Co-Work

Reflections on the Search for Research Practices with Returned Ghanaians

Abstract

This piece asks: How does the linkage between how we know and with whom we know design research practices? What does it imply if we center inequalities and authorities in the research process and search for ways of working together out of reflections on these dynamics? Drawing on the research process with Ghanaians who were forcibly returned from Germany to Ghana and labelled as “returnees,” this contribution highlights the search for research practices in the context of a violent border regime and subsequent mobility inequalities. By thinking with the co-work with three interlocutors and our various ways of engagement—through audiovisual forms, co-writing, and reflections on documents and objects—I show how diverse artifacts and multimodal forms became significant in processes of co-producing knowledge. Overall, the piece suggests thinking about the ethnographic encounter as an experimental search that takes people’s own interests, expectations, ways of expression, and levels of commitment seriously.

Intro: Co-Work

How do the ways we know and with whom we know shape research practices? And what happens if we place inequalities and power relations at the center of the research process, trying to build ways of working together from there? This piece draws on the process of my PhD research about the (trans)national border space between Germany and Ghana and reflects on ways of knowing with people who experienced forced and ordered returns to Ghana.

The search for novel research practices started with moments of tension during the early stages of fieldwork in Accra and Kumasi, Ghana. In the initial meetings and conversations with people who had been returned and rendered immobile, it became clear that a critical reflection on research practices was necessary to engage ethically with embodied border experiences. Intersecting positionalities surfaced in nuanced ways. Conversations ended with a deep sigh and the question, “How can I make you understand?” At other times, people declined participation, as joining a Germany-based project was seen as supporting German border policies. This translated into refusals to participate in the project and scepticism about the possibility of creating a common base for understanding. Consequently, I asked myself how ethical forms of working together might unfold in a field shaped by exclusionary borders and violence, where my positionality as a white researcher holding a German passport was highly problematic—linked as it was to a subsequent mobility privilege and to the violence of the border regime itself. The question about a possible fieldwork, “a possible anthropology” in Anand Pandian’s (2019) words, intensified: What does anthropology offer in terms of knowing, particularly in contexts of mobility inequalities and the high danger of reproducing them? How can paying attention to moments of discomfort (Ballestero and Winthereik 2021) and to situations of being rejected in the field (Schramm 2007) be a fruitful path toward new forms of knowing together?

In one of the classical works on collaboration, Lassiter (2005) suggests thinking about collaborative research “as an approach to ethnography that deliberately and explicitly emphasizes collaboration at every point in the ethnographic process, without veiling it – from project conceptualization, to fieldwork, and, especially, through the writing process” (16). Whereas forms of working together are a basic part of ethnographic work, his approach conceptualizes a narrow meaning of collaboration as a central point of orientation in each step of the project: starting from the research design, throughout the fieldwork period, and during writing. Through the experiences in my research, I want to add a perspective to the co-production of knowledge that emphasizes a different dimension of “working together” in the sense of what I call co-work. In contrast to the narrower understanding of collaborative projects—working together toward a shared goal from the start of a co-designed project towards a common output—the practices in my research speak to a broader understanding of working together through overlapping interests, asymmetric contributions, and episodic modes of collaborating.

Co-work refers to forms of situational working together that emerged through shared engagement with artifacts, media, and stories, without presuming shared expectations, equal authority, or stable collaboration. Co-work unfolded unevenly, remained contingent, and at times receded, yet it enabled forms of improvised and creative knowing that would not have been possible otherwise. Pandian (2019) declares that a possible fieldwork in current times of unease has to embrace ambiguity, improvisation, and imagination. He argues for a rethinking of methodology in the sense of flexible, sensitive, and ethically responsive research practices inspired by multiple disciplines: filmmaking, creative writing, and philosophy. These thoughts take us to what Estalella and Criado (2023) call “creative improvisations and inventive activities” (3), understood as central aspects of anthropological work. The authors invite us to pay attention to and make explicitly visible what resonates in many research practices: diverse ways of methodological engagement, the role of different artifacts and media, entangled positionalities, differences in spatial settings, and temporal rhythms. A possible research then lies in the possibilities of co-producing co-work regarding the specific context. This means thinking of research practices not as fixed methods but as experimental spaces that are open to creative engagements from a variety of disciplines to take the affordances of different research engagements seriously. Working with my interlocutors, Prempeh, Simon, and Rose, showed that, in improvised settings of co-work, an open search for research practices brought the role of different media to the foreground. Engaging with videos, photographs, text, documents, and objects allowed my interlocutors to actively co-guide both the research questions and forms of knowing together.

