Some Joys and Sorrows of Co-Producing Knowledge with Ethnographic Collections

Collaborative research is one way of responding to calls for decolonizing ethnographic collections in addition to or as an alternative for repatriation and restitution. The collaborative approach focusses on inclusivity, symmetry, and sharing instead of arguing for one-sided ownership rights to collection holdings. Assumed benefits include a richer cultural heritage based on diverse perspectives alongside more ethical engagements with collections based on impacted communities’ voluntary, informed, and negotiable participation as well as the production of research outcomes that are beneficial to them (Fluehr-Lobban 2008). Co-producing knowledge, according to the call for papers for this blog, goes beyond collaboration by emphasizing shared authorship and ownership, mutual accountability, and the active engagement of human and non-human actors in the creation of knowledge as well as by reflecting on how power dynamics and diverse epistemologies shape the research process and its outcomes.

In practice, the degree to which these objectives are achieved is quite different and ranges from new forms of (exploitative) knowledge extraction to far-reaching control over all stages of a research project by members or descendants of the communities of origin (e.g., Ames 1999; Boast 2001; Carpentier 2015). The issue of the inclusion of some and the exclusion of many people within the collaborative process remains largely unsolved (Bergold and Thomas 2012; Onciul 2015), particularly when communities do not have firmly established and generally recognized institutions.

My own experiences in co-producing knowledge with the Khwe collection in the Oswin Köhler Archive is a case in point. Despite many benefits for all those involved, the collaboration also resulted in some quite harmful experiences for my collaborators and me. These experiences shed light on how local ideas and power dynamics can challenge scholarly ideals of sharing.

It is important to note that although this contribution is about co-producing knowledge in a collaborative project, it is, itself, not a collaborative product but rather written from my personal understanding as the responsible research fellow. This also applies to what I write about the joys and sorrows of my Khwe counterparts, which I reproduce here as I understood and interpreted them.

Appreciating Belongings

The collection in question was compiled by the German Africanist Oswin Köhler (1911-1996) among the Khwe, an indigenous Southern African population of former hunter-gatherers or San, living in what today is Bwabwata National Park in northeastern Namibia. Köhler worked among the Khwe from 1959 to 1992, meaning he worked mostly during the years when the country was under South African rule and, thus, in a colonial context.

The collection is the world’s largest assembly of belongings from the Khwe, consisting of texts for a vernacular encyclopaedia, photographs, film footage, sound recordings, ethnographic objects, drawings, plant samples, and dossiers. I use the term “belongings” instead of “artifacts” or “items” because it connotes that they were and continue to be related to people and places (Widlok et al. forthc.), and rightfully belong elsewhere, namely back in their communities and families (Muntean et al. 2015; see also Turner 2020, 195). In fact, the degree to which some belongings which I saw as most inconspicuous, such as crumbly plant remains, were valued by my Khwe counterparts confirmed my conviction that ethnographic collections belong to the people for whom they are most important and meaningful instead of to collection holding institutions abroad where they all too often remain unexplored.

The collection holding institution in this case is the Oswin Köhler Archive, a research and documentation platform for academic legacies of scholars in African languages, established by the donation of Oswin Köhler’s academic legacy to the Institute of African Studies at the Goethe University Frankfurt by his widow, Ruth Köhler (1920-2004) in 2000. I have been working as a research fellow in the archive since 2015, first in an editorial project to finalize Köhler’s vernacular text collection on diverse aspects of Khwe culture (Köhler 1989-1997, 2018-2021) and since 2021 in a collaborative project that combines a historically contextualizing and decolonizing approach.[1] The project traces how the belongings came into being by scrutinizing them for signs of work routines and concepts applied to them and by consulting archival files and eyewitnesses. It also historicizes and questions the academic categories which Köhler applied to the belongings, not necessarily to invalidate them but to unsettle their self-evidence (Daston and Galison 2007) and relate them to Khwe ideas and categories. Finally, it looks at how the collection holdings can be made useful and beneficial for the Khwe.

