The Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

A place to forge new connections to the objects

Interview[1] with Emmanuel Kasarhérou.

“When it comes to creating exhibitions, a museum constructs certain approaches, it looks at areas, some of which don’t lead anywhere, it explores them nonetheless. That’s the role of the institution, so let’s explore now”.

The new director of the Quai Branly Museum Jacques Chirac, discusses his research design with Bernard Müller, professor of anthropology at the Ecole Supérieure d’art d’Avignon and lecturer at the University of Cologne.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Is it recording?

Bernard Müller: It is, yes. My dear Emmanuel Kasarhérou, what is your vision for the research you wish to implement at the Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac, of which you were appointed director last spring (May 2020)?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Well, firstly, it’s true that the museum is peculiar in so far it is founded on two departments, a collections department and a research department. And this is an advantage as compared with other museums, which have to do research, I was going to say, only marginally. Often because they are not structured in quite the same way.

As such, we’re quite lucky to have a research department, which is open to other disciplines, mainly anthropological and historical. We’re also lucky as far as the current research director is concerned. He’s also quite open to other disciplines in terms of material analysis; disciplines that pave the way for the use of new technologies as applied to the world of collections.

Of course, the museum had anticipated and carried out this type of work already but I think a further dimension was added to the museum’s main axis. This has obviously been in development since the museum opened. Principally in the field of anthropology. There’s been a focus on the history of collections for a little over a year now, ever since legitimacy, the history of collections, the colonial period and so on, all started to come under question. These historical disciplines are probably those best represented at the moment in terms of research being carried out at the museum. They aim to give some clarity as to how the collections are constituted and to put together as many documents as possible. That is to say, the way in which museums were formed. It’s often the case that Information related to the context in which the collections were acquired has been dissociated from the collections themselves. And so today we find ourselves with the institutions in possession of the objects on the one hand and on the other, the archives themselves, which are very widely dispersed. Today, the challenge is to find the collections of archives with links to the collections we have and to bring them together, to establish a unity around the object.

Alas, this has not been carried out uniformly at all times because the collections have a good 400 years of history behind them. So the movements have been different and we need to establish coherency, in a sense, by way of a sort of treasure hunt that consists in looking up the information, which itself is often very diluted. I think the best example of this is the work that was carried out on the collections inherited from Général Alfred Dodds (1842-1922) who led the conquest of Dahomey (now Benin) between 1892 and 1894, deposing King Behanzin. Gaëlle Beaujean’s, Head of Africa collections at the Musée du quai Branly, painstaking work[2] consisted in seeking out information, the better part of which was clearly not to be found in institutions that had preserved the objects. Rather, it was quite widely spread, often in personal diaries of which there is not necessarily much trace. By searching, however, one finds different clues that, little by little, lead to conclusive information. As such, there’s a great deal of very important and very long-winded work to be done. In Dodd’s case for example, it took nearly ten years. It was finished two years ago, which allowed us to document the restitution of the objects.

Bernard Müller: Indeed, and on this question of a treasure hunt, this research, the recomposition of a scattered mosaic of pieces of information that can be found all over. How would you, perhaps you are doing so already, but how, ideally, would you like to go about it? By referring to other means of knowledge production, other means of transmitting local stories and local history…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Well, I feel like that’s a second step!

Bernard Müller: …and other associations, writers, that is, beyond the scope of research carried out by universities, in academia, or beyond the scope of museums even. The EPA in Benin comes to mind for example, the school of African Heritage, but there are also other…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes, of course.

Bernard Müller: …other archival collections such as oral archives.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Well they’re different techniques, and it’s not necessarily the same people.

Bernard Müller: Is this a priority for you, does it follow your line?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Of course, but there’s a different bias there because everything that falls within the purvey of oral history is not processed the same way. Personally, I’ve spent time gathering information in Caledonia; Kanak oral memories. And this social memory, which is not individual memory; it’s a memory that follows its own social codes. As such, these really are different techniques that ought to be awakened. As I see it, this is a second step though. It’s a second step because we’re not yet equipped to do this straight away, it comes afterwards.

In order to mobilise this oral memory, the easiest thing to do is apply it to practical and precise cases. For example, we’re currently putting together a project with the museum of black civilisations in Dakar, which is still in its preliminary stages. We want to work together on the Djibouti[3] map. For our part, we would be mobilising European archives, photos, papers, manuscripts and so on. Whereas they would be mobilising oral archives, meaning memories and recollections, and to see to just what extent these actually exist. The societies themselves aren’t necessarily stable and we can’t take a photo of something that happened in 1930 and another of what’s happening today. Perhaps it’s possible in certain places, the material might be there. It’s just this sort of thing that Amady Bocoum, current Director of the Museum of Black Civilisations in Senegal, appears to be interested in, that is, in using, in some sense, this piece of congealed reality. The work of that project is to create a sort of freeze frame that can be compared with another, which could be acted out today. The actors would be different of course, they would be actors from the area who could mobilise their own local memory in order to produce new knowledge, which…

Bernard Müller: Exactly! That’s it exactly.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: …which is about this relationship to history. But in order to do so, we’d still have to bring certain historical documents to the table.

