Theseus Sailing the Peruvian Mantaro

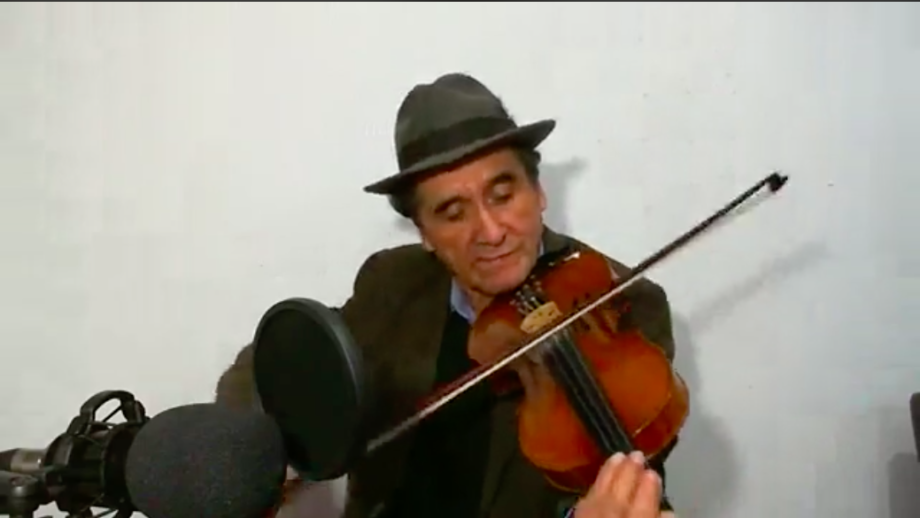

Figure 1: Laya [andean Priest] Zósimo Tapara Jurado, performing a ceremony in the mountain of Huaytapallana, prior to the Coronavirus pandemic. Photo: Joaquín Molina (author).

The Mantaro Valley, crossed by a great homonymous river and located in the central highlands of Peru, has historically been characterized as a unique place in the development of the Andean history due to the symmetrical negotiations that the predominant culture of the area, the Wanka, have maintained first with the Spanish Conquistadores against the Incanato and later on during the colonial period. The anthropologist José María Arguedas has described the region as a place where “se ha realizado el proceso de transculturación más vasto y profundo de la población india en el Perú” ([1953] 2012: 27).

My doctoral research studies the main transcultural processes in the Mantaro region and clearly differentiates it from other “Contact Zones” in Peru, based on both archival documentation and interviews conducted in the field. Special attention is paid to the particularities of its agro-festive cycle and the reciprocal relationships that still underlie its rituals and fiestas. However, due to the current Coronavirus pandemic, my planned fieldwork in the area had to be postponed and modified. Because of this unexpected situation I had to reassess the traditional ethnographic methods foreseen in my original project. Also, I had to challenge the deep changes that the rites and celebrations, which are essential to the Wanka identity, have experienced in the last months… Have my research, my ethnographic methods and the culture in the region under study lost its essence and identity?

The Theseus Paradox

The so-called “Theseus paradox”, first recorded by Plutarch in his The Parallel Livesand later discussed by the philosophers Thomas Hobbes (in Kozakai 2005: 43) and David Hume (1969) is a contradiction that raises a question of identity – whether an object which has had all or part of its components replaced remains fundamentally the same object. In Plutarch’s words:

The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of Demetrius Phalereus. They took away the old timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that the vessel became a standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted question of growth, some declaring that it remained the same, others that it was not the same vessel”.

(The Life of Theseus, 23: 1)

A similar type of paradox is currently being faced by anthropologists since the Coronavirus pandemic started. Due to the actual crisis, Ethnography has largely lost its laboratorium, because of the border closures, travel delays, sanitary measures and governments restrictions that make difficult to carry out anthropological research as we were used to, either locally or abroad. The trend has been to change tape recorders, cameras and notebooks, for distance interviews and phone calls, at best.

In the particular case of my doctoral research in Peru’s highlands, I have been facing unforeseen challenges regarding new and adequate ways to continue with my fieldwork under these unexpected circumstances. In other words, I have been forced to “replace old wood with new wood” meaning that the traditional methods proposed at the beginning of my research, had to be changed for “remote” methods which largely rely on new media technologies. This situation has left me wondering whether I should abandon part of my ethnographic work for the sake of theorizing on the discipline, thus resigning to practical experience.>

Ethnographic and cultural changes

The anthropologist Juan Javier Rivera Andía has recently edited an anthology entitled Non-Humans in Amerindian South America. He introduces this work by defining ethnography as “the prime heuristic in anthropology” (2019: 30), and he also outlines the idea of giving back to anthropology “the loss of the discipline’s distinctive theoretical nerve”, clearly alluding to the of HAU: Journal of Ethnography Theory. But, how can we recover that distinctive theoretical nerve of anthropology, the ethnography, if the pandemic crisis makes it practically impossible?