The seed for such a project was planted when I was doing my PhD research on social change at the turn of the millennium (see Boden 2005). Because Köhler had been a professor at the University of Cologne and I was employed at that university at the time, many Khwe individuals approached me asking for possibilities to access the Khwe belongings that Köhler had taken to Germany, photos of people being most in demand. At the time, however, no one had access to the belongings as they were still at Köhler’s home in Cologne.

Recognizing Relations

Köhler was explicitly interested in documenting “traditional” cultural practices which he considered to be endangered, in particular by the militarization of Khwe society in the 1970s and 1980s when the South African Defence Forces (SADF) ran several military camps in the Khwe settlement area in Namibia and recruited many Khwe men as soldiers into their ranks. The fact that the South African administration allowed Köhler to continue his research in the vicinity of what became a military no-access and border war zone was certainly related to the fact that he had been employed as a government ethnologist in Namibia from 1954 through 1957 and proven his “impeccable conservative credentials” (Gordon 1992, 158). Köhler’s goal of salvage documentation (e.g., Köhler 1989, VII-XI) went hand in hand with his opportunistic approach towards the South African administration, which had no interest in publicizing Khwe experiences in the military camps, let alone in military operations (e.g., OKW 325-1).

In spite of the colonial context, Khwe have never expressed any accusations to the archive or me that Köhler compiled the collection illegitimately so far. If at all, critique related to things which Köhler had not collected and, therefore, were not available to represent Khwe culture. It might be noteworthy here that Köhler paid his co-workers for their language work as well as other jobs necessary for running a research camp, such as for the collection of plant samples, the production of artefacts, although not always for taking pictures, and making video and audio recordings. Furthermore, he supported them and their relatives in many ways (Boden 2024), which, among other things, fueled the expectations that Khwe coworkers had of the researchers who followed him.

My Khwe collaborators perceived their culture and language as being highly endangered and appreciated Köhler’s efforts to document them. They understood the collection as a means of learning about and teaching Khwe history and traditions. This is obvious from statements saying that young Khwe would not be able to know their past (Chedau et al. 2023b, 5) or that the Khwe would have lost their traditional culture completely if Köhler had not documented it (ibid, 40).

Indeed, the apparently undivided appreciation for Köhler’s work among the Khwe and the authority ascribed to him, for example, when claiming that he knew the Khwe language better than the Khwe themselves, at first sounded rather irritating to my critical ears of a later generation researcher. This view of Köhler is certainly due to the long-term relationship he had with the Khwe, lasting for a period of more than thirty years during which Köhler spent, in sum, a total of about six years on site (Köhler 2018, 11). This relationship obviously also involved mutually recognizing and being lenient towards each other’s weaknesses or less pleasant behaviours such as the quite restrictive rules of access and conduct which Köhler enforced in “his” research camp and, on the other side, the alcohol drinking tendency of Köhler’s most important field assistant (Boden 2024). The importance of intimate and long-term relationships also became evident during our own collaborative work as the quote below reveals:

It was our decision to stop there and not share all the information [on the effects of medical plants]. For me, it was good not to share all the information. Many people want to have full information and then use it. We do not know how they are thinking. But we did not hide the information from the people we work with because we know them. (Thaddeus Chedau, Frankfurt, 26.9.2019).

That the belongings were safely stored and preserved in the Oswin Köhler Archive was likewise recognized. However, the interview questions which Khwe visitors to the archive posed to its former and founding director of the Oswin Köhler Archive as well as to other academic companions and students of Köhler revealed that they did not necessarily transfer the authority and legitimacy they attributed to their long-term ethnographer to the institution that bears his name. For example, they asked how the Goethe University acquired the belongings and whom Köhler had entrusted with the continuation of his work. They also asked for financial support for a cultural center as well as other activities, such as reviving their culture and traditions, preserving their language through orthography classes in Khwe, building a Khwe radio station, and giving money to the Bwabwata Khwe Custodian Committee (BKCC), an organization which engages in these kinds of activities.

Khwe visitors to Frankfurt as well as Khwe community members in Namibia envisage a repatriation of their belongings in the future but have not (yet) launched an official request, which they said would only make sense once a cultural center was built to safely keep them back home. Digital copies of photographs, films, sound recordings, and texts have been provided to the Bwabwata Khwe Custodian Committee, dedicated to preserve and promote Khwe language and culture and my main local counterpart institution.

