Overcoming Distances and Boundaries

Some Reflections on Collaboratively Working with Ethnographic Materials in Germany and Australia

The recent debates around the Humboldt Forum in Berlin have drawn attention to various challenges related to the many ethnographic collections in German museums and other institutions (e.g. archives, universities). The existence of the ethnographic collections, their contents and histories crystallise new questions about Europe’s present and past position in the world. How were these collections acquired? How have they shaped the view of other cultures and of Europe’s self-understanding? For the many specialists working in these institutions, these challenges are not new even if they have been differently articulated through time.

However, the decision to present the collections of the Ethnologisches Museum as well as the Museum für Asiatische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin in the heart of the German capital has suddenly made a much wider audience aware of these elements as well as their links to wider political and historical contexts of continuing and often unacknowledged colonial orientations. That is, these collections draw attention to the role and character of European colonialism and ongoing legacies in various cultural and political fields including within the populations of the countries where these objects were collected. The discussion about the treatment of ethnographic objects today not only concerns questions about provenance research but also issues surrounding restitution and repatriation. They are related to more subtle factors of cultural appropriation. Who has the right to speak about meaning and significance today? Professional anthropologists with insights into the history of the collection and the existing literature or Indigenous people from the regions where the objects were originally made? Should science and academic analysis be emphasised or Indigenous knowledge and authority? Elsewhere, I have recently argued that these questions are crucially important in today’s globalised world and that museums can play an important role in developing intercultural competency (Porr 2017). They can also contribute to fostering a more nuanced and complex understanding of the interrelatedness of German and European history and those places and people that have engaged with in the colonial past.

Tackling great questions needs to start somewhere. Here, I want to provide a few reflections on the practical dimensions of addressing some of the issues mentioned above with reference to a German-Australian project I initiated in 2009 and continue to be involved in.

In 2008, I started working as a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Western Australia. One of the department’s main research regions is the Kimberley in the far north of Western Australia. In terms of archaeological research, this region is one of the more remote and least studied parts of the continent. I noticed very quickly that this region has something of a tradition of German-speaking researchers, mostly in the field of (social) anthropology and in the presence of missionaries. The Kimberley is also widely known for its Aboriginal rock art. As Indigenous art and rock art is one of my main research areas, I became interested in the 1938 and 1939 ethnographic expedition from Frankfurt am Main that had visited the Northwest-Kimberley. Several German monographs were published in the 1950s and a few papers in later years, which were derived from these periods of field work. One English language paper on the rock art was published in 1956. The expedition produced an extensive body of archival materials; photographs, note books, field diaries, art works and a collection of ethnographic objects. It was immediately clear to me that the materials had not been studied or analysed further and that the content of them were virtually unknown to the Aboriginal people of the local communities visited by the expedition members.

In 2009, I received a research grant from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) to undertake research on the bark paintings of this expedition. They are among the earliest surviving Aboriginal art works from this part of Australia and provide invaluable markers for an understanding of the modern Indigenous art history of the region. I could make a full record of the ethnographic objects in question, which are kept and curated at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main. Another element of the project was to identify, a range of related materials and photographs in the Frobenius-Institut. This coming together of information created greater integrity to the collection but work remained to be done. The resulting detailed report, including a digital database, was made available to the appropriate Aboriginal Corporations and the Mowanjum Aboriginal Art & Culture Centre. To date, the greatest interest in reviewing the materials in the report has been among the community members who access and use the art centre where the images and accompanying information inspired further artistic activities and discussion about the materials themselves. Since the first contacts with the Corporations, the Art Centre and individual Aboriginal people, further discussions and consultations have been ongoing and options for future projects and collaboration have been considered including the development of an ambitious project to begin the process of reuniting the expedition materials to consider repatriation through the digitalisation and translation the remaining materials in the various holding institutions. Members of the relevant Aboriginal communities have now visited Germany twice for discussions and the development of research and consultation plans and protocols of engagement with myself and other partners in the proposed research project. One of the visits was to put in place the cultural permissions for the public display of several copied paintings from rock art shelters and reproductions in an exhibition in the Martin Gropius-Bau in Berlin in 2016 and in the accompanying catalogue. The exhibition publication also included a collaboratively-written chapter that details the background to the exhibited paintings of images and the related cultural meanings of those images as well as the relevant cultural protocols associated with displaying them and telling the stories associated with them (Doohan et al. 2016b). We now know that more previously undiscovered archival materials and objects are present in the Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich and the University of Cologne. It is too early or appropriate for me to get into the details of this ongoing work here. However, some of our preliminary results have been published elsewhere, in a paper in the Journal of Pacific Archaeology (Porr & Doohan 2017).

