Representations of Political Violence in Museological Spaces

Decolonial Strategies, Contested Memory and Transformative Potential

Museums have traditionally served as custodians of historical artefacts and of normative narratives, playing a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the past, of the political violence that shaped the emergence of present-time social orders, and of the lasting implications for the present. However, the process of disseminating such images and narratives through museums is far from objective or neutral. The process of selecting which aspects of history, whose stories, or which ‘imagined communities’ are emphasized while others remain invisible is inherently political and subject to the influence of power dynamics. As a result, museums contribute to the highly contested practice of demarcating what constitutes legitimate versus illegitimate violence, or else what counts as violence at all. At the DGSKA 2023 conference, the workshop “Representations of Political Violence in Museological Spaces” brings together nine researchers to shed light on exactly this topic, through empirical, theoretical, and curatorial perspectives.

The Power of Museological Representation under Challenge

Central to the demarcation mentioned is the choice of terminology used to label acts of violence as political or criminal: whether violent action is represented as an example of “terrorism,” “liberation struggles,” “defense,” or “insurgency” makes a difference in normative classification. These labels are not merely descriptive but carry significant political weight, determining which actors are thought to be legitimized to use violence to achieve their goals and under what circumstances, and which not. Museums, through their selective highlighting of specific forms, moments, and motifs of violent action, actively participate in shaping public perceptions and understandings of political violence.

Post- and decolonial perspectives have exposed the underlying power dynamics and legitimizing functions of many established and hegemonic narratives as well as images within museum spaces, highlighting their contentiousness. These narratives often reflect colonial biases and euphemistic representations of conquest and subjugation, perpetuating a skewed historical perspective that is part of legitimizing and power-maintaining structures. Consequently, debates and procedures have emerged regarding the repatriation of artefacts and human remains obtained through coercion and violence, especially in view of those originating from former colonial territories. These discussions challenge the justifications and concepts associated with colonial collections and provoke a critical reassessment of how conquest, dispossession and subjugation have been portrayed, as well as the role anthropology as a discipline has played in exploiting exactly these territories and subjugating their peoples.

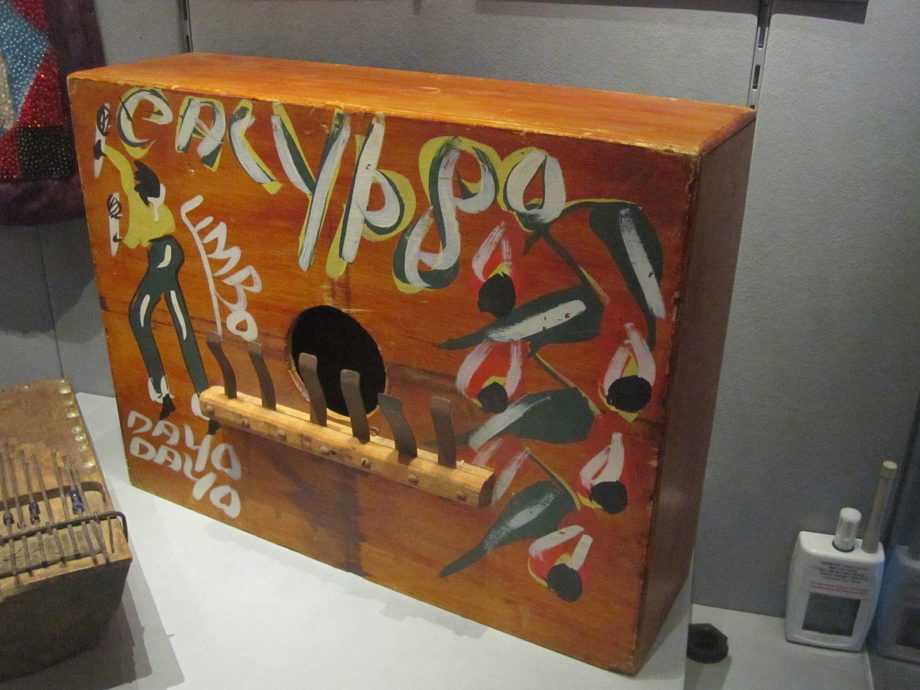

Rumba box on exhibit at the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool, England. © Wikimedia User Rept0n1x

Moreover, museums are increasingly engaged in the reappraisal of their representations of, e.g. civil wars, national histories of domination, and the human rights violations that went along with or were strategically applied in colonization processes. By adopting decolonial strategies, museums strive to address the imbalances and injustices inherent in historical narratives and selective representations. This oftentimes involves acknowledging and amplifying the perspectives and experiences of communities and individuals whose voices have been historically marginalized or silenced. By incorporating diverse viewpoints and narratives, museums can indeed create space for alternative interpretations that challenge dominant power structures, shed light on the complexities surrounding political violence, help understand historical paths which led to present-day social and political ligatures, or facilitate processes of ‘unlearning’ conventional readings of the past and its impact on the present.