Rendering the Collection Beneficial for Community Members

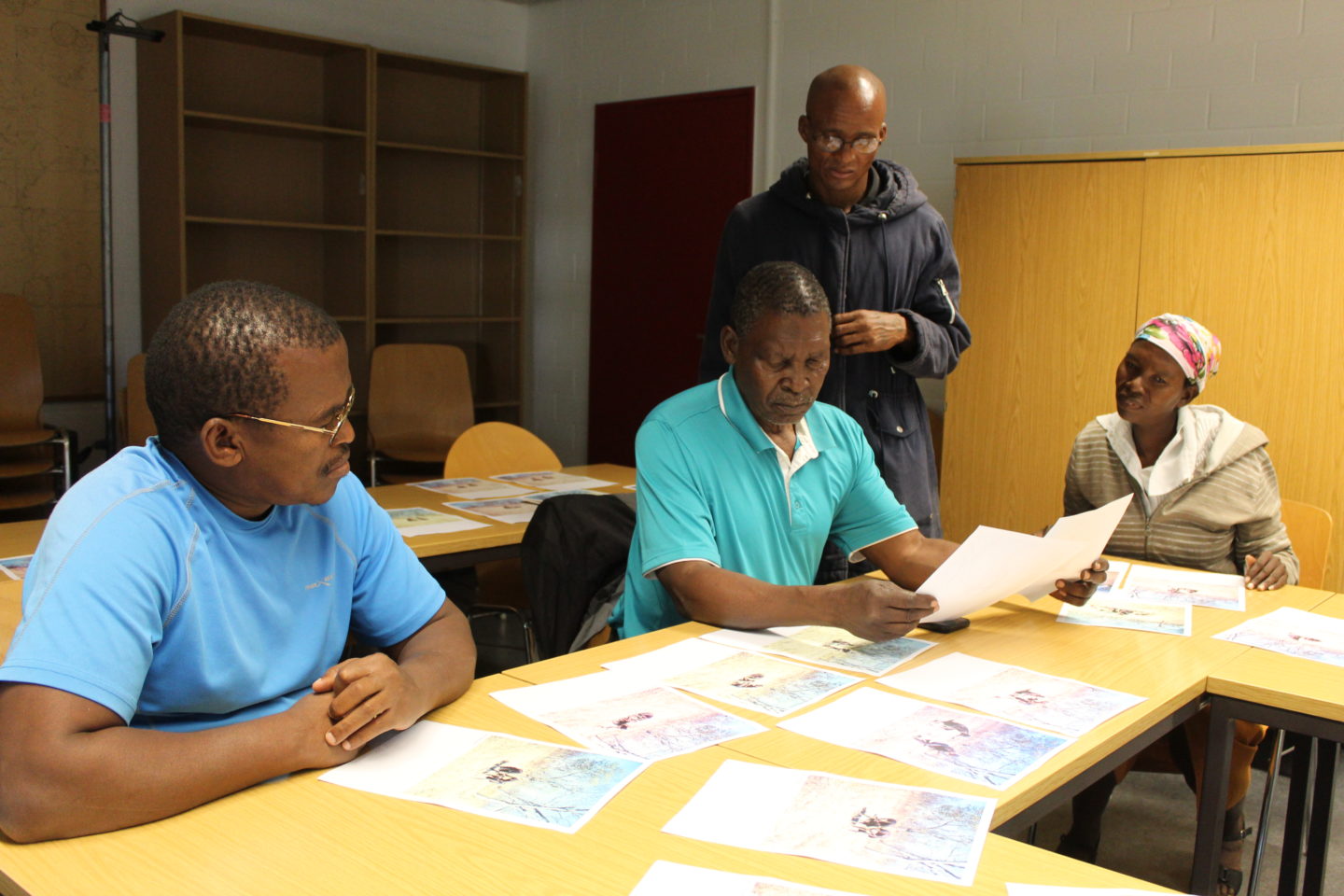

Our collaborative work so far included fieldwork with digital copies of belongings taken to Namibia, presentations and discussions on site in Namibia, and two workshops with Khwe visitors to the Oswin Köhler Archive in Frankfurt.

