”. In his primary work, published posthumously as the 17-volume “Geschichte der Empfindsamkeit” (history of sensitivity), and in his works of “ethnopoetics”, Fichte thereby goes beyond the shift in gaze. His access to the Other, the non-European, proceeds in the mode of empathy. Through sensitivity and feeling, ethnography opens itself up to the Other, to awaken understanding and familiarity. Fichte definitely meant that sexually. In an interview with Monopol magazine, one of the curators of “Love and Ethnology”“, Diedrich Diederichsen, connected this mode of empathy with Fichte’s slogan of the “gayification of the world”.[9] Clandestine and like a network, like the gay world of the 1970s, the point is to experience the Other in feeling, to open oneself up to it, and to arrive at a different, new understanding. In this sense, empathy forms a central practice of ethnography, or, put another way: in this sense, ethnography is also gay practice.

But although both exhibitions are exhibitions about ethnography and use the ethnographic mode of knowledge, they both go beyond a plea for ethnography. Rather, they approach in a complex way the directly interlocked network of ethnography and colonialism. For both ethnographic practices, the shift in gaze and empathy, must fail, no matter how much they initially seem to succeed.

“Spectral White” shows this failure via the access to the ethnographic object. The curators Anna Brus and Anselm Franke impressively manage to show that the objects collected and described by Lips are in no way characterized by a simple shift in gaze, but by multiple ones. The biographies of the object show that they in no way represent “pure” indigenous reactions to colonial invaders, but were integrated in diverse ways in colonial power relations. Some were produced especially as souvenirs to be sold to Europeans. Others were regular commissioned works taking account of Europeans’ wishes as to how they should be depicted. Brus also made efforts to attribute some of the objects, which in Lips’ book are hardly historically contextualized, to individual artists and to gather information on them. This intense contextualization of the objects makes it possible to recognize them as the results of complex production conditions and power hierarchies. The colonial gaze remains inscribed in the objects; the shift in gaze into the non-European Other thus appears questionable, if not thwarted.

Picture 5: Coletivo Bonobando, Prata Jardim – Omindarewa, 2017. Performance by Implosão in the framework of the exhibition opening: Trans(relacion)ando Hubert Fichte. Copyright: Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia (MAM-BA), Salvador da Bahia.

“Love and Ethnology” likewise takes as its theme the failure of ethnography as the failure of empathy. Fichte, as already becomes clear in his work published in German, is initially interested in the Other as a provider of ideas. Even in terms of language, his work does not communicate with those with whom he empathizes. The starting point of the exhibition was therefore to translate Fichte’s work from German into Portuguese, for example, or into English to make it possible for local artists to grapple with it. These reactions to Fichte, mostly in the form of critical and broken appropriation of motifs, are then the subject of the exhibition curated by Anselm Franke and Dietrich Diederichsen. The exhibition reveals the degree to which the subjects/objects of Fichte’s ethnographic empathy and sensitivity feel misunderstood or at any rate differently understood. As Diederichsen elucidates, some criticize, for example, the fetish-like way in which Fichte refers to black bodies.[10] “Love and Ethnology” thus collects ethnographed people’s reactions to ethnography and thereby also demonstrates a colonial failure.

Fichte and Lips are primarily interested in Germany. The majority society of Germany was the target audience they wanted to productively confuse and to induce to think. What is colonial about ethnography is not solely that, as a research approach, it arose in times of colonialism and was institutionally connected with colonialism. In a certain way, ethnographic practice itself is ultimately colonial. The point is to understand, render visible, and represent under the conditions of European knowledge production and Western power apparatus. As constitutive as it is for the European understanding of science, the curious gaze that wants to accumulate knowledge about others and to save it and make it comprehensible is always a colonial gaze, in a sense.

This criticism of ethnography, which the exhibitions clearly take as their theme, could be redirected and applied to the exhibitions themselves, since they, too, somehow remain colonial ethnographic formats. Both have white (if still living) German curators who are interested in the Other, though with a more differentiated aim than their predecessors. Their target audience is a certain Western elite that goes to the House of World Cultures. “Love and Ethnology” commissions the production of art from the Global South, as if the latter were a producer of raw materials for postcolonial criticism at home. “Spectral White” ultimately remains in the mode of ethnic German self-enlightenment via what is foreign; the footnote is merely added that everything is much more complicated and entangled than previously thought. If one takes on this self-suggesting structure of argumentation, only one thing logically remains: the abolition of ethnography, complete with its museum variants. And not a few demand precisely that today.[11]

These points of criticism doubtless occurred to the curators, as well. Nonetheless, they chose not to abandon their exhibition idea, but to continue to pursue it. And this is precisely the attitude that also accepts social and cultural anthropology as a discipline: to put it disparagingly, that of a critical fellow traveller, or in a somewhat more friendly tone, that of a fellow-travelling critic. The paradoxical enterprise of ethnography is (and always was) to be aware of the constitutive colonial gesture that persistent thinking about others entails, to attempt to minimize the unequal power by a reflexive mode in accordance with one’s best knowledge (often with modest success), and finally to hold fast to the enterprise. Ethnography knows that, with the ethnographic gaze, which always has something colonial about it, understanding can be created that transcends social and cultural boundaries. But to acquire this knowledge about others is also always a gesture of power that can label what is understood in a hurtful way, if not worse.