One example for the latter approach is the collaborative project “c̓əsnaʔəm, the City before the City” which is on display at the Museum of Vancouver. The exhibition raises the question whose home Vancouver is by reexamining excavated findings such as shells, worked bones and other cultural artefacts, and by explaining their meaning in political, economic, and ceremonial activities of the local Musqueam people. With “c̓əsnaʔəm, the City before the City”, the Museum of Vancouver aims to generate public awareness of Indigenous history and stimulate conversations about past and current relationships between Indigenous and settler societies in the city and beyond. In the words of Musqueam cultural advisor Larry Grant, the exhibition “aims at ‘righting history’ by creating a space for Musqueam to share their knowledge, culture and history and to highlight the community’s role in shaping the City of Vancouver.”

A further example of an exhibition that offers a decolonial perspective, this time through an artistic lens, is “Art from Guantánamo Bay”. It was shown in 2017/2018 at the President’s Gallery, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York, curated by Erin Thompson, Paige Laino, and Charles Shields. Detainees created artistic work following their arrival at the United States military prison camp known as Guantánamo Bay, but only a fraction of the works were cleared to be sent out to the lawyers and families of the six artists. The exhibition showed nearly a hundred of these evocative works and created a public discourse beyond the dominating narrative on Guantanamo Bay. Following the exhibition, under the presidency of Donald J. Trump, a ban on the release of artwork made by detainees at Guantánamo Bay was introduced that made it impossible for newly created works to travel beyond the walls of the detention site. Under a new policy that came into effect in 2023, detainees are allowed to take “a practicable quantity of their art” when they leave Guantánamo. The vague phrasing has not been defined further.

Contemporary Violence in Museum Spaces

In addition to museum practices which serve the function of scrutinizing or “righting” established interpretations of the past, representations of contemporary political violence are also emerging within museum contexts. This includes the presentation of today’s violent actors, which – in itself – implies a set of challenges for museums. Willingly or unwillingly, by drawing on and portraying ongoing conflicts, they navigate the complexities and grey zones of these conflicts and position themselves in the related political conflict dynamics.

One example of an exhibition addressing imagery of political violence on a broader scale is “Mindbombs – Visual Cultures of political violence” that was shown at Kunsthalle Mannheim in 2021/22 and curated by Sebastian Baden and Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann. The exhibition opened up a highly topical artistic perspective on the history and political iconography of violence showing partly explicit scenes but mostly artistic appropriations relating to them. It included works reaching back more than 200 years ago to the French Revolution, works relating to contemporary right wing terrorism such as the NSU complex in Germany, and recent acts of political violence by the so-called Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. From among the images, the most explicit propagandistic ones were those lent to the museum by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. These are images from the French Revolution that show people being executed, including the French king, Louis XVI. However, the majority of the visual material displayed was artistically filtered through practices of appropriation.

Mindbombs exhibition in Mannheim, exhibition view with works of Édouard Manet, Francis Alÿs and Natalia Schmidt. © Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann

In their relation to contemporary political violence, museums may also choose not to display explicit imagery for several reasons. Firstly, it is essential to consider the sensitivity and potential trauma such imagery can evoke in viewers, prioritizing their emotional well-being. Secondly, ethical concerns surrounding consent, dignity, and potential exploitation of the victims and survivors arise, demanding responsible and respectful representation. Thirdly, museums may aim for inclusivity, taking into account diverse audiences with varying sensitivities, ensuring accessibility for all, including children. Additionally, the limitations of explicit imagery in conveying nuanced understanding, or the restrictions of legal regulations, may further discourage its display. Museums can also explore alternative methods to foster engagement and promote deeper comprehension of political violence while maintaining sensitivity and respecting the diverse needs of their visitors. While the latter concern might be widespread in Germany, an example from Iraqi Kurdistan shows how explicit imagery can become the focus of museological displays: The “Museum for War Crimes” in Sulaymaniyah and the memorial in Halabja both address the history of the Kurdish genocide displaying graphic images of poison gas victims and executions. The geographical proximity between the space where the events have taken place and the space where the imagery is displayed can serve as one point of departure for an explanation of the decision to not censor such explicit content. The desensitization of the population based on their collective experience might be another one. Although re-traumatization might occur, the interest in seeing the massacre documented in an institution that serves as a public memory space evidently weighs more heavily.