In 2016, I applied for funding from the Jutta-Vogel-Stiftung in Cologne to work in a participatory project on the film footage as a first step to make the Khwe belongings accessible to the community. First published with only Khwe comments on DVD, the films were later equipped with English subtitles at the request of several Khwe (Boden [2016]2019), when, with support from the Centre for Interdisciplinary African Studies (ZIAF) and the Ubuntu Foundation in Switzerland, I facilitated a first workshop with two Khwe men in Frankfurt. During their stay, they also curated an exhibition that was later transformed into a mobile version to be shown on site in Bwabwata National Park (Chedau and Geria 2019a). In 2023, after a pause caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, I organized another visit of four Khwe, one woman and three men and funded by the ZIAF alone, during which we complemented the mobile exhibition with additional roll-up posters (Chedau et al. 2023a). The additional posters show and provide information on historical photographs selected by the Khwe visitors as well as additional culturally important belongings which community members had missed in the first edition as they were not part of Köhler’s collection. Filling the gaps was possible by including photographs from respective belongings held by the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne, originally also collected by Köhler and a private collector.

Other products developed during these workshops included an audiobook with text from the encyclopaedia read by Khwe speakers (Chedau and Geria 2019b) and a booklet with historical photographs with comments by Khwe workshop participants (Chedau et al. 2023b). In response to a request from Khwe community members and with funding from the Jutta-Vogel-Stiftung and the Institute of African Studies of the Goethe University Frankfurt, we most recently held an orthography workshop and produced an orthography primer (Geria et al. 2025). With funding from the diverse aforementioned institutions, it was also possible to provide hundreds of copies of the DVD, audiobook, and booklet within the community. In 2024, the ZIAF funded the presentation and discussion of the products in different Khwe villages. Although that application formally had to be in my name as a staff member of Goethe University, the Khwe visitors to Frankfurt in 2023 articulated the aim and scope of the application, since they wanted to share ideas within the wider community.

All of these activities and products are beyond the usual academic portfolio and required additional funding efforts as they were mainly meant to serve the Khwe. All reflect Khwe ideas and interests to some degree, but there was a continuous increase in both the demand and initiative for workshops and products as well as authorship and control by Khwe collaborators over the years. This is reflected in the author and copyright details as well as in the amended editions of the DVD and mobile exhibition. During the process, my role changed from that of a researcher who wanted to involve Khwe and provide them access to their belongings to a facilitator who increasingly responded to and implemented their requests.

Enjoying and Suffering from Collaboration

Overall, I would say that sharing perspectives and combining knowledges was a rewarding and inspiring practice for all involved.

Seeing the films, photos, artifacts, and other belongings and listening to the recordings was a joyful experience for workshop participants and other community members, and the fact that the belongings had been inaccessible for years seemed forgotten.

Workshop participants appreciated that they learned how to work with archival materials, write project applications, and produce media to present their cultural heritage.

From an academic perspective, the collaborative work definitely generated a richer cultural heritage, yielding new perspectives as well as lots of additional information on the belongings.

From my personal perspective, serving the Khwe by supporting applications as well as facilitating workshops and the development of products according to their own ideas was very satisfactory.

On the painful side, the Khwe who came to Frankfurt felt it a burden to decide how to represent their culture just by themselves and had to face jealousy and hostilities from other community members who questioned their legitimacy. Furthermore, both they and I were accused of lining our own pockets.

Bearing the Burden of Responsibility

The Khwe visitors to Frankfurt often said that they felt uncomfortable with the responsibility of deciding on content matters just by themselves and would have preferred to be able to consult other community members when discussing, for example, whether certain belongings were of Khwe origin and should be used to represent Khwe culture, or if they should be publicly accessible. This was also the reason why they suggested to apply for money that allowed for the presentation and discussion of the products in all villages back home (see above).

It might be worth noting here that the Khwe society, like other so-called egalitarian societies, are known for their reluctance to take on prominent positions and responsibilities out of fear of being exposed to jealousy, critique, accusations, and hostilities (e.g., Boehm 1993). However, at least during the presentations of our collaborative products that I witnessed myself, such fears seemed to be unfounded. Instead, the audiences generally expressed much appreciation for the work done by my collaborators, different views on certain details notwithstanding.

