A Look into the Vienna Weltmuseum

The relaunched Ethnological Museum of Vienna gives us a first taste of Berlin’s Humboldt Forum to come

Following a three-year renovation period, the former Ethnological Museum in Hofburg/Vienna was recently reopened as the Vienna Weltmuseum (VWM). Responsible for content development and the presentation of the exhibits was the same museum exhibition design firm, Ralph Appelbaum Associates, which previously designed the Canadian National Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg and the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened by Barack Obama in Washington DC, and which is also currently preparing the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. Therefore, Vienna can be considered a test run for the major project in Berlin, which is also housed in a palace. At the Vienna Weltmuseum, we are able to paradigmatically study the state-of-the-art of ethnographic-scenographic exhibitions in the second decade of the 21st century, as well as the new role of contemporary art in historical museums, the latter of which I gave special attention to during my visit.

On the mezzanine floor, the artist Lisl Ponger presents her artwork in a separated black spatial installation right next to the new ethnographic showrooms. Exhibits on court hunting and armory are located on the floor above. © Johanna Di Blasi

On the mezzanine floor, the artist Lisl Ponger presents her artwork in a separated black spatial installation right next to the new ethnographic showrooms. Exhibits on court hunting and armory are located on the floor above. © Johanna Di Blasi

From my time studying in Vienna in the 1990s, I remember this as an ethnological museum that hardly fell short of the morbid mustiness of previous exhibitions in the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, where artifacts from Belgium’s colonies could be found placed next to animal specimens whose skins had become worn off over the years in storage or snakes which had lost their colour. I recall a long series of halls and showcases that were densely populated – literally crammed – with ethnographic exhibits revealing traces of dust and decay. I remember feeling alienated. I was also convinced I had seen a ‘hall of races’ in the Vienna Ethnological Museum which compared people. However, Google informed me that the so-called ‘Hall of Races’ was part of the anthropological collection in the nearby Natural History Museum between 1978 and 1996.

Back then, there was no mentioning yet of masterpiece dramaturgy in ethnographic museums. But today, visitors are pointed toward the top objects – the must-sees of the museum – with unmistakable signposting already in the entrance hall. One of the gems that no visitor should miss is the emerald green Aztec Quetzal feather headdress, which originates from around 1515 in Mexico and is listed in the inventory of the Wunderkammer (cabinet of curiosities) of Ambras Palace in Tyrol of 1596. Writings and pictures draw attention to other key exhibits on the orientation signs: a Chinese “throne screen”, the “model of a Daimyo residence”, “figures of court dwarfs” from the Benin kingdom, the “feather bust of a god”.

In the permanent exhibition area of the new Weltmuseum with its 14 halls, darkened showrooms in which the original objects are auratically presented also with the use of digital, interactive elements, alternate with bright “discursive spaces” on questions of representation in the museum (“Who speaks?”, “What is culture?”, “Whose view?”) and topics such as colonialism, art theft and – conveyed very illuminatingly – the racism and primitivism in Viennese ethnology. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Viennese ethnologists, such as Father Wilhelm Schmidt (1868-1954), were searching in missionary areas less for racial differences than for an Adam and Eve-couple to underpin conservative Catholic social doctrine; while social democrats and psychoanalysts polemicized against the Catholic-tinted field research.

One example of a “discursive space” in the new VWM: the hall “In the Shadow of Colonialism”.

One example of a “discursive space” in the new VWM: the hall “In the Shadow of Colonialism”.

© KHM-Museumsverband

No direct connections are drawn between the main exhibits of the approximately 200,000-piece Vienna collection and the problematic aspects of collecting “exotic” objects. The visitors are also not informed about for which objects restitution requests have been put forward. However, when it comes to “Montezuma’s feather crown” – as the jewel is called in the vernacular – the Viennese inevitably have the persistent demands for restitution in mind, which Native Americans have for many years been performatively expressing with drums, dance, incense and illustrations of “El Penacho” in front of the St. Stephen’s Cathedral[1]. At least, the task of curating the section on North America was assigned to a Native American.