In fact, it is not only the fieldwork of the anthropologist that has been affected by this global health crisis, but also -and much more relevant- it has been the impact on the normal development of the cultures involved in a variety of studies. My research has suffered considerably challenges since the lock-downs began in Peru, on March 15, 2020. In this scenario, ethnographic work had to switch to remote modes of conducting interviews and to online research for archival work in libraries. Fortunately, I can rely on the fieldwork I made before moved to Germany and started my doctoral studies at the University of Bonn. For now, the data obtained in the field that I have used in the early stages of my research has been sufficient, but this does not prevent the need to having to return to Peru in the near future, given the nature of my project that consists in observing rituals and celebrations in situ

Cancellation of the agro-festive calendar

Despite this, to my surprise, I have discovered interesting research opportunities in the development of the cultural processes of the Mantaro Valley in times of Coronavirus. In a Zoom interview with the anthropologist Yhon León-Chinchilla on October 1, 2020, resident of Huancayo (an area of the valley where I also had to carry out fieldwork) and who has written about the effects of the pandemic crisis in this zone, we shared relevant information regarding the restrictions in the rituals and celebrations that are part of the agro-festive calendar of the Junín region.

León-Chinchilla points out:

“Specific cases are the ‘Haylarsh Huaytapallana Contest’ in El Tambo district and the ‘Wanca Nation’ in Huancayo, the cancellation of all activities related to the Cruz de Mayo, the celebration of the Jija dance, in Jauja; the Fiesta de los Solteritos, and in the province of Tarma, in Acobamba, all the festivities of the period to date. A massive event between July and August, where practically the entire population of the valley participates, is the Santiago in its urban and rural versions, which was also canceled, along with everything that surrounds it: ceremonies of offerings to the local Apus, rural rituals carried out by layas and parades organized by the local municipality and the Decentralized Directorate of Culture of Junín, of the Ministry of Culture. Also, the celebrations in September to the ‘mamacha Cocharcas’, which involve mass pilgrimage and dances, held in Orcotuna and Sapallanga, was canceled. In other words, the entire agro-festive calendar of the Mantaro valley has been abolished”.

The measures adopted in Peru due to the Coronavirus pandemic have caused a complex crisis in the Mantaro Valley that also affects the “cultural industry” associated with these celebrations, insofar as the musicians of the typical orchestras depend financially on traditional festivals. They are all informal workers. The members of the comparsas and the musicians hired in family ceremonies do not have medical or unemployment insurance, which indicates that most of these activities are carried out in a context of informality.

New formats and methods

However, not everything has been about fiesta cancellations in the valley. The Parish of San Pedro de Sapallanga held an eve and a serenade in honor to the Blessed Virgin of Cocharcas that was

Screenshot of Edilberto Paucar Camargo performing a traditional “Santiago” on July 25, 2020. Source: Facebook, musician’s personal page.

On the other hand, on July 24, 2020, there was a ceremony called velacuy organized by the Ministry of Culture and lead by laya Sócrates Zevallos. As is traditionally performed, the laya should hold a container with fruits as an offering to Taita Shanti, while saying: “mother earth, father sun, father wind, mother water, receive this offering from your children of the Mantaro Valley, receive this offering from those of us who are still waiting for you and are your children and thank you, thank you, thank you”. Then, holding a pitcher and pouring chicha to the ground, he says: “Taita Inti, Mama Pacha, Taita Huayra, Mama Yacu, receive this sacred chicha that is the fruit of the gift you give to human beings”.

Figure 3: Screenshot of laya Sócrates Zevallos performing a velacuy ceremony and making an offering to Taita Shanti, spirit of the local Huaytapallana mountain, as seen on the Zoom platform and performed through Facebook Live, July 24, 2020. Source: Facebook page of the Ministry of Culture, Directorate of Junín.

To what extent will the Wanka identity be maintained in the Mantaro Valley as it was known until before the Coronavirus pandemic? Will this generate a conflict of reciprocity between the families involved in the mass celebrations regarding the payments promised to the who live in the mountain, which were not made? Will online rituals completely replace face-to-face rituals in this cultural macro-zone?

Since the theoretical discussion regarding ethnographic methods will undoubtedly vary during the current health crisis and Andean rituals will also change, we can only expect that these true ships of Theseus, namely the ethnography and rituals of the Mantaro, will maintain their essential identity throughout this long period of crisis; the impact of which is still immeasurable due to its magnitude and global scale.

Contribution written on 2 October 2020

My name is Joaquín José Antonio Molina and I have a B.A. in Spanish Language and Literature, M.A. in Arts, mention in Theory and History of Art, both degrees from the University of Chile. I am currently conducting my doctoral research at the Department of Anthropology of the Americas of the Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Anthropology of the University of Bonn, funded by the “Ph.D. Scholarship with Bilateral Agreement Abroad”, from the National Agency for Research and Development of Chile (ANID) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Contact: Joaquinmolina[at]uni-bonn.de

References

HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. n.d. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory [Presentation]. https://www.haujournal.org/index.php/hau/index.

Hume, David. 1969. A treatise of human nature. Penguin Classics.

Kozakai, Toshiaki. 2005. Cambio y permanencia. Identidad colectiva y aculturación en la sociedad japonesa. In: Trayectorias 18 (7), 33-45.

Plutharc. 1914. The Parallels Lives. The Life of Theseus. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Theseus*.html

Rivera Andía, Juan Javier (Ed.). 2019. Non-Humans in Amerindian South America: Ethnographies of Indigenous Cosmologies, Rituals and Songs. New York, Oxford: Berghahn.