Being Challenged about Legitimacy

Much more painful and difficult to solve was the selection of Khwe coworkers, in particular for the workshops in Frankfurt. The conflicts arising in this context reflect differences between local perspectives and values and those of the researcher as well as the relevance of local power dynamics.

For the fieldwork in Namibia, I approached different groups of people in diverse constellations, dependent on their expertise. For example, I worked with people who lived at Köhler’s two research sites, Mutc’iku and Dikundu, for identifying people and image contents. For the work on the Khwe correspondence between Köhler and his late field assistant (Boden 2024), I worked with people who had witnessed the life and work in the research camp and were able to provide background information on the letters’ contents. For the work on the film footage, I asked elder people who had witnessed Köhler’s early research trips to Mutc’iku in the 1960s; this was the sole time he shot films. Among the elders in the work group, was one old woman who performed a musical instrument on camera as a teenager. This all goes to say that I was looking for people with expertise in certain areas. Somewhat naturally, they were at the same time relatives of Köhler’s coworkers who have all passed away.

The qualities I was after when inviting Khwe collaborators to Frankfurt with the limited financial resources available were proficiency in writing and reading the Khwe language and a proven commitment and interest in working on Khwe language and culture in addition to formal criteria like possession of a travel document. Given that the Khwe do not (yet) have a recognized central leadership and community meetings were too time- and cost-consuming in an overall poor community living scattered over a large area, the Bwabwata Khwe Custodian Committee was the obvious institution for me to approach. The committee was formed in 2012 to negotiate a Biocultural Protocol (BCP) that articulates community-determined values, procedures, and priorities as the basis for engaging with external stakeholders, such as governments, companies, NGOs and academics and, more generally, to preserve and promote Khwe language and culture.[2] Like other Khwe committees and institutions, its members are people who have made a name for themselves in this field. This includes individuals who, for example, initiated a living museum or were engaged in Bible and other translations. Further members were elected to ensure gender balance and the involvement of representatives of different villages.

My approach of looking for people with such expertise, however, was fiercely challenged by relatives of Köhler’s Khwe coworkers who were supported by people unhappy with members of the BKCC already representing the Khwe in other contexts. They claimed that the relatives of Köhler’s coworkers should be the first or only ones to control access to the belongings and benefit from working with them.

As long as the work took place on site in the Khwe villages, the dissatisfied stayed more or less silent, although the selection of coworkers did not remain completely unchallenged even then. For example, even though the members of the work group for the film had been nominated collectively after a public film showing in the very village where it had been shot, younger relatives of people with whom Köhler had worked closely but who were too young to be eyewitnesses themselves complained that they were not included. At the time, these complaints seemed negligible to me, knowing that it is impossible to please everyone and because the elders in the work group did not want to get into the complaints. Compared to what happened when it came to the selection of Khwe visitors to Frankfurt, these earlier complaints were moderate, although far from negligible in hindsight.

Before the first trip, I asked members of the BKCC to select four individuals with the above-mentioned requirements (i.e. literate in Khwe, committed to such work, and in possession of a passport). Aware of how nowadays local dynamics influence the formation of such groups, I also suggested that the selection should represent different genders and villages. On the list I received were two male committee members and two women, representing different villages and families. However, when preparing the trip, me as well as the selected individuals were challenged and intimidated in ways that made the two women pull back, and I decided to invite only the two men who assured me that they were not afraid of the consequences. The second time, again with a financial limit allowing for only four collaborators, I decided to relieve the Committee from such charges and take on the responsibility for selection all by myself. However, this did not change much as the committee members still had to face complaints and hostilities. I decided for the two experienced men again plus one woman from the family Köhler had lived with in Mutc’iku and one man from the group Köhler had lived with in Dikundu. I also made it a requirement that the people had at least basic knowledge of English so that not every word had to be translated back and forth since my own knowledge of Khwe is, unfortunately, still quite limited in conversations, if not in reading and writing.