The overall aim of the agreed activities is to come to an understanding of how it could be possible to bring together both analytical western scientific ideas and analysis with Aboriginal knowledge and perspectives. For this to happen it is important for those involved to understand the cultural background and values of the Aboriginal communities included in this collaboration and recognise their own prejudices and limitations. The Aboriginal people are members of the Wanjina Wunggurr community and Traditional Owners of Wanjina Wunggurr Country. For them Country is a cultural construct, a life affirming and enlivened entity. Members of this community comprise a distinct society who share a system of beliefs and practices that sets them apart from other Kimberley Indigenous societies. They see their Country as characterised by the belief in the creator ancestors of Wandjina (anthropomorphic beings also in animal form), Woongudd (the sacred life force Snake) and Gwion (in their various forms including representations of vegetation). Country exists as a rich tapestry of tangible and intangible elements which are derived from actions of creator Beings in the ‘everywhen’ (the past-present- future continuum) of what they call Lalai. In Kimberley Kriol, Lalai is the word that is widely used for ‘Dreaming’, ‘Dreamtime’ and/or ‘Aboriginal Law’. This rich body of religious narratives concerns the core of how and when the land, the sea, the heavens and all that is within them came into existence and continue to exist. The Law and the Dreaming is a framework for social order and engagement with the natural and supernatural worlds, within which patterns of governance, responsibilities, moral order, accountability and entitlements are explicated.

Today, the Kimberley region is widely recognized for these Aboriginal cultural traditions and its extraordinarily rich record of Aboriginal art forms that extends back tens of thousands of years and was added to Australia’s National Heritage List in 2011. In 1992, the High Court of Australia’s made the historic Mabo decision and one year later the Australian Parliament passed the Native Title Act. This act legally recognized that Australian Aboriginal people can claim ongoing cultural and spiritual connections to their ancestral lands and rights to the fulfilment of their responsibilities towards these lands. In 2011, the Federal Court of Australia also determined that Native Title exists across the whole of the Wanjina Wunggurr cultural area in the Northwest Kimberley. The Court therefore confirmed that the respective Aboriginal communities share a unique system of beliefs and practices and that these traditions have survived European settlement and intrusions.

Following the logic of Wanjina Wunggurr culture that people, stories and places belong together and are geospatially relevant throughout the entirety of Wanjina Wunggurr country some of the most powerful evidence of Aboriginal witnesses in their native title claim had to be given to the court at Wandjina rock art sites. This example of the Wanjina Wunggurr Traditional Owners’ response to engagement with cultural practices of the dominant society, giving evidence in a court, demonstrates that Wanjina art sites and the imagery in them is important and accordingly, the reproduction of the rock art in any form is not unproblematic. The images are not paintings in a Western sense and their significance rests in their mythological and local connection to places and stories for which in turn specific local groups and persons have cultural obligations and responsibilities. Even though it is currently not a legal requirement, taking these cultural values into account is an integral part of respectfully working with Aboriginal Traditional Owners and working in their country. The Code of Ethics of any professional organisation that is engaging with Australian Aboriginal organisations, such as the Australian Anthropological Society (AAS), the Australian Archaeological Association (AAA) or the Australian Institute of Australian and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) specifically reference these matters. For instance, informed prior consent must be acquired from the appropriate and authorised person or group before research is undertaken, samples taken, visual or other recordings are made, or reproductions of images are published. The seeking and granting of permission and articulation of agreed research methods and protocols are not only important for ethical reasons; for Indigenous research partners, they are also essential for their continuing cultural, social and spiritual survival.

In my experience, working on the ethnographic materials of the German expedition from the Kimberley has been a constantly, fascinating and sometimes difficult learning experience. It is indeed an ongoing process. Some of the challenges are certainly related to working in a different cultural context. But, some challenges are simply logistical managing many different partners on the other side of the globe all with variable interests and often limited access to means of communication. Below are some personal and specific reflections and points of advice; they will not apply to all circumstances.

Understanding the local administrative and legal context.

In Australia there are a number of different Aboriginal Organisations that represent different groups of Aboriginal people. Some of these representative groups have formal legal status such as Prescribed Body Corporates (PBC) which are derived from the Native Title process and others have less formal standing but are politically powerful in their own right. Regardless of their standing, they are organisations that directly represent the Traditional Owners of different groups and they are usually the authorised organisations to undertake a wide range of negotiations such as with intending researchers as well as mining companies or governments. Before beginning any form of research, it is necessary to submit an outline and potential benefits to the Aboriginal community of the intended work to the relevant corporation’s office. It will then be discussed be the members of the board of directors, who might require further information, a presentation from the researcher or dismiss or agree to the research proposal. This can be a long process, but it is necessary to ensure that all the relevant Aboriginal people are aware of the project and to ensure that all the researchers are also aware of the rules of engagement so to speak. Any research always affects the whole group, directly or indirectly and the research institution.

