“… there is an unimaginable struggle going on.”

Berlin, Germany, 11 March - 29 May 2020

This diary was written by Claudia Liebelt from Wednesday, 11 March 2020, to Friday, 20 May 2020. Claudia is a Political Anthropologist interested in debates on gender and sexualities, the biopolitics of beauty and embodiment, postsecularism and new materialities, with a regional focus on the Middle East and Turkey. From October 2019–March 2020 she held a Guest Professorship of Gender and Diversity Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin. On April 1, she started working in a Heisenberg Position at the University of Bayreuth. During the lockdown, she lived with her partner and her 7-year old daughter in a 3-room apartment in Berlin-Neukölln. In mid-March, when the Corona lockdown began, she was preparing for a longer stint of field research in Turkey scheduled to begin in early April. This diary has been anonymized, that is, confidential data has been left out and contacts were given pseudonyms to make them less identifiable.

Wednesday, 11 March 2020

Midmorning, I receive an email from the Chancellor of the University of Bayreuth that all teaching operations are discontinued ‘until further notice’. For lunch, I meet with a new colleague at the University of Bayreuth, who lives around the corner from me in Berlin-Neukölln. His family lives in Northern Italy in one of the first so-called ‘red zones’ that were especially hard-hit by the coronavirus. This is the first time that I feel really unsure about the appropriate form of greeting. We decide on a brief hug, albeit with a certain distance, which is certainly less intimate than a peck on the cheek as is common among Italian friends. My colleague was planning to visit his family in Italy over Easter which now is out of the question. His brother suffers from keeping his children occupied at home all day long and they have daily video conferences now.

We meet at Caffeggiando’s, our regular Italian neighbourhood café. Its owner Massimo is from Turin and his family is likewise affected by the lockdown. He worries about his mom and also about the fact that he might have to close his café in the upcoming days.[1]

Thursday, 12 March 2020

I must have caught a cold from working in my unheated office on Tuesday: I wake up with a headache. My partner Ulaş takes our daughter Meira to school, I work from home.

In the afternoon I meet a colleague in a Kreuzberg gallery to see a photo exhibition about Merve, a legendary Berlin publisher. We no longer shake hands but wave at each other from a distance by way of a greeting. Over a beer in a pub next door we joke about the US president Trump’s treatment of the crisis and his recent entry barrier for Europeans. My colleague, an American, tells me that his American friends are worried about him because he is now stuck in Europe. “They don’t realise I actually live here,” he says.

Back at home, I take a paracetamol and go to sleep. It is 5 pm in the afternoon. Is this COVID-19 already?

Friday 13 March 2020

Sleeping for more than twelve hours did the miracle: I feel fine again. Meira leaves for school while in the chatroom of her classmates’ parents news about an imminent closure of schools make the round. Several parents already keep their children at home today, out of fear of infection. They complain that the government reacts too slowly. Another mother writes that she’s busy cleaning because ‘the virus attaches itself to all kinds of surfaces’.

Shortly before noon, the official announcement about the school closures reaches me. From Tuesday until after the Easter holidays (April 20), all schools and kindergartens in Berlin will be closed. Five weeks without childcare! This is a decisive turning-point with tremendous effects on my and most of my social circle’s everyday life. Within a few minutes our neighbours’-chatroom is busy with ideas on how to share childcare and establish a ‘backyard-school’ during the upcoming weeks.

Another email from the Chancellor of the University of Bayreuth states that each employee with children beneath the age of 12 will be granted ten days of extra holidays to cope with the temporary close down of schools. This is certainly welcome but I wonder how single parents will be able to cope with the remaining fifteen days. Everybody is advised to work at home or in tele office whenever possible. I wonder what happens to my new work contract at the University of Bayreuth which is due to begin on April 1st. About two months ago, I sent off everything I was supposed to submit but haven’t heard back from them since.

In the early afternoon, a skype conference with my colleagues from the German Anthropological Association’s working group “Gender & Sexualities | Queer Anthropology“. We have been organizing a two-day workshop to take place next week and a few days ago decided to postpone it to early October. Now we discuss how to move on. We will try to start a virtual discussion with the workshop participants. We would also like to write a joint essay on “Queering COVID-19” about the current situation from a queer perspective, something we have been missing in the beginning debate (most of us read the Somatosphere’s COVID-19 forum).

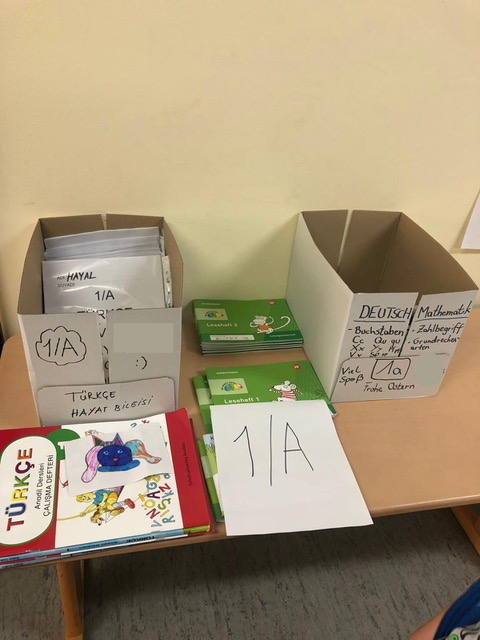

In the afternoon, Meira returns from school with an incredibly heavy school bag: She brought home everything she had in school: her sports bag, all her books and exercise books, her utensils for the art class.

Today is my friend Caro’s birthday. Caro is an independent historian and publisher, who in the past few years has worked for several NS memorial sites. After some deliberations whether it is still okay to meet with a group of friends in a pub, she invited a rather small group into the backroom of a quiet pub for dinner. Out of the eight persons invited, six arrive. We sit at a distance from each other though certainly less than a metre and a half. The atmosphere is rather gloomy as the news pour in that from tomorrow onwards, all pubs will be closed in Berlin. Caro and some of the others are great fans of Christian Drosten, the director of the Berlin Charité’s Institute of Virology. Caro has started listening to his regular radio podcast and is prepared for the shutdown to last several months. She and some of the others work as historians in different NS memorial sites and accordingly, they wonder what the shutdown means for their institutions and professional futures more generally. We also talk about the situation of refugees at the Greek-Turkish border. The media images from Lesbos are disturbing. From participating in a no-border camp in Lesbos in 2009, I know some of the camps that are currently on the news. Even back then the situation was unbearable for those arriving from Turkey.

Saturday 14 March 2020

The weather is mild and sunny and during the afternoon there is a spontaneous meeting with the neighbours in the backyard. Most of us are unsure how to deal with the current situation. Some say they will reduce their social contacts to the people they live with as soon as the schools close down, others are not able to do so as long as they have to work. One Italian neighbour Emilia whose family in northern Italy is under quarantine already suggests to organise a mutual support system for all neighbours. Another neighbour, Jasmin, sets up a shared online table to facilitate the collective organization of childcare in the backyard during the upcoming week.

Sunday, 15 March 2020

The first real spring day of the year, everyone is out and the corona crisis and imminent lockdown seem far removed from the social reality around us. I go for a walk with Caro who was recently offered a position and, like me, wonders whether the hiring process will be processed as scheduled in spite of the current situation.

My partner Ulaş returns from running on the Tempelhof Airfield. He jokingly remarks that half of Berlin’s population is hanging out there. The playgrounds are packed with families too.

At night, we watch the news for the first time ever with Meira. She is unimpressed by the discussion about travel restrictions but is sad when we tell her that due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, we will not be able to move to Istanbul anytime soon.

Monday, 16 March 2020

The final day of school until at least April 20 for Meira. Out of the 21 children in Meira’s class only six attend school today. She returns with a pile of copies, her homework. She is in a good mood because they had a very early Easter party with chocolates. She is happy that she was chosen to take home and care of Mo, the teacher’s glove puppet, while the school is closed.