To most, namely, the alternative appears the worse evil: an epistemic essentialism born out of colonial criticism in which everyone can only know something correctly about his or her “own people”, mixed with a scientific provincialism in which it is not only strenuous, but also morally questionable to look beyond the end of one’s own nose. The obvious problem with such a stance, however, is that it does even less to change colonial injustice, which continues to shape the world. What results is more the opposite of a decolonization of the sciences. It is no coincidence that epistemic nationalism and scientific provinciality are the basic building blocks of rightwing-nationalist politics. Rightly recognizing that scientific curiosity about how things may be elsewhere is a colonial gesture is one thing. Eschewing it entirely and nonetheless wanting to make a political statement against global inequalities cannot be done. Thus, for social and cultural anthropology, a modification of Churchill’s statement, equally well-known and unlovely: “Ethnography is the worst of all scientific approaches, with the exception of all the others.”

The two exhibitions “Spectral White” and “Love and Ethnology” dare to tackle this unpleasant task, and it is recognizable that, within them, a space for debate and negotiation is opening up in which it is worth thinking. Even if, like all ethnographic exhibitions, these are not free of colonialism, they can still promote a critique of colonialism – of course, at the price of losing any supposed moral purity. Ethnographic objects provide the space to speak critically about colonialism. Artists from the former colonies get a chance to speak about the colonialism of ethnography. The Western self-understanding is critically challenged. The entanglement of what is supposedly normal with colonial power relations comes into view. Spaces for questioning and criticizing the colonial world then open up that aren’t usually opened in exhibitions about dead, white, German men. It may be that the critical eye appears as a modest, often all too modest summary. Ethnography is used to that. And, as everyone knows, it may hope to make its difficult, more or less successful way to partial truths. Scientific perfection and solid sureness of standing on the right side of history are achieved only under different theoretical-methodological presuppositions. But without ethnography – and these exhibitions show this, too – it is difficult to mount a thoroughgoing critique of colonialism.

Jonas Bens is a Research Associate in the German Research Foundation’s special research area “Affective Societies” and teaches at the Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology at the Berlin Free University. His research emphases are in Political Anthropology and Legal Anthropology. He is currently working on a research project about the conflicts around ethnographic collections from the colonial era in Germany and Tanzania, seeking to understand more generally the transnational conflicts over property in the postcolonial world.

Translation by Mitch Cohen

Footnotes

[1] Fischer, Hans (1990): Völkerkunde im Nationalsozialismus: Aspekte der Anpassung, Affinität und Behauptung einer wissenschaftlichen Disziplin. Berlin: Reimer, p. 181-190.

[2] This becomes clear in Ingrid Kreide-Damani’s work in the history of science, in which she contrasts Lips’ life history with that of the faithful Nazi ethnologist Martin Heydrich: Kreide-Damani, Ingrid (2010) “Julius Lips, Martin Heydrich und die (Deutsche) Gesellschaft für Völkerkunde”, In: Kreide-Damani, Ingrid (ed.) Ethnologie im Nationalsozialismus: Julius Lips und die Geschichte der “Völkerkunde”. Wiesbaden: Reichert, p. 23-284. Kreide-Damani thereby amends the much more negative depiction of Lothar Pützstück, who recognizably negatively judged the decision of Julius and Eva Lips to return to Leipzig in communist East Germany, thereby shedding extremely unfavorable light on Lips’ biography: Pützstück, Lothar (1995) “Symphonie in Moll”: Julius Lips und die Kölner Völkerkunde, Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus. On this, cf. also the assessments of André Gingrich: Gingrich, André (2010) “Wege, Irrwege und Potenziale von Wissenschaftsgeschichte: Die ‘Causa Lips’ und ein Fach, das früher Völkerkunde hieß”, Kreide-Damani, Ingrid (ed.) Ethnologie im Nationalsozialismus: Julius Lips und die Geschichte der “Völkerkunde”. Wiesbaden: Reichert, p. 7-10.

[3] An interesting essay volume is devoted to this aspect of Fichte’s oeuvre: al-Daif, Rashid/Helfer, Joachim (2006) Die Verschwulung der Welt – Rede gegen Rede. Beirut – Berlin. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

[4] Wahjudi, Claudia (2019): “Wie die Kolonialisierten die weißen Machthaber sahen”. In Der Tagesspiegel of 14 Nov. 2019. Accessible online at https://www.tagesspiegel.de/kultur/ausstellung-im-hkw-wie-die-kolonialisierten-die-weissen-machthaber-sahen/25223592.html.

[5] In 1983, Julius Lips’ wife Eva published a German-language version titled “Der Weiße im Spiegel der Farbigen” (the white in the mirror of the colored) (Munich, Hanser).

[6] Diederichsen, Diedrich/Franke, Anselm (eds.) (2019): Liebe und Ethnologie: Die koloniale Dialektik der Empfindlichkeit (nach Hubert Fichte). Haus der Kulturen der Welt: Sternberg Press: 5.

[7] Cf. Wüllenkemper, Cornelius (2019) “Kolonisatoren im Portrait: Ausstellung Spektral-Weiß”. Deutschlandfunk. Accessible online at https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/ausstellung-spektral-weiss-kolonisatoren-im-portraet.691.de.html?dram:article_id=462424.

[8] Another very successful example of the ethnographic shift in gaze in the museum is the exhibition curated by Matthias Weiß “Wechselblicke – zwischen China und Europa 1669-1907” (shifting gazes – between China and Europe 1669-1907), shown from August 2017 to January 2018 in Berlin’s Kunstbibliothek (art library).

[9] Hindahl, Philipp (2019) Liebe und Ethnologie: “Wir wollen die Empfindungen restituieren”. In: Monopol-Magazin. Accessible online at https://www.monopol-magazin.de/interview-fichte-diederichsen.

[10] Ibid.

[11] In this blog, I have already once described this position as one end of the spectrum of opinion in the debate about Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, whereby, as I see it, social and cultural anthropology has to “sit on the fence”.