Decolonisation? Collaboration!

Towards a Renewed Concept of ‘Museum’ in Europe and Africa

What options do we have for dealing with the Africa collections in our museums in Europe and in Africa? Let us start with a quote from Malcolm McLeod, keeper of the Department of Ethnography of the British Museum from 1974-1990:

Museums are expected to collect things, yet museum collecting, in some cultures, need not be a good or useful activity – it may even be an extremely bad thing, something which helps to destroy a culture instead of helping to preserve it. A new museum commissioned, created and paid for by the people whose culture and history it represents provides an interesting example of this phenomenon. The museum is one in which collections and collecting play a very small part. Its creation and initial success draw attention to the fact that some cultures have ways of preserving and displaying their past which need not involve the formation of museum collections.[1]

What do we mean when we speak of ‘decolonisation’? What does this term encompass, and what does it entail? The concept of ‘decolonisation’ still needs a closer look. We want to show that the lately frequent calls and attempts for ‘decolonisation’ have as their corollary an opening up of museums and collections. Decolonisation is necessarily linked to cooperation with external interest groups. Now, are options of the often-invoked circulation of objects, long-term loans and just different forms of cooperation anything more than excuses and subterfuges to avoid restitution? The question remains open and has to be examined on a case-by-case basis. We believe that all these options must complement each other. Museum collections have to be set in motion today.

Decolonisation cannot be reduced to a simple return of artefacts or whole collections. As a necessary concomitant, it has to be accompanied by reconsidering and questioning the procedures and the very fact of collecting: what are the reasons for and the origins of the respective museum’s collections? Why and how were these objects assembled? What kind of information and knowledge have been recorded and circulated? This again implies rethinking the structures and the ways of functioning of ethnological collections and museums in general. It means scrutinising the very concept of the ethnographic / ethnological as a cultural history museum.

In recent years, there has been increasingly talk of cooperating with and involving originating communities in the work of museums in the Global North. We are firstly confronted with the difficulty that there are not necessarily such ‘communities of provenance’ we could work with and that would qualify as communities. For this reason, we favour to employ the term ‘societies’ or even ‘regions of provenance’. And we prefer to get in touch – and, in the best case, partner – with local institutions or bodies that have an interest in our collections and museum activities. For museums, the most obvious counterparts are not always, but in many cases museums rather than the often-invoked alleged (local) communities of origin. Here we would like to present and discuss an example of such a partnership. We explore from a Swiss and a Ugandan point of view the case of a tripartite long-term collaboration between museums in Uganda and Switzerland, a partnership started in 2015 that centres on reciprocal ethnographic research undertaken in both countries. It involves an exchange of knowledge about museum practice and has so far resulted in diverse exhibitions, seminars and publications, among other things.[2] It is an experiment in and an effort for a partnership on equal footing, despite being framed by structural inequalities.

Illustratioan 1 & 2: Mobile Milk Museum, Eastern Uganda, March 2019, Photos: Ali Nkwasibwe © Uganda National Museum

Before we give a broad outline of our example, we want to briefly sketch the current situation of ethnographic museums in Europe and in Africa and then to discuss alternative options in dealing with objects as parts of museum collections. To start with, it would be simplistic to say that ethnological museums are in crisis today. However, if we want to understand ‘crisis‘ in the original literal sense as a ‘decisive turn‘, then there definitely are aspects of such a change. In any case, ethnological museums today are in a period of upheaval and find themselves suddenly in the centre of new, previously unknown attention. However, their situation is not simply a critical one, but one characterized by new energy and dynamism that have not been seen for a long time. And this applies to museums in Europe as well as in Africa. Something has started to move, and this movement can no longer be stopped. The new dynamic will also have consequences for the handling of the collections for which a new dynamic, new motion is sought, just as the title of this conference says.

In discussing issues of property and restitution and related strategies, we can easily get the impression that the concerned museum practitioners and politicians are preoccupied almost exclusively with Europe and the Global North. The other side, in our case Africa, is hardly ever discussed. Furthermore, we rarely hear the voices and opinions from the African side. Actually, when addressing issues of possible returns and property, we would expect more attention to and engagement with the receiving, that is the new hosting side, as the original starting point of the collections, and not only with the now outgoing, returning body. With such a shift of focus, turning our attention not only to the outbound, but also to the inbound side, the debates receive a new weighting and orientation. We are convinced that they can bring about and materialise in new possible solutions.

In addition to ‘local communities‘, cultural and museum institutions that may have been involved in the process of collecting and assembling the collections in Africa would thus need to be considered. Museums in Africa have found new attention and dynamism in the last two years, certainly also stimulated by the international debates on cultural heritage and restitution. The recent relaunch of AFRICOM, the International Council of African Museums, is an expression of the new drive and debate in the cultural and museum landscape on the African continent. This relaunch was announced just last May on the eve of the “International Museum Day” organized by the International Council of Museums (ICOM), this year under the motto “Museums as Cultural Hubs: The Future of Tradition”. This pan-African non-governmental organisation, founded in 1999 in Lusaka, Zambia, had fallen asleep after its first successful years of capacity building and networking among African museums and was no longer functional. The AFRICOM renaissance is an encouraging signal, promising new impetus and a multilateral basis for stronger networking among African museums and beyond. But it will not suffice by itself. There is a need for new multilateral initiatives and procedures. European museums and cultural institutions should look beyond a purely bilateral pattern of action and be ready to actively involve African bodies and umbrella organisations. This is a necessary condition for their success.

The new attention to African museums also revealed the widespread biased and skewed perception of museums in Africa. It surely is futile to make generalisations for the whole (sub-) continent, but we clearly can identify some distinct common characteristics that make museums in Africa stand out from museums in the northern hemisphere. This is not surprising when we consider the noticeably different social and political position of most museums in today’s contemporary societies of sub-Saharan Africa.

Illustratioan 3: Igongo Cultural Centre, Mbarara. Photo: Ali Nkwasibwe © Igongo Cultural Institute

Many cultural history museums in Africa are still faced with the underlying problem that they are creations of the colonial era. But, contrary to what is sometimes described cursorily, most of today’s museums in Africa are not just dusty places of colonial history and collections, mostly assembled by Europeans and appearing strange on site. This was recently pointed out by several scholars who know today’s African museums from their own experience (e.g. Schrenk 2019, Schwere 2019). The concept of the museum has undergone a fundamental change of meaning in Africa in recent years. A new generation of scholars and museum practitioners has begun to reappraise these places dedicated to cultural heritage and to provide and use them with new directions and functionalities. In their tasks of identity-strengthening (be it on a national, regional or local level) and of the formation of social and socio-political responsibility and interest, they contribute to the integration of and dialogue with local communities, as well as to the international production of knowledge. The associated strands of knowledge are decisive for the broad acceptance of all levels of the objects’ meaning and for their reconnection to the population groups involved, in whatever form.

Many museums in Africa are now characterised by a greater breadth of social tasks and functions. They are more places of encounter and confrontation than of contemplation and aesthetic enjoyment. They radiate and are oriented more outwardly than inwardly. In many cases, they have broad-based outreach programmes and regional outposts, sometimes specialised like archaeological sites. This gives them a stronger local aura and impact, in accordance with specific interests and local requirements.

All this applies independently and despite often inadequate infrastructure. An out-dated infrastructure does not fundamentally hinder the primarily externally oriented tasks. The use of the available funds expresses cultural-political priorities: buildings and their shells are less expected to be architecturally iconic and technically highly equipped, than to engage in outreach and have broad impact. The point is an active exchange with a broad public in various forms and direct dialogue and debate, up to participation in processes of conflict resolution and reconciliation.

Illustratioan 4: The Uganda National Museum, Kampala. Photo: Melanie de Visser © Uganda National Museum.

It is not surprising that the various museum models can also be associated with a different use of the museum’s collections and different application and handling of the objects. As we have seen from our Swiss-Ugandan partnership, and it is not the only one, such intercontinental relations and professional exchange through museum work can provide a new access to the collections and the broader material world of objects not necessarily stored in museums. In order to arrive at new approaches to museum work and dealing with collections, a certain ‘démusealisation’ may be necessary, as Germain Loumpet uses the term – to move away from and liberate ourselves from former conceptions of dealing with and viewing collections shaped too much, even dictated, by European practice. “The difficulty lies in reconciling established museographic obligations with the requirement for participation. It is not enough to simply propose a display; the actors – who are, at the same time, the subjects and objects of their own history – must also be present” (Loumpet 2018:46). Or as another colleague from an African museum association put it: “Today we are reviewing the role of museums [in Africa] – we need a shift from conservation to cooperation and communication.”[3]

Which options of working with objects from museum collections are there today?

- First there is the continuation of the status quo – collections and objects remain largely in storage, only 2% – 5% can be seen and are accessible in exhibitions. At this point, we have to be aware that the original owners or originators of the collections usually cannot trace where the objects are located. Indigenous people’s attempts to enquire are often bureaucratised through formal proceedings that are far beyond the level of possible engagement of the rural population.

- All possibly reclaimed objects are returned to their originators or original owners. Today it is generally understood that in most cases a return cannot mean just filling an empty space in a drawer or cupboard (that in most cases doesn’t exist), closing and ‘healing’ a wound. As we have learned from many and also the latest examples of restitution, each is linked to numerous questions that still have to find answers. Furthermore, the public’s level of awareness and involvement in the topics of restitution or the politics of restituting ‘African Art’ is yet to be understood. Considering the spirituality of the objects, were they taken from museums or from the communities? What is the process of returning these objects, what forms of agency become involved in the specific restitution procedure?

In the vast majority of cases, the politics and ethics of returns are determined by the fact that they take place through official channels. In the coming years, they will continue to be a constituent part of the state’s cultural policy that shapes the discussion of returning African art. Restituted artefacts are usually received by official state museum institutions. It has to be seen here that it was precisely this type of colonially established museum that was responsible for some of the cruelty and atrocities done to the objects. This calls into question these museums’ suitability and their entitlement to receive objects returned by the successor states of the former colonial powers and to act as recipients of the restituted objects. This is only one of the complex considerations and questions linked to any return. - There are other options for dealing with objects from museum collections besides keeping them untouched and preserving them as long as possible in the state in which they entered the museum. “The museum is not a prison for the objects. They can come and leave again,” explained Raymond Asombong, the director of Cameroon’s National Museum at a conference held in Yaounde at the beginning of July 2019.[4] Many times, important objects are only loans to the museum from the communities, and they are regularly taken out to be used in (political, spiritual, religious) functions and ceremonies, which sometimes also take place at the museum itself (e.g. of the Manhyia Palace Museum of the Asantehene in Kumasi, Ghana, the Uganda Museum in Kampala, the Palace Museum of the Sultan of Bamun in Foumban, Western Cameroon etc.). In this regard, one sometimes speaks of a “living museum”, “un musée vivant” where the boundaries between museum, environment and originators are more fluid than we are familiar with in the West (in other cases, for instance in southern Africa, the label ‘living museum’ is given rather to museum sites where local artisans and craftspeople perform for the audience).

As a subcategory of such practices, we can see the cases of objects that are used and employed by the communities or by the museum in contact with the communities, for instance in procedures of conflict resolution and reconciliation (see Abiti’s example from Northern Uganda or others from Kenya). - Replicas are another option. Here we should first recall the questionable quality of ‘authenticity’ and that in African societies many major spiritual, quasi-sacred or dynastic objects were regularly replicated. This was also the solution found for the exhibition in Kumasi’s palace museum, where it was decided that further replicas should be made for displaying whereas the existing ones can still be used as ‘working objects’ to perform some function in the continuing operation of the social, religious and political system.[5] As the objects could be useful or used by more than one party, if reclaimed or not, museum practitioners should envisage working with replicas, which nowadays can be manufactured quite easily by digital tools. As a general rule, we postulate that it goes without saying that the ‘original’ – if such exists – goes to the originators and the replicas to the museums.

- In some cases, there is the option of using the collections, as small and fragmentary as they may be, to establish new relations between museums, as in the case of the Swiss-Ugandan partnership, or between museums and communities, integrating different forms of knowledge production.

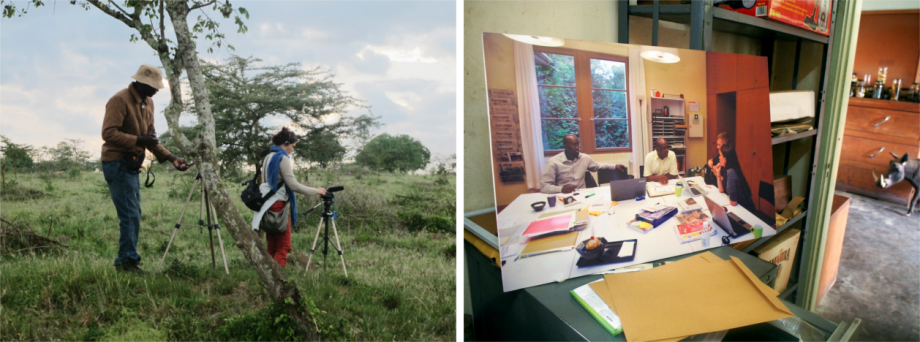

Illustration 5: Fieldwork in Western Uganda, April 2017. Photo: Carolina Cerbaro. © Ethnographic Museum at the University of Zurich. — Illustration 6: Photo of a team meeting in Zurich (2015) displayed in the office of the natural history curator at the Uganda Museum. Photo: Thomas Laely, © Ethnographic Museum at the University of Zurich.

What we need today is a new way and form of relating to and dealing with objects and collections. As we have tried to point out, there are several options and new ways open to value and enhance the museum collections in and between Africa, Europe and beyond when we dare to question the paths, values and ways of acting that have been followed predominantly up to now, and at times leave these paths for new routes. In the process, cooperation and networking are a central part of a newly conceived museum that is ready and able to accept and take up postcolonial challenges both in Europe and in Africa.