In the Kimberley, there are a number of representative organisations such as the Wanjina Wunggurr PBC, the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), which was originally responsible for the negotiation of Native Title proceedings and the representation of Aboriginal interests in the Kimberley prior to local Aboriginal groups gaining their native title and managing their own negotiations; there are times when the local organisations and the KLC operate together and other times when they do not. Relations between different Aboriginal groups, individuals and corporations can be strained and unstable. Finally, the Wanjina Wunggurr communities are also involved in a very active and successful community-based art centre, the Mowanjum Art Centre. It often is useful as a meeting point and communication centre. It also has its own corporation and runs a community archive, but it does not directly represent the cultural groups. Nevertheless, the art centre and those working in and through it are interested in and affected by the research project design and delivery. Understanding these different layers of administration and representation is critical but this is always only a first step.

Understanding the local Wanjina Wunggurr cultural context and its specifics.

There are of course disagreements within and between communities and individuals about the administrative contexts and their usefulness with respect to their ability to represent different kinds of interests. These dimensions add another layer of complexity in understanding local situations. One of the key issues is related to the question of authority. As was mentioned above, all materials that the project is dealing with come from specific places and were made by members of particular cultural or family groups. However, individuals can have multiple connections to people and places and this complicates the picture further. In principle, the people with authority are those who have a recognised connection to the country where the images are located and/or the individuals who were interviewed, photographed, drawn or who created the objects that are now in a collection. In practice it is not always easy to determine who these people are and how they are connected. In reality and in terms of appropriate engagement, this is a matter for the representative organisation to determine in consultation with the relevant local group and for them to make the necessary decisions and nominate a representative or representatives to work with the researcher(s). As a researcher, it is sometimes very difficult to get to know the exact relationships between people and place and who can speak for which country and area. Also, these aspects are often contextual, have a certain fluidity and are a matter of debate. Nevertheless, they are very important to get right and to consider, because they are the key aspect to building trust and long-term healthy relationships between community members and researchers.

Consider Indigenous interests.

An essential aspect of the collaborative and decolonising and repatriating work has been to make clear that no pressure is placed on anyone in the decision-making process. Cultural sensibilities are respected, and the authority of our research collaborators is respected as well. This also has to include any information that is generated during the project. It is important to understand that as university- or museum-based researchers one is first perceived as representing the dominant society and people might not be prepared to be immediately forthcoming with important or relevant information.

As a marginalised group, Aboriginal people continue to experience a significant amount of pressure from authorities and different interest groups and stakeholders. Indigenous people have experienced again and again that researchers (as well as a lot of other people) have made significant promises of outcomes and benefits of projects that never materialised. The distance between the research areas and the location of museums and universities often makes the contact between the collaborators difficult. For me, personally, this has been a major source of frustration, because work commitments and travel costs do not allow me to catch up with people regularly. At the same time, I have been told that it is very much appreciated when I regularly return – even if it is not as much as I would like to. Therefore, it is always important to take into account the perspective of research collaborators and their personal perspectives and interests. One should not assume that one’s own project is the most important thing in another person’s life.

Money is important.

Yes, that is unfortunately the case. When discussing research project plans, it is always important to consider the necessary funds of engagement as well as the field exercise. It is very easy to make what become unrealistic promises and generate unrealistic expectations. This aspect can be a bit tricky for researchers (like me!), who have employment and tend to focus on the cultural or academic value of a project as I have imagined it. However, again, Aboriginal people have been in similar situations before in their contacts with researchers as well as commercial players, mining companies and government agencies. Getting the financial aspect right is important, not only in terms of the operation and the outcomes of the project but also in terms of remuneration for research partners. In Australia, it is usually the case that collaborators (who were once unpaid informants) are paid for their intellectual and physical participation in research projects. These are not trivial sums and are currently up to $500 per day per person. There have been some fierce discussions about these fees in the past and accusations of taking advantage of the so-called research opportunities. However, although problems certainly exist, in my experience, these are rather a product of the difficult and often limited circumstances in which our research partners operate. They have paid the price in terms of their time and their knowledge many times in the past and sources of income can be difficult, especially in remote areas. In the end, paying collaborators properly is also a clear sign of valuing their time and their knowledge. Finally, doing fieldwork in remote regions of Australia is incredibly expensive and this is amplified because of the lack of infrastructure such as roads in many research locations. Travel times, logistics and costs can be seen as excessive when compared to other research locations such as say South East Asia or Africa. For instance, to access rock art sites one might require a helicopter which for an hour of time is at least $1,000 and renting a 4WD car (if there are roads) can be up to $200 per day with travel time being at least 5 to 7 days minimum.