On the Belle Etage, the Weltmuseum celebrates itself as an aristocratic Wunderkammer, (cabinet of curiosities) which owes its existence to the “Museomania” (Franz Ferdinand) of the Habsburg crown princes – and thus takes up an old narrative. On the other hand, in the special exhibition areas on the mezzanine floor, the VWM is tinkering with the image of a global migration museum. This reminds a little of the popular play “On the ground and first floor” by Johann Nestroy shown in Vienna theaters. It is a social farce, in which the junk dealer named Schlucker and his wife, Sepherl, who live in ruff conditions on the ground floor, are having trouble with money lenders, while on the first floor, servants of the millionaire Mr. Goldfuchs are preparing the evening ball.

In the new Weltmuseum, institutional critique is diverted to the discursive spaces and the contemporary art contributions in the special exhibition areas. Hence, the intervention of Viennese artist, Lisl Ponger, who claims to investigate “stereotypes, racisms and visual constructions at the intersection of art, art history and, above all, ethnology” was eagerly awaited. She installed a black, sarcophagus-like spatial wedge diagonally into the white marble gallery of the central hall of the pompous imperial museum building: an unmistakable architectural signal showing that she wants to shield herself from the surrounding environment and that she is not in line with the ideology of the institution.

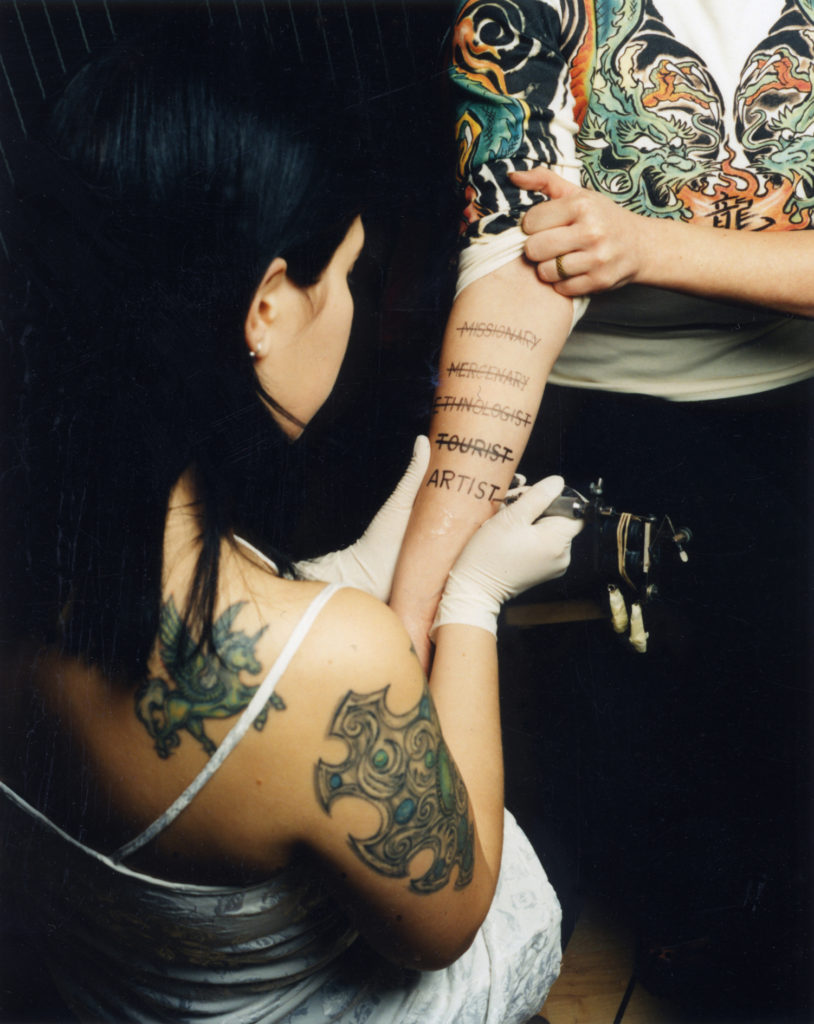

Within the separate space of the wedge, the artist or rather the MuKul, Ponger’s fictional Museum of Foreign and Familiar Cultures, presents staged photographs from various years (“Participating Observer”, “Otaheite Olé”, “Garden Party”) alongside a newly created 480-minute video piece (“The Master Narrative and Don Durito”, 2017). With the photographic artwork titled “Wild Places”, the artist places herself in the colonial tradition. It shows a female white hand being tattooed with the words “Missionary”, “Mercenary”, “Ethnologist”, “Tourist” and “Artist” by another hand; all words except “Artist” are crossed out.

Lisl Ponger’s photographic artwork “Wild Places” (2000). © Lisl Ponger/michael michlmayr

Lisl Ponger’s photographic artwork “Wild Places” (2000). © Lisl Ponger/michael michlmayr

A look into the special exhibition “The Master Narrative” (since October 25, 2017 in the VWM) by the artist Lisl Ponger: on the left you can see the photographic artwork “Garden Party”, in the middle “Teilnehmende Beobachterin” (Participant Observer), on the right one theme from “The Master Narrative”. © Lisl Ponger/michael michlmayr

A look into the special exhibition “The Master Narrative” (since October 25, 2017 in the VWM) by the artist Lisl Ponger: on the left you can see the photographic artwork “Garden Party”, in the middle “Teilnehmende Beobachterin” (Participant Observer), on the right one theme from “The Master Narrative”. © Lisl Ponger/michael michlmayr

At a meeting of experts at the Humboldt Lab in Berlin two years ago, which was functioning as the curatorial and scenographic experimental lab for of the Humboldt Forum from 2012 to 2015, Ponger provided insights into the necessary conditions for interventions in ethnographic museums. The most important thing are the working conditions. With respect to her involvement in the Weltmuseum, which was under restructuring at that time, the artist said:

“The autonomy of art is clearly stated in the contract. So, the museum has no way of intervening in my concept. For me, this means that I can express structural critique towards the colonial endeavor of the ethnographic museum, as no framework has been defined within which I am confined to, e.g. [in the form of] interventions in collections, etc.“

The artist is, nevertheless, aware that the museum can appropriate her critique and thereby present itself as a critical museum.

“It is a tightrope walk for me between critique and complicity with this colonial enterprise. The question is, how and whether one can distinguish oneself from this powerful discourse of the museum, because of course the colonial past is very often inscribed in the architecture, yet always in the collections of the museums, and Art cannot do much against that, but I have decided that it is better to fail terrifically than not to try it.”[2]

By ironizing and disclosing her own position both as an “embedded artist”, Lisl Ponger attempts to enlighten. However, the disclosure of one’s own dependencies can also be regarded as an immunization strategy against criticism by anticipating criticism. This ambivalence characterizes Ponger’s entire contribution. Through choosing her own separate space, the artist visibly secludes herself from the surroundings and demonstrates stubborn resistance, while remaining embedded within the Weltmuseum[3].

Through the “courtesy” declarations (Charim Gallery), the installation also has something of a private gallery showroom, realized within the public museum. It is also quite possible that the artist with her subtle humor has decide to dig her own grave in the Weltmuseum, freely adapting the avant-garde motto that museums are mausoleums; which should be understood quite literally considering the “human remains”, i.e. the remains of humans, in ethnographic museums.

As part of the opening exhibition, a special display has been dedicated to another artist besides Lisl Ponger. Rajkamal Kahlon, an Berlin-based American, was invited to a two-month residency[4] at the Vienna Weltmuseum and found what she was looking for in the museum’s ethnographic photo collection. The result is the exhibition “Staying with Trouble”, which consists of re-paintings of ethnographic portraits. The title is a reference to the biologist, philosopher of science and ecofeminist Donna Haraway (“Staying with the Trouble: Making Children in the Chthulucene”, 2016)[5].

