Rethinking Collaboration in Social Anthropology

Co-Producing Knowledge Outside Boxes

Introduction

The shift from extractive to collaborative models of knowledge production is about redefining the ethics and politics thereof, especially in North–South relations, interdisciplinary research, and policy engagement. This blog post aims to critically discuss academic co-production of knowledge and how it could be understood within the process of knowledge co-production in social anthropology and African studies. At the center of balancing respective epistemologies and establishing complementarity in co-production lies a question: How do collaborating scientists with different senses of place and being claim they collaborate in ways they believe make the world intelligible? This epistemological question must be given thorough consideration. We refer to this question as thinking outside the academic boxes to reshape collaboration. Though we aim to analyze Global North and South academic relations, our ideas in this post relate more to Africa. Balanced collaboration in this context denotes the condition and process of co-production that acknowledges epistemological differences between collaborators and accords the same level of recognition and value to each collaborating actor. We see balance here as entangled with heterarchy, which Klute (2013) defines as a non-hierarchical and plural distribution of power. In this sense, authority of co-production is not centralized in the donors’ side or the field but is dispersed across overlapping institutions and actors.

Our reflections on this topic started within the regional group Africa of the German Association of Social and Cultural Anthropology when one of the authors of this work, Lamine Doumbia, participated in a May 2024 workshop at Humboldt University Berlin on South-North academic collaboration. This reflection continued through the co-organization of a panel concerning the possibility of redesigning South-North research partnerships at the 2024 Association for African Studies in Germany (VAD) conference.[1] Together, the co-authors of this work draw on our research experiences to contribute this piece and advance a balanced knowledge co-production paradigm. Dealing with knowledge production, in whatever form, can be done more fruitfully through collaboration and co-production.

Knowledge production thrives when collaborative and individual efforts are seen as complementary rather than opposed. Collaboration draws on participants’ complementary skills, ideas, experiences, epistemologies, and other resources. Collaboration broadens and deepens research, while individual effort can sharpen and personalize it. This requires an extremely careful, holistic approach to establishing equitable relations that must also look beyond academia. In addition to equity, there are at least five other arguments in favor of collaborative knowledge co-production: strengthening all countries and participants in their ability to solve problems and transform, greater efficiency in research, strengthening rules-based global cooperation, building trust and mutual understanding, and promoting a better positioning in the “competition” with other countries for cooperation partners (Djenontin and Meadow 2018).

The Africa Charter for Transformative Research Collaborations is an African Union initiative that aims to strategically ensure balanced co-operation in knowledge production.[2] If collaboration is to be more than the coordination of some actors by others—if it is to be co-creation—then equity and balance are not just ideals; they are the very conditions that make collaboration relevant and just. The charter is based on the rationale that a rebalancing of collaborative structures is essential for Africa and the global community (Aboderin et al. 2023) and it sets a moral and intellectual baseline for doing so. Critically, it may not spell out exact procedures, but it makes clear that any meaningful collaboration must take seriously and address the multiple axes of inequality, epistemic, institutional, linguistic, and material, that have historically shaped knowledge production in and about Africa. Moreover, when collaboration in knowledge production is evaluated solely within academic contexts and through academic perspectives, the contributions of non-academic actors go unrecognized, while the North–South divide restricts the scope of this understanding. (Molosi-France and Makoni 2020).

In terms of collaboration, it is essential to clarify its strands under consideration. This reflection touches not only on academic–academic partnerships, but also on collaborations that cross boundaries: between academia and non-academic actors, across Global South–Global North divides, and between disciplinary and epistemic traditions. Each of these strands brings its own set of challenges. Moreover, when they intersect—as in, for instance, a transdisciplinary research project involving Global North universities, African grassroots organizations, and policymakers—the complexity multiplies. In such constellations, balance for complementarity in collaboration cannot be addressed solely through fair funding distribution or co-authorship; it must also grapple with epistemic legitimacy, cultural translation, and differentiated access to power. Therefore, while this discussion refers broadly to collaborative research, it particularly focuses on multi-scalar, cross-sectoral partnerships in which questions of equity and balance are most pronounced and politically charged.