Take your time.

It has been a persistent and unfortunate theme of the ethnographic encounter that Indigenous societies or people of the Global South exist in a different temporality and that they operate slower than European people or societies. However, there is much to learn by taking time and that is also true for working with Traditional Owners of the Kimberley region. In my experience, the time-based challenges that arise in the realm of our project work are more related to technical and logistical difficulties associated with getting in touch with people and the necessity of reaching proper and mutually agreed decisions and then reaching the research sites themselves, which are often only accessible for a few months a year because of the weather conditions or cultural limitations.

It is nevertheless important to include the importance of time and consider it in the planning and operation of projects. It is crucial to include time for discussions, explanations and decision-making processes. These are key elements of collaborative and mutual research. Of course, this can be difficult in research projects that have deadlines and fixed expectations in terms of outcomes or publications, which did not take into consideration the time needed to negotiate the research process and undertake the field work itself. These are all issues that make it potentially very difficult to establish and conduct research projects, especially for early career colleagues, who depend on outcomes within restricted timeframes to enhance their career prospects. On a lighter note, once I needed, urgently, a signature from a Senior Knowledge Holder on a copyright agreement for a journal publication. However, my colleague, who was working directly in the town with the community members could only say that our co-author had moved to a new house in a different town and nobody knew where she went or how to contact her. They were still looking for her. Needless to say, everything was sorted out in the end.

Build a strong team.

This last point draws attention to the necessity to build a good and strong team for a project. This sounds a bit like a no-brainer, because every project needs good and involved people. However, we found that it is very important to have a team with different skills and perspectives, both on the side of the researchers and the Indigenous partners. We are fortunate to have a team that involves enthusiastic people in Germany and Australia, in museums, universities, Aboriginal Corporations and in the communities, themselves. I also cannot overstate the role that my colleague Kim Doohan has so far played in the project. Kim is a consultancy anthropologist (and also associated with Macquarie University and the University of Western Australia) and has over thirty years of experience of working with Aboriginal people in the Kimberley. She not only knows the social and cultural contexts but also the relevant Aboriginal people. She is also deeply familiar with the logistical challenges and necessities of working in the region and has spent time in Germany learning about the research field of the German institutions. Finally, because of her ongoing professional work, she can regularly and directly engage with local Aboriginal community members, keep people in the loop so to speak and learn about potentially problematic issues more readily. This is a favourable situation, which, however, depends on a lot of personal investment and energy. Equally, we have been fortunate that Leah Umbagai, a Senior Woddordda woman, has also shown keen interest in the project, has given up a lot of her time to participate in the project and has provided invaluable advice both when at home and also when in Germany. The Mowanjum Art Centre has been a valuable partner from the very beginning and it has provided an important platform and point of contact for our activities (www.mowanjumarts.com). Dambimangari and Wunambal Gaambera Aboriginal Corporations have also provided logistical, financial support and encouragement for the project. Without these involvements and the local support and enthusiasm of Aboriginal people we would not have been able to continue our work and they all have contributed their skills, time, ideas and energy.

Similarly, the German institutions have been very supportive as well throughout. At the Frobenius-Institute, Richard Kuba has been the main point of contact and has been driving the project forward over the years. Peter Steigerwald, manager of the image archive at the Frobenius-Institute, has provided important technical advice and services. At the Weltkulturen Museum, Acting Director Eva Raabe, has been instrumental in providing access to the museum’s collections in Frankfurt and providing advice on collection and exhibition issues. In Munich, Michaela Appel has taken up our collaborative efforts and made it her own with specific reference to the materials from Andreas and Katharina Lommel. We have also so far received funding from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), the German Honorary Consulate in Perth, the German Foreign Office (Deutsches Auswärtige Amt), the Frobenius-Gesellschaft, the Weltkulturen Museum and the Museum Fünf Kontinente.

Together, we will continue our journey of understanding and want to demonstrate that these explorations are best done with a respectful appreciation of cultural differences in a dialogue between Indigenous communities and researchers. We hope to be able to present more results of our work soon, both in academic and popular contexts.

Leonie Cheinmora (left) and Leah Umbagai view a number of painted copies of rock images that were painted by Katharina Lommel in Ngarinyin Country (Kimberley, Northwest Australia) in 1954 and 1955. The copies are kept at the Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich (photo: Martin Porr).