That said, museums’ practices require careful consideration and engagement with the ethics of representation depending on the respective context, as they shape public perceptions and viewing conventions and thereby undoubtedly render an influence on political discourse. In concrete terms, any decision about displaying explicit imagery of political violence affects the distance between the viewers and what they gaze at, and may thus even contribute to reifying victims when allowing us to “regard the pain of others” – in spite of possible noble moral aims to foster empathy through confrontation.

The Transformative Potential of Museums’ Practices

It is crucial to critically examine the forms and bodies of knowledge employed in museum contexts to display or commemorate political violence but also to recognize their transformative potential for the social processing of experiences of violence. The mentioned “Museum for War Crimes” in Sulaymaniyah and the memorial exhibition in Halabja are cases in point: the ways in which memories of violent experiences are represented in spaces open to the wider public influence the shaping of collective identities. In a similar vein, the South African Apartheid Museum tells the history of the country’s brutal segregation policy, but it also informs about the political action that helped Black consciousness rise and eventually led to a new political order.

The entrance to the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Your purchased ticket indicates what “color” you are, therefore which entrance your ticket is valid for. © Annette Kurylo.

A central aim of the permanent exhibition in Johannesburg is to keep alive memories of the high price of violent suppression and to promote a sense of identity with the post-Apartheid democracy. This museum is therefore also meant to function as an agent in building peace and community in a nation divided by past violence, lasting inequalities, and differing memories of the troubled relationships. In the case of South Africa, where reconciliation has been a guiding concept for the political and societal transition process, measures were taken to address crimes, human rights violations, second class treatment and the resulting deficits in societal trust (transitional justice), as well as to preserve and educate the narratives of what occurred (memory discourse and education). Museums like the South African Apartheid Museum, the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, which commemorates the role of students in fighting the Apartheid regime, or the Capetown based District Six Museum, share the mission of building a community where human dignity, diversity and peaceful coexistence are respected.

There, as well as in other cases like Cambodia, Chile, or Paraguay, museums offer solutions to the problem of how the legacy of mass violence could be tackled and transformed, such as by amplifying the victims’ voices, articulating their perspectives, needs and demands. But these are not uncontested.

Genocide-Museum Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. © Gerd Eichmann

When Germany offered financial aid to Peru in the early 2000s for the erection of a museum to commemorate the victims of the civil war from the 1980s and 1990s, and to host the archive of the Truth Commission, the Peruvian government rejected the offer, arguing that other investments were more pertinent. In 2015 a museum of the civil war was opened in Lima, but following a different concept: the “Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión Social LUM“ aims to not ‘take sides‘ with specific victims but rather to represent the multi-perspective history – and society, as Fabiola Arellano Cruz points out in her comparison of Chile and Peru.

It is exactly because narratives across society and the political spectrum tend to diverge drastically after violent conflicts that museums have the potential to be forums in which such divides can be made visible, multiple viewpoints may be experimented with, and worked on. After all the fact that there is memory contestation represents the inherent diversity and conflicting interpretations of historical events within a society. In the context of museological exhibitions on recent political violence, memory becomes a contested terrain where various groups assert their own narratives and perspectives. It is the responsibility of such exhibitions to navigate this complexity while also acknowledging the power dynamics that shape the construction of memory. By doing so, they can challenge dominant narratives and promote a more inclusive understanding of the represented events. Yet they may also contribute to escalating situations and further controversies, making hitherto implicit positions visible and help political clarification by triggering debates. The exhibition on “Vernichtungskrieg: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht, 1941-1944” (War of Annihilation: Crimes of the Wehrmacht), curated by Hannes Heer for the Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung can serve as an example. The exhibition traveled through Germany and Austria in the second half of the 1990s and provoked polarized reactions, including public demonstrations for as well as against the exhibition, and broad media coverage. The fact that some factual mistakes were discovered in the first version of the exhibition meant water on the mills of some revisionist groups who rejected the whole idea of a criminal German Wehrmacht, but at the same time the dispute stimulated even more critical research on historical detail and related questions of complicity and entanglement. It eventually led to a revised exhibition made public in 2001 and altogether facilitated a critical reexamination of public and private memories of the wartime past in Germany, uncovering and falsifying popular myths about the supposedly “clean Wehrmacht”.

Limitations and Outreach Strategies beyond Exhibiting

It is important to recognize the complexities surrounding contested memory, transformative potential, and audience accessibility in museological exhibitions on political violence. By acknowledging and navigating contested narratives, foregrounding hitherto marginalized voices, and incorporating interactive elements that foster community engagement, topical exhibitions can broaden their transformative impact, challenge hegemonic interpretations, and contribute to lasting social change and deeper understanding of the complexity of the very entanglements. The transformative potential of museological exhibitions lies exactly in their ability to challenge prevailing narratives, promote dialogue, and facilitate healing and eventual reconciliation processes. By foregrounding subaltern or marginalized voices and perspectives, exhibitions have the capacity to generate empathy among visitors and foster different readings of political violence. Through spaces for reflection, education, and debate, they contribute to the potential for discursive and social change. However, critics argue that the transformative potential of museological exhibitions is limited due to their tendency to attract only audiences already predisposed to engage with the topic. This argument highlights the importance of broadening the reach of these exhibitions to encompass a more diverse and extensive audience. To achieve this, it is essential to address structural inequalities beyond the confines of the museum walls.