Pictures, Visual Sketches, and Video Conversations

During one of my weeks in Kumasi, I met Prempeh, a professional Kente weaver, for the first time at his workplace in a rural village one hour from the city. In our first hurried meeting, he showed me his Kente work, a traditional way of weaving. Later, he started telling me his story of being in and returning from Germany while sitting in front of his rented apartment. He stayed in Germany for some years and was forcefully returned to Ghana a couple of years ago. After explaining to me how he felt when he was brought to the airplane in Northern Germany and accompanied by police officers during the flight to Kotoka Airport in Accra, he wrapped up the conversation with a deep breath and the question, “How can I make you understand?” Since there was no more time left that day, we ended up exchanging phone numbers.

Since then, we have been in frequent contact and have tried finding ways to work together. After we had known each other for some months, Prempeh started sending me pictures and short video clips related to questions we had previously discussed in WhatsApp conversations or in-person meetings. With a short text, the audio-visuals popped up on my phone, sent from Kumasi to Accra. In meetings during my stays in Kumasi, we looked at these pictures again, and he elaborated in detail as to why he had sent me the photos, what they depicted, and what they symbolized to him. Related to the topic of what made him comfortable after the return, he sent me a picture of him standing next to the Kente shop he used to own. “If everything goes gradually, if every day—day in day out—if the business moves as required, then I will be comfortable.”

Based on our earlier conversations, this dynamic of exchange through pictures and short video clips further unfolded. The audiovisual medium enhanced the way he told his story in the sense that he decided what to show me in which ways and that I was able to ask questions arising from the photographs and videos (for example, about the former shop he owned). Not only did this enrich the talks we had based on the photos at face-to-face meetings, but it also led me to get engaged in this dimension of expression. After a few months of research and the intensifying co-work, I began to produce short video clips consisting of material recorded by research partners and me. At the time, I did not plan to produce a film in a professional manner to be published as a research result. Rather, my aim was to create visual sketches through which I could work on my understanding of the experiences and, in turn, enter into a new conversation with the people I worked with. The clips, therefore, proved to be methodological tools in their own right.

The co-work with Prempeh represents an episodic practice of shared activity based on different media artifacts. It relied on his aim of telling his story to “release the stress through remembering it,” as he repeated during some sessions, and a political effort to let people know what happens during forced return. While my aim overlapped with his political stance, my commitment was further based on my academic project. Co-work consisted of a shared practice based on partial alignment of different but overlapping goals and was guided by our common interest in audio-visual formats.

In one sequence of a video clip, I retold Prempeh’s story, which he shared with me during the meetings and across locations through pictures and his self-made recordings. In another meeting, we sat in a garden space in Kumasi and watched the video clip consisting of Prempeh’s and my visual material.

While the video played on the laptop in front of us, Prempeh commented. Repeatedly, we stopped the visual narrative, and he added a note, asked questions, started narrating, or corrected some of my descriptions. Through Prempeh’s visually-supported storytelling and my narration of his story, we arrived at engaging conversations centered around retelling, accentuating, and focusing. These moments of translating his story into different represented mediums from our different standpoints of understanding were special in the sense that they did not lead to an actual repetition of a narrative; each medium and each story led us in very different directions of thinking together, from experiences in Ghana and the notion of “home” to political discussions and talks about music.

