Colonial Collectors and their Legacy

Why Asking “Why?” Matters

At the time of writing, the conference Museum Collections in Motion lies only weeks in the past and its impacts, its questions and discussions still move me. For all its moments of connection and shared ideals, it was not a harmonious conference. Especially in the beginning, it seemed like mistrust could win over and end the conversation before it had even begun. In the end, the participants’ dedication to the chance this postcolonial moment presents us with was stronger than their differences, but despite the steps taken towards a common vision, some questions remained in tension. One that echoed through many of the debates from the beginning was the search for the role and value of complexity. Around this term, questions about the right way to do science and appropriate ways to speak and feel crystallised into hardened front lines. On one side stood the conviction that attention to detail should be the highest priority in all postcolonial scientific undertaking, even if that meant including and discussing indigenous complicity with the colonial system. Such a perspective, participants argued, gave indigenous actors agency and avoided projecting a perpetual status of victimhood onto them. On the other side, participants questioned the use of such research and called for a clear affirmation of the moral wrongness of colonialism. They feared that too big a focus on complexities clouded the view on the overall reprehensibility and that a search for indigenous agency would at best produce platitudes – of course indigenous actors had agency when they reacted to colonial oppression. In these debates, the term complexity was used variedly, meaning these and other things, yet it seldom felt like those participating in these discussions understood each other – the tension remained mostly unproductive. In this short essay, I want to use my own research on German ethnographer Wilhelm Joest to provide a perspective onto complexity that might allow for a more nuanced and generative discussion. From the divisions of the conference, I want to take a step back to look at the possibilities of what complexity could mean for postcolonial research and a postcolonial museum.

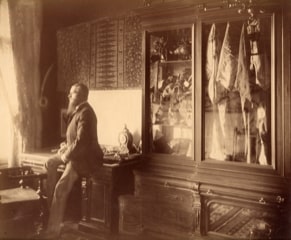

© Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum

Wilhelm Joest was a German collector and ethnographer in the late 19th century, who travelled and collected globally. After his death, his sister Adele Rautenstrauch used his private collection to found the Cologne ethnographic museum that still bears their names today. I came to work with Joest’s field diaries by coincidence when looking for a case study to research the role of masculinity in ethnographic collecting. The wealth of the sources that allow for a close look at Joest’s thoughts, emotions and desires fascinated me and I decided to stay and pursue my PhD at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum. Joest was by no means an exception during his time: he collected depending on and sustaining colonial regimes, his attitudes towards the people he collected from ranged between paternalistic admiration and openly racist hostility and he was repeatedly willing to use violence to get the objects he wanted. Joest, at times, seems like the caricature of a violent, ego- and Eurocentric collector. Yet it is using Joest that I want to make my case for complexity, even when, from a moral standpoint, things seem so clear. I want to frame complexity as the recognition that even someone like Joest had reasons for his actions, motivations based in emotional needs and desires. Even Joest was trying to adapt to the imperial system, even if – and this must always be clear – from a position of power.

Wilhelm Joest did not become the colonial actor he ended up being out of nowhere. To understand why he would traverse the world in search for objects he did not really care about, why he would risk and eventually lose his life doing so, we must look at Joest’s childhood and the frameworks he grew up with. As authors like Jeff Bowersox (2013) have shown, children like Joest grew up in a world that was already saturated with colonialist symbolism and narratives. Adventure literature taught boys that the colonies were a place where one could prove one’s masculinity easily, fighting both the harsh landscape, climate and ‘cannibals and savages’. Thus, when Joest started his first longer journey in the Americas, he already knew what was expecting him – dangerous Indians, subservient companions, and beautiful girls waiting for a white man. And he knew what was expected of him – to be brave and manly, and, if need be, violent. The power of such a seemingly coherent world view, of such a framework of interpretation is strong, especially if one remains in motion constantly, never spending much time with a group or bothering talking to them. Still, there are various instances in the diaries where the imago breaks down, where reality resists and where Joest is left to his own devices, leading to confusion, sometimes actual curiosity, and equally often to violence. In one episode, an indigenous girl of Tierra del Fuego begins to cry when Joest tries to buy her earrings, and Joest, confused and moved by this reaction he cannot make sense of, leaves her alone. Only some days later, Joest is confronted by a confused and drunk indigenous man and spits at him in disgust; throughout the diaries, indigenous alcoholism and trauma remain a conceptual problem for Joest that he cannot fit into any of his categories.