Montréal, 11 July 2016: Nadine Jean in the role of Marie-Josèphe Angélique, a female slave who was executed for arson in New France in 1734. © Coastal Elite

One effective approach to expand the access to a broader audience is to incorporate interactive elements, such as community dialogues and workshops, within the scope of an exhibition. By actively involving visitors in discussions centered around themes of social justice and truth-finding, exhibitions hold the potential to empower individuals to become agents of change within their communities. This approach not only ensures broader audience engagement but also encourages the dissemination of ideas and perspectives beyond the confines of the museum space. However, as several of the quoted examples demonstrate, the fruits of such labor may be harvested only after generations.

Introducing the related DGSKA Conference Workshop

As laid out above, museums have a profound influence on shaping normative narratives and images of political violence and on the social identifications which they offer. By selectively highlighting certain aspects while neglecting others, museums participate in the demarcation of legitimate versus illegitimate violence, affecting public perceptions and interpretations. Especially critical feminist and postcolonial perspectives have challenged established narratives and exposed power imbalances within museum spaces. The ongoing decolonization of collections and exhibitions seeks to address these imbalances and creates opportunities for diverse, inclusive, and transformative representations of historical and contemporary political violence. Through critical examination and engagement, museums have the potential to contribute to the social processing of experiences of violence and foster a more nuanced understanding of its complexities and consequences; yet conditions apply: questions arise regarding the interpretations of violence suggested to museum audiences, the actors involved in determining those interpretations, and the intentions behind them. Furthermore, understanding the utilization of decolonial strategies and forms of co-production is vital in evaluating the effectiveness and inclusivity of museological representations. Empirical, theoretical, and curatorial contributions all open up opportunities to explore these complex dynamics and shed light on the implications and effects of chosen representations of political violence. In our workshop at this year’s DGSKA conference, the invited scholars further explore the intricate relationship between art, politics, memory, and societal discourse within different contexts.

Zoë De Luca’s examination of writing theft on a continental scale raises questions about cultural appropriation and power dynamics. Birgit Bräuchler and Alexander Supartono critically analyze the political decontextualisation of art in Documenta 15, shedding light on the tensions between recolonization and decolonization in the art world. Anika Oettler challenges linear narratives in Colombian museums, offering alternative perspectives on objects. Sabine Mannitz and Rita Theresa Kopp delve into Canadian museums, unravelling colonial violence and exposing hidden histories, using, among other things, the example of the Museum of Vancouver’s exhibition “c̓əsnaʔəm, the City before the City”. Kaya de Wolff reflects on memories of political violence evoked in the Memorial da Resistência in São Paulo, Brazil. Sebastian Köthe presents the complexities of exhibiting art from Guantánamo, raising ethical and political questions. Finally, Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann discusses Amna Elhassan’s temporary memorial titled “Deconstructed Bodies: In Search of Home” at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, which commemorates the victims of the 2019 Khartoum Massacre. Together, these thought-provoking studies provide valuable insights into the intricate connections between art, politics, memory, and the construction of collective narratives.

As a researcher and curator, Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann is interested in theoretical and artistic engagements with political violence from a mostly decolonial perspective. She critically questions the production and transfer of knowledge and incorporates digital research tools to conduct and present her research. She has just finished her dissertation, in which she uses curatorial practices as part of her digital media ethnography. Relevant publications include: (edited with Sebastian Baden / Johann Holten), 2021, Mindbombs. Visual cultures of political violence, Berlin/Bielefeld: Kerber.

Sabine Mannitz works at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) as a Head of Department and Member of the Executive Board. She held researcher positions at the European University Viadrina and the University of Essex, UK, and does qualitative social research on conflicts in the course of globalization processes, contested meanings of ‘human security’, conflicts arising from collective identification, and cultures of remembrance in dealing with political violence. Her current research is examining political strategies which aim at redressing violence of and in settler colonial states; see, e.g. (with Rita Theresa Kopp), 2022, Approaches to Decolonizing Settler Colonialism: Examples from Canada, PRIF WP 58/2022, DOI: 10.48809/PRIFWP58; or the Blog post “A Step Towards Justice: Canada Agrees to Compensate First Nations for Loss of Culture and Language.”