Felt Expertise

Analysing the Entanglement of Emotion and Knowledge in Spain’s Domestic Care Work

Upon her arrival in Madrid, Anita felt free. Having grown up in rural Ecuador as the youngest of seven siblings, her life so far had been shaped by familial duties and economic instability. Once she entered Spain, however, everything changed. In a small park situated atop the Calle de Marcelo Usera, Anita described these initial moments in Spain to me. Age 22 at the time, accompanied by a friend, and devoid of any occupational or familial connections in the country, Anita’s sudden independence propelled her into a whirlwind journey in the bustling Spanish capital.

“We arrived at a hostel in Sol, we got there but it was cold and we only had three days of lodging. (..) I arrived with a friend, we didn’t even know where we were. We came for the adventure and then what an adventure it was! Because on the third day the hostel threw us out (..), I say and now, where are we going? What do we do? Well, at least we are free.” (Interview 11 – Anita – 23.05.22[1]).

Anita endured this constant state of uncertainty for two months until she secured her first employment opportunity as an interna: a privately contracted live-in domestic care worker. She remained enthusiastic about the prospect of living with and working for a Spanish family, even though there was a flaw that was hard to ignore: the lack of pay. Astonishingly, her employers decided to not financially compensate her for her work during the initial six months of her employment, justifying their position on the premise that provisions for accommodation, sustenance, and assistance in procuring legal residency were sufficient. Although I was taken aback when Anita told me about this, she said she displayed an unwavering strength in the face of this adversity. According to her, she has a lot of power and strength due to her daughter being dependent on her, whom she gave birth to in Madrid and whom she is raising as a single mother. Her daughter only saw Ecuador once, when Anita and her flew back to resettle – but quickly decided to return after a few months because of the lack of job opportunities. Nowadays, Anita’s daughter visits high school while her mother is once again looking for work in Spain’s capital (Interview 11 – Anita – 23.05.22).

Anita is not the only care worker who harnesses power, strength and resilience to navigate challenges, particularly for and with loved ones. It is noteworthy that such connections extend beyond biological kin. Based on my extensive fieldwork comprising six months of local observation and 50 in-depth interviews with South American care workers in Madrid, I noticed that power was construed in terms of affective affiliations and the innate ability, as well as learnt expertise, to care – even amid exploitative labour conditions. I argue that it is worth taking Anita’s comments and the many similar statements I’ve heard from other care workers at face value because only then we acknowledge and respect the subjective experience of thousands of women. In this post, I will share the first results of my research, in order to analyse the entanglements of knowledge and feeling in domestic care work. Using Catherine Whittaker’s expansion of Dian Million’s concept of “felt theory” (Whittaker 2020, Million 2009), I argue that Andean care workers in Spain feel power(ful) through a complex intertwinement of embodied, discursive and ever-changing areas of affective expertise.

Migrant care work during COVID-19

62.5 % of the estimated 477.900 domestic workers in Spain are female migrants. As such, domestic service is their most common source of employment. Besides Morocco (21.8%), most domestic workers migrated from Latin American countries, such as Bolivia (14.5%), Ecuador (9.5%) and Peru (6.5%) (Informe Estadístico de Extranjería 2022). However, those figures should be viewed with caution, as they could double if the considerable number of unreported cases of people without work and residence permits is included (Léon 2010:414). Embedded in historical colonial webs of discrimination and stereotypes, racial discrimination is one of the largest problems in Spain’s care sector (Rubio 2003). Thus, some of my informants linked their care work to slave labour.

Though domestic labour is typically coded as the domain of the feminine, given the racial imbalances at play in who carries out domestic labour in Spain, it is by no means possible to speak of a universal feminine experience, which is why Evelyn Nakano Glenn wrote about the “racial division of reproductive labour” as early as 1992 (Glenn 1992). As has been well documented (Sahraoui 2019), there is an “immense gap between the extent of discrimination (…) and actual legal cases” in Spain’s domestic care sector (Sahraoui 2019:49). Legality and discrimination were also key issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

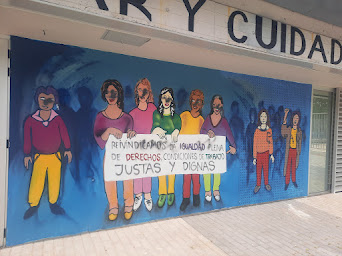

Painted over mural at the entrance of SEDOAC, an association which aims to help South- and Central-American domestic workers in Spain. Friederike Hesselmann.