As this process changed from one meeting to the next, the importance of the medium of the talks, the ways in which experiences were nuanced in different ways through different audiovisual artifacts, became central (Pink 2007). Different modalities unfolded around self-made pictures, short conversations on messaging apps, talks about biographical photographs, and comments on video clips. As shown by Sarah Pink (2009), audio-visual material can play a significant role in understanding one’s experiences apart from a purely verbal narration by emphasizing the sensory, embodied, and material dimensions of narrative practices. Thereby, sense-making streamlines the importance of senses in epistemic processes.

In her work, Pink not only argues for the importance of the senses in ethnographic research but also invites us to indulge in experimental ways of knowledge production. She describes that “sensory ethnography […] does not privilege any one type of data or research method. Rather, it is open to multiple ways of knowing and to the exploration of and reflection on new routes to knowledge” (Pink 2009, 4). She further clarifies that sensory ethnography does not necessary replace other methods, such as participant observation and interviewing, but argues that those methods always include visual and auditory moments which should be explicitly addressed and centered in the process. In fact, she calls for a shift of attention and more emphasis on these moments in order to explicitly recognize them as parts of research practices and as epistemic door openers (Pink 2009, 7).

Prempeh’s and my work included walk-alongs, conversations, and participation. Audiovisual materials proved to be a central part of these other research practices: filming video clips during walks, conversations based on visual sketches, and audio recordings of participation in Kente weaving. These media stressed the multi-sensory ways of sharing experience-based knowledge without choosing one ultimate approach to co-production. Rather, the process of searching for ways of knowing together and alongside one another characterized our co-work.

Co-Writing

During one of our meetings in Osu in the southern part of Accra on a Wednesday afternoon in July, Simon, one of my closest interlocutors in the city, dropped a piece of paper on the table in front of me. Flashing one of his captivating grins, he said, “All the stories came back. I didn’t even know where to start or where to end. I don’t know if it makes sense.” With a sigh, he slumped into the chair opposite me. For the next two hours, we read through the text he had written, he commented, we discussed, and I filled some pages in my research diary with notes about our exchange. After our first meetings in the backyard of his compound just outside Accra and later walking together through his neighborhood, passing by the construction site where he worked, and visiting the beaches where he went to as a child to swim in the sea, he brought self-written texts to our sessions—usually based on a topic we had agreed on beforehand.

This practice came about through a conversation during one of our shared afternoons, where we eventually started drawing little sketches on a piece of paper. Holding a pen in his hand, Simon stated, “I wrote a lot when I was younger. I would like to do that again.” We then started talking about writing, a central and sometimes tedious process in my everyday life during research. The conversation led to us agreeing to share texts on previously discussed topics. While his topics spoke to themes of his biographical movement history and his border trajectory, mine captured reflections on my ongoing research and often included summaries of our meetings.