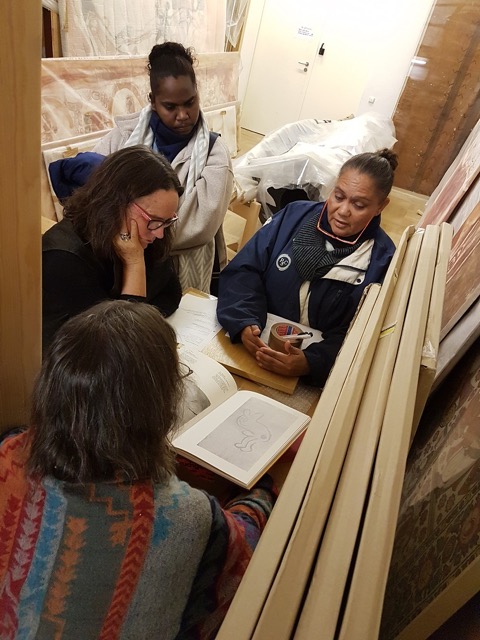

Michaela Appel, Kim Doohan, Leonie Cheinmora and Leah Umbagai (left to right) assess publications from Andreas and Katharina Lommel in the archive of the Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich (photo: Martin Porr).

The Museum Fünf Kontinente houses an extensive photographic archive related to the expeditions to the Kimberley (Northwest Australia). Leah Umbagai (left) and Leonie Cheinmora assess some of the photographs regarding the names of individuals, information about places, and the representation of cultural meanings (photo: Martin Porr).

Martin Porr is Associate Professor of Archaeology and a member of the Centre for Rock Art Research + Management at the University of Western Australia (UWA). He received his PhD from the University of Southampton in 2002. He was employed at the Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte (Halle/Saale, Germany) and was Museum Director of the Städtische Museen Quedlinburg (Germany). Since July 2018 he has been Discipline Chair for Archaeology at UWA. He teaches archaeology at undergraduate and honours level and supervises postgraduate research students.

____________________

References/further reading:

Blundell, V. et al. (eds.) 2017. Barddabardda Wodjenangorddee: We’re All Telling You. The Creation, History and People of Dambeemangaddee Country. Derby: Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation.

Blundell, V. & D. Woolagoodja, 2005. Keeping the Wandjinas Fresh: Sam Woolagoodja and the Enduring Power of Lalai. Fremantle: Fremantle Arts Centre Press.

Doohan, K. & L. Umbagai & J. Oobagooma & M. Porr 2016a. Yooddooddoom: A narrative exploration of the camp and the sacred place, daily life, images, arranged stones and Lalai Beings. Hunter Gatherer Research 2, 3, 345-374.

Doohan, K. & L. Umbagai & J. Oobagooma & M. Porr 2016b. Produktion und Befugnis. Über Präsentation, Repräsentation und die Zusammenarbeit mit den traditionellen Besitzern der Felsmalereien der Kimberley-Region, Nordwestaustralien. In: K.-H. Kohl & R. Kuba & H. Ivanoff & B. Burkard (eds.), Kunst der Vorzeit. Texte zu den Felsbildern der Sammlung Frobenius. Frankfurt am Main: Frobenius-Institut an der Goethe-Universität, 92-105.

Jebb, M. A. (ed.), 2008. Mowanjum. 50 Years Community History. Derby: Mowanjum Aboriginal Community and Mowanjum Artists Spirit of the Wandjina Aboriginal Corporation.

Lommel, A., 1952. Die Unambal. Ein Stamm in Nordwest-Australien. Hamburg: Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde.

Mowaljarlai, D. & J. Malnic 1993. Yorro Yorro – Everything Standing up Alive. Spirit of the Kimberley. Broome: Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation.

Porr, M. 2017. Colonialism, coloniality and opportunities for necessary engagement, critique and reflection. A comment on the current debate around the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. http://www.decolonisinghumanorigins.com/2017/09/commentonhumboldtforumdebate.html

Porr, M. & K. Doohan 2017. From pessimism to collaboration: The impact of the German Frobenius-Expedition (1938-1939) on the perception of Kimberley art and rock art. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 8, 1, 88-99.

Porr, M. & H. R. 2012. ‘Rock-art’, ‘animism’ and two-way thinking. Towards a complementary epistemology in the understanding of material culture and ‘rock-art’ of hunting and gathering people. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19, 161–205.

Petri, H., 1954. Sterbende Welt in Nordwestaustralien. Braunschweig: Albert Limbach.

Schulz, A.S., 1956. North-West Australian rock paintings. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne 20, 7-57.