These instances of dissonance continue after the first journey. However, Joest’s self-narrative never collapses. And it is in this stability of the colonial mindset that we find complexity, a tense network of legitimising forces, personal desires and social requirements. Here, I want to look at three of them: masculinity, science and the materiality of objects. The first is imperial masculinity, a gendered belief in one’s own superiority that is coupled with the constant threat of losing it, of being seen as effeminate. His masculine performance pushes Joest beyond his physical limits, consumes female indigenous bodies as proof of his virility, creates a challenge out of every encounter with indigenous men and serves as a source of entitlement to take objects, or use violence, or both. When Joest is at rest and feels superior, he can even admire indigenous masculinities, yet when he starts to feel threatened, he lashes out and the colonial infrastructure of oppressive control shields him from the consequences of his actions. This feeling of power, of agency, is what drives Joest into the colonial periphery again and again, a feeling of worth that he does not feel in Europe, where he feels strangled and emasculated by the social standards and expectations that come with his social position – only in the colonies does he really feel free.

As Joest increasingly professionalises, science becomes an important second frame of reference, that is at the same time deeply entangled with his ideals of masculinity. Science suddenly gives social respectability to Joest’s craving for travel and he expands his collecting to adhere to the standards of Adolf Bastian’s salvage ethnography. As authors like Zimmermann (2003) have shown, invoking science works particularly well when legitimising patronising or violent behaviour towards indigenous populations. There are several instances when Joest takes objects against the will of their owner and even describes the act proudly in his publications as a noble deed in the name of science. Yet invoking science has a second, more personal effect: it also worked to justify Joest’s craving for travel to himself and to his family that would have preferred their son to take over the family’s sugar business. Science in Imperial Germany was, among other things, a career path and once Joest had chosen this way, both his sense of self-worth and his professional success depended on him being able to procure rare and valuable objects. And indeed, once Joest professionalises, he is much more willing to use the threat of violence to get objects into his hands.

The last point I want to mention is the role the objects themselves played in these frameworks of legitimisation. Compared to people, objects made much better projection spaces for Joest’s colonial worldview. They did not talk back and cause disruptions that needed to be reconciled. Instead, through careful selection and arrangement, they could be made to stand for the tenants of this ideology – white technological superiority, a distinction in cultural and natural races, and, in the case of Muslim populations, religious fanaticism vs. Western secular rationality (see, for example, Thomas 1992; Larson 2009; Wintle 2013). Joest could even prove his masculine superiority to himself by collecting and displaying indigenous weaponry as trophies (even though he only bought them in a shop and never fought for them). The second reason why objects worked so well in stabilising visions of the world and one’s place in it was because of their mobility. They could be taken back to the metropole and used there as sources of legitimacy – material proof that the collector was indeed an explorer/scientist/man. It is thus crucial to think collectors and their collections together conceptually, as co-constituted as Helen Verran has suggested in her keynote at the conference. Neither is the collection a mere outcome of the collector’s ideology, nor can it be seen separate from them, and this mutual ability to define and sustain one another is precisely part of the complexity inherent in these collections.

We can see from these episodes that Joest had a variety of reasons to collect. But what are we to make of them, today? A first reflex that I have felt many times while reading Joest’s diaries is to judge the collector and his collecting morally. There are enough instances that allow for a harsh judgement, even according to 19th century standards of morality. However, to determine that Joest was a bad person is not very fruitful, independent of whether it is true or not. It locates the discourses that Joest used to legitimise his behaviour safely in the past and disconnects them from their continuing relevance in the present. And, for white people, judging Joest represents an easy way out that marks a supposed difference from and moral superiority to these past colonial actors. Instead, approaching Joest in his complexity and accepting that he had motivations for his actions may serve as a starting point to search for the continuity of these motivations in the present. The colonial system as it existed at the end of the 19th century is gone, but many of the desires that sustained it are still with us. When reading Joest’s diaries, I sometimes saw myself in him, as uncomfortable as this made me. I was reminded of my time backpacking around the world and of the feelings of agency I connected with being white in the postcolonial spaces of India and Latin America. I also wanted to consume exoticness and transform it into artefacts that I could use to fashion my identity back in Europe. I had different means to do so than Joest, but there is a strong continuity in motivation. It is the moment of discomfort when realising these continuities that really holds the potential for true reflection and a change of mind. But for this to happen, one must get close to Joest and see uncanny likenesses appear. This, in turn, is only possible if Joest remains a person, in all his complexity, and is not reduced to a colonial bogeyman. After all, Joest was often utterly unaware of the violence he was perpetrating or the damage he was causing because his referential framework held so tight. In all his diaries, Joest never really questions himself; moments of emotional confusion like his encounter with the indigenous girl mentioned earlier never start a thought process, they slip past without getting traction on some epistemic foundation that would have allowed some form of self-reflection. If there is a definite difference between Joest and me, then that today I do have such a foundation, a postcolonial theory that allows me to face myself in the mirror of history. And in my opinion, providing this epistemic point of reference and this chance for introspection to other (white) people must certainly be one of the functions of a truly decolonial museum.