I am ready to disclose that for me, personally, working with the committee members was particularly comfortable and easy-going because I had previously worked with three of the frontline figures during my PhD fieldwork and beyond. On the other hand, this long-standing familiarity was also an obstacle and made our collaboration suspicious for those who disputed the legitimacy of the committee with respect to the collection as well as more generally. I am further willing to admit that I was reluctant to change or give up well-established, reliable, and effective work given the investments in work and personal relations involved.

Placing the Collection within Local Power Dynamics

In spite of the positive image of Köhler held and conveyed by all of the Khwe to whom I talked, the way the collection came into being created many challenges for our collaborative work, becoming a non-human actor with great impact and of which full use was made in local power dynamics.

Like any other so-called “collection,” the Khwe collection in the Oswin Köhler Archive is, of course, a “selection,” dependent on and shaped by diverse human and non-human actors in a particular spatial and temporal environment. Elsewhere (Boden 2018), I have described how Oswin Köhler, his so-called “sources” [Gewährsleute], and a multitude of other agents, including the climate, logistical conditions, and macro- and micro-political conditions, have shaped the collection, which in turn shaped and continues to shape our collaborative work.

Scholarly critique of Köhler’s approach of salvage documentation focussed on his assumption of a cultural consensus and the age, gender, and regional biases of his coworkers (Boden 2014). That Köhler preferred to work with elder Khwe is understandable given his approach of salvage documentation. Why he only worked with men he did not explain, but he did so even when discussing topics such as pregnancy, birth, and menstruation. While gender balance is a political issue today, straightforward critique of Köhler in this respect was absent. Criticism was only voiced when I questioned Köhler’s practice of excluding women. Indeed, I felt to be more critical towards some of Köhler’s practices than my Khwe counterparts and often had the impression that I had provoked critical comments without being able to tell whether the earlier silence or the subsequent critical comments represented the personal opinion of an interlocutor. Köhler’s regional focus, in contrast, evoked some critique which I had certainly not provoked. Khwe from the eastern parts of the Khwe settlement area, for example, missed images of their relatives or argued about dialectal differences while, for me, the military closure of large parts of the Khwe settlement area in the 1970s and 1980s sufficiently explained Köhler’s regional focus.

The most palpable and challenging impact arising from Köhler’s selection of a Khwe team was that their relatives claimed that they should be the ones to deal with, decide on, and benefit from the collection. In my understanding, this was more a matter of playing out local power dynamics than a matter of claiming ownership over knowledge. Often, the very people making such arguments turned out to not have the required knowledges and skills. For example, they could not explain how to make an artifact or how to use a plant, they could not illuminate abandoned cultural practices recorded in image and sound, they were unable to detail the meaning of antiquated concepts used in texts or provide advice on the correct spelling of so-far undocumented Khwe words, and they were not eye-witnesses to the work of Köhler and his coworkers in the research camp. Furthermore, they often did not attend our public presentations and discussions, only to complain afterwards that they had allegedly been excluded.

The idea of reserving the dealings with the belongings for the relatives of Köhler’s coworkers was contrary to what other Khwe, the funding organizations, I, and Köhler himself had in mind, the latter having documented the Khwe language and culture for the academy in the first place but also for future generations of Khwe. It would also mean to extend Köhler’s biases to the present or even to the future. My “solution” to the problem has so far been to try and balance requirements concerning expertise, the objective of Köhler’s legacy, local ownership claims, and the interests of the wider Khwe community, a solution that I know will keep being challenged and have to be modified according to future challenges.

Facing Accusations

Apart from questions of legitimacy, we also had to face accusations that we were lining our own pockets. Köhler’s collection donated to the Goethe University does not contain any financial assets to hand out. However, this is what the relatives of Köhler’s coworkers kept claiming and what Köhler seems to have suggested by telling his coworkers that they and their families would be cared for even after he left the field.

It is, generally, much more difficult to prove that something is non-existent than to prove that something exists. Accusations that my collaborators “eat” the money that Köhler allegedly provided for the relatives of his coworkers persist. This is so even though two such relatives were among the four individuals who travelled to Germany in 2023 and were able to see with their own eyes what is and happened in the archive.