Thomas Laely is a cultural anthropologist with a focus on museology, political anthropology and African studies. He has been the Deputy Director of the Ethnographic Museum at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, from 2010 to 2019. In previous years he was active in international arts promotion, 1994 – 2010, establishing and directing the International Department of the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia. Currently, Laely is concentrating on issues of the history and perspectives of ethnological museums, particularly the exploration of new practices of collaboration between cultural history museums in Europe and Africa.

Recent publications

2019 Towards Mutuality in International Museum Cooperation: Reflections on a Swiss-Ugandan cooperative museum project, with Marc Meyer, Amon Mugume, Raphael Schwere. In: Stedelijk Studies 9, issue summer 2019, Amsterdam.

2018 Museum Cooperation between Africa and Europe. A New Field for Museum Studies, with Marc Meyer & Raphael Schwere (eds.). Bielefeld & Kampala: transcript-Verlag & Fountain Publishers, 242 p.

2017 Das Museum als ethnologische Methode? Zeitgeschuldete Betrachtungen. In: Hahn, Hans-Peter (Hrg). Ethnolo und Weltkulturenmuseum. Positionen für eine offene Weltsicht, pp. 175-219, Berlin: Vergangenheitsverlag.

2016 Collecting, Revisiting, Reappraising – Restituting? The Schinz Collection of the Ethnographic Museum at the University of Zurich. In: Collet, Dominik, Füssel, Marian & Roy MacLeod (eds). The University of Things. Theory – History – Practice, pp. 57-70. Jahrbuch für Europäische Wissenschaftskultur, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Vlg.

Nelson Adebo Abiti is the curator of ethnography at the Uganda National Museum. He holds an MA from the University of East Anglia (2015), received his Bachelor’s degree from Makerere University (2003) and studied for a Diploma in Museums and Heritage Studies at the University of Western Cape, South Africa. From 2010 to 2013, Abiti headed a team of Uganda National Museum staff and Norwegian partners, who collaborated with several communities in northern Uganda to preserve and present the regional memory and, thereby, promote peace and reconciliation following a long civil war. The result of this cooperation was an exhibition entitled Road to Reconciliation. Currently, Abiti is working with the committee that revises Uganda’s museums and monuments policy and legislation, and has been a core team member of the cooperation project between the Uganda National Museum, Igongo Cultural Centre and Ethnographic Museum at the University of Zurich, which is jointly curating exhibitions in Uganda and Switzerland since 2015.

Footnotes

[1] McLeod, Malcolm, “Museums without collections: museum philosophy in West Africa”, 2013:52f.

[2] Two exhibitions on Ugandan and Swiss milk cultures were launched in September 2017 in Kampala (Drink Deeply!, until May 2018) and Mbarara (The Power of Milk, now part of the permanent exhibition); the exhibition Points of View: Visions of a Museum Partnership, also providing a virtual tour through two exhibitions in Uganda, was displayed at the Museum in Zurich from April 2018 until January 2019. The subsequent Mobile Milk Museum was touring Uganda’s regions on a large truck with an extendable exhibition space from February to July 2019.

[3] Jeremy Silvester, Museum Association of Namibia, at the workshop ‘Stolen from Africa?’, Basel, 8 May 2019.

[4] “Nouveaux Modes de Coopération muséale entre l’Afrique et l’Europe: le cas du Caméroun et de la Suisse”, Institut Français du Caméroun, Yaounde, 4 juillet 2019.

[5] Cf. McLeod 2013:58.

References

Abiti Adebo, Nelson. 2018. The Road to Reconciliation. Museum Practice, Community Memorials and Collaborations in Uganda. In: Laely, Thomas, Marc Meyer and Raphael Schwere (eds.). Museum Cooperation between Africa and Europe. A New Field for Museum Studies. Bielefeld & Kampala: transcript-Verlag & Fountain Publishers, pp. 83-95. DOI: 10.14361/9783839443811-008Loumpet, Germain. 2018. Cooperation between European and African Museums: A Paradigm for Démuséalisation? In: Laely, Thomas, Marc Meyer and Raphael Schwere (eds.). Museum Cooperation between Africa and Europe. A New Field for Museum Studies. Bielefeld & Kampala: transcript-Verlag & Fountain Publishers, pp. 43-54. DOI: 10.14361/9783839443811-008

McLeod, Malcolm. 2013 [12004]. Museums without collections: museum philosophy in West Africa. In: Knell, Simon J. (ed.). Museums and the future of collecting, pp. 52-61. Farnham: Ashgate Publ.

Schrenk, Friedemann. 2019. Afrikas Erbe: Wir müssen verhandeln! In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 30.04.2019.

Schwere, Raphael. 2019. Afrikas Museen haben sich längst emanzipiert. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 17.04.2019.