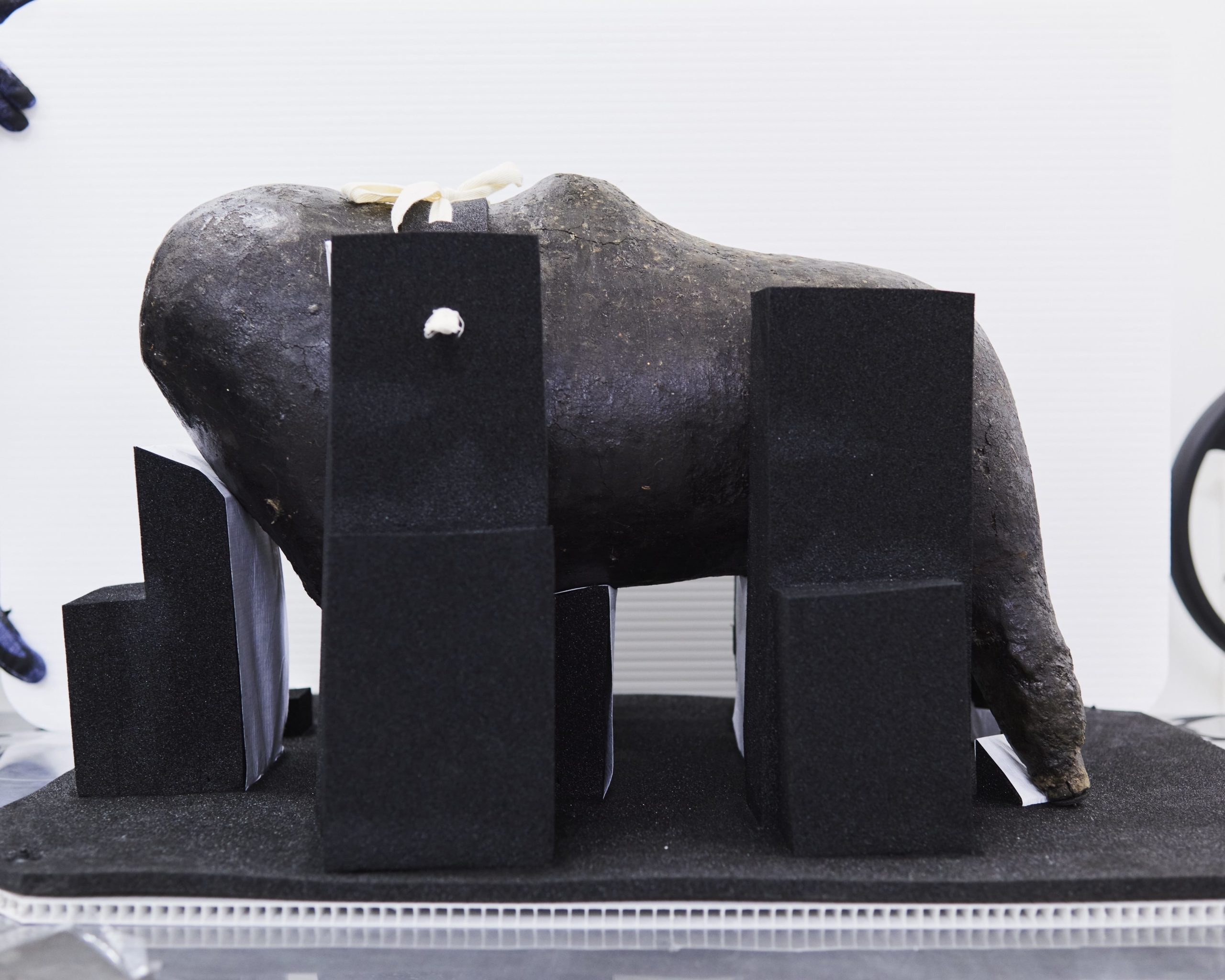

Foto report in the storerooms. Octobre – November 2017. © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Cyril Zannettacci

The objet représente is a cultual objet : Boliw Mali (Donation Archinard[12] : 71.1902.12.4.).

Bernard Müller: Indeed, it’s a collaboration of course and these are new ways of collaborating.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: That’s why as far as I’m concerned these are in fact two different steps. The first is to mobilise particular points. That is, we first identify certain points in the collections, for which material that could be revisited exists, and we try to find partners who could fulfil this role. In terms of the Djibouti map, it’s extremely ambitious as it is likely to be an enormous undertaking. I mean, it’s already enormous in terms of the objects, the documents, the recordings and other appraisals. We haven’t simply been collecting objects. We’ve taken note of the languages, of the songs. We’ve done quite unbelievable work and it’s now a question of remobilising and showing that while the objects constitute a sort of framework, there’s an entire edifice that’s been forgotten and which is itself quite considerable. It’s also worth what it’s worth because this is clearly work that was done quickly, very urgently. Despite everything, it allowed us to get an overview of all aspects as seen by an outside observer at any given moment; linguistic, social and cultural. There’s something there, which could nourish local cultural interest as well in my opinion. Not just the cultural interactions of scientists, but a local interest that would allow for a reinvestment in local dynamics. I’ve seen the interest in reflection myself when we carried out inventories of Kanak heritage for example. Every year we had a meeting with local collectors in New Caledonia. It’s interesting to see what the people themselves are actually interested in. It was not necessarily the same things that would be of interest to a scientist forging a career in Europe…

Bernard Müller: Yes, exactly.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: … but it was the technical possibilities that they were interested in. The technical questions were quite interesting.

Bernard Müller: The savoir-faire…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Indeed! The savoir faire!

Bernard Müller: …utilitarian you might say or…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: You had the impression they were…

Bernard Müller: …like recipes for…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: that’s it yes.

Bernard Müller: …for precise manufacturing methods, let’s say, clear-cut one could call it…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Quite clear-cut for objects with which we knew we were losing a connection. The fact that the object could resurge, that we could study it from a technical point of view. This caused a stir in the memories of the elders, of techniques that had been considered forgotten and that had resurfaced. There are peculiar colonial situations such as that of New Caledonia for example, where a lot could be done with scale models. That is, one couldn’t build large boat so one made models, one couldn’t build large ceremonial houses, so one made models of them and, as it turns out, many of these models were then sold to tourists. When you examine the interiors of these objects, they’re technically accurate, that is, the parts that you can’t see are technically accurate. It’s as if producing the model had a double purpose. At once commercial, because one could sell them to passing tourists, but also technical because by virtue of constructing it, one could teach the method used to make the particular knots for holding a certain structure in place for example. There must be a number of objects for which the same is true in that they were sold to tourists but they also constitute a sort of technical manual that ought to be reopened and reinterpreted. As such, we need to have the keys for such reinterpretation.

Bernard Müller: Absolutely. It seems as though this production and reappropriation of popular knowledge is developing somewhat on the margins of the university and classical research. This model, for example, becomes a place of local knowledge production, reappropriated due to local interest, which is not necessarily academic.

Model of a canoe, wood and plant fibres, musée océanien de La Neylière. © Clémentine Débrosse

https://casoar.org/en/2018/03/28/linventaire-du-patrimoine-kanak-disperse-se-retrouve-au-musee-anne-de-beaujeu-a-moulins/

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: These are the interests at the moment.

Bernard Müller: It’s very much integrated into people’s day-to-day lives just now…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Its quite current yes.

Bernard Müller: As I understand it, you’ve also been interested in other living things, that is to say artistic works, for some time now, is that so?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes!

Bernard Müller: In your own research concept, is the artist someone who can also explore, more than that even, who can identify certain areas, such as the models, certain objects of interest? And who can both shape and produce them?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes, of course. Sometimes the artist is a technician and so the technique is also of interest. In my view, artists are themselves a way of re-actualizing heritage, of giving it a contemporary echo.

Bernard Müller: Of situating and resituating heritage?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes, because some of these objects are so distant in terms of their relationship to a particular society. Even if that society produced them at the beginning of the 20th century, it’s so distant today that one needs to find a link, and this link is at once intellectual because it’’s a link to heritage, it’s the construction of heritage and in a lot of societies heritage needs to be constructed. I don’t think heritage can be taken as a given, it’s something we construct and this is what we’ve tried to do in New Caledonia for example. That is, certain objects had departed entirely, and when they’re brought back, there’s not necessarily a set place waiting for them. It’s been taken already. As such, we need to construct new places, to forge new spaces to keep them. Cultural centres and museums are precisely the sort of place for where a link of reappropriation with the past can be constructed. But it is a construction and we need to be aware of this. That is to say, it is of interest only because there is a form of legitimacy and resonance in relation to a present and living society. This will likely be formulated in some other way 50 years from now and it is this living side of things that is genuinely interesting. Hence, I am very much interested in the artist. This is someone who can, not give new life, but find contemporary echoes in past forms, which will never be restored. Forgotten rituals are like words on the wind but there’s a certain attitude, a posture vis-à-vis certain questions to be found. But the ritual itself has most likely been deleted completely. As such, I think the artistic act can transpose one type of ritual, which will never resurface, to a type of modern ritual that is itself precisely the artistic act, a sort of transposition. Again, these are constructions and one constructs on top of things that are themselves constructions, so what we have is a sort of intellectual archaeology for which the collections and the information that surrounds them are the bricks that we can assemble, dismantle, reassemble. It’s a game, as such, that allows us to situate ourselves in space and time. And it’s clear that conceptions of time are very different from one society to the next. This game can be very productive or it can bypass certain societies completely. So, it’s not the priority at the moment when one takes an interest in it. On the contrary, for many it may come at a moment of reflection on some common destiny, of sharing some reconstruction of a particular past, which has probably not existed in this form but which will serve as a base for a society seeking to establish itself at some particular moment. I’m curious to see what will happen to Abomey’s objects. It’s clear that people are waiting for them but there’s no longer a specific space for them, one has to be found or established. We need to forge a new connection with these objects. They are still strong and there will probably be a whole series of inventions, well, inventions… the term should not be taken pejoratively, but let’s say creations, that allow us to find these objects again; to enable them within current perceptions as well as in relation to their past, to ritual and so on, because they are not completely neutral objects.

Bernard Müller: There’s an idea of the museum that I find very interesting; conceiving of its role as a creator of space for reappropriating of an object’s history, putting it back into play. There’s a logic of humanist progress that is not without an element of utopia.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s a conscious utopia, meaning that we know we’re in the process of construction. This is the artisan side, the artistic side of things, if you will.

Bernard Müller: Indeed, and in this attempt, if you will, of trying to implement this utopia, would you say that, given your vantage point; that the institution blocks, or could block, more than encourage, the creation of new spaces? What are the institutional blockages? How can these somewhat obligatory partnerships between equivalent institutions from one country to the next cause blockages? Or could they be conducive to the process? This reconstruction of a space, which seems to me something genuinely luminous, the creativity that it implies is not necessarily the creativity that characterises cultural and political institutions.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Precisely for that reason, the recourse to, and examination of, artists allows us to push through with certain ideas. After which, things should be discussed rather than forced. It’s a collective work and in so far as the conditions are not fulfilled, nothing happens. But this is not to say it will never happen. At some stage we have to fall into step with one another and act together with the same urgency. But there are a lot of partners and for me the most important thing is to work with colleagues in museums who support this idea, who have the same desire. You can see this with Amady Bocoum for example. We know each other well and I can see that this is something that interests him and resonates with him in a similar way. So clearly, there’s an opportunity at some point. For me, heritage is above all a question of encounters and personal convictions.

Bernard Müller: The possibility with which you are presented at the moment in terms of creating new situations; is it just accidental as far as the institution is concerned? As far as the institutional process is concerned, is this a bonus or is it the actual objective? Do you see my point?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: This is part of what a museum is as far as I’m concerned. When it comes to creating exhibitions, a museum constructs certain approaches, it looks at areas, some of which don’t lead anywhere, it explores them nonetheless. That’s the role of the institution, so let’s explore now. In terms of the project with the Museum of Black Civilizations that I mentioned earlier; we explore. We don’t know if we’ll make it all the way but we start together and we do something. I think that what’s important in terms of these colonial periods, in fact, is what we try when we can. It’s not always possible, there might not be anybody at the end of the line in the end, in which case it’s the reconstruction of the reconstruction of the reconstruction. It’s more random, that is, you start speaking to someone on behalf of someone who themselves are speaking on behalf of someone else and in the end you don’t know who’s on the other end of the line. It’s a bit like the Ziggurat that no longer has a base, it just doesn’t go anywhere. It’s good to ask yourself who you’re speaking about from time to time.

Bernard Müller: Yes, who speaks or who has the objects speak in terms of demands for the restitution of objects despoiled during the colonial period?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: For the moment, such relations occur between states. At heart it’s very dubious because it was not the states that created these objects nor did states exist in their current form at the time. These are often societies that themselves no longer exist today, with world views that at times have become rather remote. It’s worth bearing in mind what you are building on and knowing how to criticise the approach you use. For me, these heritage projects are human constructions and they’re extremely interesting precisely because they forge links to a certain period and to a moment of clarity. I don’t know if I would do the things I did 25 years ago in the same way again today because I’ve evolved, as has the society in which I work. For that reason, I think this is part of the role museums play because they create this sense of reconstruction, it’s an intellectual exercise. I’ve always defended the idea of the museum, even in the face of people from the same culture as myself who would say it was a European idea and hence fundamentally didn’t belong here. What I try to say is that it’s a European idea that had just as little to do with the European societies that were busy plundering sacred objects and recomposing them. But on the other hand, it’s an idea that creates a space for play. Of course, they were not deigned to do this, rather it’s the space created by them that subsequently allows for play, for reconstruction. This is why the Tjibaou cultural centre[4] was created, for this same reason, that is, a new space that lets us take a step back from certain practices without undoing them altogether. Custom is custom after all, and the chiefs are the chiefs, religious convictions are religious convictions, magic is magic. There’s a space, however, in which one can take some distance from one’s own practices and this is what can be of interest to the individual or to society in a more global sense. Then, of course, when this becomes an ideology where you go around telling everybody how to live their lives…

Bernard Müller: Is there pressure?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s clear from the case of the Nantes Museum with the Genghis Khan[5] exhibition when China attempted to force its own vision, that is, to suppress significant imperial and Mongol vocabulary, and so on, in favour of circumlocution that ultimately denied the facts. The museum refused to along with it, which was very courageous! Now that’s a museum, keeping up with the demands of the democratic game. After which, whether you like the exhibition or not, a stance has at least been taken by a group of individuals at a certain point. Sometimes this is carried out by commissions or sometimes by the museum given that it’s the latter that ultimately has to play the game. So, there are certain limits as we’ve seen just now. That case was rather recent, which is why it comes to mind. I don’t think it ever happened anywhere else, whereby the museum could be so completely diverted. Clearly there can be institutions referred to as museums but which really don’t resemble them in any way.

Foto report in the storerooms. March 2009. musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Françoise Huguier

Bernard Müller: Have there been attempts to censor material?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes, at any rate, there have been attempts to rewrite certain things, which try to erase a critical approach for example, or critiques of such an approach whereby somebody says “I wouldn’t look at it that way myself, I wouldn’t use this or that phrase” and so on. This is really the role of museums. A museum is a democratic object that survives on public funds. I think there’s a rather false impression that is often implied, or indeed stated explicitly, that museums are businesses. Nothing could be further from the truth, there’s not a single museum that makes money. If it does, it’s no longer a museum, it’s a treasure chest that charges a fee or that organises a sort of Play Park around certain objects and ways of presenting them, or of scenography’s, but it’s no longer a museum in any sense that I understand. So as such, I think you’re very linked to the society that employs you and which can afford the luxury of a space where its relationship to itself, to others and to time can be interpreted.

Bernard Müller: And does this public inking of the museum, in France at any rate or in Europe, or at least continental Europe; does this impose social themes? Does it impose a certain philosophy or an approach of mediation? Doesn’t the issue of restitution automatically take a central role in a museum’s life given that it was evoked by the President of the Republic during his now famous speech in Ouagadougou[6], on the 28th of November 2017?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s undoubtedly the case that, on a topic like this, whatever the President of the French Republic says carries more weight than, say, the Queen in the case of England. But we can also see the cultural differences that are expressed, and that’s very interesting. For me, a museum is successful when it comes to resemble its country and its history. A museum that is interchangeable with others is suspect. The Guggenheim, which is slowly becoming the same the world over, is much less interesting than a Guggenheim that is Basque or American or whatever else. Ultimately, it’s the anchorage it has in a society that gives it legitimacy in the eyes of museumgoers. It’s easy to see here, 80% of our visitors are French nationals. So it’s not an object that’s up for sale. It serves as a point of reflection: What are we? What have we been? Who are the others? What is our relationship to others? How has it been in the past? What can we see in it? What is ultimately indistinguishable in terms of one society’s relationship to another? What is it of the one or the other that remains intimate? Where are the misinterpretations? How might false meanings produce understanding? Sometimes misinterpretations are fundamentally erroneous but they can be extremely productive from a cultural point of view. Ultimately, this is the reflection we’re left with.

Bernard Müller: So how exactly should these social questions be integrated into the programming at a museum like the MQB? There’s been a return to the colonial of late and this is particularly relevant for the MQB given that a significant portion of the Quai Branly collections were collected in the context of colonisation. As such, what does this return to the colonial say about France and what stance does the MQB take?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I think this speaks to the world more generally because I think it questions countries in different ways depending on their history. But are we really in a period of post-colonialism?

Bernard Müller: Considering the situation in New Caledonia for example. Are we already on the other side or did we ever even traverse it? Perhaps both are true.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I think there’s significant part of that population who never really had any idea of all the things that could be happening elsewhere. I think that people with a neo-colonial mind-set exist in a sort of bubble, it’s clear that people felt like they were in bubbles. There is, perhaps, a sort of common culture of diffusion that avails of biology, technology and so on for domination. Ultimately though, what difference does that make to a 19th century farmer in Roannais? I don’t think there’s much awareness on the topic. For this very reason, I don’t think we should become prisoners of these words either. What I do think is important is that we look at the particular situations. Take New Caledonia for example, colonisation was quite unique there. It’s the only place where there were indigenous reserves. There have been French colonies all over the planet and it’s the only place where indigenous reserves were formed. People are parked, there are exit permits, there are specific taxes. It’s true that specific taxes can be found in many colonies but it doesn’t happen everywhere at the same time nor does it happen in the same way. This is why the act deserves so much respect, it’s worthwhile saying “there’s an enormous area that we need to take another look at”. But you do have to look closely because it’s not the same history in Cameroon as it is in Togo, nor is it same in the Ivory Coast. Senegal’s history, for its part, is entirely unique. It even had French communes at one point, Algeria even more so. Even within the same region, situations can be totally distinct. So I think it’s time for re-examination. Indeed, all the more so now that we have the chance to look at certain situations from a greater distance. You can’t do this the same way with contemporary situations as there just isn’t the space to benefit from hindsight.

Bernard Müller: I think we’re also at a fundamentally different point in world history, one of rediscovery. This rediscovery, if we can call it such, seems even stronger in Germany than it is in France. In Germany, which lost its colonies directly after the Second World War, the violence that accompanied its whole colonial project, not just the conquest, has gone ignored for the longest time, at least in terms of public opinion. Though this rediscovery may well seem naive, its provoking serious unease in Germany as the brutality of the conquest of what was later to become Namibia is exposed. The will to systematically eradicate an entire section of the population is increasingly described by historians as the “first genocide”… There’s a degree of ignorance and one expects of a museum in general, particularly one that has collections that were put together during the period, that it confronts these facts and declares what happened…

Focus on the profession of pedestal makers and installers around the works presented in the exhibition “20 years”. Dismantling of the exhibition. © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Léo Delafontaine

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: …to provide context!

Bernard Müller: Yes, and to remind people and highlight that in reality there were many contexts, without negating the fundamental brutality of the colonial act in general.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes, along with all its ambiguities, it’s a very complex phenomenon.

Bernard Müller: Ultimately though, the complexity of the colonial act, and its ambiguities, should neither soften nor trivialise the violence involved. There’s something to develop, a story of the defeated to be told, a story of the collection and its circumstances to be revealed. There’s a context to highlight and not only from the point of view of the collectors. It seems to me that this has yet to be done sufficiently. On several occasions, I’ve observed something that remains unresolved in this narrative, something frightening that so-called ethnographic museums have long preferred to put on hold, leaving history aside in favour of a cultural valorisation that is often somewhat abstract. It so happens that in 2006-2007, as assistant curator to Philippe Peltier, I took part in the implementation of the river, this central corridor that criss-crosses through the collections area of the MQB. Today, it’s dedicated to places but the original intention was to dedicate it to the history of the collections. This project has been reduced to the bare bones. That is, it was originally intended to be dedicated to this narrative that also included artistic interventions, but with a real mirror image of research with institutions, artists and oral traditions; something that is told from many points of view. There was then a fear, a reluctance to say “yes, let’s put it off, it’s going to awaken old demons”. The only part that remains is this small section with travellers and military doctors telling stories, which is engraved.

The River, the western part of the collection area, separating the Oceania and Asia collections.

Photo : Bernard Müller

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: A return to the historical context!

Bernard Müller: Yes, but is it enough? Don’t you feel that there’s a cap on colonial history that needs to be broken? In Germany, where a significant portion of the population are completely ignorant of the fact that Germany had a colonial empire, there was even talk of recurring to post-war methods in order to have the German population acknowledge its responsibilities. The idea of systematic school programs, compulsory excursions and film viewings have all been floated. With such an education it would be difficult to then claim “we didn’t know” or worse still; “people who complain about some sort of colonial humiliation are weaklings”. People can’t be allowed to go on saying these things! Of course contexts vary and it’s not black and white, far from it, but there needs to be access to this mechanism of subordination that was the colonial project, the racist foundations of colonial logic in the broadest sense.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Indeed, and it all rests on much older ideas that one would have great difficulty eradicating. But do people need to be forced? I don’t think so. I think they should be given the opportunity. With regards to research for example, we work with scholarships and the better part of them, the ones we finance that is, are directed toward collections, to their contexts. It could be considered anthropology, on the origin of objects or the history of objects. We’re currently creating scholarships in cooperation with the French National Library to enhance the value of archives that have been conserved but not yet identified. It will be interesting to see if there are any collections with key names. This is why we’re working simultaneously on the biographies of collectors because there’s a great deal of ignorance surrounding them. We’re also doing work on people who appear in photos because they’re strangely anonymous. When one searches a little, one realises one has the names but they’re just not on the same database. So there’s a great deal of work to be done internally on this matter, given that we previously separated all this information out. That is, we put the object in one place, the name of the collector in another and the context in which it was found in yet another.

Bernard Müller: Is it a methodological question then, of re-establishing the links between sources that have been separated from one another?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Methodologically yes, but you have to bear in mind that the fonds basically lived a life of their own, which is why its so difficult to track them down afterwards. The scholarships, as such, are now focused on these issues, we have a common scholarship on the memory of slavery that we’re actually launching with the foundation this afternoon, because its the same in this regard: why are there so few objects? We have very few objects that were collected in the context of slavery despite the fact it is a period of some considerable length; we have no collections on it. All in all, we’ve no more than fifty to a hundred objects, not including the images that is, only the actual objects. There are perhaps those for which information has been lost, which is altogether possible as we’ve been working on streamlining the inventories, joining one group of numbers to another and every year we find dozens of objects and give them back a lost identity. This happened at the beginning of the year with an object that was African for 200 years, we now know that it’s Tasmanian and from the 18th century. So you see, there’s a lot of work to be done in this regard. What’s important in terms of all this work involving research is to clarify the contexts as effectively as possible. The goal is to provide historical context for objects that are on permanent display. Indeed, we’re looking at the snake at the minute and wondering if it ought not be redone, so as to be an object of recontextualisation.