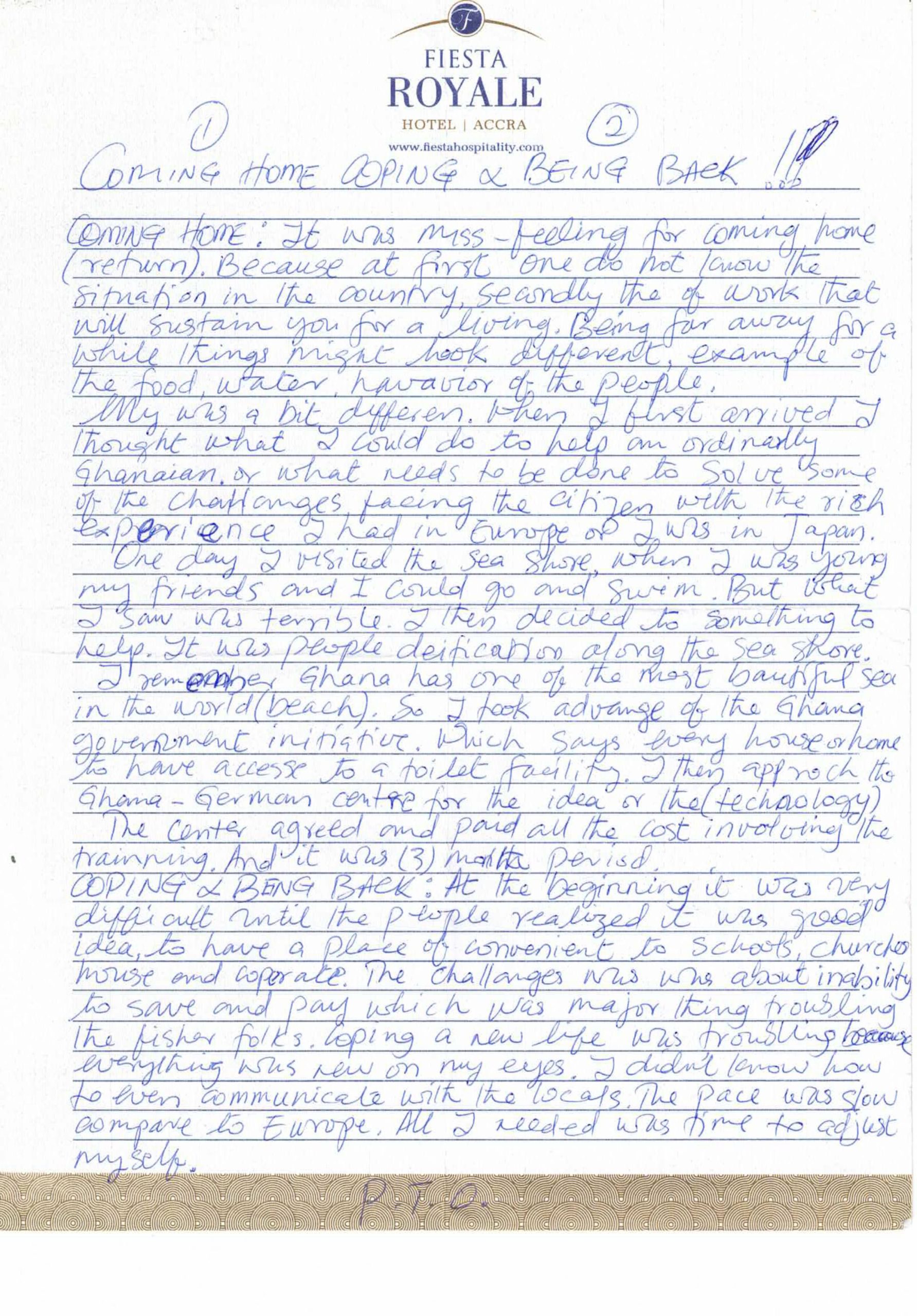

From that point on, Simon shared his stories and analysis in writing. Sometimes I read silently, then listened to his comments; at other times, he read his texts aloud and reflected on them as he went. Meanwhile, I scribbled notes into my own notebook, recording both his words and our dialogue around the text. These repeated translations on paper materialized different stories and parts of Simon’s biographical movement trajectory and border memories, combined with my reflections on our meetings and his stories. They showed that co-work not only produces shared knowledge and understanding, i.e., within the exchange between people in the sense of Ingold’s (2017) “human correspondence,” but also that affective and embodied knowledge can be co-produced through co-writing and the medium of text (Campbell and Lassiter 2014, 129–134). What made these meetings compelling was the dynamic unfolding around the artifacts: Our conversations revolved around the texts, engaged with them, resisted them, and expanded them. The direction of our exchanges was largely guided by this medium. Simon’s texts were often written late at night after his working shifts – “usually after 10 o’clock, and then came all the memories,” as he mentioned during one of our meetings. The very title of one of his pieces, “Coming home, Coping & Being Back!!!,” written in blue ballpoint pen on a notepad, already pointed to one trajectory of his story. He wrote that “it was a mixed feeling for coming home (return). Because at first one does not know the situation in the country; secondly, the kind of work that will sustain you for a living. Being far away for a while, things might look different – for example, the food, water, and behavior of the people.”