Yesterday was the deadline for submission of my students’ essays and even though I extended the deadline in many individual cases, my email inbox is packed with essays. I save them into a folder on my desktop and start reading the first. Even if I manage to read 3–4 a day, the maximum per day without childcare, I suppose, I will not finish reading them before the end of the month when my contract with the Free University ends.

Tuesday, 17 March 2020

We meet our 90-year old neighbour, Mrs. J., with her caregiver in the hallway. We exchange telephone numbers and offer our help with shopping or other services, just in case her caregiver could no longer come. The caregiver goes to see Mrs J. once a week from an outer district to clean her flat, do the shopping, and to go for a walk with her. The caregiver is worried that she might fall ill or else is no longer able to come. Mrs. J. does not leave the house alone. She has a daughter who lives in another part of Germany and rarely comes to visit her.

Today is the first day of school and kindergarten closures in Berlin. After breakfast, we set up a weekly school schedule with Meira. We include English lessons even though she hasn’t had any so far. We do so because Meira’s prospective class in Istanbul started with English lessons last August. We don’t want to give up on our Istanbul plans yet. We already bought the books the Istanbul school works with. In case we still manage to leave for Istanbul, I want Meira to be at least a little bit prepared. In the past few weeks we’ve repeatedly looked at the pictures of her prospective school and class on the internet. We’ve noted that one of the girls resembles one of her Berlin friends. We looked at the photo of the teacher, a youthful blonde, and wondered whether she was strict. We schedule two hours of home schooling in the morning, time in the backyard until around noon, and another hour of home schooling after lunch.

While I visualise our schedule Meira paints a picture of a huge corona virus hoovering over a scene with two people sitting beneath a tree. They have large fearful eyes and one of them exclaims ‘Aargh!’

In the afternoon, one of our neighbours receives a telephone call from the parents of their son’s best friend: his father just fell ill after visiting his sister in Munich the previous weekend. The sister has now been tested positive for COVID-19, he is still waiting for his test result to arrive. The news is discussed among the neighbours in the backyard. What if our neighbours’ son, Olle, has been infected? Two other kids who regularly play in the backyard are in the same after-school care centre, together with the potentially infected boy. Olle’s parents are rather calm, but Timm, one of the other boys regularly playing with Olle in the backyard, suffers from chronic asthma, so Timm’s parents do not wish to take unnecessary risks. Timm’s mother decides to temporarily isolate her son from the backyard group, at least until the other father’s test results have arrived.[2] From other acquaintances we know that the arrival of test results can easily take up to a week in Berlin these days. We notice how the virus becomes less abstract and slowly moves into our social circles.

A long conversation with my mother over the phone. She returned to Berlin in late January from her house in the Marches, in Central Italy. The Marches are now heavily affected by the Coronavirus outbreak and my mother tells me that her gardener thinks he already had the virus in February. Other people we know have been diagnosed and a distant acquaintance’s son, who was in his twenties, has died. My mother went into self-quarantine in mid-February because of her Asthma. Her husband continues to work in a film studio in Cologne and stays in Berlin over the weekend. We used to see each other at least once a week for a joint lunch at the Centro Italia, an Italian supermarket and restaurant close to where they live. It’s almost a month now that we haven’t been able to get together. My mother continues her translation work and she also keeps herself busy by tending to her garden, she says.

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

I continuously receive emails from students explaining why they were unable to submit their essays in time. A French student describes how she was able to catch one of the last flights to Paris, but then waited for two days until she was finally able to catch a train to her family’s place in Southern France. Due to the restrictive lockdown in France she worries that she will not be able to post a printed version of the essay. I set up an email to all students explaining that they no longer need to worry about mailing their essays in addition to the digital copy.

In the past few days, I received Coronavirus regulation updates from the Chancellor of the University of Bayreuth on an almost daily basis. Today, I receive three official messages from the university. In the first message we are told that all cafeterias and libraries will stay closed until further notice. In the second all employees with experiences in the health sector are requested to come forward. In the final one the Chancellor speaks of great challenges ahead of us, the “academic family”.

During the afternoon, I make pottery with some of the kids in the backyard. After about two hours I have a large collection of little pots, hedgehogs, hearts, and fantastic animals, which I take to the workshop of my friend Einat, a ceramicist. Upon leaving the workshop another friend enters. She looks worried and hardly says hello. At night, I receive a message from her. She apologises and explains that she was extremely stressed out. Her flatmate was stuck in Munich for days after an odyssee from Spain.

Some of our neighbours have created a WhatsApp-group called “Playing in the Backyard,” which includes all neighbours whose children regularly use the backyard. This is the beginning of a debate on how to use the backyard during the lockdown. Some families went into self-quarantine already. Others wonder whether we should form smaller groups or self-restrict our kids’ access to the backyard. It is difficult to imagine what we would do if Meira, who is incredibly energetic, lost her access to the backyard. We watch the evening news and chancellor Merkel’s speech with Meira. Meira repeats her main sentence “The situation is serious, please do take it serious”, imitating her earnest facial expression and then bursting into laughter. Watching the news with Meira means that you have to watch them again after she’s asleep if you wish to listen to more than a few fragments.

Thursday 19 March 2020

Today would have been Day 1 of an inaugural workshop titled “Queer Openings” that I co-organized with five colleagues at the FU Berlin. I had been looking forward to this for so long! Like so many other workshops and public events, ours has not been cancelled but postponed to early October.[3]

Concluding our two-day workshop in a public round table event at the Schwules Museum Berlin (Berlin Gay Museum), we were hoping to discuss the state and future of Queer Studies within the wider German-speaking academy. Our four speakers would have discussed the reception and politics of Queer Studies amidst a political climate in which right-wing populists discredit the work many of us do. Instead of holding the public event, we created a closed group for discussion on a social media platform for the workshop’s participants. The discussion hasn’t really started yet; while it seemed like such a timely and relevant debate just a few days ago, today it seems rather remote from what is happening all around us. Everybody seems to be busy organizing their everyday lives in this early phase of the coronavirus outbreak in Germany. In my case, this means home-schooling and entertaining a rather energetic seven-year-old who does not comprehend why all of a sudden we can no longer visit her grandmother or go to the public playground at the corner.

For almost a week now I receive daily updates from the presidents of the two universities I am currently employed by, the Freie Universität Berlin, the FU, and the University of Bayreuth. Today, there are multiple announcements from both sides. After the second email from the president of the FU, I realize that as of tomorrow, the university will shut down almost completely and that if I don’t clear up my office today, I might not be able to do so anymore since my transponder will be blocked and my contract with the FU terminates by the end of the month. I leave Meira with the neighbours in the backyard and take the car to empty my office on the other side of town, in Dahlem. Listening to Deutschlandfunk, the major public-broadcasting radio station in Germany, on the way, I have the feeling that a .public curfew is only days if not only hours away. Commentators report about careless young people in ‘certain parts of Berlin’ socialising freely in parks and cafés, obviously not sticking to the chancellor’s request to stay at home as announced on German public service television the night before. They most likely speak about our neighbourhood (among others): the Landwehrkanal is packed with people enjoying the first days of spring.

In Dahlem, the streets are rather empty, as usual. I work hard to quickly fill the cardboard boxes that I stored away in the little storage room at one side of my office after moving in six months earlier. I will miss this place and my colleagues, but now is not the right time to sentimentalize. Having packed everything, I move on to the department’s secretariat to return my laptop and transponder. On the doors of the institute’s villa, large signs tell students to STOP due to the coronavirus. The secretary and the study coordinator are also busy packing and getting things done before moving into home office the day after. We don’t shake hands anymore and U put the flowers that I brought to say good bye on the desk between us. It is difficult to say goodbye to someone you grew attached to without any physical contact.

