Empirical notes on the exhibition “L’Un et l’Autre” (One and the Other)

Palais de Tokyo, Paris 2018

“It is so much easier if you are an art museum!”[1]

In the framework of the conference Exchanging perspectives: anthropologies, museum collections and colonial legacies between Paris and Berlin[2], I was asked to give an overview on the institutional changes of Parisian art museums with regard to colonial history.

Indeed, I could have mentioned several shows that have been presented during the last months in the city such as the current exhibitions by Bouchra Khalili or Daphnée Le Sergent at the Musée du Jeu de Paume, the Belgian artist Vincent Meessen or the South African artist David Goldblatt at the Centre Pompidou, Mohammed Bourouissa at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Black Dolls at la Maison Rouge, Julien Creuzet at Béton Salon and the project Practising colonial images – Propaganda films and private archives at the pluri-disciplinary art space Khiasma. All these projects are differently connected with colonial history. It would thus be worth to look at each of them systematically and precisely in order to observe the various ways in which art institutions in Paris today are confronted by (and confront themselves) the colonial pasts and its current resonances.

Yet, I will very modestly focus on one particular moment, namely the exhibition curated by the two internationally well-known artists Kader Attia and Jean-Jacques Lebel at the Palais de Tokyo (February − May 2018). This exhibition proposed to dismantle the “ethnological” construction of the “Other” through different contemporary artistic contributions.

What could the “ethnological” mean in this context? I may refer here to Sharon Macdonald who defines the term as follows: “Putting it briefly, the ethnological was formed by scholars and travelers through their encounter with peoples and life-ways perceived as different from those with which they were familiar or that they classified as part of their ‘own’ histories. […] As such, the ethnological was predicated upon a distinction between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, or what critique in the later twentieth century came to be referred to as between ‘the Self’ and ‘the Other’– with the ethnological dedicated to ‘the Other’”[3].

The exhibition echoes the quite widespread conception that contemporary art constitutes the best place to critique the “ethnological”: “L’Un et l’Autre [One and the Other] is an exhibition born from the harmony between our energies. Together, we present a selection of our work that deals with the major issues of our civilization – a civilization that considers itself, incorrectly, as a ‘postcolonial’” one – alongside a heterogeneous ensemble of works of art, films, texts, music and objects. In doing so, we have brought together fellow artists whose approaches intersect with our owns, as well as objects collected in the course of our research; we have disregarded their ‘value’ or their authorship in favor of their ultimate destination, their symbolic mode of functioning.”[4] The curatorial project of both artists is thus based on a critique of colonial history and its contemporary echoes. One aspect of the colonial heritage that the artists want to point out and deconstruct is based on the fact that artifacts that are commonly studied or exhibited for historical and or ethnological interest. Instead, Lebel and Attia want to focus on their “symbolic mode”; they believe that through their artistic approach it might become possible to consider a common human being: “Everywhere and at times unknowingly, their creators have, like us, practiced an art of détournement and of réparation.”[5] Both concepts, “détournement” and “réparation”[6] constitute the narratives that is supposed to help the visitor to get different view on objects that are commonly classified as ethnographic or folkloric. Insofar, One and the Other does explicitly refer to the “ethnological” construction by which human societies were frizzed into two distinct entities and the artists aim is to overcome a dichotomist perception.

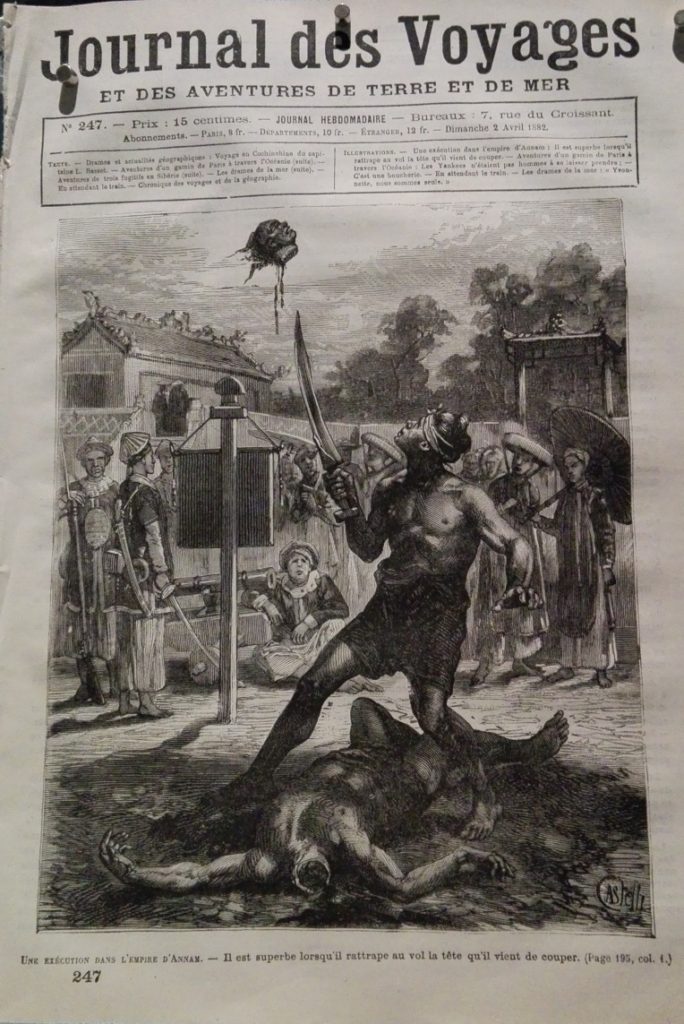

In this contribution, I will discuss some of the discursive and curatorial gestures of the exhibition. My aim is to look critically at the conception of “art” that is – if we follow the artists – supposed to deconstruct the “ethnological”. Furthermore, I will ask whether “art” may actually be a “privileged” critical space, in which – what both authors denounce as colonial or “ethnological” – could be deconstructed. All art works in the show gravitate around the two main installations of Kader Attia and Jean-Jacques Lebel. The first, entitled The culture of fear: an invention of evil (2013), presents a collection of documents − newspapers, books, posters arranged on the shelves of a library. As can be read in the exhibition text, the installation tackles the role of the media in the production of categories of fear like the figures of Satan, the savage and the terrorist. For Attia, these images produce the figure of the “Other” which is associated with images of a dark and brutal savage that constitutes the alter ego of the modern white man.

Captures 1-5: View of the installation The culture of fear: an invention of evil (2013) by Kader Attia, presented in One and the Other, Palais de Tokyo, 2018

©Photo Anna Seiderer.

Lebel’s installation, echoing Attias’, is conceived as a labyrinth of images taken in the Abu Ghraib prison by American soldiers. The visitor is trapped in a sufficing space of horror: “Some will say that it is obscene, but there is nothing pornographic in my approach, I recontextualize and I say what I have to say. Faces and sexes are blurred in photos taken in Abu Ghraib by American soldiers but the most obscene thing of all, torture, is not censored.”[7] Lebel’s installation plays in a provocative way with the censorship exerted in the name of justice and morality.

However, the fact that he responds to the obscenity in terms of pornography is quite interesting: He deliberately ignores the huge critique one could address to his work in terms of obscenity as he repeats the violence of those images by reproducing them and by imposing them to the public.

Captures 6-8: View of the installation Poison soluble. Scènes de l’occupation américaine (Bagdad. 2013) by Jean-Jacques Lebel, presented in One and the Other, Palais de Tokyo, 2018

©Photo Anna Seiderer.