The special exhibition “Staying with Trouble” by Rajkamal Kahlon. © KHM-Museumsverband

The special exhibition “Staying with Trouble” by Rajkamal Kahlon. © KHM-Museumsverband

With small, subversive, drawn interventions, Kahlon, who has Indian roots, was born in America and earned a Master of Arts degree in painting from the California College of Art, “releases” the typological, de-individualizing and dehumanizing depictions of indigenous people from the ethnographic grip and negotiates questions of her own hyphenated identity. The museum text importantly states:

“Through her visual analysis […], the artist examines these continuities and invites visitors to question their own gaze. […] a dissection of the visual legacies of empire. By redrawing and repainting the bodies of photographed native subjects, Kahlon allows for the rehabilitation of those bodies, histories, and cultures that have been erased, distorted, and maligned”[6].

Artists are responsible for subtle critique. Yet, the special exhibitions remain largely detached, next to the new showrooms and can easily be bypassed. The reopening of the former ethnographic museum as a Weltmuseum reveals the transformation from collection-based science museums of the 19th and 20th centuries to audience-oriented forums of world culture[7]. Typically, we find masterpiece dramaturgy, smart wording and homogeneous corporate design, which extends throughout the entire museum to the printed materials.

The hand-over from ethnological and anthropological scholars to scenography and PR artists has already taken place – and is probably irreversible. Scenography not only determines the design of the showcases, space and lighting, but also generates, controls and choreographs the content and the overall narratives of the Weltmuseum. The result seems smart and smooth, making one almost long for the old, edgy, cranky ethnographic museum. As an involuntary monument of imperialist and colonial persuasion, it was more honest in an old-fashioned way.

The former Ethnological Museum in Hofburg/Vienna. Archive images from around 1900.

The former Ethnological Museum in Hofburg/Vienna. Archive images from around 1900.

© KHM-Museumsverband

Archive images, dated between 1908 and 1912. © KHM-Museumsverband

Archive images, dated between 1908 and 1912. © KHM-Museumsverband

Johanna Di Blasi is a Berlin based writer, journalist and art critic. For several years she was editor of the features section of “Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung”, from 2011 to 2016 she was correspondent and editor of the Berlin branch of the publishing house Madsack Verlag. Since 2015 she has been working on a dissertation and book project on the subject of artist interventions in colonial collections through the example of the Humboldt Lab Dahlem. Since 2016 she has been attending the colloquium of the department Arts of Africa at the Freie Universität Berlin, Prof. Tobias Wendl.

translated by Ulrike Flader

____________________

[1] The connection to the Aztec ruler Montezuma or Moctezuma remains speculative. The exact origin of the 1.30m-high feather crown, which Mexico never officially reclaimed, as well as the circumstances of acquisition are unknown. The SPÖ and the Greens repeatedly demanded restitution. In the new VWM, the audience learns that the object, which is displayed in a case with electronic suspensions to protect it against vibrations, would “disintegrate” into dust at the slightest touch. Conservatory arguments also prevent any travel of the Nefertiti, the “top object” of the Berlin museums.

[2] Own transcription of audio recordings of the symposium “Historical Collection and Contemporary Art. A Discussion of Curatorial Strategies”, which took place on 2-3 July 2015 in the Dahlem Museums in Berlin. The recordings are deposited in the library of the Ethnological Museum Berlin. Translations by Ulrike Flader.

[3] At the Berlin conference, Ponger said that one needed to decide case-by-case whether her critique could be “acknowledged, or whether it would be appropriated by this institution with its powerful discourse. […] However, working outside the institutions is also not a viable option for me”.

[4] Rajkamal Kahlon’s residency was part of SWICH – Sharing a World of Inclusion, Creativity and Heritage and was co-funded by the European Union’s program Creative Europe. www.swich-project.eu.

[5] Donna Haraway also gave the theoretical impulse for the eco-feminist documenta13 by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in 2012.

[6] https://www.weltmuseumwien.at/en/exhibitions/stayingwithtrouble/#about-the-exhibition.

[7] Gail Anderson describes in “Reinventing the Museum. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift” (2004), a transformation from “collection-driven institutions to visitors-centered museums” and, as a result, a shift from disciplinary to multidisciplinary exhibitions; cited in Baur, Joachim (ed.) 2010. Museumsanalyse. Methoden und Konturen eines neuen Forschungsfeldes, Bielefeld: Transcript, p. 220.