Friday, 20 March 2019

After a first round of home schooling, my daughter Meira disappears into the backyard, singing her new earworm, which she brought home from school (a bilingual Turkish-German school), in Turkish: “Corona, Corona, everywhere Corona; I put on a mask: Corona; Corona! Corona, everywhere Corona.”

Instead of meeting my PhD student in my office yesterday, we now have a video call with her sitting in her apartment in Zurich. We discuss our upcoming research project, which will hopefully take her to conduct ethnographic fieldwork in China. However, it is rather unlikely that China will grant entry to Europeans in the near future. Also, when will the University of Bayreuth approve of business travels to China again? Like my own field research to Turkey which was scheduled to begin in early April, her research plans are currently on hold. She is clearly worried. In contrast to Berlin, where the ‘transitioning to minimal on-site operation’ as it is officially known, took place during the semester break, in Zurich, where she teaches, the semester is in full swing. Since Friday she is required to teach online and having little experience in teaching, struggles to manage the sudden transition.

Listening to the radio while preparing lunch, I realize that the curfews are getting closer, with Bavaria and the Saarland being the first federal states to introduce at least partial curfews. Then a WhatsApp message arrives in the parents’ chat group of Meira’s class, showing the website of the Berlin Federal Bureau for Public Health and Welfare, the LaGeSo, announcing a Berlin-wide curfew from Monday morning. Within a minute another parent exposes the posting as a fake; indeed, when I check the LaGeSo’s official website, it already features a warning.

In the early afternoon I venture outside for the first time today to post some letters. I do so in a nearby kiosk rather than the post office which is usually crowded during this time of the day. On my way back, I chat with a neighbour who leans out of the window smoking a cigarette and listening to music in an otherwise quiet street. When I tell her about the fake LaGeSo website she tells me another incredible story: apparently, a group of men in protective clothing currently goes from door to door claiming to be health officials and requesting that people take (fake) corona tests for which they then charge a fee. She has heard the story from a friend.

For dinner, I prepare a challah and light candles like I usually do on Friday nights, the beginning of the Jewish shabbat. It feels good to stick to this weekly ritual even during these turbulent times. Our dinner for three makes us remember those we miss and usually have dinner with on Friday nights. Meira misses her grandma who is home alone in another part of Berlin, in self-quarantine since mid-February due to her chronic asthma. For the second consecutive day at 9 pm several neighbours applaud from their windows in solidarity with the medical staff treating those suffering from Covid-19.

Saturday 21 March 2020

The first week of home schooling is over and Meira is obviously getting bored with staying at home or in the backyard all the time. We discuss cycling to the Tempelhof Airfield and try to explain why we would not be able to stop at her favourite toy shop and café on the way. Taking out our bikes we notice that other neighbours decided likewise to take their kids to a bike trip. In contrast to last weekend when thousands of residents flocked to the former airfield, causing much moral outrage in the wider German public about the careless Berliners not acting responsibly in the current crisis, this morning it is rather empty. Perhaps due to the cloudy sky and fresh breeze. The few groups we encounter, mostly couples and families with smaller children, move in distance from each other, mostly on bikes or inline skates. Even after the sun comes out in the afternoon, the public playground around the corner remains almost empty. In normal times on a sunny Sunday afternoon it would be crowded with dozens, possibly more than a hundred people.

Instead, we stick to the backyard of our gated housing complex which has its own playground. The housing complex we live in was built in the 1920s by the visionary Bruno Taut, an avantgarde urban planner/architect and an early follower of the Garden City movement. Hence, the complex is built around a large backyard, complete with a lawn, a playground, a little hut for garden tools, vegetable and flower beds that we care for collectively, as well as numerous large trees and bushes, perfect for hiding and climbing. Early on in the process of the COVID-19 crisis and the public appeals to stay at home the regular users of our backyard, nine families with their small children, started discussing on how to deal with the situation as a community and how to keep on using it. Most of us decided that we would not try to keep our kids inside the house all the time but would like to continue using the backyard together. Two families have since withdrawn from the backyard, one because they sought to minimise their physical contacts even further and another, because they felt they were too exposed in their professional lives to intermingle with the rest of us.[4] The remaining families agreed on reducing their own as well as their children’s social contacts to an absolute minimum outside of the housing community, at least since all schools and kindergartens closed down on March 17th. We decided to meet in the backyard exclusively, keeping physical distance from each other and try to explain to our kids to do so as well.

Nevertheless, the degrees of self-quarantine among us vary and the debate about intermingling in the backyard continues. Some have proposed to use the backyard in shifts of regular groups of kids to minimise the risk of infection. For the time being, however, the housing community is a great relief in everybody’s quarantine-like everyday lives. Thus, we take turns in entertaining and supervising the children for two hours in the morning and two to three hours in the afternoon. Most of us work at home these days. We’ve supported each other with shopping, taken comfort in each other’s concerns and anxieties and exchanging news and jokes via social media. Also, on March 16 and 17, we’ve provided the elderly in our respective housing units with our phone numbers, offering them to be available for general support or shopping. Before we return inside this afternoon one neighbour fetches a bottle of exquisite whisky to cheer us up in light of the gloomy news of 800 new corona deaths in Italy. Standing at a distance from each other we toast to the eventual passing of the pandemic. At 7 o’clock that evening a much larger number of neighbours as compared to yesterday pays respect to the medical personnel by applauding from their open windows.

For the first time I see queues in front of the local supermarket due to the fact that it started to limit the number of persons allowed inside.

Sunday, 22 March 2020

Over breakfast my partner Ulaş reads out the news from Turkey where those aged 65 and above are no longer permitted to board a plane. This also affects his parents, who live on the Aegean coast in the province of Bodrum; they write that they were told to stay at home and nowadays leave the house for shopping only. Bodrum is a popular holiday resort for Istanbul’s upper middle class. In the past few days they claim the town has been ‘flooded’ with Istanbullus seeking refuge from the potentially infected city. In Turkey the spread of the epidemic has long been denied and officially confirmed numbers are still a few hundred only while many seem to go unnoticed. Ulaş spends much time on getting information about the situation in Turkey. There are reports about the rise of conspiracy theories, often with an anti-semitic undertone.

I get samples of such theories from the WhatsApp chat group of the parent support association of our daughter’s school, a bilingual Turkish-German school, with an overwhelming majority of parents from a Turkish cultural background: yesterday evening one mother posted a link to a website called Eurasia Diary and begins her message (in Turkish) with a question: “Could this be a coincident?” She then goes on to explain that two US American publications from the 1980s, The End of Days and The Eyes of Darkness, have predicted the pandemic and that a ‘certain group’ which holds secret power within the US state and is linked to the Rockefeller family network is interested in an economic global breakdown to introduce its own digital currency. The posting is incredibly long, quotes a number of Turkish “experts” with academic titles and ends with the assumption that the current situation has been planned by ‘secret forces’ from within the US to harm the global economy and especially Turkey. I am reminded of the conspiracy theories that I encountered during field research in Turkey in 2013–2014 which I found deeply disturbing for their rampant and rather open antisemitism.

I try to concentrate on reading student papers and answering emails. Every day now I receive emails from students explaining why they were unable to submit their papers in time, asking for an extension of the deadline. Today, a student explains that she is in quarantine waiting for the result of her COVID-19 test because she used to work at the reception of a hostel that accommodated someone tested positive. She obviously is too depressed to work on her essay.

Meeting some of the neighbours in the backyard during the afternoon while news from a meeting of Chancellor Merkel and the heads of the Federal Governments pour in, we discuss the use of the backyard in the upcoming week once more. While the regulations relate to public space exclusively we nevertheless decide to split into two groups, one comprising six children from four households in the morning and the other comprising the same number of kids from three households in the afternoon. We also draft a letter to the other neighbours explaining our decision as one that hopefully comes across as responsible. When we explain to Meira that from tomorrow on we could not use the backyard during the afternoons she tells us ‘I don’t care. I will go to there whenever I want to’.