Concerning the how and why of academic collaboration, that is, disciplinary differences and policy implications, Lewis et al. (2012) argue that it makes sense to distinguish between collaboration (lowercase c) and Collaboration (capital C). The thinking behind this is that almost all academics, whether we recognize it formally or not, embrace collaboration with the lowercase c through discussion and sharing of ideas. Collaboration written with a capital C, towards which we lean in this post, is the formal kind where academics in the Global North and South (together with non-academics where circumstances permit) apply for grants together, conduct research together, write papers together, and are collectively responsible for outcomes. In the process of co-producing knowledge, balanced collaboration holds high prospects for legitimately co-produced knowledge, now and into the future. Terms such as cooperation, collaboration, inclusive collaboration, and co-production are not interchangeable. They mark different levels of integration, power-sharing, and epistemic commitment in an “unbalanced” world. While cooperation may involve coordinated efforts with limited mutual engagement, co-production demands that all actors—academic and non-academic, Global North and South—participate in shaping the entire research process. Achieving this is an ethical imperative, but how can collaborative relations be balanced? In a heterarchical process, co-teaching, co-supervision, co-applications, co-authoring, co-publication, and so on are not new and these are very effective techniques.

Why is Balanced Collaboration Necessary?

Balanced and fair collaboration is essential for producing knowledge that draws from the complementarity of all epistemologies and efforts and that is credible, relevant, and insightful for all actors involved. In contexts of knowledge co-production in social anthropology—a field marked by colonial legacies, global inequalities, and disciplinary hierarchies—balanced collaboration is definitely corrective. However, collaboration and the benefits of co-producing knowledge are not necessarily uncontroversial. For instance, the desire to forge collaboration for knowledge co-production could provide grounds for undue influences and pressures from institutions and funders with power. . For decades, researchers and research institutions in the Global North have relied on their counterparts in the Global South to conduct research activities in a collaborative and cooperative framework. However, this collaboration and cooperation are often defined based on the epistemic frameworks of the Global North; researchers from the Global South are relegated to being consumers of the research design and implementers of the research activities on the ground. Those outside the academy are even more marginalized and often instrumentalized merely as sources from which to extract knowledge (extraction in this context means researchers, oblivious of their own epistemic limitations, assume hegemony over knowledge). Yet, we contend that communities hold knowledge from their own lives, and researchers contribute to making such knowledge intelligible to the world beyond these communities. This makes it crucial for knowledge co-production to consider communities as complementary actors at all stages of the process.

When colleagues from the Global South engage in activities such as organizing workshops or conferences and collecting empirical data for the needs of researchers from the North, standards based on the norms and misrepresentations of the Global North are imposed on the collaboration. For instance, funding proposals often assume African institutions do not have the capacities to manage collaborative research or conference funds even if such research or events occur in Africa. Moreover, there are ethical clearance institutions at almost every university in Africa that certify research collaboration between the Global North and Global South, but it is not uncommon that ethical clearance for research in Africa is only deemed certified if approved in the Global North. In this context, how can an institution located in the Global North, quite isolated from communities in the South know what breaches the ethics of the societies under study? Ethics is grounded in and best explained by ontological and epistemological values in particular contexts. Epistemological differences between the Global North and Global South must be acknowledged, respected, and tolerated in knowledge co-production. This goal can be achieved by reconfiguring knowledge co-production through a heterarchical model—one that values diversity of knowledge, fosters horizontal collaboration, and resists hierarchical dominance.

Acknowledging Epistemic Limitations Enhances Collaboration

Knowledge co-production is strengthened when researchers, funders, and communities are critical of the status quo and acknowledge their own limitations. Such acknowledgement leads to open-mindedness on the part of researchers. Scientific collaboration and knowledge co-production between researchers and societies in the Global North and Global South must thus begin with the recognition of epistemological and conceptual differences—differences that must be acknowledged, respected, and navigated with care (DePuy et al. 2022). Value in such collaborations is not inherent but constructed through mutual engagement, dialogue, and the willingness to learn from one another.

How do we determine what counts as beneficial, sound co-produced knowledge and what does not? Current approaches to scientific collaboration, which are often touted as beneficial for all researchers despite positioning Global South scholars as mere data gatherers, are an exercise in the denial of hegemony that does not help genuine co-production of knowledge. In such projects, Global North scholars typically serve as Principal Investigators and control funds and research collaboration with African researchers, leaving the bulk of empirical work to their counterparts in the South.[3] Against this background, North-South partnerships have evolved in recent years from a normative framework to individualized or personalized collaborations.

In what is referred to as the ‘The African Genius’ speech to formally open the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana in 1963, Kwame Nkrumah, the then President of the Republic of Ghana, cautioned against African intellectuals adopting concepts from non-African societies to understand the world of Africa. He also advised non-African intellectuals willing to stay and work in the Institute of African Studies to acknowledge the limitations of their epistemic frames and discard their own biased epistemologies and notions about Africa in order to study the continent from within its own conceptual categories.

In our view, knowledge is about making a community or a certain event intelligible to the world outside. What we claim to be knowledge is, in fact, some form of conceptual category that researchers impose on the world. It is thus only a construction of the object of study (Mudimbe, 1988) but different epistemologies construct the object of study differently. One of the major questions addressed by Diawara et al. (2022) “is the claim that the conceptual apparatus (colonial library) of the social sciences and the humanities has not been able to recover African experience because of the failure of scholarship to acknowledge the role of context in rendering concepts meaningful”(11). Societies around the world already possess their own conceptual categories, vocabulary, and maps, all of which outsiders, even in collaborative knowledge co-production, must acknowledge, respect, and tolerate. As Elísio Macamo insightfully argues in a personal conversation, quoted by Derichs et al. (2020), we must distinguish between a “Eurocentrism of origin” and a “Eurocentrism of application”—a critical distinction that twists the knife in the wound of global knowledge production. While many theoretical frameworks originate in European contexts, their application beyond those contexts often goes unquestioned, reinforcing hierarchical epistemologies. This becomes especially pertinent when we consider efforts to balance the co-production of knowledge with the imperative to think outside the box. Derichs et al. (2020) have emphasized the importance of creating academic spaces that are genuinely dialogical, where epistemic partners from different regions can contribute. Yet, the challenge remains: How can knowledge be co-produced when one side’s intellectual traditions are systemically privileged over another’s?

Illustrating Collaborative Knowledge Production

Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA)

While the pressure for collaboration—particularly across institutions, disciplines, and global regions—has sometimes emerged from external funding demands, it would be misleading to view this as merely instrumental. In fact, these pressures have had productive effects, pushing researchers to explore new areas, apply methods across disciplinary boundaries, and engage with different challenges in ways that have led to relevant impact. There is also empirical support for the idea that collaboration itself enhances productivity. Landry et al. (1996) show that researchers involved in collaborative work tend to produce more. Yet beyond productivity, the deeper value of collaboration lies in its potential to foster inclusive and co-produced knowledge—especially when it is intentionally designed to challenge hierarchies and redistribute epistemic authority.

An illustrative case is the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA) at the University of Ghana. MIASA is jointly led by a German and a Ghanaian director, reflecting a commitment to institutional balance and shared leadership. One especially notable example of collaborative knowledge co-production was the conference of the Interdisciplinary Fellow Group 6 (IFG 6), which ran from May to August 2022. Titled “Land Governance in West Africa through Interdisciplinary Empirical Lenses,” IFG 6 included scholars from both West African and European institutions—Peter Narh from Ghana, Lamine Doumbia from Germany, Aly Tounkara from Mali, and Austin Dziwornu Ablo from Ghana—working together across multiple terrains and institutional settings (Doumbia and Narh 2024). This collaboration also extended beyond academia; research was conducted with and within diverse institutions and communities, including customary land secretariats, land commissions, traditional authorities, and grassroots residents. These actors were not just subjects of research; they were engaged as knowledge holders and contributors, and some were invited to the final conference as practitioners, illustrating a co-productive model of research grounded in mutual learning. The research findings made clear that reflexive, locally grounded methodologies—what was described as Sankofa,[4] involving endogenous values and knowledge—are essential for navigating complex land governance issues with outcomes for communities that are becoming yet more complicated due to digitalization of land governance and administration. This approach made clear that academics, communities, and practitioners must collaborate in order to formulate flexible governance strategies that can adapt to changing land tenure systems.

The MIASA collaboration also gave rise to the 2023 Point Sud conference, co-developed and implemented by Peter Narh, Lamine Doumbia, Thrung Thahn Nguyen, and Andrea Behrends, again from academic institutions in Ghana and Germany. The conference centered on digitalization of land governance in Africa and its outcomes for social groups. The collaborative agenda benefitted not only the quality of research, but also the researchers’ professional development through opportunities to improve leadership, communication, project coordination, and the ability to work across disciplines and cultures. This collaborative experience highlights the importance of aligning practice with evolving international standards for balanced collaboration. As Lamine Doumbia noted in conversation with Hans Peter Hahn, documents such as Germany’s UNESCO position paper and frameworks like the Africa Charter and the TRUST Code affirm the principle of cooperation “on an equal footing.” This norm, though widely endorsed in policy, must still be operationalized through everyday decisions in collaborative research—from authorship and leadership structures to data sharing and community engagement.

Point Sud Centre and Capacity Development of Researchers in/from Africa.

The Point Sud Centre for Research on Local Knowledge is a concrete example of diachronic and resilient transregional collaboration. The Point Sud Centre was founded in November 1997 by research fellows from Mali and has many years of experience in supporting researchers and students from the Global North and South. Since the beginning, master’s students, PhD candidates, and postdoctoral researchers from Europe, the USA, Canada and Africa have been hosted through partnerships to enable them to conduct field research, organize seminars, and participate in conferences and workshops. Against this background, the Centre has established several research networks on the African continent (Senegal, Burkina Faso, Gabon, Mozambique, Ghana, South Africa) and beyond (mainly with German research institutions, foundations, and universities) that facilitate scientific exchange and cooperation between researchers in and from Africa on various topics worldwide. Point Sud programs have contributed significantly to reducing inequities in knowledge co-production. For example, a classic program entitled the Point Sud Programme is financially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Each year, it issues a call for applications to organize scientific events of any kind in one of its network locations on the African continent. The applicants for the organization of the workshop are required to be a mix of researchers from the North and the South who are responsible for developing a call for papers or panels and selecting the participants. The Point Sud Programme organizes an average of six international scientific conferences per year. The scientific events are attended by scientists (emerging and established), universities, practitioners, policy makers, artists, and writers. In Mali, for example, while there are strong research traditions in certain fields (e.g., law, history, anthropology, development studies), the lack of state funding and unstable political climate limit the ability of institutions to retain talent or lead sustainable international partnerships on their own terms. This makes the efforts and resilience of Mamadou Diawara (the founder of Point Sud), his colleagues, and his students particularly noteworthy.

We acknowledge that Point Sud funds are from the Global North and that this creates some complications as well as reservations on the part of researchers and institutions from the Global South. The reliance on Global North funding, particularly from the DFG, may be a source of power imbalances in funding administration, revealing persistent structural inequalities. Despite these challenges, Point Sud emphasizes the importance of locally led initiatives, mixed leadership, and inclusive formats that bridge scholarly and practical expertise in the social sciences and humanities. The Point Sud experience thus teaches us that genuine collaboration requires not only dialogue but also structural change in funding mechanisms and institutional power relations.

Conclusion

We have laid out a heterarchical model for collaborative knowledge co-production. This is where epistemological differences of researchers from the Global North and South are acknowledged, respected, and drawn on for complementarity as part of a balancing effort to co-produce knowledge. We note that this heterarchical model also acknowledges that researchers are not hegemonic producers of knowledge per se. Rather, apart from researchers, communities and practitioners also hold a wealth of knowledge that complement that of researchers in making the world intelligible. Our heterarchical approach promotes the paradigm that beyond concerns about where research or academic funds are obtained for collaborative work, the legitimacy of the ensuing research lies in complementing efforts, including recognizing contexts within which divergent epistemologies and ethical norms in research and other academic works should be acknowledged and respected. Global South entities must also strive to independently meet some of their research funding needs to complement funding from external sources, to strengthen balanced collaboration. Knowledge co-production must move beyond thinking in terms of mere cooperation and recognize the need for a more fundamental rebalancing of the relationship between Africa and the Global North and their respective positions in the global science and research ecosystem. The goal must be for African scientists, African higher education and research institutions, and the knowledge produced on the continent to take their rightful place in the global scientific landscape.

The principles laid out in the Africa Charter and the UNESCO position paper—balance, inclusion, and rebalancing—are not abstract ideals. They find relevant application in projects such as the Interdisciplinary Fellow Group 6 (IFG6) at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA) and the Point Sud programs. As discussed earlier, IFG6 exemplified many of the core principles outlined in these international frameworks. The group was co-convened by African and European scholars, conducted research across diverse field sites in Ghana, and included a broad range of local stakeholders—from traditional authorities and land commissions to community members. The project did more than gather data because it co-created insights, engaged practitioners and communities in knowledge exchange, and directly contributed to new initiatives like the 2023 Point Sud conference in Accra. The Africa Charter for Transformative Research Collaboration, which has recently been ratified by several universities and research institutions, is a very important framework for creating awareness among African researchers and institutions to actively work towards balance and complementarity in their collaboration with colleagues in the Global North as part of a heterarchical model.

References

Aboderin, I., D. Fuh, E. B. Gebremariam, and P. Segalo. 2023. “Beyond ‘Equitable Partnerships:’ The Imperative of Transformative Research Collaborations with Africa.” Global Social Challenges Journal 2 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1332/27523349Y2023D000000002.

African Academy of Sciences. (2023). Africa Charter for Transformative Research Collaborations. Nairobi: AAS.

Calkins, S. 2023. “Between the Lab and the Field: Plants and the Affective Atmospheres of Southern Science.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 48 (2): 243-271. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211055.

Diawara, Mamadou, Mamadou Diouf, and Jean-Bernard Ouédraogo, Jean-Bernard, eds. 2022. Afrika N’Ko: La bibliothèque coloniale en débat. Présence Africaine.

DePuy, W., J. Weger, and K. Foster et al. 2022. “Environmental Governance: Broadening Ontological Spaces for a More Livable World.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5 (2): 947-975. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211018565.

Derichs, C., A. Heryanto, and I. Abraham. 2020. “Area Studies and Disciplines: What Disciplines and What Areas?” International Quarterly for Asian Studies 51 (3–4): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.11588/iqas.2020.3-4.13361

Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission. (2024). Gleichberechtigte Wissenschaftskooperation weltweit – Positionspapier der Deutschen UNESCO‑Kommission (54 pp.).

Djenontin, I. N. S., and A. M. Meadow. 2018. “The Art of Co-Production of Knowledge in Environmental Sciences and Management: Lessons from International Practice. Environmental Management 61: 885–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1028-3.

Doumbia, L., and P. Narh. 2024. “General Introduction: Land Governance and Conflict in West Africa through Interdisciplinary Empirical Lenses.” In Land Governance and Conflict in West Africa through Interdisciplinary Empirical Lenses. MIASA Working Paper No. 2024(1): 5–9). University of Ghana. https://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/server/api/core/bitstreams/69671478-4a61-4bb3-90c3-a894dfea3580/content.

Klute, G., and A. Bellagamba, eds. 2013. Beside the State: Emergent Powers in Contemporary Africa. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Landry, R., Amara, N., Lamari, M., 1999, Utilization of Social Science Research Knowledge in Canada, Research Policy, 30(2): 333 –349.

Lewis, J. M., S. Ross, and T. Holden 2012. “The How and Why of Academic Collaboration: Disciplinary Differences and Policy Implications.” Higher Education 64: 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9521-8.

Molosi-France, K., and S. Makoni. 2020. “A Partnership of Un-Equals: Global South–North Research Collaborations in Higher Education Institutions.” Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society 8 (2): 9–24. https://doi.org/10.26806/modafr.v8i2.343.

Mudimbe, V. Y. 1988. The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Indiana University Press.

Nkrumah, K. 1963. “The African Genius” Address, University of Ghana, Institute of African Studies, Accra, Ghana, October 25, 1963.

TRUST Consortium. (2020). Global Code of Conduct for Equitable Research Partnerships. European Commission, Horizon 2020 Project TRUST.

