Provenance Research before Repatriation: The Limits of Museums’ Archives

DCNtR Debate #2. Thinking About the Archive & Provenance Research

As calls for cultural objects’ repatriations[1] are increasing and museums are being confronted with the colonial aspects of their collections and of the institution itself, one of the responses from the museum world is to highlight the need for research and documentation. The argument is that in order to know what to return, one needs to research provenance and how the artifacts came to enter the collections (Vikan, 2014; Förster, 2016; Hunt et al., 2018; Scorch, 2020). This way of proceeding is starting to be largely accepted as the first step of the repatriation process in Western museums, as shown for instance by the 4-year research program launched in 2021 by Belgian federal museums, coupled with a law on artifact repatriation[2] or the CROYAN research project at the French Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac Museum.[3] This movement is seeing an acceleration these last years, supported by society and political figures.[4]

This very legitimate approach raises the question of the limits of provenance documentation. What can we really learn from the archival records about the artifacts? And could we really use this documentation as a base for artifact repatriations? Using the example of a corpus of five French museums, this paper highlights the limits of archival documentation in the context of artifacts repatriations.

My doctoral project aimed at documenting the provenance of Pacific[5] collections (around 2500 artifacts)[6] in five museums in Northern France. Using records kept in museums, municipal and government archives, my goal was to trace the origin of the artifacts from their museum repositories to the countries of their makers.

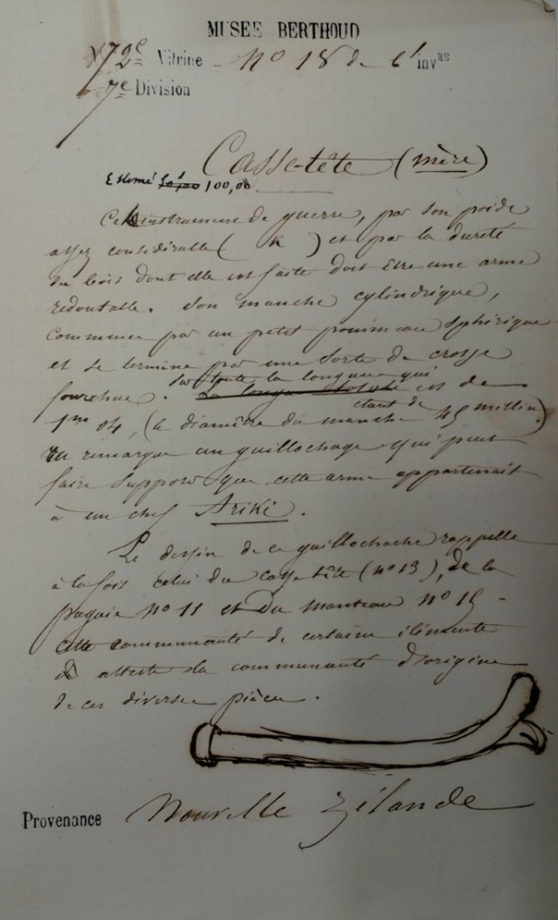

Fig.1: Inventory sheet n. 18, Massue, Aotearoa New Zealand, Archives of the Musée de la Chartreuse de Douai (photograph by Hoffmann)

1. What can we learn about who acquired the artifacts?

Although most of the donors were identifiable, the provenance trail often got cold past a few intermediaries (or even past the donor themselves[7]), and collectors could rarely be identified. In general, provenance research mainly provided information about the interpersonal connections, networks, and exchanges between notables of northern Europe (Belgium, England, France), which are, for the most part, irrelevant to repatriation issues.

In some cases, there is nothing to be learned from the archives. The most significant example in my corpus is the Natural History Museum in Lille. Its ethnographic collection is composed of around 13 000 objects from all around the world, defined by the Museum as “one of the richest ethnography collections in France”.[8] However, there are almost no archives documenting the collections as these were either lost or destroyed,[9] making it almost impossible to comprehend the context of acquisition for most of the artifacts. This case is unique in my corpus, yet the lack of records is a constant issue and questions the relevance of archival research when considering repatriations.

2. What can we learn about how the objects were acquired?

Despite the archival obstacles, it was possible to identify thirty-two collectors, even if the way they acquired the artifacts was seldom documented. However, the general context of their presence in the Pacific (a military expedition for instance) has provided important clues about the acquisition context. When available, the personality of the collector did also help to overcome the lack of data.

On the other hand, sometimes information available on the acquisition is balanced by the absence of the object itself. The counterpart to the Museum in Lille is the Berthoud Museum in Douai. Its archives are almost totally intact, with minutes of the ethnographic commission, correspondences, catalogs, etc. This documentation even includes very specific artifacts provenance clearly identifying some artifacts as colonial war trophies. However, the Museum itself was bombed on August 11th, 1944, and 30 000 artifacts from the Berthoud Museum (including 1 122 from the Pacific area) are presumed to be destroyed, making any repatriation impossible.

3. What can we learn about the indigenous perspectives?

If data on the acquisition is rare, the absence of indigenous perspective in the archives is glaring. Museum collections documentation is mainly composed of collecting instructions, catalogs, and classifications: colonial tools that were used to organize the world through a western lens (Philips, 2011; Gibson, 2020; Turner, 2020). Considering that these documents emanated from colonial entities, indigenous points of view are therefore absent. Even in the notes of the collectors, if they still exist, the makers of the artifacts are almost never mentioned, rendering them completely invisible. The lack of written indigenous perspectives can be helped by oral traditions, hence the necessity of collaborations with the societies which produced the artifacts. Such a partnership exists for only one of the institutions I’ve studied: the Boulogne-Sur-Mer museum has been working with the Sugpiat people in Kodiak (Alaska) since 2002 (Salabelle et al., 2018).

Based on this research, we can conclude that the idea that provenance research is a necessary step of the repatriation process is biased. Archival research may provide some useful context when considering restitution, but even when there is information to be found, it is at best insufficient and at worst reinforces colonial power imbalances. Establishing contact with the makers’ communities and hearing their voices appears more important than perusing the archives. In fact, the way the artifacts were acquired might not be as crucial as the current heritage situation in these communities: can we legitimize the fact that former colonies’ heritage would be mainly in the custody of Western museums?

Marie Hoffmann holds a Ph.D. in Museum Studies and holds the position of Associate Researcher at University of Lille, CNRS, UMR 8529 – IRHiS – Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion. Her reseach areas include the history of collections and collectors, the history of anthropology and ethnography and artifacts provenance research.

Footnotes

[1] In this paper, the word “repatriation” will be preferred to “restitution”.

[2]https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1277051/culture/rdc-belgique-des-repatriations-doeuvres-dart-mais-pas-tout-de-suite/

[3] https://croyan.quaibranly.fr/en/the-project

[4] Including the Sarr-Savoy report commissioned by the President Emmanuel Macron and published in 2018 (Sarr & Savoy, 2018).

[5] An inventory of Pacific collections in French museums was done between the 1940s and the 1990s which identified the geographical provenance of the artifacts.

[6] This paper will not consider human remains: no matter how they might have been “acquired”, human remains can not be treated as objects and their repatriation can not be placed on the same level as artifacts.

[7] Among the 95 donors identified, only 8 were women.

[8] https://mhn.lille.fr/la-collection-ethnographie

[9] This fits with the collections history: the artifacts were exhibited only 67 years between the museum’s creation in 1851 and the transfer of the collections to the Natural History Museum in 1990.

References

Förster, L. (2016). Plea for a more systematic, comparative, international and long-term approach to restitution, provenance research and the historiography of collections. Museumskunde, 81(1), 49-54.

Gibson, L.K. (2020). “Pots, belts, and medicine containers: Challenging colonial-era categories and classifications in the digital age.” Journal of Cultural Management and Cultural Policy/Zeitschrift für Kulturmanagement und Kulturpolitik 6.2 : 77-106.

Hunt, T., Dorgerloh, H., & Thomas, N. (2018). Restitution Report: museum directors respond. The Art Newspaper, 27.

Phillips, R. B. (2011). Museum Pieces: Toward the Indigenization of Canadian Museums. Montreal and Kingston:McGill-Queens University Press.

Salabelle, M.-A., Alix, C. & McLain, A. Y. (2018). Deux musées pour un héritage : Les collections unangax̂ de l’île d’Unga. Études Inuit Studies, 42(1-2), 179–207. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064501ar

Sarr, F., & Savoy, B. (2018). Restituer le patrimoine africain. Philipe Rey/Seuil.

Saussol, A. (1979). L’héritage: Essai sur le problème foncier mélanésien en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Société des Océanistes. doi:10.4000/books.sdo.563.

Schorch, P. (2020). Sensitive Heritage: Ethnographic Museums, Provenance Research and the Potentialities of repatriations. Museum & Society, 18(1), 1-5.

Stumpe, L.H. (2005). Restitution or repatriation? The story of some New Zealand Māori human remains. Journal of Museum Ethnography, No. 17, Pacific Ethnography, Politics and Museums, 130-140.

Turner, H. (2020). Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. UBC Press.

Vikan, G. (2014). Provenance Research and Unprovenanced Cultural Property. Collections, 10(3), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/155019061401000313.