Monday 23 March 2020

This has been a rather frustrating and tiring day, the first day of the federal government’s tighter regulations regarding the COVID-19 outbreak. After a first round of home-schooling in the morning I have a long conference call with our neighbours from our “playing in the backyard” group about how to go on. It is clear to all of us that while public playgrounds are closed and groups of more than two (unrelated) individuals are not allowed to gather in public we cannot go on using the backyard the way we did until yesterday. For some, using the playground with six kids simultaneously, as planned only yesterday, also seems out of the question today. The atmosphere of discussion is tense and each of us feels threatened by the prospect of losing access to the garden. Some are anxious that the other neighbours could report us to the property management or even the police if we continue to share using the space with kids who do not keep physical distance from each other. After some lengthy debates and a collective reading of yesterday’s regulations we divide our kids into four groups, each using the garden for up to 1.5 hours a day. Each group will comprise one adult with their own and another household’s children. For us, like for everyone else, this will create an entirely different childcare situation. It means that we have less time to work during the day, we will need to work longer at night and get less sleep. One neighbour, who lives with her husband and three kids in a two-room flat, says that without the backyard and the regulations in place she is afraid they might eventually kill each other. This is meant as a joke, but the desperate undertone in her voice cannot be overheard.

In the afternoon, we go for another cycling tour with Meira. It is a freezing but sunny Monday; it feels more like a Sunday though. There is little traffic and bicycles seem to have taken over the street. Many shops are closed and there are long queues in front of the supermarkets.

At night, I talk to a friend from Jerusalem. The regulations they are subject to are rather similar to ours; however, they are much more tightly controlled and are not supposed to move away too far from their registered address. Schools there closed right after the Jewish carnival, Purim, about two weeks ago. Her husband who works in tourism has taken his annual leave and will have to register as unemployed if the travel ban continues until May.

Tuesday 24 March 2020

My daughter Meira’s timeslot for using the garden is from 10.30 am until noon. After a first round of home schooling, Meira packs her backpack, waits until the kids of the first garden shift return inside and storms outside to reunite with her friend Raya. The playground has been cordoned off and two parents from neighbouring housing units are already drafting a letter to the property management asking them to remove the barrier tape, explaining our scheme. In the afternoon we see that the children have already made creative use of the barrier tape. On my way downstairs to unlock the door leading to the backyard for Meira, I check the mailbox: again, no letter from the University’s Human Resource Department. I am waiting for forms that I need to fill in so that my work contract can be finalized. The secretary responsible for this claims that she sent them out on Thursday and that the postal office is currently overburdened. My work contract is due to begin in six days, on April 1st. Obviously, the Human Resource Department started to process my documents which were submitted in mid-January, way too late. Most administrative secretaries have moved into home office by now and the university mail is fetched irregularly. I find it difficult to understand why these forms cannot be sent out in digital form via email. What worries me most is that in case my work contract does not begin on the first of April and depending on my future salary, I might not be covered by medical insurance after March 31st.

I spend almost an hour on the phone with various secretaries from the insurance company and the university before Meira wisely persuades me to paint something with her. We fabricate a birthday card for my brother who lives in Vienna and leave the house to post it. Meanwhile, the kiosk where we used to post our mail has closed. When we see the incredibly long queue in front of the post office we return home without having achieved much. On the way back we have a long chat with the regular beggar in front of our supermarket. He has had a cough for quite a long time and notices that in the past few days people started avoiding him even more than usually. Due to his ill health he is scared to be infected and knows that by standing in front of the supermarket he is rather exposed to the virus. However, he depends on the money and has no choice. He asks me to buy a box of tea bags for him, flavour lemon-ginger.

In the afternoon, a long phone call with a friend, Mona, to whom we sublet our former rented flat around the corner (when we moved out of the flat two years ago, this was the easiest way to make sure our friend would get the flat). After several letters and phone calls in January, the house owner finally agreed to officially rent out the flat to Mona but requested an inspection prior to changing the contract. We agreed on a date in early April but due to the fact that Mona, who has just returned from India, is currently under quarantine, this now has to be postponed. She tells me about her stressful and exhausting journey back from Mumbai: several planes were cancelled and when the German embassy finally decided to evacuate its remaining citizens, she was waitlisted for another three days. In the airport Mona met one of my colleagues from the University of Bayreuth who was likewise on his way back from fieldwork. They are both desperate about the missed opportunity to do fieldwork and unsure whether they will be able to afford postponing it. Mona is deeply worried about the spread of the virus in India; at night a TV report about the spread of the coronavirus in India confirms much of what she told me, namely that the urban poor are especially at risk because they have to deal not only with the medical but also with the severe economic effects of the strict COVID-19 lockdown.

At night, a conference call with my colleagues doesn’t work out. Another conference call with friends in Israel does work out but it leaves me rather depressed. According to plan they would have been busy packing their bags to come and stay with us in Berlin while we would have left for Istanbul the week after.

Before going to sleep I read and sign a petition initiated by a group of professors two days ago demanding a ‘non-semester.’ This means the semester should not ‘count’ in order to create space for those students (and teaching staff) who have childcare or other care obligations as well as problems with their visa or residence permit due to the COVID-19 epidemic.

Wednesday 25 March 2020

In the morning after home schooling and while Meira is in the backyard with Raya, the only friend and neighbour she still sees, I continue to correct student essays. I manage to read 2–3 a day but instead of getting smaller, the pile of essays that sits on my desk keeps on growing. I hope not to run out of ink for the printer. If I do, I might have to violate my self-imposed Amazon boycott.

In the afternoon Meira, accompanied by Ulaş, has an appointment with a dentofacial orthopaedist and returns with her first braces. She is excited and hyper, constantly taking it out and putting it back. It is my brother’s birthday today and we have a zoom conference with him, my mother and her husband as well as my sister and family. With a curfew in place in Austria since March 16th, my brother was forced to move into home office a while ago. His employer, an architectural firm in Vienna, had his computer and documents delivered to his apartment the day the curfew was announced. He jokes that he probably works more now that he stays at home than he did when he was in the office. He misses playing table soccer with his colleagues during breaks in the afternoon. My sister and her father, both actors, laughingly tell us about the scenes they did before the shooting stopped. How does one act a heated argument when one’s film partner is filmed separately? Apparently, some soap opera’s screenplays are currently rewritten to allow to take up the shooting as soon as possible.

Eventually, my work contract and a large file of documents have arrived! It takes about two hours to sign and fill in everything. In order to avoid the post office, I follow a friend’s advice and buy stamps online for the first time. I take the envelope to the post box straight away. On my way there I notice that the streets are much more crowded than they used to be two days ago when the restrictions were still new.

I chat with a Turkish friend in the UK. She tells me that she thinks the German government, in contrast to the British one, is doing a fantastic job. I tell her that we’ve all become followers of Drosten Süperstar and send her a link to an article about him in The Guardian. Among my friends, many indeed have become great fans of Christian Drosten, the director of the Berlin Charité’s Institute of Virology, and I too regularly listen to his radio podcast.

Thursday 26 March 2020

In normal times I would have left to clear out my father’s house in Southern Germany tomorrow or on Saturday. My father died last summer and I didn’t have the time or capacity yet to clear out the house. About a month ago I made an appointment for early next week with a team of house clearance specialists from the Workers’ Welfare Association. I talk to them on the phone and the responsible person tries to persuade me to stick to the appointment, probably because in the current situation they need the income. However, during the day I grow increasingly nervous about the prospect of driving 700 kilometres through Germany. I hear reports about Berliners being sent back to Berlin by police officers from other federal states. I check the regulations of the states on the way to my father’s house and realise that in contrast to Berlin, they all have rather strict curfews. In Saxony-Anhalt and Bavaria it is okay to organise a change of flat (which is somewhat comparable to receiving a team of house clearance specialists) but it is not allowed to travel to one’s second home (this rule was probably introduced to keep people from the urban centres to move into their holiday homes on the northern islands and in southern Germany in large numbers). I try to find out whom to contact about an autobahn transit through Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Bavaria. The only official number that I find is from the Government of Saxony-Anhalt; it is busy all the time. I write emails to the different states’ Ministries of the Interior briefly describing my case but do not seriously expect an answer before tomorrow. I should probably cancel the appointment right away. I try not to think about my father’s well-groomed garden which has probably turned into a jungle by now (in the middle of a residential neighbourhood with very well-groomed gardens).