Spain’s lockdown measures were strict and permitted individuals to leave their homes solely for essential activities, such as procuring food or medication, going to work (if remote work was not feasible), or caring for dependents. It is important to note that “going to work” was not a possibility for many migrants who had not yet procured legal status in Spain. Shirley, a 34-year-old Bolivian former nurse from La Paz and one of the care workers that I spoke to the most, explained how this issue affected her: “I worked as an interna. So I couldn’t go out. Yes, really.” (Interview 4 – Shirley – 18.04.22). Shirley explained her lack of freedom with the presence of police officers, who were “always on the street”. At this time, she did not have legal documentation. Subsequently, she stayed inside with her employer, who was an elderly lady with severe Alzheimer’s. Acknowledging the stress this situation caused, Shirley described how her employer became violent with her multiple times: “Sometimes I put up with too much because if I quit this job, maybe I can’t get another.” (Interview 4 – Shirley – 18.04.22)

Police parked in Usera, Madrid. Friederike Hesselmann.

Shirley’s experience was not unique. Many migrant domestic workers endured mobility restrictions, unpaid labour, intimidation, dismissal, and physical and emotional strain (Bofill-Poch/Gil 2021). Many of my informants recounted stories in which they inevitably lost their job due to the pandemic. Concurrently, the European Court of Justice denounced Spain’s failure to comply with current EU law by excluding care workers from unemployment benefits (Migration CIDOB European Union 2022). Thus, the pandemic has exposed the precariousness of the work of care workers, who were also neither entitled to minimum wage nor to written contracts. As a result, in 2022 and during my research, the Spanish government finally approved for increased protections and recognition of domestic workers, including the ratification of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention and the inclusion of domestic work under Spain’s labour law. Still, these new changes only apply to care workers, who have legal documentation and residence permits. For over half of my informants, this was and still is not the case.

Despite these challenges, many of my informants highlighted their own agency and own sense of responsibility during the pandemic. For example, Adriana, a 25-year-old woman who grew up in Colombia and Ecuador, underscored the responsibility that comes with her job and emphasised her honesty and dignity despite her lack of official documents. She told me that caring is a job that comes with a lot of responsibility. Referring to her lack of legal documentation in Spain, she maintained that she was a responsible and honest person: “And I always hold my head up high.” (Interview 5 – Adriana – 18.04.22). Interestingly, Adriana repeated multiple times that she enjoyed her work. Citing her knowledge and innate ability to care for others, which she attributed to her upbringing in her home country, she concluded: “I am a caregiver” (Interview 5 – Adriana – 18.04.22). Despite the prevalence of discriminatory and exploitative working conditions in the domestic care sector during the pandemic, many of my research participants derived a sense of pride from their work by recognizing and valuing their unique subjectivities and caring capabilities. This phenomenon illustrates a connection between subjective feelings and knowledge acquisition.

Felt expertise

Dian Million’s theory of “felt knowledge” (2009:73) posits that emotional knowledge is just as relevant as seemingly objective knowledge, which often aims for an unattainable lack of emotion. Million argues that emotions are often viewed as subjective pollution of objective purity, leading to their exclusion from discussions of knowledge production.

“The stories, unlike data, contain the affective legacy of our experiences. They are a felt knowledge that accumulates and becomes a force that empowers stories that are otherwise separate to become a focus, a potential for movement.” (Million 2014:32)

By analyzing the statements of domestic workers like Adriana through Million’s framework, it becomes clear that emotions play a crucial role in understanding their subjective expertise as caregivers.