[1] https://nomadit.co.uk/vad/vad2024/programme.phtml#13847

[2] https://bpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/1/627/files/2024/05/Africa-Charter-web-new-cover-52e5a047925be9dc.pdf (accessed 04.04.2025)

[3] Calkins (2023) highlights research hierarchies in bioengineering, providing an example of Ugandan scholars being reduced to data collectors. This supports our thesis beyond African studies and social anthropology.

[4] The term Sankofa in this context refers to our efforts to embrace and value as complementary to ours, the epistemologies, beliefs, and experiences that endogenously evolve from communities in which and with whom we conducted our study.

Dr. Lamine Doumbia is scientific staff (Assistant professor) for African History at Institute for Asian and African Studies – Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. As a social and cultural anthropologist, he completed a postdoctoral researcher at Excellence Cluster “Africa Multiple” of University of Bayreuth. Previously he completed two fellowships and at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa – University of Ghana Legon. Doumbia was also a postdoctoral fellowship at the German Historical Institute Paris (DHIP) and Centre de Recherches sur les Politiques Sociales (CREPOS) – Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar.

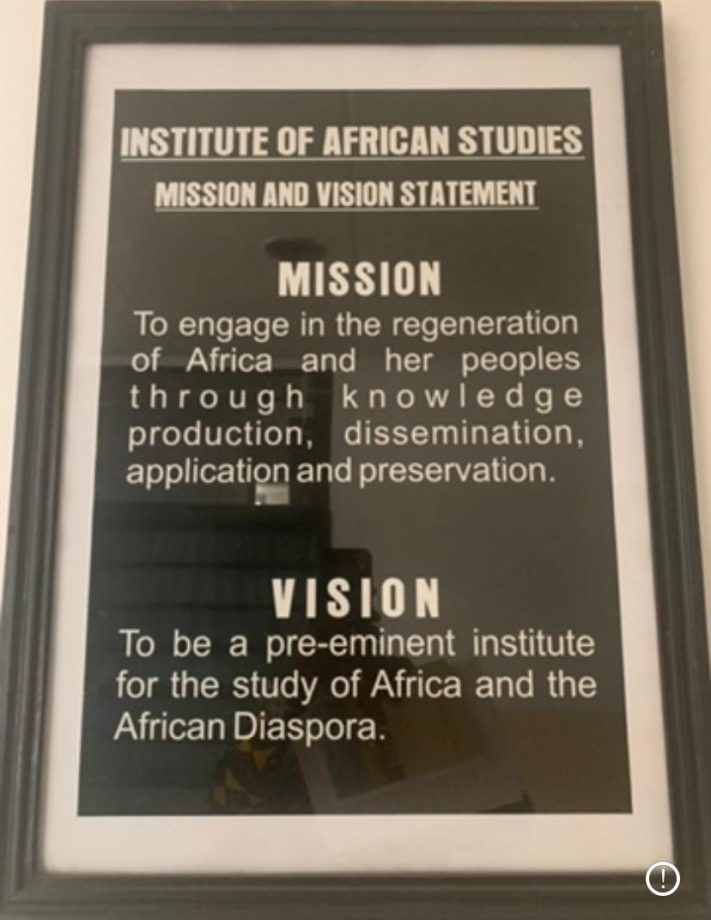

Dr. Peter Narh is an Environmental Social Scientist and at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana. He researches African land and natural resources conservation and governance. Currently, his research focuses on social formations and viability in environmental resources governance in Ghana and Kenya. He holds a PhD in Development Studies (Environmental governance option) from the University of Bayreuth in Germany. Affiliation: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, pnarh@ug.edu.gh

Dr. Drissa Tangara is a Sociologist of Education with a focus on AI and Technologies’ Impacts on Learning Process in Higher Education at the Insitut de Pedagogie Universitaire (Bamako/Mali). Besides, he is a G.E.S. 4.0 Awardee from University of Johannesburg, the Leading University in 4iR and AI in South Africa where he is affiliated to Community Adult Workers’ Education (CAWE), University of Johannesburg. His research expertises focus on Edtech and digitization of Governance, Political Economy of AI, Social Media & Social Movements, and Unionism in the time of AI. He has been involved in some research programs at Point Sud as a part- time researcher in recent years.