Today, I manage to read only two student essays and I feel that more and more things to do are piling up on my desk. I take Meira for a long walk to Krumme Lanke instead, a beautiful forest lake in western Berlin. Another gleam of light is the publication of a blog post that came out of one of my seminars. It is published on the wonderful Encounter blog and deals with places of beauty consumption and bodily wellness as spaces of social encounters in the city. In the current situation, this sounds like a story from another age!

Friday 27 March 2020

I cancel the trip to my father’s house. At the moment, a trip to the other end of Germany seems just too risky. Instead, I call my cousin, who lives close to the house. Her husband was tested positive for COVID-19 yesterday and is in bed with high fever. She takes care of their three kids and sounds rather desperate. At the same time her mother, my aunt, is in the local hospital’s intensive care unit after a cardiac valve operation. Her condition was critical for over a week and while she is now slowly recovering, her heart insufficiency is ongoing. For almost two weeks the hospital no longer allows for visitors. My cousin tries to reach a carer or nurse every day to find out about her mother’s condition. After this phone call it is difficult to return to work. I manage to read just one student essay during Meira’s time in the backyard today.

In the afternoon, a walk with a friend, Anna, who hasn’t been outside for the past ten days. We take a stroll through Treptower Park, next to river Spree and she is surprised by the fact that many people are out. Anna works as a bookseller in a renown independent book store in a posh neighbourhood in Berlin’s West. She is currently on holidays. She was planning to visit our mutual friend Inesh in the UK, but had to cancel her trip. I tell her that the friend she was planning to visit, a medical doctor, has now been called up to serve in a London clinic. She hasn’t even called him to tell him that she cancelled her trip because this seemed so obvious. Anna is a bit anxious about returning to work in the following week, especially about using the subway. She muses about cycling, which would take her about 50 minutes one way.

Today, I prepare two challahs and give one to our friends, an Israeli-American couple, who live a few hundred metres down the road. The challah handover takes place by the canal. As we sit on a bench and chat, we watch a team of policemen going up to people sitting on another bench telling them to move on. We quickly do. At night, my friend Caro complains on facebook that, lazing around in a park during the afternoon, she was approached by a team of policemen telling her that she was supposed to come to the park for sports only. I wonder whether it would have helped to tell them she was meditating. How do you define sports anyway? We joke that after all, playing chess is recognized as sports by the International Olympic Committee. Indeed, in contrast to many other federal states in Germany, in Berlin one has to have a convincing reason for leaving the house. Listening to music or reading a book in a park is obviously not enough of a reason. On my way home, I see other teams of patrolling police.

After dinner, we watch my father’s old slides. There are several thousand of them and I want to select some for digitalization. Watching slides from my parents’ journeys to Austria, southern Tyrol, and Italy in the late 1960s, we miss travelling. We tell Meira that once the epidemic is over we will take her to Rome. We think of my mother’s house in the Marches that stands empty these days and wonder whether we will be able to go there during the summer as we usually do.

Watching slides of past journeys, here to Venice in the late 1960s (Photo: C. Liebelt).

At about 8 pm, like the night before at about 2 am, an ambulance stops in front of our house, no sirens but emergency lights on. A team of paramedics enters our house. I keep Meira from running out. She wonders if someone died, remembering the ambulance and paramedics that entered our house when her grandfather died while staying with us eight months ago. We try to comfort her but I wonder whether this is related to the outbreak of COVID-19. I breathe a sigh of relief when they move past our floor, worrying about Mrs. J., our 90-year old neighbour living next door. Perhaps the Turkish gentleman on the third floor, who has had heart surgery three months ago?

Saturday 28 March 2020

In the afternoon our friend Jasmin, who lives on the fourth floor, returns from hospital. I talk to her from the balcony: tidying up something in her kitchen, she fell from a chair and slashed open her underarm. Luckily a friend was around to call an ambulance. Her arm is in a plaster cast now. I am somewhat relieved that no COVID-19 patients were taken from our house (yet..).

During Meira’s hour in the backyard I read students’ essays, edit the second part of a blog post written by my students, and answer emails related to my position of review editor for an anthropological journal, the Sociologus. I’ve become rather efficient in time management, but still, things keep on piling up. I was hoping to write an article with colleagues from the German Anthropological Association’s Gender & Sexuality | Queer Anthropology working group that I am part of but can’t find the time to do so. In the afternoon I manage to read a friend’s latest publication which has been lying on my desk for quite a while and take a walk with Meira. Watching slides at night, again from Southern Tyrol and Italy. The images of carefree holidays serve as a stark contrast to the mediated images of COVID-19 related deaths and hospital scenes. Especially disturbing today are the images of convoys of military vehicles transporting bodies in northern Italy.

While Ulaş goes to sleep early these days, exhausted from hanging out at home and spending time with Meira who is full of energy as usual, I stay up longer from day to day. After everyone went to sleep I watch an excellent and inspiring documentary about Donna Haraway, Story Telling for Earthly Survival. She argues that what matters perhaps most in these existential times –referring to the climate emergency– is what kind of stories we tell each other. This rings true in the current pandemic and it is moving in its empathy and simplicity; are our visions utopian or dystopian, are we telling each other stories of empathy and solidarity, or of an egomaniac survival of the fittest? I can’t wait to discuss the film with my new “FemaleFutures”-group, that some of my neighbours set up (we have a zoom date for this on Wednesday).

Sunday 29 March 2020

The clock has been switched to summertime and we get up late. Breakfast while reading the newspapers that have piled up during the week. While Meira is playing with her friend in the backyard I return to my laptop. Time to work has become just too precious to not work on a Sunday. The first email this morning is from the German Rail Service: they agree to refund my tickets for a journey to Passau where I was supposed to lecture a few days ago. It took them a while to respond to my request: I cancelled the trip on March 12!

With the raucous noise of helicopters in the air and the clouded weather, the atmosphere is rather gloomy today. In the afternoon Meira and me create a story out of random words cut out from the weekend magazine of our regular newspaper, the taz. There is a competition to win and it makes her practice her reading skills. We leave the house with inline skates to skate on a nearby school yard. It is cold and windy and the parks and streets are empty today. We meet our neighbours from downstairs whose son wears roller skates likewise; they tell me that they leave the house for the first time in 15 days. The mother says: ‘Now we know that we’re clean!’

There is an online demo between 4-6 pm under the hashtag #leavenoonebehind to show solidarity with those stuck in Greek refugee camps and demand that they be evacuated and taken up by Germany. Shortly after 6 pm I realise that this slipped my mind. I’m disappointed by myself. If this would have been a ‘real’ demo, I don’t think I would have missed it.

The rest of our day is spent like most Sundays: Meira takes a shower and over dinner we watch the weekly children’s series The Show with the Mouse.

Monday, 30 March 2020

Home schooling as usual; reading student papers, book reviews and writing emails while Meira is in the backyard with her friend Raya, her little brother, and their mother Vera. Picking her up, I hand over two material things to Vera that best describe my current everyday life. Vera is a visual artist and has started working on a photographic series of still lives with objects and short texts describing peoples’ lives during the Corona lockdown. In my case this is the pen that I use for marking essays and a slide box. The one I hand over to Vera contains rather old slides from my grandfather with metal framing and glass rather than plastic.

Shortly before noon a conference call with colleagues from our “Gender & Sexualities | Queer Anthropology” group. We were planning to write a joint piece on Queering COVID-19 (working title) but to my great regret I have to tell them that due to the lack of childcare I do not have the capacities to do so.[5]

In the meanwhile, the lockdown has officially been extended to at least April 20th but from listening to leading politicians on the radio and in talk shows it is already becoming apparent that this is not the end date yet.

In the afternoon I meet my friend Caro for a walk. Caro was offered a position several weeks ago, but her contract has not yet arrived. In the past few weeks, she was affected by a loss of earnings related to the cancellation and postponement of public events, which is why she decided to submit a request to access the “Rettungszuschuss Corona,” the Corona rescue package by the Berlin Senate offering up to 14,000 EUR of financial relief to the self-employed and tradespersons. She just submitted the request and received an email telling her that she is in the waiting line and that once it is her turn, she will have 35 minutes to fill in the online form. Her waiting number is above 10,000 and a little walking person moving forward rather slowly in a grey digital bar visualises her progress. During the afternoon a large number of Berlin friends post their ridiculously high waiting numbers on facebook. One missed his time slot for filling in the form and was waitlisted again, with a waiting number well above 100,000. At night my friend Caro has succeeded and been granted 5,000 EUR of relief aid. She perceives the procedure as overall rather unbureaucratic. The next morning the breakdown of the online platform for the request of the rescue package as well as its problems with data security have made it into the news of Radio Germany.

At night, we watch slides from my parents’ journey to Austria in the late 1960s.

Tuesday, 31 March 2020

The debate among the neighbours about the use of our backyard starts anew. Some are unhappy with the timing of the slots, others wish to spend time there both in the mornings and in the afternoons. Others still warn about being perceived as irresponsible by the neighbours. Conversations take place over the phone, in the backyard or upon meeting each other in the neighbourhood. Our self-set 2-households-maximum rule in the backyard doesn’t hold anymore and one of the neighbours invites us to another (virtual) meeting for discussion. She is in favour of a more relaxed usage of the backyard and in support of her position sends a link to Christian Drosten’s daily podcast.

Meira returns from the backyard with a bleeding wound. While climbing onto the garden hut, her leg got caught on a rusty nail. I disinfect the wound and try to take out the nail with a pair of tongs.

In the meanwhile, our field research trip to Turkey has sadly moved into an unknown and ever more distant future, with the situation in Turkey increasingly out of control. I write to the private school in Istanbul, where under normal circumstances Meira would have started school the following Monday and request that they return the tuition fees, several thousand Euros, that we had to pay beforehand in order to prove to Meira’s Berlin school that she will be schooled during our absence. To my great relief they refund the money within an hour. Over lunch we discuss what to do if the school closure continues until after April 20th. Ulaş will have to teach and if he still has access to his office at university he will go there for two days a week. Luckily, I still have the option to retreat to my private office which I share with Caro in a collectively-run cultural centre in Kreuzberg, the Mehringhof, on the remaining days.

At night a video conference with some of my colleagues from the University of Bayreuth. One PhD student from Ruanda is feeling ill and currently waiting for the result of his COVID-19 test. While he himself stays in Bayreuth, he tells us about the situation in Ruanda, talking to his family on the phone every day now. Ruanda has one of the strictest corona curfews in Africa. We talk about visiting parents over Easter; most will not but one PhD student says she will, no matter what.

Wednesday, 1 April 2020

In the morning, I talk to the person responsible for my work contract at the University of Bayreuth. She tells me that it has arrived and been dealt with, which is a great relief. As expected, I haven’t finished reading my Berlin students’ essays; nevertheless, the pile of essay to read is getting smaller. In the afternoon, I go for a walk with my friend Anna. We walk in the streets rather than beside the canal, because the sidewalk next to the canal is too crowded. We take note of the many flyers pinned on many front doors. Many shops have posted signs on their doors announcing delivery services. One group announces “Self-organization against the virus of control,” calling for civil disobedience and a collective sabotage of forced evictions in the neighbourhood. The flyer is published by a group that also publishes a blog which translates “solidly united against Corona”. It demands, among other things, an extension of health care services, the ongoing full payment of wages even in the case of temporary closures, a stop of forced evictions, full transparency of public measures as well as the freedom of movement and speech. Likewise visible in public space is a flyer by the local division of the Left Party with rather similar demands, including the demand for opening up empty hotels and offices for the homeless, refugees and those living in overcrowded flats. This makes sense to me. It makes me think of an empty hotel turned refugee camp in Nazareth that I visited many years ago as part of an anti-deportation network in Tel Aviv. While the media reported about refugees being accommodated in a ‘luxury’ hotel, I remember the hotel as a rather gloomy place, unfunctional for the needs of families and far from any kind of luxury.

I complete a survey by the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB) on the Corona Quotidian.

At night, instead of talking about the documentary film on Donna Haraway, a lengthy video conference with some of our neighbours about the usage of our backyard. We agree about sticking to the smaller groups but also about allowing two groups into the backyard simultaneously, as long as they stick to different corners. Our Italian neighbour Emilia looks worried and rather depressed; she tells us about her mother’s neighbours in northern Italy, who have been taken to the hospital with serious breathing problems. Also, due to the fact that her mother can no longer regularly visit, her grandmother has been moved to a care home with no one from the family allowed to visit.

Thursday, 2 April 2020

A message from Meira’s teacher has been forwarded to the parents’ WhatsApp-group: she asks all parents to encourage their children to read, work on the sheets she distributed and register in the online learning platform “Anton app.” We already did so a few days ago and Meira loves to work with the app. Since we usually restrict her access to videos, TV or digital games (she hardly ever plays online games except during holidays in Turkey, with her cousins), she is excited to be granted access to the tablet on a regular basis. I notice that she is extremely ambitious in completing the tasks given to her in the App. If she goes on to work on it for more than forty minutes, she gets increasingly tense. It is difficult to explain to her that she shouldn’t do too much and that an hour a day is more than enough. I still sit down with her to work with her exercise book and other learning materials. Most of all, we paint: on Monday, we attached a huge sheet of paper to the wall and sketched things that we projected on it with the slide projector.

The teacher sounds worried and according to her message out of 22 children only 9 have registered for the app, one week after she sent around the access information. In Israel and the US, we learn from friends, online learning platforms were also introduced but quickly cancelled after it became clear that not all parents (and children) have access to them. I’m quite sure that each of the children in Meira’s class has access to a tablet or computer with internet connection. However, some of the parents obviously neither had the time nor the inclination to register. The teacher also announces that she will invite some parents to individual meetings at the school, to discuss home-schooling.

At night, we watch slides again. My grandfather’s 75th birthday. I take pictures of some slides that show my cousin, who is now sick at home with COVID-19, and her mother, in an intensive care unit after a difficult cardiac valve operation. I send them to my cousin via WhatsApp, also asking how she feels. She replies that she is slowly recovering, but that her husband’s condition is unchanged. Their older daughter is also sick with fever. Neighbours deliver food to their front door.

Friday, 3 April 2020

The pile of student essays to read is slowly shrinking. I hope that once it’s gone I will be able to read at least some of the books on my long reading list, Rosi Braidotti, Esther Newton, Elisabeth Povinelli, and Mel A. Chen’s Animacies. I write to the publisher about the long-promised reviews of my book manuscript.

Like the previous week, I prepare two challahs but it turns out that my friend Yanai has already prepared challah by himself. He comes around to bring us some stuffed wine leaves that he prepared. They are delicious. Yanai is the first visitor we have had in weeks. He keeps his jacket on and stands next to the open balcony door, but we do have a glass of wine together while the challah bakes in the oven and Ulaş prepares dinner. Meira is excited and we have to repeatedly tell her to keep physical distance from Yanai.

I talk to my mum about a virtual Passover dinner the following Wednesday. Also, I talk to my uncle. His wife, my aunt, who a few weeks ago has had a difficult cardiac valve operation, has been moved from the intensive care to the palliative care unit of the hospital. This comes as a shock. For weeks, we’ve been receiving news about the progress of her health condition. These little progresses, reported to my cousin by a regular carer, were only half the truth, it now becomes clear. As my uncle tells me the news, his voice is shaking. I cannot imagine him crying and even the fact that his voice is shaking is difficult to reconcile with the image that I have of him. I remember the phone conversation we had after my father, his only brother, died. In spite of being audibly devastated by the news, his voice did not crack like it does now. Even though I’ve never been especially close to him, I feel like hugging him. I feel relieved when he tells me that his son is on his way from Hamburg with his wife.

Now that my aunt’s life is coming to an end, the hospital allows close family members in for visits. Accordingly, for the first time in the past three weeks or so, he was allowed to enter the hospital and see her this afternoon. As he sat next to her bad, talking to her and holding her hand, she dozed away. They will start treating her with morphine tonight and most likely, she will respond even less tomorrow. My heart aches for my cousin, sick with COVID-19, who might not be able to see her mom alive again. After the others went to sleep, I watch the news and the political TV comedy heute show. It doesn’t make me laugh today.

Saturday, 4 April 2020

It is a warm and sunny day. During a walk with a friend, neighbour and colleague at the University of Bayreuth, he tells me about the challenges of virtual teaching and we discuss the petition for a non-semester that we both signed about a week ago and the resistance the petition met from conservative and mostly male professors. Among them, a professor for Marketing and Service Management from our own university has publicly announced that the petition was ‘shameful’ and demanded that teaching staff should take on the ‘challenges’ posed by the epidemic, rather than engage in ‘petty accounting’ (kleinkarierte Abrechnungen, in German) in regard to their working hours. He obviously hasn’t properly read or understood the petition’s demands, namely to respond to the unevenly distributed care responsibilities and restrictions of movement among students and teaching staff. When I return home, Ulaş and Meira are out for a walk and it feels just wonderful to have the flat for myself. I continue reading Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble, which I started reading many months ago but never had the time to finish.

After an hour or so, I receive a text message from my cousin saying that her mom, my aunt, has just passed away in the hospital. I talk to my uncle. His son arrived from Hamburg and they were still able to see her in the morning. Due to the morphine she started receiving last night, she was no longer able to fully recognize or respond to them. That is truly sad news. I feel like traveling there, but due to the fact that visiting restrictions are in place and the date for the funeral is not yet set, it doesn’t make much sense. I feel with my cousin who due to her COVID-19 infection was unable to see her mother alive one final time. At least, she and her husband are slowly recovering from the infection. After dinner, I tell Meira about her beloved grandaunt’s death and we light a candle for her. Having lit candles for her deceased grandfather and my mother’s dog in the past few months, Meira wonders out aloud: ‘Who’s next?’

Sunday 5 April 2020

Under normal circumstances we would have left for Istanbul for four months today. We managed to return our flight tickets (the flights were cancelled), but are still waiting to receive the deposit that we already paid for the flat. Our landlady, who rents out several flats via Airbnb, is desperate, because these days everyone cancels their visits. She says that she will pay us back later. While still in bed, I read an interview in The New Yorker on the situation in Turkey, which confirms much of what we heard from friends and Ulaş’ parents in Turkey. Even though Turkey is now among the top ten of countries with confirmed cases of COVID-19, there still is no lockdown in Istanbul. The situation in the UK is even worse. Many of my friends from Manchester (where I lived for almost two years between 2007–9) have self-quarantined several weeks ago. I worry about Inesh, a friend from Berlin, who lives in London and works as a medical doctor in a university hospital.

It is a warm and sunny day and I join Meira into the backyard with a book. However, she asks me to leave –she obviously enjoys being on her own during her daily hour or two in the backyard. After lunch, we leave for the Tempelhof Airfield. At the entrance, teams of security personnel distribute flyers. Among other things, these ask visitors to keep a distance of at least 1.50 metres from each other and refrain from sitting together in larger groups or having barbeques. If visitors violate these rules, the flyer says, the airfield might be closed. This is unimaginable today, with tens of thousands of residents flocking to the former airfield with bikes, inline skates, kites, wind skateboards and all kinds of means of transportation. On the way back home, Meira asks for a Shawarma. While helping her to remove her inline skates, Ulaş leaves the bag with her braces on the sidewalk. At night, he returns to look for it, but only finds the empty bag.

I also read out the Passover story to Meira and we listen to some Passover songs on Youtube. Passover Eve is on Wednesday and while we’re not too serious about celebrating Jewish holidays in the family, we are planning to have a joint celebration via Zoom.

Monday, 6 April 2020

The pile of student essays to read on my desk is shrinking, a few more to go. I read a field research report from my PhD student in Napoli, who works on tattooing in the city. On March 9, he recounts how people still kiss each other on the cheek as a way of greeting and only after March 10, the first tattoo studios in Napoli closed their doors.

Today, it’s even warmer than yesterday and after lunch I take Meira to a nearby garden centre by car to buy plants and potting-compost for our balcony. I’m shocked to see that the garden centre is packed! I try to leave as quickly as I can, but Meira hasn’t been to any shop in a long time and is difficult to get out of there. After planting, we print out flyers in the hope of getting Meira’s braces back (“Lost braces! Finder’s reward 20 Euro!”).[6]

While Ulaş and Meira distribute the flyer, I receive a message from Inesh, our friend in London. He writes that ‘things are getting worse here. These idiots [he obviously means the conservative government under Boris Johnson] shrug off death as if it was some inevitable natural catastrophe. Three of my patients died from COVID. As did two of our staff. I feel like screaming but I’m too depressed. There’s a 70% mortality rate in our intensive care unit, because patients are admitted when it’s already too late. I take my hat off to what is happening in Germany.’

After reading the message, I have to sit down. I stare into nothingness for a while. While we sit at home and go for a walk or shopping once in a while, in many hospitals in the world, there is an unimaginable struggle going on. I worry about my friend. I call my uncle and cousin. She and her husband are slowly recovering from the infection, but still unable to leave the house. Her mother, my aunt, will be cremated tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, which allows them to postpone the funeral service until after my cousin is free to leave the house again. Current regulations allow only up to five funeral guests, so given the fact that my aunt’s brother will also want to participate, I will not be able to attend the funeral.

Tuesday 7 April

Home schooling Meira, reading student essays and responding to emails in the morning. In the afternoon, Meira’s friend Raya, the one she continues to play with in the backyard, comes to our place and we decide to make a cake. The two girls skim through our cooking books and opt for a strawberry cheesecake. We leave for the small organic food store around the corner to buy the ingredients for the cake. Since about one week, a sign on the entrance announces that only three customers are admitted to the store at the same time. A large plexiglass pane separates between the customers and the salespersons. On our way back home, I meet my friend G., who teaches at the American University of Cairo. It’s been a long time since we last met! We wave at each other from a safe physical distance. She returned to Berlin even though the semester is not yet over. She feels safer in Berlin and reasons that she can do the online teaching from anywhere. The strawberry cake is tricky, but the girls have fun. The cake has to rest in the fridge overnight.

At night, I watch a short BBC documentary of my friend’s intensive care unit in London. The doctors and nurses act in a calm and self-composed manner, but they also talk about incredibly long shifts, infected colleagues, of patients dying. Wearing protective clothes for long hours each day must be straining, not to mention the stress and the fear of losing one’s patients and colleagues… In the report, there is a scene of an entire team of doctors and nurses turning a sedated corona patient. This scene continues to haunt me and I continue to see it in my mind’s eye over and over again.

Wednesday 8 April

The university’s public relations department is looking for someone to talk to a public television team about shaking hands. After some deliberations, I agree. The responsible journalist requests to do the filming at home and for a moment I regret having accepted the request. I try to explain that I currently work in a corner of my bedroom, but she assures me that they will choose the angle carefully. I take this as an opportunity to clean the flat. Today is also the day before Passover, which in many Jewish families is a day of intensive spring cleaning, so it makes perfect sense to clean. There’s a number of boxes with books and slides and films from my deceased father’s house that I try to run through as fast as I can. Most boxes disappear into the basement. Some stuff from the basement goes into the car to be taken to the municipal waste disposal site one fine day. In the afternoon, we take the strawberry cheesecake that I did with Meira and Raya the day before to be eaten in the backyard. Meira and her friend distribute pieces of cake to the other neighbours in the garden, with small groups sitting in different corners (zealously trying to keep physical distance while doing so); within a few minutes, the cake is gone. It was delicious and the girls are very proud of themselves.

In the afternoon, I go shopping at a larger supermarket to get things for our Passover meal. I hope to find Matzo there, the unleavened bread used for Pessah, but it is sold out. For the first time since the coronavirus outbreak, I take a facial mask with me. Up until now since the lockdown, I completely avoided larger supermarket or the neighbourhood shopping mall, buying things in the smaller and usually empty organic food shop around the corner. Wearing the facial mask feels weird. Sweaty and warm. I cannot imagine working for hours with this thing on. It is difficult to talk and I feel visually impaired. Also, I can feel people staring at me and realise that still only a small minority is wearing face masks.

At night, we celebrate the Seder, the ritual dinner on the first night of Passover, with crisp bread instead of matzo and with a painted Seder plate instead of the ceramic plate that we usually use (it is at my mother’s house). The rest of the family present via zoom. We light an additional candle for a family friend, who died aged 73 in Italy the day before. He suffered from a serious kidney damage for several years and has recently refused the dialysis treatment. We wonder whether the threat to be infected with the coronavirus was part of his decision.

Thursday, 9 April 2020

After home schooling, Meira and Ulaş leave the house and I get ready for the TV interview.

The TV team arrives with three persons, the interviewer, a camera man and someone for the sound and the light. They wear face masks and are very careful not to touch anything. Welcoming them into the apartment is awkward and I joke that we probably shouldn’t shake hands now (they come for a report on (not) shaking hands). It is difficult to keep physical distance in the corridor of our flat. I explain that we could do the interview in front of the bookshelves in our living room or in the bed room, where I usually work. The cameraman prefers the bed room because of the light. It feels rather strange to give an interview for Germany’s Channel 1 main news show in my bed room. The journalist borrows a pen from me and before returning it she disinfects it with a liquid that she carries in her handbag. Before leaving, the cameraman gazes into our backyard and sighs that he envies us for it. I tell him that I do realise how lucky we are. He says that he takes his kids to an allotment garden outside of the city over weekends.

I somewhat enjoy the conversation and the time passes quickly. Nevertheless, the interview leaves me somewhat unsatisfied, since nothing of what I said is based on my own empirical findings really. Also, I feel that anyone could have said what I said. At least the event made me clear up the flat!

In the afternoon, I go for walk with my friend Elza, a social worker employed in a social welfare organisation supporting Eastern European minors living on the street in Berlin. Elza continues to work. She is not sure how the epidemic so far has affected the people she serves. Some of them squatted an empty building, others started sleeping outside in order to avoid the shelters (some of which refuse to host any newcomers these days, due to fears of spreading the coronavirus), but also, because the weather increasingly allows them to. Elza makes fun of the mayor’s letter to all Berliners, which we also had in our mail box the day before. As if “It is difficult for all of us” and “The streets are empty these days,” she says. In contrast, the effects of the lockdown affect different groups of people quite differently in Berlin, she says, and at least in Kreuzberg and Neukölln where we now walk beside the Landwehrkanal this sunny afternoon, streets are rather crowded. The letter had his picture and a personal address on one side and information on the coronavirus regulations and emergency numbers and addresses of testing stations and help for those affected by domestic violence or quarantine-related anxieties on the other. At night, I suffer from a terrible headache. Is this an effect of the tension caused by the TV interview, or simply a sunstroke?

Friday, 10 April 2020

Today is Good Friday, a public holiday, but these days every day is as calm and quiet as it is today. Except for the birds in our backyard chirping from about 5 am in the morning, much louder than they ever did before the lockdown, it seems to me. While Meira plays with her friend Raya in the backyard, I write a letter to our institute’s board of examination explaining a suspected case of plagiarism. This is not a pleasant thing to do and while I write, I repeatedly check facebook. A British friend of mine posted an article by the Guardian titled “UK will have Europe’s worst coronavirus death toll, says study” and commented it the following way: “It was nice knowing y’all. I hope to survive as working very hard to build up a strong immune system through yoga, good music, and diet, but if not… it was fun sharing, liking and showing solidarity in this space!” I know she is being at least partially ironic, but probably also worried, having been in self-quarantine since mid-March in her flat in Manchester. Others scandalize the fact that the effects of the coronavirus are unequally distributed in the US, with poorer families and Black Americans being hit much harder in terms of both health and economics. I also read a BBC article on the increased use of Eau de Cologne in Turkey due to its disinfecting qualities. This relates so closely to my envisaged research project on smell and scents that in a funding proposal I tentatively called the “Olfactories of Beauty”! Will we be able to leave for Turkey before the winter semester begins? Perhaps I should shift my research interest and study the use and new connotation of Eau de Cologne in Corona times? In the past few days, as the number of student essays started to dwindle, I began reading into the anthropology of smell and the history of perfumes. I can’t remember having come across anything on Eau de Cologne and indeed, this starts to catch my interest.

In the evening, we take a short walk with Anna, who returned to work in the book store on Monday. She tells me that the store is at least as busy as it used to be before the lockdown and that in addition, they also started delivering books. This afternoon, on her way back from the book store she delivered a book to a regular client, who has been in self-quarantine since March 7. Over the phone he told her that he hasn’t left the house even once ever since. She dropped the book in his mailbox and was sad to see that the house didn’t even have balconies.

At night, the Turkish government announces that there will be a complete lockdown with all stores closed over the weekend. As soon as this piece of news is out, hundreds of thousands take to the street to go shopping. On Twitter, we see pictures of incredibly long queues in front of supermarkets in Istanbul. Someone posts a picture that shows how in front of the supermarket next to the house that we rented in Moda, Istanbul, there is a 1-kilometre long line. On other streets and public squares large groups of people mingle often shouting at and pushing each other.

Saturday, 11 April 2020

Right after breakfast I go grocery shopping, with my facial mask on. Also, I take my bike for repair in a bicycle shop. From a friend who owns a bicycle shop in Kreuzberg I know that bicycle shops are packed these days, because it is spring and many are re-discovering their bikes during the lockdown. However, I’m the first client today and am lucky to be able to pick up the repaired bike on my way back from shopping. When I enter the market around the corner from our house, the check-out line winds through half of the market. I take the last box of eggs; flour and yeast are out as usual. In the afternoon, Meira discovers an App by the Show of the Mouse and I finish reading Donna Haraway’s book.

The sudden lockdown in Turkey is on the German news; commentators and political opponents speak of an irresponsible and contra-productive crisis management. Nevertheless, the Turkish president continues to rely on the ongoing support of his many followers. From what we hear via twitter and the Turkish news, every citizen aged 65 and above will be given a coronavirus emergency kit including face masks and kolonya, Eau de Cologne, which has recently seen a revival due to its disinfectant effect. My Turkish friend in the UK ordered a litre of kolonya. According to Turkish news reports many people in East and Southeast Asian countries likewise ordered kolonya from Turkey. When I conceptualised my research project on the everyday uses of scents and fragrances in Turkey almost one year ago, I could never have imagined its sudden relevance and change of meaning.

Sunday, 12 April 2020