Yet the transformations that his written narration underwent in our encounters were what proved most fascinating: a condensation, a change of direction, a branching out, a new stream. The text about coming back from Germany led to the story of his first travel to Libya on a scholarship and his experience of return back then. The topic of coping drifted into a discussion on the political landscape in Ghana today and how people try to cope with the economic instabilities they face, coming back to his company’s work of building biodigesters—the business he started after he returned from Germany. Simon wrote pieces about his time in Germany, his return to Ghana, and his hopes for everyday life. The textual artifacts thus spoke to his various times on the move, some of which bore titles like “Coping” and “Japan Uncovered” while others began with openings such as “All started when…”

In classical approaches of collaborative research and co-writing, Campbell and Lassiter (2014) argue that “ethnographic writing does much more than communicate or represent; it works between people, making and remaking the individuals, communities, and issues it engages” (131). Ariel de Vidas (2020) summarizes her collaborative experiences of co-interpretation and collaborative work with texts based on the reactions of her partners: “That’s your job, not ours” (299). In her research, collaborators refused to work on her ethnographic writing as this was seen as part of her strength and work that should be acknowledged as such. Practices of co-reading, co-writing, and especially co-interpretation are thus not always wished for and have to be considered within the specific research context and its actual purpose.

The aim of jointly reflecting on stories and the mutual telling, reading, and writing in the project were not guided toward co-interpretation and the legitimization of the storytelling within my ethnographic writing. Rather, the approach to writing emerged from the encounter with Simon, who proposed to write texts about his life trajectory as a way of remembering (“all the memories came back”). Coming from there, these cycles of re-reading across the written word developed over time and constituted an epistemological practice to unravel the embodied forms of knowing inscribed in writings on biographical trajectories of (im)mobility. Unlike telling or listening to a story once, these loops added layers of complexity; they made explicitly visible that knowledge about the border manifests in multiple border crossings and is part of a broader mobility trajectory beyond the logic of return as a closed and one-dimensional phenomenon. The search for ways to know together with Simon resulted in practices of writing, reading and talking. Our co-work was mainly based on our common interest in writing, accompanied by a shared sympathy. As such, Simon described the work with texts as a valuable practice to remember his story while documenting it for other people who have to live through return.

Documents and Objects

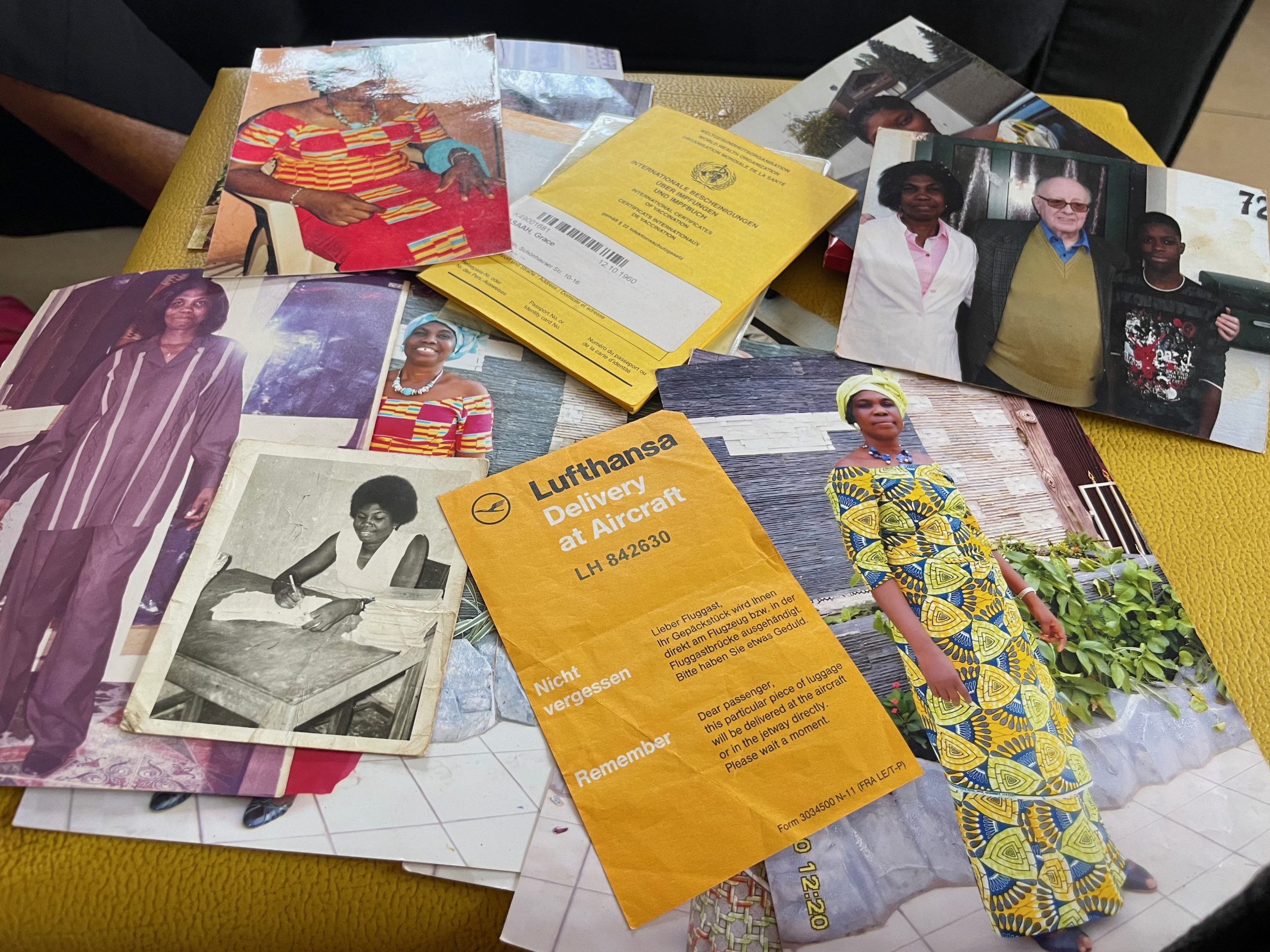

A stamped flight ticket from Hamburg to Accra, a yellow vaccination passport, dozens of photographs, and several documents covered the small stool in front of Rose and me. In one picture, Rose stood in Ghana on a Sunday in front of a church. In another, she posed in Germany next to a retired judge, the person she had worked for. Beside these images was a Covid vaccination card issued at the asylum center near Cologne. Underneath a sheet with filled lines and ticked boxes was sticking out: a formal letter and the authorization for financial support as a “returnee.” This was a usual setting of one of our Monday morning conversations in her apartment, which she shared with her two adult daughters. Often, she invited me to glance over these materials: the letter and International Organization for Migration (IOM) authorization under the program Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR), her passport, and documents stamped by German authorities. Rose kept the documents and photographs in a specific album, some photos neatly arranged, others peeking out loosely from the book.

Her story unfolded across these documents, certificates, photographs, and official papers. From a black and white photograph in which she sat on a table correcting her pupils’ homework—her first job in Northern Ghana— to photos from the years she spent in Nigeria selling food at the school yard where her husband was employed as a teacher. Later, during the 1980s, she experienced forced return to Ghana and noticed her growing desire for financial independence from her husband. After her husband died, she started selling food on the streets and worked in a clothing shop. One picture showed Rose posing in an outfit for a photograph that the show owner used to promote his designs.

After some years, she got the opportunity to travel to Germany through her family’s connections. Her time in Germany encompassed care work for the retired judge she was invited by. In one of the photographs, she stands next to him in her white pantsuit, which she wore for her daily work: “Taking walks, cooking, bathing. That was it,” she told me while we glanced over the pictures. After some years of moving between accommodations, she decided to seek asylum and stayed in an asylum center where she received the Covid certificate and the vaccination pass. Later, she returned to Ghana; the flight ticket marked the date of departure. During our conversation, second-hand bags hanging on curtain rails recalled her life in Germany, linking it to her present work in Ghana; Rose bought them in regular flea market visits in Germany and now sells the bags at Makola Market in central Accra. Embodied in the documents, photographs, and objects, Rose narrated her biographical (im)mobility story. The co-work with Rose consisted of these Monday morning talks in her apartment, cooking sessions, and visits to Makola Market. It was based on a shared sympathy and a gender-based solidarity. Our exchange on gendered violence and a shared standpoint regarding gendered inequalities formed the baseline of our conversations.