Bernard Müller: How are the collections impacted by the sort of research you envision? How does it fit in, not only with the temporary exhibitions, but with the permanent programming?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It has to be both. When we put together the exhibition “Kanak Art is a Word”[7] (MQB, 2013). I was quite determined that both of those aspects be fulfilled. That is, that the object be situated within its society as well as in its historical context. In other words, it doesn’t have the same meaning if it was taken from New Caledonia in 1878 as it would were taken in 1910. These are not the same types of relationship, the society in question is not at all in the same type of context. This is the kind of microsociology that is absolutely necessary. Hence the idea is to put the history back into this collection. The problem is that certain objects still remain silent, at least for the moment. Maybe one day, we’ll have methods to let them speak. The truth is that the technical methods available today give us access to information on objects because the objects can be their own source of information. It will never be a substitute for the context in which the object was produced of course. In spite of everything, we come to learn a lot about the physical make-up of an object. We were considering taking a series of objects from the four continents we’re interested in and about which we have adequate information. If we can’t do it for everywhere then better to do it for a number of places and in a very precise manner. For example, with those objects that can illustrate certain key points about France’s relationship with Oceania for example, or with the African or American continent, using a sort of survey that would ultimately be quite accurate. This is what allows us to say “here’s what you can do when you have all the information”. After that there’s a whole host of things that can go from nothing to their full capacity, and things can continue like that progressively. The difficulty with a museum is trying to offer people a breadth of information, to audiences that are themselves quite diverse, without completely killing the object. Today, you see, we have the means to do so.

Bernard Müller: So you would like to make this in-depth documentation available for a selection of objects along the river/the snake?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou : No, the idea was to rather to invest in the collection area and decide at which points on it there would suddenly be…

Bernard Müller: Lighting!

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Yes. You’re walking through Oceania and suddenly you have a whole series of objects waiting to give you the context. This is the real meaning. What happens at this or that moment in a particular country? It’s 1904 in Vanuatu, the French-English condominium has just been established, here’s what it means for people and here’s the story this object has to tell. So here we have an opportunity to be with the object and to then move from the object toward those territories and their historical contexts. You’re in Louisiana, its 1760, here’s what such and such an object has to say about the Natchez who disappeared some years later, here’s the story this object has to tell. Even in the case of Africa. The idea would be to extend this to every continent. Ultimately, what was done for Abomey will disappear so we have to find something in Africa that can contextualise things once again. The Dogon people in 1930 or the Djibouti map would be options. One should really be discussed through the other. It’s along these lines that our work is currently situated.

Bernard Müller: So there’s a historical inscription, in the collections area.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: The collections area, such as it is at the moment, is interesting in that it allows for a sort of walk, one that is quite free, through space and time. This utopia of being able to walk through space and time, I think that if a museum hopes to retain its magic… a museum is not an encyclopaedia, there needs be a lighter, more playful side. Now and again you have these hot spots of a sort whereby you can say “There you are, for whomever is interested, there’s a point of critical mass here to which you can recur.”

Bernard Müller: These hot spots should not become all-out confrontations of course.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Indeed, even if what we have to say is disagreeable, we have to say it. You have to state; this is how it happened, full stop. If you want to know more you can read this or look at that. There are a lot of possibilities today and, thanks to the internet, a lot of things we can get close to. We try to clarify the work we’re doing on an intellectual level too. Of course, it doesn’t reach the same audiences but; take the invitations on offer in the Jacques Kerache room, we gave free reign to Anne Lafont to explore a number of questions. This also enriches the way we can talk about objects. I don’t think a scenography is exhaustive, it’s simply an invitation to an intellectual and aesthetic voyage at a particular moment and I think it should remain an invitation to an aesthetic journey and to daydream. Again, I think there may be people who simply aren’t interested and who’ll use this kind of journey in forms and impressions for other ends.

Bernard Müller: But the message is not quite the same as it would be were it on permanent display so as to educate, in the widest sense, with an unavoidable space that evokes the context, that evokes the history behind the constitution of the collections, free to…

Emmanuel Kasarhérou : To be seen or not!

Bernard Müller: On another note; what are the internal stumbling blocks in research policy? That is, what internal conflicts exist between the existing approaches? Between art anthropologists and art historians, between post-modernists and structuralists? Do debates emerge that you find stimulating?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I don’t see any blockages. I find it interesting when people disagree.

Focus on the profession of pedestal makers and installers around the works presented in the exhibition “20 years ». © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Léo Delafontaine

Bernard Müller: Where are these knots to be found?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I have the impression, though perhaps it’s just my impression, that anthropology has changed sides. That is, rather than being on the side of communities, it takes the side of the dominant society and does not, as such, sufficiently nourish local points of view. History, on the other hand, at least in previous generations, was rather on the side of communities and valued distinct points of view. Whether this was right or wrong, it certainly seemed more interesting to me. These days, there are more people speaking on behalf of their own communities, and who criticize their own communities, which is also interesting. But there’s now nobody on the other side. I understand that this is difficult of course, but I do miss it. There are anthropologists for example, who would like to develop a space in which two gazes can confront one another but neither their training nor their fields are situated on the side of the society in question, or at least only weakly and so a certain return is lacking. People like the anthropologist Phillipe Descola have been there on the ground and thus they’re equipped with a radically different perspective. The new generations that I deal with, on the other hand, have weaker impressions and so it’s more difficult. It’s more difficult to find a point of contact for the Shuar. We’re trying to work with the bamilékés for example such that they explain their heritage in an exhibit we’re working on called “On the road to the chiefdoms”. It’s the bamilékés who then explain their heritage but because it was they that formed themselves, they’ve also formed their own museums. They’ve reflected on their past, what their heritage is and is not, what should and should not be valued. For a lot of communities however, more modest communities I was going to say, which are not necessarily chiefdoms nor do they have strong social organisation, or which are currently being completely torn apart or eliminated, we no longer have representatives we need, there’s no one to advocate on our behalf.