There are two points that I want to take away from this. Firstly, that when we speak of the necessity for white people and museums to listen, then this means not only listening to PoCs. It also means to listen proactively within, to question one’s own motivations and desires. During the conference, some speakers seemed uncomfortable when faced with emotional reactions by the audience, showing the continued belief that scientists should not feel emotional attachment to their objects and topics of research. Yet these emotions are there and to deny them almost feels ridiculous – how can one spend so many hours of one’s life with something without getting attached emotionally? To dissolve the juxtaposition of complexity and justice, we also need to dissolve the opposition of emotion and science. Yet one cannot listen if screamed at and emotionality needs safe spaces. Accusations levelled at potential allies destroy such a space. In the worst case, white people will retreat from the public discussion, only to voice their hurt when feeling ‘among themselves’. To allow for complexity in our subjects of research and to allow for complexity among ourselves goes hand in hand.

My second point is that the solidarity that can be achieved in such spaces is in dire need. Some parts of Joest’s observations read uncannily contemporary:

“In this strict adherence to the rules of fasting during Ramadan, […] observed by millions of religious followers, part of Islam’s thorough grip on its many believers becomes visible, and equally the grave danger that Islam could pose, would it start to act as a united political or military force. […] The inhabitants of the Sahara and the Sudanese fast alike, the Chinese Muslim in Yunnan fasts like the Malay in Indonesia – they all follow without a single complaint the teachings of the prophet. And with the same blind reverence they would follow any order by some new false or true prophet who could unite they in a common struggle against abhorred Christianity” (Joest 1895, 274).

Later on in that passage, Joest brings these thoughts on the imminent danger of a Muslim insurrection to their, to him, logical conclusion; he recommends genocide as an appropriate policy to regain control over the Muslim uprising in Aceh. Joest’s writings and his actions show that violence begins with a framework of support and legitimisation. Even Joest shows moments of doubt where he feels guilty for the destruction caused by Europeans. Yet he always ends up suppressing his doubts, soothing his bad conscience with ideals of European civilisation and benevolence. We live in a time where a global regime of violence, similar to that of colonialism, seems once again a realistic possibility. However, the decolonial museum might be a place where the foundations of this violence might still be fought and eroded. Here, we might be able to build alliances against that violence, based on a common goal rather than identity. This is why we must search for complexity when engaging our shared colonial past. We have to ask why people like Joest did the things they did and do our best to use the answers to these questions to stop them for happening ever again.

About the Author:

Carl Deussen studied Liberal Arts and Museum Studies at the University College Freiburg and the University of Amsterdam. He is currently working on his PhD at the University of Amsterdam and holds a research position at the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne.

Sources:

Bowersox, J. (2013). Raising Germans in the Age of Empire: Youth and Colonial Culture, 1871-1914. Oxford University Press.

Joest, W. (1895). Welt-Fahrten: Beiträge zur Länder- und Völkerkunde, Erster Band. Berlin: A. Asher.

Larson, F. (2009). An Infinity of Things – How Sir Henry Wellcome Collected the World. Oxford University Press.

Thomas, N. (1991). Entangled Objects – Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Harward University Press.

Wintle, C. (2013). Colonial Collecting and Display – Encounters with Material Culture from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Berghahn Books.

Zimmermann, A. (2003). Adventures in the Skin Trade: German Anthropology and Colonial Corporeality. In G. Penny & M. Bunzl (Eds.), Worldly Provincialism: German Anthropology in the Age of Empire (pp. 156–178). University of Michigan Press.