Within the research process, engaging with documents and objects became a central methodological orientation. Rose engaged with these materials as key artifacts that both expressed and embodied experiences (Riles 2006) while evoking emotions (Navaro-Yashin 2009). For instance, Pérez Murcia and Boccagni (2022) ask, “Do objects (re) produce home among international migrants?” Thereby, they address four dimensions of objects: They embody collective belonging, are a way of feeling at home, carry memories, and form a web of relations between scenes and settings linked to what people understand as “home.” As central engagements in the project, Rose actively chose documents, biographic photographs, and objects and brought them into conversation to relate to her knowledge of borders. This perspective made visible how border knowledge manifested in memories of moving from one camp to the next, in the collection of documents, and in second-hand bags on curtain rails. They offered a lens through which we could explore different episodes of her journey, bridging memory, materiality, and narrative in our conversations.

Reproducing Inequalities?

Forms of co-producing knowledge in ethnographic work are manifold, developing out of the respective context and involving different modalities, practices, and ways of expression. In my project, co-work describes a process of searching in which interlocutors and I engaged in shared activity without necessarily working toward identical analytical, political, or representational ends. It was based on aims of mental stress relief through remembering, interests in working with a given medium, mutual sympathy, an academic project, and an overarching political commitment to make inequalities and violence visible. Improvisation and a creative openness were the foundation of finding shared practices to address these overlapping goals.

However, this attempt at doing research is not free from the risk of reproducing power relations, interdependencies, asymmetries, and hierarchies. Quite the opposite! I learned that co-work does not happen automatically—it must be constantly negotiated. We began the work with different expectations, experiences, and positionalities, which shaped how we related to one another and how power and inequalities played out in the process: Who gets to speak? Who decides what counts as relevant knowledge? What do we even want to know and want to let the other person know? How do we structure the steps in the co-work? Which research practices do we actually want to engage with? In that sense, finding shared interests and practices compatible with everyday routines and other obligations was far from easy. It took time to figure out: What are we working toward together? What is our interest in the co-work? What output do we envision?

In the various forms of co-work in my project, the response to these questions emerged above all through a shared search for practices that enabled diverse forms of working and knowing together. Although not guided by identical interests, goals, or possibilities, a space took shape for episodic and fragmented knowledge co-production, which was also repeatedly characterized by a mere coexistence alongside one another, such as writing a story alone and sharing it later or taking photographs while the other person creates a visual sketch. From my experience, I would describe this more detached form of shared knowing as a possibility in which researchers and interlocutors can formulate their own ideas and goals and contribute them to the process without attempting to transform them into a collective whole. However, this leads to the question of authorship. If the knowledge and the research practices are co-produced, how can that be made textually visible when a dissertation must be single-authored? And what alternative outputs might be realistic? An exhibition after the dissertation, a book, or a film project? Navigating the questions around ownership and recognition was challenging and ultimately led to the conception and implementation of a dedicated film project to respond to shared expectations of making the co-produced knowledge public beyond the academic sphere.

Further, the process raised broader questions about what kinds of co-work are possible within the constraints of an individual PhD research project with its tight temporal, financial, and organizational framework. Relatedly, once the PhD project ends, what happens next? How can the co-work have a longer-term influence for all involved rather than a short-term relevance? At the time of writing this piece, the film project is ongoing with the hope of a follow-up project.