This might confirm that artistic institutions enjoy their exceptional status or that they deliberately allow the controversies that artistic proposals may provoke. It may be interesting to imagine the reception of the above described artworks in an ethnological museum – especially as today, one of the major difficulty and critique they are facing is based on the argument that they repeat the historical violence by its presentation. There are several examples of images and objects banished from exhibitions and catalogues in the name of respect and moral integrity. The censorship applied nowadays with regard to contested historical documents or representations is a huge matter of discussion that I cannot retrace in this contribution. Yet, I note that Lebel argues that he challenges social and moral conventions, which he denounces as being hypocritical. He speaks about the violence perpetrated by those who censor, namely the media hiding the genitals of prisoners without questioning the structural violence of the images as such. In this regard, he indirectly engages in a discussion with Attias’ installation in which the violence appears as being inherent to the representations perpetrated by media from the pre-colonial period until today. Attia presents newspaper covers and books that play with stereotypes of “the Other”, like pictures of Bin Laden or of terrorist attacks.

I may note here a fundamental distinction of both conceptions of images that in my view radically change their artistic gestures. In Lebel’s work the violence is not inherent to the image but in what Arjun Appadurai would call its “social life”[8]. The violence of the Abu Ghraib pictures is less due to the fact that one sees tortured bodies. The photographs are rather violent because soldiers are staged in front of those dehumanized bodies – and they are especially controversial because of the hypocrite moral precautions to hide genital parts of the bodies. For Lebel, the violence is not inherent to the image but become violent by its context and uses. In the Abu Ghraib case, the pictures are an opportunity to claim moral values of a puritan society. It is precisely this puritanism that the artist challenges in his installation. Attia’s project rather seems to identify the violence of the “ethnological” as a matter of representations as such.

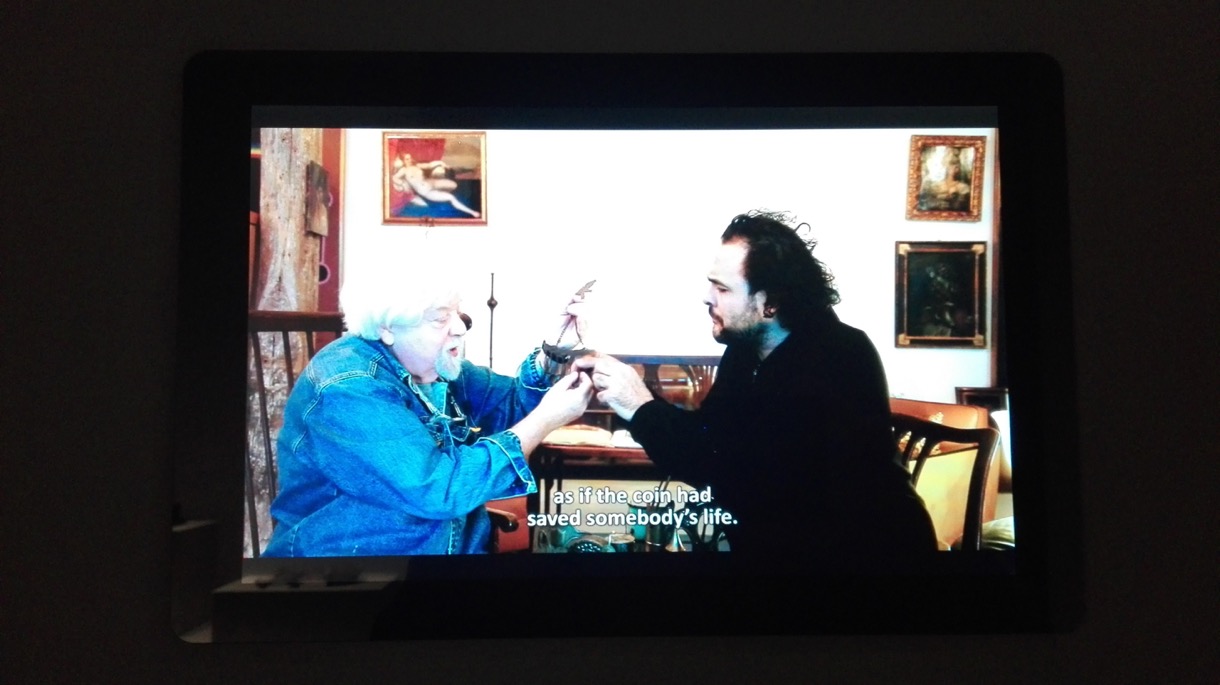

When I visited the exhibition, my concern was to understand the efficiency of their aesthetical language with regard to the questions both artists tackle in each installation as well as in the overarching curatorial concept. I may add that Lebel and Attia invited several contemporary artists[9] as well as they presented works by “anonymous artists” from their private collections; the latter were artworks that are commonly referred to as ethnographic or folkloric. The works by the “anonymous artists” were presented in showcases in the form of houses that the public could enter. Drawings representing objects and notes on subjective impressions by Kader Attia and Jean-Jacques Lebel were presented on labels fixed to the walls close to the showcases. A couple of screens presented both artists, sitting one in front to another, commenting each object.

Capture 9: Video capture by Kader Attia and Jean-Jacques Lebel commenting on an object in the “anonymous artists” category presented in the exhibition One and the Other, Palais de Tokyo, 2018 ©Photo Anna Seiderer.

Capture 9: Video capture by Kader Attia and Jean-Jacques Lebel commenting on an object in the “anonymous artists” category presented in the exhibition One and the Other, Palais de Tokyo, 2018 ©Photo Anna Seiderer.

In contrast to the presentation in ethnological museums, the objects here are disconnected from any attempt to provide a scientific discourse. On the contrary, they are presented for their aesthetic, affective or intriguing aspects or stories. While visiting the exhibition, I met a very enthusiastic colleague who told me that the artistic language should be understood as standing for itself and needs to be preserved from any political and economic contexts. This modernist conception of “l’art pour l’art” seemed to be considerably in contradiction with the actual aim of the exhibition to engage in a complex political discussion about colonial legacy.

The aesthetical language of this exhibition is built on the dichotomy of the “We” versus the “Other”; in other words, the colonial mode of difference that the exhibition actually wanted to dismantle by showing its genealogies and manipulations. However, the way the artists speak in the name of the so-called “anonymous artists” − instituting themselves as the voices of those anonymous and voiceless “Others” − are in my opinion quite problematic as the artists’ subjectivities and personal biographies provide the only framework to understand the exhibition and its objects. Finally, this particular example brings me to question the “privileged space” of art institutions that is supposed to challenge the “ethnological” − as far as it paradoxically seems to dime its critical scope.

Anna Seiderer is PhD in aesthetic. She studied the concept of transmission at work in “postcolonial” museums in Benin before working as a researcher in the ethnography division of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren from 2008 to 2015. She is currently Lecturer in Contemporary Art and Anthropology at the University of Paris 8. Her research interests focus on the visual anthropology of colonial images and the paradigm of the “artist in ethnography”. Her work aims to explore the artistic forms and epistemological constructions that emerge from the encounter between contemporary art and anthropology.

––––

[1] Curator of the Humboldt Lab Dahlem quoted by Sharon Macdonald in “The trouble with the ethnological” in The Laboratory Concept. Museum Experiments in the Humboldt Lab Dahlem. Berlin: Kulturstiftung des Bundes, p. 211.

[2] Conference organized by Felicity Bodenstein and Margareta von Oswald in the frame of the CIERA project “France et Allemagne face aux héritages coloniaux: relectres contemporaines des collections de muse (musée?)”, 2017−2019.

[3] Macdonald in “The trouble with the ethnological”, op.cit., p. 212.

[4] Exhibition text signed by Lebel and Attia.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The terms cannot be translated into English.

[7] Jean-Jacques Lebel, exhibition text.

[8] Arjun Appadurai (ed.) The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

[9] Marwa Arsanios, Sammy Baloji, Alex Burke, Gonçalo Mabunda, Driss Ouadahi, Perou- Pôle d’exploration des ressources urbaines.