Bernard Müller: This is a serious problem in anthropology more generally, I completely agree. Anthropologists have lost their ground. Anthropology no longer takes the time for long-term research, whether in Europe or anywhere else in the world for that matter. The new rules of the game as brought in by the LMD reform mean that students tend to write their theses earlier and earlier and in an increasingly shorter time period. After which it’s just too late, because it’s more difficult to leave for a few months, let alone years, when you start a professional career or a family. Hence, the knowledge produced, even though it is the subject of academic publication, is not the result of sufficiently in-depth research, it may even be erroneous.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: One needs time yes, and consistency, that is, you need to remain on the ground for quite a while. It’s important for a confrontation between diverse forms of thinking to occur. And I feel that this is lacking, I see exhibition projects, for example, that seem too light. Hence, there’s a sort of cultural appropriation that I think is illegitimate because the object used is not embedded within a broader scheme. The scheme is instead projected and not at all similar to one that would come from a society. As such, there’s a form of instrumentalization and this is a real danger in my opinion. Though this may be because I’ve never worked with the right people and I’ve yet to identify the right people.

Bernard Müller: Fundamentally, we forget the essential part. To finish up, which are the most important meetings for you in the coming weeks and months?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: With the Covid crisis at the moment, it’s quite difficult to plan.

Bernard Müller: I’m not surprised!

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Things are a little vague at the moment but by some miracle and thanks to the team at the museum and the teams in Mexico, we’ve managed to open the exhibit The Olmecs And The Civilizations Of The Gulf Of Mexico[8]. It was a tour de force and the opportunity was quite unexpected I might add. I wasn’t overly optimistic a couple of months ago but we managed it and it’s quite impressive. We’re working from one day to the next somewhat. The same is true of the scholarship holders this year. Owing to the crisis we’ve had to extend their contracts so they can finish. It wouldn’t have been particularly nice to cut their stays by six months, a lot of them came from abroad as well. It’s a rather difficult period but the meetings will take place once we have the results of these projects and so for us it’s a question of this work and we’ll succeed in doing it. If one person among the teams becomes infected the entire floor has to go home, so it’s rather difficult.

Bernard Müller: It’s impossible, it’s quite simply impossible.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: On the other hand, I feel that internally there’s a real desire to work against this sensation, that is, to concentrate on investigating certainties. In the collections area for example, the fact that we’re not just looking at the issue of historical links but the type of information as well as the way in which it is transmitted. We saw that there was a particular way of reading the exhibit label too. So, we thought perhaps an introduction that explains what an exhibit label is would be necessary. What does it say? What does it not say? Where can we see what it doesn’t say? There’s a way of acknowledging the gaps in our knowledge. We opened an exhibition last year celebrating twenty years of the museum (“20 years. acquisitions” [9]) in which I systematically displayed the fact that the origin of certain objects was unknown. Normally we don’t display any information in this regard and so people suspect that we know but that we don’t state it. So, when we know, we say so and when we don’t, we have to admit that there are limits to our knowledge, that’s part of the game too. There’s also the question of how we speak about it if we want the museum to be open to as many people as possible. I’m also interested in reaching people that are referred to as being part of the diaspora, those who are second or third generation French and who may be interested in the culture of their originary families. Such families may go very far back and these may well be people for whom many other cultures are part of their identity. But it’s a question of finding accessible language. We’re all prisoners of our professional jargon. Typically, we’ll label something as “Ikebana”, full stop, and everybody’s supposed to know what an Ikebana is. We need to explain in greater detail and not simply depend on stock phrases such as ritual objects and so on. We need to examine our way of speaking about these things, both in terms of what we say and what we don’t say. We have to acknowledge the limits to our knowledge and, at the same time, revise the language that we do use. It’s something I’d like to do in conjunction with this work on labelling the objects but I’m not sure when we’ll manage to do it. There are these four points in the presentation that would relate to the four points of precise, historical contextualisation and which enable us to say “now you’ve seen the objects just floating around, don’t forget that they’re embedded within a particular historical context”; its colonial history. It might be that of the first French colonial empire in the case of Louisiana or Canada, or the colonial empires of the 19th century, it may be a mix of situations, it could be any number of different situations. You are, in fact, walking among the colonial empires of others. What struck me as interesting about the work that we did in cooperation with German museums and their « Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts » (published by the German Museums Association in 2018[10]) was that in actuality colonial meant domination. That is to say, we took all situations of domination and I thought to myself, it’s just in the background but it’s quite difficult in a way because there’s always domination. We’re living in a situation of domination right now; to this day there are kids digging in ditches so we can have batteries. Relations of power still exist, so where should we be hovering the cursor? Shouldn’t we be posing the question of domination more generally?

Bernard Müller: Well, what is the outlook for these boxes of historical perspective?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I wouldn’t know what to tell you, if I had everyone on hand right now…

Bernard Müller: Would you say it’s a priority?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s a priority for me because this part of the collections has always interested me and when we offer a collection that is essentially floating, we don’t do justice to the history of the objects. Of course, we can’t tell every story but they should be available to those who are interested. We also have a lot of information online to that end.

Foto report in the storerooms. March 2009. musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Cyril Zannettacci

Bernard Müller: What specific programme is the MQB developing for these audiences?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: There’s the work named nomad workshops example, which is very important and which has us in Aubervilliers at the minute. The United Nations is also in Aubervilliers of course, which is very interesting.

Bernard Müller: Is it enough?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s still a little weak and at any rate there’s a certain point beyond which we can’t extend the museum’s capacity any further. I wonder if it isn’t perhaps more judicious to be parsimonious and efficient rather than being expensive and inefficient. That is, doing too much and in the end achieving nothing. This is what we realised with the nomad workshop, if you reach 300 people you’ve done well as they’ll have privileged access.

Bernard Müller: And this will extend further of course, should they speak to others.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s a question of time at any rate. You can’t consolidate a cultural practice from one day to the next, it takes a great deal of time. We have this as a possibility as such but there will undoubtedly be others, we’ll experiment. Important work was done with the association of African women [11], which I think is very interesting as women are often more curious and inventive. They don’t hesitate to engage in new processes whereas men are a little more reticent I find. That’s been my experience of it at least. Perhaps I’m excessively rationalising but it was also my experience in New Caledonia. It’s easier to work with women than men as the latter tend to be more conservative in fact, at least in a situation of change such as that one. Alas, there’s work to be done. I intend on taking advantage of the fact that we’re currently working with Cameroon so as to float a number of test balloons with Cameroonian associations. After which, we need to find playing fields that are the same, because sometimes the communities have other ideas and the museum can be an opportunity for them at a particular moment, it’s not always necessarily an end unto itself. I was happy for us to host the exhibit Striking Iron from the Fowler museum, for which we received a visit from the federation of associations of Malian blacksmiths of Montreuil. They’d rented a bus to come see the exhibition and were thrilled with the techniques! The film that was part of it, I don’t know if you’ve seen the exhibition but it was very interesting, precisely because it dealt with techniques, models, tempering and so on. Those were the really interesting parts. Well, they were more like jewellers, they didn’t make ploughs any more.

Bernard Müller: Yes, because there is a Federation of African Blacksmiths and Artisans of Montreuil (FFAM)!

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: It’s terrific. I mean, we know that Montreuil is one of the biggest Malian agglomerations, but that’s why we have a federation of blacksmiths’ associations!

Bernard Müller: It’s fabulous.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I think they formed a federation as there would have been a number of different ethnic groups. Hence, each one would keep their identity in so far as they’d have their own association, even if there’s only two of them, it would be two from such and such a village. So I think that’s very interesting. Ideally, they would have liked to build a forge at the bottom of the museum so you could see them at work. Alas, it’s not always possible to do everything. Nevertheless, we still managed to spark quite an interest. We’ll have to see how things develop after that. Clearly though, there are techniques and know-how in circulation, as well as tastes that end up lasting much longer. As such, there is likely more work to be done yet. As for Cameroon, I don’t know much about the country but I’m going there next week. Here in France, Cameroonians are very well established, and in a variety of social strata; from labourers to university professors. Almost every level of society is represented. I can’t say if this includes all ethnicities that exist there or just a section of them but I see that the project of working with the Bamilékés really enjoins them. I have the impression it’s a means of existing too; of saying we are not simply heirs to a long and complicated history. There’s a need to express what happened during and after colonialism. All the more so at the moment given the current government, which is a curious one I have to say. At the same time, there’s a certain desire there and I’d like to see the museum position itself as a meeting place, even if those meetings are brief. This may be because there is a need at some point but it doesn’t endure. The fact is that the museum may be a place for expression of modern and contemporary culture at a particular moment. Above all, it shouldn’t freeze people with an attachment to the past even if we all have this feeling sometimes of “things were better before”, especially as we get older. The idea is distinct, we want to try and show that in light of all this and in relatively open contemporary societies, the museum is place of expression.

Bernard Müller: Perfect, thank you. We could go on all day really but at some point we have to stop.

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: I do like to talk yes.

Bernard Müller: I just need to take a photo. Could I ask Sylvie to take a photo of the two of us?

Emmanuel Kasarhérou: Fine, yes. Thank you.

Photo: Sylvie Camile

Footnotes

[1] Conducted on Thursday 15/10/2020

[2] On Gaëlle Beaujean’s work, see : http://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/expositions-evenements/au-musee/spectacles-fetes-et-evenements/rendez-vous-du-salon-de-lecture-jacques-kerchache-archive/actualite-de-ledition-et-de-la-recherche/details-de-levenement/e/lart-de-cour-dabomey-le-sens-des-objets-38359/

[3] The Dakar-Djibouti Mission is an ethnographic expedition conducted in Africa, under the direction of the ethnologist and air force pilot Marcel Griaule, from 1931 to 1933 that brought back more than 3,500 objects.

[4] The Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre (Centre culturel Tjibaou) opened in Nouméa (New Caledonia) in June 1998. It was named after the leader of the independence movement who was assassinated in 1989 and had had a vision of establishing a cultural centre which blended the linguistic and artistic heritage of the Kanak people (http://www.adck.nc).

[5] https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2020/10/13/gengis-khan-censure-par-la-chine-au-musee-d-histoire-de-nantes_6055866_3246.html

[6] https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2017/11/28/discours-demmanuel-macron-a-luniversite-de-ouagadougou

[7] https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/2013/10/14/nouvelle-caledonie-l-art-kanak-en-impose-paris-77233.html

[8] http://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/expositions-evenements/au-musee/expositions/details-de-levenement/e/les-olmeques-et-les-cultures-du-golfe-du-mexique-38518/

[9] “ http://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/collections/vie-des-collections/nouvelles-acquisitions/20-ans-les-acquisitions-du-musee-du-quai-branly-jacques-chirac/

[10] https://www.museumsbund.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/dmb-guidelines-colonial-context.pdf

[11]FECODEV is a platform of non-profit associations, created in 2005 in France by women from the African Diaspora : http://fecodev.org

[12]Louis Archinard (1850 -1932) was a French general of the Third Republic, who contributed to France’s colonial conquest of West Africa. He is often presented as the conqueror and peacemaker of French Sudan. An object of this type was also collected during the Dakar-Djibouti expedition