Thus, while co-work holds great experimental potential, it is far from straightforward. I want to suggest some orientations that helped us navigate these challenges, particularly where, as in the project, power, authority, and access to resources were fundamentally unequal. In my case, transparency about expectations from the outset and throughout the process was crucial. This included intentions, limits, and even institutional pressures. A central guideline was to recognize how power, privilege, and authority shape who is heard, who leads, and whose knowledge is valued in what contexts and by whom. Conversations about asymmetries with interlocutors were important steps toward taking responsibility as a way of being responsive regarding my own expectations and the authority I held within the process.

However, I also learned that not all disagreements are meant to be resolved. Enduring differences and inequalities were part of the research process as was honoring refusals. Sometimes, silence, rejection, or mistrust was a form of care or protection for one’s boundaries—whether in relation to one’s commitment or in response to past violent experiences and the risk of retraumatization. Enduring these moments required resisting the urge to smooth over discomfort quickly. It entailed a commitment of “staying with the trouble” (Haraway 2016) and also letting co-work engagements fade out if they did not align, as happened with some former interlocutors during fieldwork. Thereby, one of the most essential aspects was taking time. Building the trust to discuss expectations, interests, and needs required repeated engagement, consistent follow-through, and staying present even when conversations were demanding.

Summary

Anna Tsing (2005) writes that collaborations are forms of friction arising from differences, “the productive rubbing together of varied historical trajectories or modes of practice. Productive here means producing something new, whether positive or negative. It is not a praise; friction is useful to consider great crimes as well as unexpected escapes” (xi). From working with Prempeh, Simon, and Rose, one main lesson was that tensions, asymmetries, hierarchies, and power imbalances are intrinsic to and most visible in processes of co-producing knowledge. Yet, co-work—understood in terms of an episodic, fragmented, and experimental working together and sometimes working alongside—invites us to take people’s interests, expectations, ways of expression, aims, and levels of commitment seriously. The ethnographic encounter signifies here an improvised and multimodal space for various ways of co-producing knowledge that is characterized by a processual search for research practices, including conflicts and unexpected outcomes.

Bibliography

Ariel de Vidas, Anath. 2020. “Collaborative Anthropology, Work, and Textual Reception in a Mexican Nahua Village. American Ethnologist 47 (3): 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12913.

Ballestero, Andrea, and Brit Ross Winthereik. 2021. Experimenting with Ethnography: A Companion to Analysis. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478013211.

Campbell, Elizabeth, and Luke Eric Lassiter. 2014. Doing Ethnography Today: Theories, Methods, Exercises. Wiley-Blackwell.

Estalella, Adolfo, and Tomás Sánchez Criado. 2023. “Introduction: The Ethnographic Invention.” In An Ethnographic Inventory: Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry, edited by Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella. Routledge.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11cw25q.

Ingold, Tim. 2017. “On Human Correspondence.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23 (1): 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12541.

Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo3632872.html.

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2009. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15 (1): 1–18.

Pandian, Anand. 2019. A Possible Anthropology: Methods for Uneasy Times. Duke University Press.

Pérez Murcia, Luis, and Paolo Boccagni. 2022. Do Objects (Re)Produce Home Among International Migrants? Unveiling the Social Functions of Domestic Possessions in Peruvian and Ecuadorian Migration. Journal of Intercultural Studies 43 (5): 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2022.2063825.

Pink, Sarah. 2007. Doing Visual Ethnography. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857025029.

Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249383.

Riles, Annelise. 2006. Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge. University of Michigan Press.

Schramm, Katharina. 2007. “‘You Have Your Own History. Keep Your Hands off Ours!’ On Being Rejected in the Field.” Social Anthropology 13 (2): 171–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2005.tb00005.x.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton University Press.

Melina Götze is an academic staff member and PhD candidate at the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology at Goethe University Frankfurt. In her PhD research project, she focuses on the (trans)national border space between Germany and Ghana, especially in terms of forced and ordered returns. Thereby, she asks how the category of the “returnee” comes into being and is questioned by people who have lived through return. Melina is particularly interested in questions around knowledge co-production and in experimental methodological approaches to social inequalities and political subjectivities. Additionally, she is part of the research group Anthropology of Global Inequalities and active in anti-deportation and mobility rights initiatives.