As Adriana stated, her knowledge comes from her “gift of treating people well” and her “sense of responsibility.” These affective qualities are vital in domestic work and are often described as a form of “emotional labour” (Hochschild 2012, 2003). Hochschild’s concept of emotional labour is built upon Marx and Engels’ configuration of alienation, which posits that commodification (in the case of emotional labour, the commodification of care and emotion) alienates the product from its producer (Marx/Engels 1968:52). However, from an emic perspective, it is essential to acknowledge that migrant care workers do not necessarily share this view. Rather, they assert themselves as active agents, using their knowledge from their home countries, families, and previous job experiences to meet their own expectations of responsibility: “I have that gift of treating people well. It’s from my home country. I am a caregiver.” (Interview 5 – Adriana – 18.04.22). Thus, the commodity of care is still very much intertwined with the inherent knowledge of its producer and not alienated[2]. Instead, this knowledge in how to correctly care for others can be described as a form of felt expertise. This concept builds upon Million’s notion of “felt knowledge” and extends it to the labour market, where knowledge functions as a valuable commodity and feeling is power.

Felt power

According to Catherine Whittaker, the concept of “felt power” differs from comprehensive conceptualizations of power put forth by scholars such as Gramsci (1971), Bourdieu (1991), Wallace (1990), and Foucault (1980). Instead of pursuing a rigid and objective analysis of power distribution in social, economic, or political contexts, felt power is more intimate. Whittaker draws upon her research in the Central Mexican Highlands, where she observed that many women perceived themselves as strong and powerful when working for the collective good. Their felt power manifested through embodied, ritualistic behaviors, and was continuously reinforced through discourse. Consequently, Whittaker argues that felt power is a complex and dynamic phenomenon, deeply embedded in subjective experience (Whittaker 2020:292).

In Spain’s domestic care sector, power is difficult to grasp. Considering the precarious nature of private care work and the lack of social and economic protection for migrants with no legal permit, it might seem plausible to assert that migrant care workers lack power. However, adopting an anthropological perspective, power is not something individuals have, but rather something they do (Latour 1986). Based on my own data, I argue that care workers in Spain employ their embodied and felt expertise to experience a sense of power.

An illustrative account shared by Melany, a 24-year-old Ecuadorian woman working in the sector, resonated with me, reminding me of Shirley’s experience during the pandemic. Melany’s employer also suffered from dementia and therefore had issues identifying who was working for or working against him. During one incident, he (wrongfully, according to Melany) accused her of theft, an accusation that immediately jeopardized her employment. Recognizing her ability and knowledge in observing and understanding individuals in her care, Melany realized that changing her appearance could help her evade unemployment. Cunningly, she swapped her red T-shirt for a black one. Consequently, her employer reprimanded the “other girl” wearing the red shirt, unaware that it was Melany all along.

Melany’s account reveals the ordeal she endured due to accusations by a care recipient with severe dementia, which she remedied by assuming a different identity. Through her observational tactics and her ability to anticipate people’s preferences and aversions, she managed to experience a subjective sense of power in a situation where objective power was lacking. Additionally, this case showcases how even the racial, gendered and economic power imbalances between employer and employee are not as fixed as they might appear (to be), since there is an inherent power relation between an able-bodied caretaker and a disabled elderly person. Melany also acknowledged the fundamental role of movement in her work, particularly in terms of understanding “how to interact, how to express things bodily and vocally” (Melany – Interview 27 – 23.10.22). Therefore, her felt and embodied expertise in care and observation are pivotal to her sense of power.

Power can also manifest through the emotional depth of relationships between caretakers and the individuals under their care. Although this depth of connection was clearly lacking in Melany’s employment, many other participants emphasized the importance of their presence in Spanish families’ lives. Leona, whom I interviewed in the barrio Getafe told me that the elderly woman she took care of died pronouncing her name. Marina, a 43-year-old Bolivian woman who studied geriatrics in Madrid, described the nightly ritual of holding the hands of an elderly person until she fell asleep. Both went on to express that they find power in their work because they do everything “from the heart”, to quote Marina. Similar sentiments were echoed by numerous other informants. Due to limitations of space, I will not delve into the interconnections between warmth, love, solidarity, and gendered latinidad here. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that many of my informants perceive themselves as knowledgeable, which shapes their sense of power.