Another accusation was that we would allow commercial uses of specific belongings, such as Khwe knowledge on medical plants, and would arrange to profit from such transactions or businesses. Again, it is difficult to prove that neither they nor I pursue such plans or projects, and rumors kept popping up repeatedly. Fears that outsiders might somehow make money from the belongings have so far prevented the original documents from being accessible online, something quite undesirable for donors who, for example, funded the production of digital copies.

However, even though neither money left behind for the relatives of Köhler’s coworkers nor a plan to make money out of the belongings exist, there were, of course, other benefits involved, namely the wages or daily allowances paid to coworkers and the rare opportunity for Khwe people to travel to Germany. Given the overall poverty of the Namibian Khwe (Dieckmann and Jones 2014), one can easily understand that they seize every occasion to claim possibly available financial benefits. In any case, both the assumed and the real financial benefits have fueled the confrontations.

Conclusions

Silvester and Shiweda (2020) have argued that despite the positive assumptions, collaboration can also be disadvantageous for descendants of communities of origin, be perceived as unjust, and entail complex micro-political conflicts. The power dynamics that affected our collaborative work are a case in point. They were less a matter of structural power relations between the collection-keeping institution and “the community” than a matter of power conflicts within the latter. From a scholarly and donor perspective, including local people without much relevant expertise increases costs and hampers the effective achievement of tangible results within fixed time schedules. In the present case, it nevertheless seemed to be appropriate in order to reduce strains on relationships, balance out power dynamics, and ease the burden for committed and knowledgeable coworkers. Decolonizing collections also requires openness to alternative decision-making processes and timings (Mountain Horse and Brown 2019; Onciul 2015) and the recognition that collaboration is not a final solution but a process (Pratt 1991). In my view, the joyful and satisfactory experiences of collaboratively producing knowledge outweigh the pains for those actively involved, if certainly not for every member of a community of origin.

References

Ames, Michael M. 1999. “How to Decorate a House: The Re-negotiation of Cultural Representations at the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology.” Museum Anthropology 22 (3): 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1525/mua.1999.22.3.41.

Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. 2012. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 37 (4): 191-222. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801.

Boast, Robin. 2011. Neocolonial Collaboration. Museum as Contact Zone Revisited. Museum Anthropology 34 (1): 56-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01107.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01107.x.

Boden, Gertrud. 2005. Prozesse sozialen Wandels vor dem Hintergrund staatlicher Eingriffe. Eine Fallstudie zu den Khwe in West Caprivi/Namibia. PhD diss. Universität zu Köln. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/1595/1/BodenGertrudDissertation.pdf.

Boden, Gertrud. 2014. “Oswin Köhler: Beiträge zur Ethnographie der Khwe (Kxoé).” In Ein Leben im Dienste der Afrikanistik. Oswin R.A. Köhler zum 100. Geburtstag, edited by R. Voßen. Rüdiger Köppe.

Boden, Gertrud. 2018. “The Khwe Collection in the Academic Legacy of Oswin Köhler: Formation and Potential Future.” In Research and Activism among the Kalahari San Today: Ideals, Challenges, and Debates, edited by R. F. Puckett and K. Ikeya. Senri Ethnological Studies 99. National Museum of Ethnology. https://doi.org/10.15021/00009123.

Boden, Gertrud, ed. [2016]2019. Tá-khòè-nà di kx’ṹĩ̀ à ǂúu-can-a-xu-a-hĩ Dr. Köhler (“Khwedam”) ka 1962 na 1965 ci ki. The life of the old Khwe recorded by Dr. Köhler (“Khwedam”) in 1962 and 1965. DVD 55 min and brochure. 2nd ed. with English subtitles. Frankfurt: Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Boden, Gertrud. 2022. “Whose Information? What Knowledge? Collaborative Work and a Plea for Referenced Collection Databases.” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 18 (4): 479-505. https://doi.org/10.1177/15501906221130534.

Boden, Gertrud, ed, with assistance from Hendrik Mbangu, Rosna Xoe-tco Gombo, and Thaddeus Chedau. 2024. An Annotated Edition of the Khwe Correspondence between Ndo Tinene and Oswin Köhler 1979-1995. Translated by Gertrud Boden with assistance from Hendrik Mbangu, