The ›Mystery‹ of the Konkomba’s Severed Thumbs: Historical Fact, Colonial Rumour or Legend of the Defeated?

DCNtR Debate #3. The Post/Colonial Museum

»Forgetting and remembering are equally inventive.«

Jorge Luis Borges (1970)

The former ethnographic museum could reinvent itself by exhibiting not only objects but also stories. It is important to allow for anti-colonial resistance to be expressed in a variety of forms, in which the biographical dimension of the narrators is to be taken into consideration. This interweaving of life stories has the objective of highlighting interactions between people, and the reality of exchanges (rather than the classic ethnographic identification of cultural specificities). As such, accounts of anti-colonial resistance come in a variety of narrative forms. They may take the form of an enigma, a rumour, or a legend even perhaps, one that is not always corroborated by facts such as they are understood by the scientific community. This article proposes a narrative approach to the topic of restitution, of restoring to Africa goods that were looted during colonisation. In this case, the objects in question are human remains. Thumbs to be precise, the severed thumbs of Konkomba archers (Togo/Ghana) allegedly amputated by militias, first German and then French, during the anti-colonial revolts of 1884 and 1934. Accounts of such torture continue to be passed down to this very day, yet they are rejected as ›legends‹ by historians who can find no trace of them in the colonial archives. Should such accounts thus be denigrated?

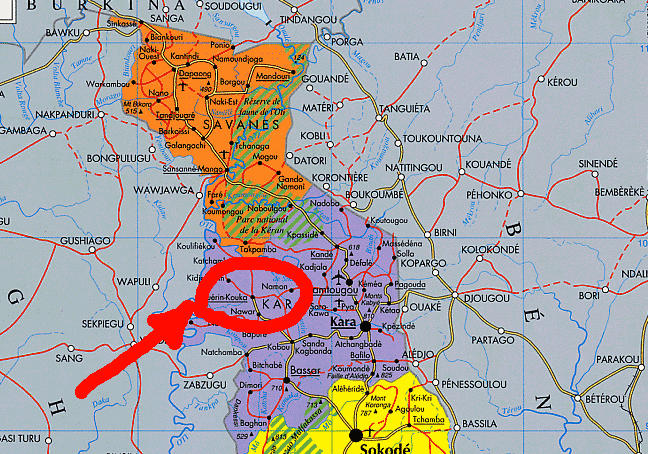

Seeking to examine the ramifications of such accounts as well as following up a childhood memory (I had myself heard this account in 1976), I revisited Konkomba territory in 2006, then again in April, and finally July of 2018. Though I did, I believe, find evidence tending to confirm the reality of this practice, my research – which is still ongoing – revealed certain surprising and disconcerting ways of retelling colonization. In this paper I argue that the debate on the restitution of looted objects cannot take place without taking into account the symbolic trauma engendered by colonization. Restitution, then, ceases to be simply a problem of museum conservation. As this specific story from Togo, which is part of my own biography, shows, the restitution debate is situated in a narrative knot which is currently precisely in the process of being unravelled. Can or should the museum be the place where these stories are transmitted? If so, what status should be given to these accounts and how should they be transmitted?

Fig. 1: A Bapuré elder showing how and why Konkomba archers’ thumbs were amputated by German militias in the colonial period. Photo: Bernard Müller, May 2018.

The Anecdote

In Ghana and Togo, the image of Konkomba archers’ amputated thumbs, severed by militias during the colonial conquest, is still raw in popular memory. The practice was first attributed to the Germans, and thereafter the French, though there is currently no formal, or rather scientific, evidence to support these claims. These accounts have spread well beyond the Konkomba region, yet there is no corroboration to be found in the military archives. The Konkomba are an unassuming people, and though they are certainly combative, they are modest peasants. Still, their stories are taken for mere fantasy. And yet the persistent transmission of this account poses certain questions. What if this was not just about verifying the oral sources (Gayibor 2011b) that allow us to understand the colonial phenomenon and its contemporary implications on a less factual but more symbolic level? To this end, we should have to relieve ourselves of the weight of the written tradition and, as in theatre, explore fiction in order to find the truth. We do so in the hope that such a step might finally reveal to us the ways in which history transforms the men who transform history, and the stories that constitute it.

But let us first ask how it is that this story has reached you, the reader of this text (taking an interest in the interstices of biographies and oral transmission).

The »Barrière de Pluie«: From One Memory to Another

It so happens that I was confronted with this story in 1976 when I was ten years old. We were living with my parents at the time, not far from Lomé, the coastal capital of Togo. We would occasionally visit friends living further inland, availing of the opportunity to discover the country. The road network was almost non-existent back then. Apart from a central axis that was more or less asphalted, the roads were rapidly deteriorating into mere tracks, more frequented by bicycles or warthogs than cars. We knew we were in the heart of Konkomba country, in the Dankpen, but no one remembers the name of the village where we stopped. Accompanied by a certain Kpakpatrou, a colleague of my father’s, we arrived in a village that had been indicated to us as Konkomba country, and proceeded to introduce ourselves to the elder of the locality, as was customary. As my mother recalled:

»the Germans brought Togo under their control around 1885 in a belated effort to find territories to ›protect‹. But they did not go unresisted, certainly not by the Konkomba. So sure were the latter of their invincibility while battling on their own territory that they came rushing into battle, claiming many of the aggressors’ lives. Ultimately, however, they were mowed down by European weaponry. Victorious but embittered, the Germans enacted a cruel revenge on every young man deemed capable of taking arms. They severed the thumbs of their right hands, making it impossible for them to hold a bow. The man we went to greet with Kpakpatrou was very old, dressed as an authentic Konkomba should be, that is, in a simple animal skin. He had personally survived those sinister times and Kpakpatrou discreetly drew our attention to the missing thumb of the revered old man’s right hand« (Denise Müller, interview on 25.04.2018).

In 2006, 30 years later, I revisited the Dankpen. It was one leg of a trip with the Togolese writer Kangni Alem, as part of preparations for an exhibition on colonial memory (the ›Broken Memory‹ project). We had decided to travel the old colonial route traced by the Germans up from the Atlantic Ocean. A light account of this journey was first published in 2009 (Alem 2009), earlier developed in a more detailed version in a blog (Alem 2006). I returned once again in July 2018.

Fig. 2: Konkomba. Map: Bernard Müller, 2021.

Dankpen Rebellious

»The entire Konkomba army is coming for me. I cannot possibly escape.«

Dr. Gruner, cited by Peter Sebald[1]

It is quite possible that this elderly man, who, it seemed to me in 1976, was no longer of any age, knew how to use a bow in 1896 when the German Valentin von Massow invaded his country. In the entirety of the German colony of Togoland at that time (which currently straddles present-day Togo and Ghana), it was in the Dankpen region that the greatest resistance to conquest took place, such as to inflict heavy losses on the invader. On 14 May 1895, a German troop stationed at Katchamba, and led by the German von Carnap-Quernheimb, was violently attacked by Konkomba warriors armed with poisoned arrows. But we should leave this turbulent military chronicle aside for a moment to consider the events of 1896, the extreme violence of which has left its mark on the popular memory of the region’s present inhabitants. Even the children here can trace the sequence of events, can point out where it happened, not, albeit, without indulging their imagination by adding a little twist of their own. At the end of November 1896, the expedition left Kete-Kratschi and headed toward Yendi. It consisted of four German officers or chargés de mission, 91 soldiers, 46 ammunition carriers and 231 simple porters. Massow and Heitmann directed military operations, while Dr. Gruner was in charge of the general, and political, coordination of the expedition as well as the signing of treaties. A fourth German, Lieutenant Gaston Thierry, would later join from Sansané-Mango.

Hans Gruner (1865–1943) is a key figure in the internal conquest of Togoland. Arriving in 1892, he was head of the ›colonial station‹ of Misahöhe for more than twenty years. Proudly bearing the title of Doctor of Philosophy, he was appointed head of the German expedition to the Togoland hinterland (›Togo-Hinterland-Expedition‹) from 1894 to 1895, and thus became the initiator of most of the treaties signed with rulers in the country’s interior.

Fig. 3: IboudjoCemetery, Dankpen (the site was presented tome as the final resting place of Konkomba archers killed incombat with theGerman militia).Photo: BernardMüller, 2006.

These, in turn, would give rise to the negotiations for the territorial formation of the German Togo. Despite his doctorate in philosophy, he published surprisingly little about Togo, where he lived almost uninterruptedly from 1892 to 1914. He would never publish his travel journals in his own lifetime, indeed, it was not until 1997 that these were edited under the title Vormarsch zum Niger: Die Memoiren des Leiters der Togo-Hinterland-Expedition 1894/1895. The memoirs provide detailed documentation of the methods and means used by the Germans in the conquest of the Togo hinterland from 1894 to 1895. There is no mention of amputating thumbs.

Fig. 4:Room with a view, Bapuré. Photo: Bernard Müller, 2006.

While returning from the famous battle of Adibo on 4 December 1896, which precipitated the fall of the Dagomba kingdom and, on the following day, the capture of the capital Yendi (present-day Ghana), German troops found themselves surrounded by an army of 7.000 Dagomba and Konkomba archers on »roughly 7 December 1896« (Gbandi 2009: 19). Despite their technological superiority, the conquerors suffered heavy losses. Rebel positions, in turn, were subjected to hails of machine gun fire and it is here that the thumbs of the young Konkomba would have been cut off to prevent them from firing their bows. It was this the thumb that would serve as support when firing an arrow, such as had set the Konkomba apart for their »determination and valour« (Cornevin 1962). There were heavy losses on both sides and Sergeant Heitmann, who was wounded on the battlefield, died of a poisoned arrow a few days later, on 28. December 1896, as did five other militiamen.[2]

The troupe accompanying the expedition consisted of ›police‹ that were stationed at Lomé. It was led by German officers (such as the ill-fated Heitmann) while its executors, policemen, civil servants and auxiliaries were all recruited elsewhere in Africa as local populations refused to enlist in the repression of their own. Following these battles, the Germans launched several campaigns following the simple principle of complete devastation, with a view to definitively imposing themselves. Writing in December 1897 after a fresh incursion into Konkomba country had put a temporary end to the revolts, von Massow stated: »basically, I reduced 40 to 50 villages to ashes, destroyed as many farms as possible, scattered nearly 300 head of cattle and 100 to 200 sheep…« (Von Massow/Sebald 2014). In the context of such extreme violence, amputating thumbs is unlikely to have been mentioned at all, as it would have seemed derisory compared to the other exactions, more brutal and deadly as they were.

From von Massow to Massu

A few decades later, the French sent in Lieutenant Massu in the rather unreasonable hope of putting an end to the chronic refusal of the Konkomba to submit to administrative rationalism. He would remain from April 1935 to July 1936. According to the historian Nicoué Gayibor, Massu »took the opportunity to strengthen the power of the canton chiefs, which was frequently contested, and to remind people of their duty to render taxes, it was to be the cause of significant unrest« (Gayibor 2011a: 508). He confiscated and burned nearly 300.000 arrows and arrow tips, as well as other war accessories (knives, finger tabs). The strophantus [3] which were used to poison the arrows, were systematically destroyed. A renowned public figure in France, Jacques Massu was a general officer in the military. A Compagnon de la Libération and former commander-in-chief of the French forces in Germany, he had distinguished himself in the Leclerc column in particular, as well as in the 2nd Armoured Division during the Second World War. He was the subject of some controversy for his roles in colonial conflicts in Indochina and, in particular, in Algeria, given his open acknowledgement of the use of torture during his time there. Concretely, he was accused by Algerian FLN veterans of having endorsed and even participated in acts of torture during the war in Algeria. Freshly graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy in 1930, he first cut his teeth as a second lieutenant in the colonial infantry during this operation of pacification, as well as other missions in Morocco and Chad. Though he would later go on to confirm the thrust of prior statements concerning his military activities in his book La Vraie Bataille d’Alger (The True Battle of Algiers), he at no point claimed to have participated in the amputation of Konkomba thumbs. Perhaps the manuscript of The Real Konkomba Battle will one day be found and published. To share one further anecdote, Massu returned to Konkomba country in 1979 and was »received with great pomp and circumstance […] The Konkomba offered him, not without humour, a magnificent empty quiver (without arrows!)« (Gayibor et al. 1997: 22).

Irrespective of the particulars of each soldier’s brutality, the presence of the two men has gone down in local history as exceptionally violent. Yet the similarity in their names provided the Konkomba with a chance to articulate the archetype of European military behaviour during the conquest: they are referred to as »masy« (phonetic transcription), meaning, simply, European soldiers. Whether this occurred in 1896 or 1936 makes little difference, given that the logic is the same. With thumb or without, on this point the Konkomba analysis is entirely correct. Of course, there’s something shocking about this crude chronological rendition, but what offends an historian may well fascinate the anthropologist, because, for the latter, an anecdote does not have to be true to be relevant.

From the Archive to the Ethnographic Object

To value the narrative drifts of oral history in no way implies an invalidation of the historian’s method. Instead, it invites us to read between the lines. The same is true for ethnographic collections; since the publication of Sarr and Savoy’s report in November 2018 – Restoring African Heritage: Towards a New Relational Ethics[4] – the historical conditions under which they were acquired is once again on the agenda. Thus, if we were to rely solely on the written evidence provided by museum inventory sheets, the real conditions of their acquisition would escape us. This was the case with the flute allegedly ›bought‹ by Gaston Thierry during an ongoing conflict.

Fig. 5: Entering the family house, Bapuré. Photo: Bernard Müller, November 2018.

In the ethnographic collections in Saxony, Germany (Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen im Verbund der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden), one object in particular caught our attention: a signal whistle (»Signalpfeife«, inventory number MAF 1268). Insignificant though this may at first appear, it actually facilitated the Konkomba in challenging German soldiers, as is attested in the archives (Klose 1906). Known to hunters, it functions by way of coded sounds indicating directions. The whistle was supposedly ›purchased‹ – there are grounds to doubt this – and integrated into the collection in 1900. Seemingly banal, it most likely provided Konkomba warriors with a means of taking their enemy by surprise given that the sound, which is similar to that of a particular bird, was unknown to the Germans. This function, militaristic so to speak, explains why it was seized by agents of Lieutenant Gaston Thierry when he came to the rescue of Gruner’s so-called scientific expedition.

Indeed, though no human remains resembling the Konkomba thumb phalanx can be found, German and French ethnographic collections are not lacking in Konkomba bows and arrows, nor are they short on flutes. The case of the severed thumb may not be a classic example of an object looted during the colonial era, but it nevertheless allows us to put our finger on an essential dimension of this debate, namely the aura of an absent object and the sheer quantity of strategies mobilized for its reinvention, even if it is thereby transformed. Objects live their own lives in a certain way, and the issue of the severed thumb testifies in this sense to the sheer volume of objects looted during the colonial era. Such objects are now housed in ethnographic museums in Europe and beyond. Such objects, like ghosts, can seem all the more present, paradoxically enough, by virtue of their absence. In any case, these objects become the accessory of an account for which their non-existence is the very condition of its possibility.

With German military archives supplying no documents to prove this practice, there are some who have concluded that this story was the result of an overactive imagination, that of a peasant and illiterate population, which has always been insubordinate and whose accounts ought not be taken literally. Without wishing to excessively probe that which is essentially an enigma, it remains the case that in Ghana, on the English-speaking side of Konkomba country, this matter is taken quite seriously. This is attested by the claim that

»old Konkomba men could show the severed thumbs of their right hand, a fool-proof method [sic!] to restrict their armed resistance as they could no longer use bow and arrow […] The left toe of the Kokomba was usually severed, for the Germans believed that they used the left toe on the ground to gather momentum while the right arm released the dangerous arrow from the bow that caused havoc« (Maasole 2006: 185, cited after Kachim 2013: 168).

As far as Togolese historians go, they are content to claim that »there is, effectively, an erroneous legend circulating in schools and according to which Lieutenant Massu […] ordered that Konkomba warriors’ thumbs be severed, so as to put a definitive end to the Konkomba revolts. This is not at all the case«. At most, they may also concede that it is not impossible that this »legend of the ›severed thumbs‹ […] was born of its quasi-homonym, 36 years earlier« (Gayibor 2011b).

A Touch of Theatre at the European Cemetery of Sokodé

On our journey to trace German colonisation in Togo in 2006, we left Konkomba country and arrived 100 km and two hours later in Sokodé, capital of the plateau region. Kangni Alem writes in his diary that

»the welcome at the hostel was simple and the grilled chicken excellent. A man approached us while we were nibbling our skewers and sipping our beers. Friendly and talkative, he soon came to understand the purpose of our stay in Sokodé – the search for traces of the German conquest of Togo – and offered to be our guide for the next day. Or at least, he acted as though he had understood, he swore he would take us to Mango (another town altogether), to show us the cliff from which, he explained, sorcerers and other great criminals of the community were thrown into the void in ancient times. I asked him if it was true that there was a place in Sokodé where one could see chains sealed in the cement of the tombs… ›yes, yes‹ he said, brimming with excitement ›tomorrow I’ll show you the prisoners buried with their chains‹. I was positively hopping with excitement: was the story true? Who were the men buried in this cemetery? What had they done? Our friend was hesitant to recall. In a very elegant gesture, he had the honesty not to speak any further, and we decided to meet the next day« (Alem 2006).

It was there in Kotokoli country, far from the Konkomba, that our investigation was to take on another dimension. It was an opening, one which – as we had set out on this parallel road, almost abandoned by the living but host to more ghosts than we could possibly have imagined – had not been foretold.

As we entered the cemetery, we saw a young man perched on the fence with whom we spoke, explaining the reasons for our visit. A whole group of youngsters in khaki school uniforms soon joined, followed by other onlookers. There then followed, in the middle of the cemetery, an erratic discussion as to how the colonial past ought to be discussed today, and the nature of its impact on the current state of Togo and the world. The ideas flowed freely; colonial violence was broached with a mix of condemnation and the regret of still living under a dictatorship that basically operates under the same principles, the same apparatus. »The only thing that’s changed is the administrator’s skin colour«, one secondary school student said.

Fig. 6: The broken chains of the European cemetery of Sokodé, capital of the province of Centre and the prefecture of Tchaoudjo. Photo: Bernard Müller, May 2006.

An impromptu school class occurred and just as we were about to visit the graves, one of the schoolchildren remembered that he had an old magazine with an article on the cemetery. Convinced that the text contained information that would aid the discussion, he went to look for it. He returned with issue 99, dated May 1985, of the now defunct Togo Dialogue magazine, in which the French sociologist Jean-Claude Barbier had written an interesting article entitled »A cemetery amongst the green«.

Over the course of the discussion, a surprising turn of events occurred, whereby the children of yesterday’s victims sat at the bedside of their persecutors’ remains. As Kangni Alem recalls:

»Bernard took out his camera to film Mr Dehée’s grave. I asked one of the youngsters if, by any chance, he knew why there were chains around the central monument. Without hesitation, he answered that the white man buried in the tomb was a prisoner, so the chains were put there to distinguish him from the others. A splendid explanation, but the other school kids were not convinced. Another student corrected him: no, the man in the grave was a prisoner, true, but he hadn’t served all his years in prison, so they put his soul in chains so that he could finish his sentence in the afterlife. Naively, I replied: ›his crime must have been horrible for them to punish him like this, even in death.‹ When did he die? How many years did he have left to serve? How can he now be unchained, beyond death? Is there a ritual for doing so?« (Alem 2006)

Against all expectations, the youngsters seemed to be interested in the fate of those Europeans, some of whom were not much older than they were. They wondered what sense of respect Europeans could have for their dead, given that, according to the rumours in the neighbourhood, the children’s graves were never visited by their parents. The rituals required were never performed, leaving the souls of these ›whites‹ in a perpetual state of wandering, the effects of which could prove dangerous for everyone. There was no doubt in the mind of the young audience that if the ceremonies had been carried out, the chains would have been broken and the souls of the prisoners thus freed. In chorus, they wondered: »don’t the families over there in Europe know about this? Aren’t they suffering the consequences of this abandonment?«

Beware of Anecdotes…

The poet-philosopher Emil Cioran once stated: »doctrines vanish, anecdotes remain« (Cioran 1997). We are thereby reminded that the very stories that circumvent the facts are often those that come closest to them. In praising the anecdote (ἀνέκδοτα; ›unpublished/ unprecedented fact‹), it is not that I wish to pontificate on the virtues of the rumour, nor do I wish to problematize the very objectivity that I share with historians as an anthropologist. Rather, it is a question of demonstrating that these narrative convolutions, which account for facts that evade our evidence-based system, provide us with a truth nonetheless. The anecdote refers to a detail, to a secondary aspect that is not stated in the main account, and which is also ›unpublished/unprecedented‹ in this sense. Paradoxically, it allows us to articulate its core components, at times to expose its most genuine of components. The imaginary at work in this narrative energy reacts to the aphasia generated by colonial epistemic conditions, the extensions of which are still with us today. The very transmission of the present narrative attests to this. It is very much this present form of a certain past with which we are now faced, and it is also undoubtedly to this very same end that it is transmitted to us in this particular manner. It is in keeping with Achille Mbembe when he states that »Europe has taken something from us that it will never be able to give back« (Mbembe 2018). Nevertheless, the void thus created cannot so much be compensated with financial compensation as with

»a symbolic re-establishment through a demand for truth. Compensation here consists in offering to repair the relation. The restitution of objects (having become the nodes of a relation), also implies a fair and just historiographic work and a new relational ethics; by operating a symbolic redistribution repairing the ties and renewing them around reinvented relational modalities that are qualitatively improved« (Sarr/Savoy 2018: 40–41).

The current debate on the restitution of goods looted during colonisation appears to be just the tip of the iceberg, there is an ocean of stories hidden beneath. In so far as it highlights epistemic violence, this contribution also seeks to highlight the symbolic dimension of the restitution of goods looted during colonisation, the stakes of which go well beyond the simple movement of objects from one place to another. It seeks to call attention to other forms of knowledge production, highlighting the diversity of explorations of the world »with, against and beyond the heritage of Western epistemologies« (Mignolo 2000: 9). These regimes of truths (Foucault 2001) do not preclude one another, they are intertwined. They »archipelagise« one another (Glissant 1997) by crystallising various traditions of thought, aesthetic modes or heuristic regimes that refer to social and historical contingencies, and which we would do well to consider in their narrative creativity and their propensity for the anecdote.

What becomes of the memories that evaporate? How are they sublimated? The colonial enterprise continues to be steeped in ambiguity. This, and whatever meaning it is we should give to it today, are illustrated all too well in the Dankpe, through the enigma of the thumb and all the vagaries that surround it. To this extent, the Konkomba are asking themselves pertinent questions, through which colonial history is reflected as an enigma, to be seen more or less everywhere. It is met with a mixture of condemnation and intrigue for all the change that it has caused in the world, and of which we would do well today to take stock; for we are asking ourselves the same questions.

Conclusion: a Point of Honour?

The case of the severed thumbs – an atypical example of colonial plunder though it may be – tables one essential dimension of this debate on which we can now definitely lay a finger. Specifically, that of the aura of absent objects and the sheer quantity of strategies by way of which they are reinvented, though this may mean their transformation.

Akin to what in neurology is known as pseudohallucination or phantom pain the severed thumbs continue to feel. It is a finger that touches us. The reactions provoked by its mere evocation go to show, in their own way, that it moves still, detached though it is from its previous body. Objects live their own lives one might say, and it is in this sense that the case of the severed thumb testifies to the existence of the many objects looted during the colonial period, sitting now in so many ethnographic museums in European and beyond.

It seems, in certain cases, that these objects continue to act. Like so many ghosts, their presence is all the greater – paradoxically – now that they are absent. At any rate, they become the accessories of a narrative for which their non-existence is the condition of possibility.

The touch of theatre at the Sokodé cemetery shows us a way forward: colonial history can only be overcome if it is done through a collective work involving both the victims and the colonisers of yesterday, through an exchange of ghosts, a barter of traces, a bazaar of stories… As people reinvest in colonial history ever anew, they articulate events into accounts that decompose with each passing day, without ever really disintegrating. They will always know, albeit confusedly, that colonization was decisive in the history of their family and their community, in the history of humanity. What status should be given to these narrative drifts? What status should be given to this oral history? By making a fool of academics, museum professionals or restitution specialists and all those who today refuse to give credit to the story of amputated thumbs, the people who today perpetuate this narrative, like this old man with a cap with the astonishing graffiti…

Fig. 7: An old Konkomba. Photo: Bernard Müller, May 2018.

How can these accounts be heard? And, if it should turn out that ethnographic museums, the main holders of colonial collections, could indeed become appropriate sounding board – what kind of structural reforms would have to be undertaken, what operations of decentralisation and decolonization would have to be carried out so that this institution, born of colonization, could become a theatre for a dynamic recomposition of the imaginary, rather than a cabinet of ethnography gone rotten?

Translation from French by Michael Dorrity.

The print version of this text is published in the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften, issue “The Post/Colonial Museum”, 2022, p. 93-105. In order to make the issue “The Post/Colonial Museum” available to a wide readership, specifically on the African continent, we decided to use the long standing collaboration between boasblogs and the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften to successively publish all contributions in print and online (as DCNtR debate). We thank the editorial boards of both, the Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften and the boasblogs, as much as the publishing house transcript for embarking on this project together. Furthermore, our thanks go to the participants of the conference on Museum Collections in Motion, which was generously supported by the Global South Studies Center, University of Cologne, the research platform “Worlds of Contradictions”, University of Bremen, the Museumsgesellschaft of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum and the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Most of all, we thank the contributors to this debate for four years of exchange, debate and intellectual companionship.

Footnotes

[1]Original quote: »Das gesamte Konkombaheer will mich hier angreifen. Ich kann nicht fliehen.« (Sebald 1988: 192, then note 109 on page 706 (ZStA = Zentrales Staatsarchiv der DDR, Potsdam, Nr. 4392, Bl. 90). Translation by Bernard Müller.

[2]»Mitteilung« from the German archives DKB 1895: Sergeant, Police master, born 01.03.1869 in Rüete, district of Hamm, »auf einer Expedition mit Eingeborenen gefallen« on the 28.12.1896 (294; 1897, 166), cited in Sebald 1988 : xxx.

[3]The highly toxic seeds of strophanthus gratus were once commonly used in the preparation of poison for arrows: they were ground with the sticky juice of the plant and the tips were dipped in this mixture.

[4]Presented by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr to the President of the Republic, Emmanuel Macron, on 23 November 2018.

References

Alem, Kangni (2006): Carnet de route ›Togoland‹: un cimetière à Sokodé (Inch’Alem, le blog de Kangni Alem, http://kangnialem.togocultures.com/carnet-de-routetogoland-un-ci- metiere-a-sokode/ (25.03.2021). Alem, Kangni (2009): Dans les Mêlées – Les Arènes Physiques et Littéraires, Yaoundé: Editions Ifrikiya-Collections Interlignes.

Borges, Jorge Luis (1970): Le Rapport de Brodie, Paris: Gallimard.

Cioran, Emil (1997): Cahiers 1957–1972, Paris: Gallimard.

Cornevin, Robert (1962): Les Bassari du Nord Togo, Paris: Berger-Levrault.

Foucault, Michel (2001): Dits et Écrits II, 1976–1988, Paris: Gallimard.

Gayibor, Théodore Nicoué (2011a): Histoire des Togolais: Des Origines aux Années 1960. Le Refus de la Colonisation, Volume 4, Paris: Karthala.

Gayibor, Théodore Nicoué (2011b): Sources Orales et Histoire Africaine. Approches Méthodologiques, en Collaboration avec Moustapha Gomgnimbou et Komla Etou, Paris: L’Harmattan. Gayibor, Théodore Nicoué (Ed.) et al. (1997): Le Togo sous Domination Coloniale (1884–1960), Lomé: Presses de l’Université du Bénin.

Gbandi, Adouna (2009): Description Phonologique et Grammaticale du Konkomba, Langue Gur (voltaïque) du Togo et du Ghana – Parler de Nawareé, Université Rennes 2, Université de Lomé, https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00416375 (14.04.2021).

Glissant, Édouard (1997): Traiteé du Tout-Monde, Paris: Gallimard.

Kachim, Joseph Udimal (2013): »African Resistance to Colonial Conquest: The Case of Konkomba Resistance to German Occupation of Northern Togoland, 1896–1901«. In: Asian Journal of Humanities and Social Studies, 1:3, 62–72.

Klose, Heinrich (1906): »Musik, Tanz und Spiele in Togo«. In: Globus, Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Länder- und Völkerkunde 89:5, 69–75.

Maasole, Cliff (2006): The Konkomba and their Neighbours, Accra: Ghana Universities Press. Massow, Valentin von/Sebald, Peter (ed.) (2014): Die Eroberung von Nordtogo 1896–1899, Bremen: Edition Falkenberg.

Mbembe, Achille (2018): »La Vérité est que l’Europe Nous a Pris des Choses Qu’elle ne Pourra Jamais Restituer«. In: Le Monde, 01.12.2018, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/ article/2018/12/01/achille-mbembe-la-verite-est-que-l-europe-nous-a-pris-des-choses- qu-elle-ne-pourra-jamais-restituer_5391216_3212.html (14.04.2021).

Mignolo, Walter (2000): Local Histories/Global Designs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Boarder Thinking, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sarr, Felwine/Savoy, Bénédicte (2018): »The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics«, http://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_en.pdf (14.04.2021).

Sebald, Peter (1988): Togo 1884–1914. Eine Geschichte der deutschen »Musterkolonie« auf der Grundlage amtlicher Quellen, Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Bernard Müller is interested in artistic approaches that draw from the toolbox of ethnologists or ethnographic methods of investigation as artistic process. He focuses on processes of staging and narrative, whether they be stage devices (theatre, rituals, performances, etc.), museum scenography or narrative fictions. A specialist in the cultural history of West Africa (Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana), he is also developing his comparative research in other areas (Europe and Brazil). Since 2003, he has been leading a seminar at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales(Paris) and is a researcher and member of the Institut de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les questions sociales(IRIS = UMR 8156 – CNRS-Inserm-EHESS-Université Paris 13). He is professor of anthropology at the Ecole Supérieure d’Arts d’Avignon, and lecturer at the Institut für Ethnologie in Cologne (Germany).