This felt expertise which translates into felt power is evident not only in elder care but also in the private care of children and individuals with (chronic) illnesses and disabilities. The care work carried out by women such as Leona, Marina, Melany, Anita, and Shirley shapes, guides, and supports families through their embodied and affective expertise in working towards communal and familial well-being. In this blog post, I have introduced the concept of felt expertise to describe such affective fields of knowledge. Employing Whittaker and Million’s framework makes evident that this felt expertise may foster a sense of felt power, particularly during an unprecedented and life-threatening pandemic for both workers and employers alike. While this felt power does not negate the exploitation and systemic issues they encounter, it showcases the resilience and agency of these workers. It also elucidates why Anita felt powerful and strong despite the exploitation she endured upon her arrival in Spain. Recognizing the significance of the affective dimensions of knowledge opens up the possibility to think – and feel – beyond what we know of power in domestic care work. I look forward to further discuss the concept of felt expertise as well as the entanglement of knowledge and power in Catherine Whittaker’s and my upcoming workshop No. 33 at the GAA conference in Munich.

Footnotes

[1] All quotes are translated from Spanish to English by the author.

[2] For an in-depth critique of the use of emotional labour to describe care work, see Hesselmann 2020.

References

Bofill-Poch, S., & Gregorio Gil, C. “Tú no tienes donde ir (y yo sí). De cómo el miedo al contagio impacta en las trabajadoras migrantes empleadas en el hogar.” Migraciones. Publicación Del Instituto Universitario De Estudios Sobre Migraciones, no. 53 (2021): 143-170. https://doi.org/10.14422/mig.i53y2021.006.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Edited by John B. Thompson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Edited by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. “From Servitude to Service Work: Historical Continuities in the Racial Division of Paid Reproductive Labor.” Signs 18, no. 1 (1992): 1-43.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1971.

Hesselmann, Friederike. “Fürsorgliche Liebe als Widerstand: Die Emotion und das Selbst in der Care-Arbeit lateinamerikanischer Haushaltshilfen in Madrid .” Master Thesis, Göttingen: Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3249/2363-894X-gisca-31.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. “Love and Gold.” In Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, edited by Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Russell Hochschild, 15-30. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2003.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

León, Margarita. “Migration and Care Work in Spain: The Domestic Sector Revisited.” Social Policy and Society 9, no. 1 (2010): 409-418.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. Werke, Band 23, “Das Kapital.” Berlin: Dietz Verlag, 1968.

Migration CIDOB, European Union. “Spain: Domestic workers entitled to unemployment benefits.” Accessed May 18, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/news/spain-domestic-workers-entitled-unemployment-benefits_en.

Million, Dian. “Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History.” Wicazo Sa Review 24, no. 2 (2009): 53-76.

Million, Dian. “There Is a River in Me: Theory from Life.” In Theorizing Native Studies, edited by Audra Simpson and Andrea Smith, 31-42. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Rubio, Sara P. “Immigrant women in paid domestic service: The case of Spain and Italy.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 9, no. 3 (2003): 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/102425890300900310.

Sahraoui, Noura. Racialised Workers and European Older-Age Care: From Care Labour to Care Ethics. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Solé, Carlota, and Silvia Parella. “The labour market and racial discrimination in Spain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29 (2003): 121-140.

Wallace, Michele. Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman. London: Verso, 1990.

Whittaker, Catherine. Felt power: Can Mexican Indigenous women finally be powerful?. Feminist Anthropology, 1 (2020): 288-303. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12016.

Friederike Hesselmann is a PhD student at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, Goethe University Frankfurt. Her research interests lie in power, care, health and migration. After completing her B.A. in anthropology and law and writing her thesis on traditional healing in Bangladesh, she focused on private care work and resistance for her M.A. at the universities of Heidelberg and Göttingen. The anthropology department of the Georg-August-University of Göttingen has published Hesselmanns Master thesis: Hesselmann, Friederike. “Fürsorgliche Liebe als Widerstand: Die Emotion und das Selbst in der Care-Arbeit lateinamerikanischer Haushaltshilfen in Madrid .” Göttingen: Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 2021. (https://doi.org/10.3249/2363-894X-gisca-31.) Subsequently, she worked as a research consultant in Berlin. Currently, she analyses (felt) power relations in Spain’s care work sector as a doctoral candidate and works as a legal service manager in Hamburg.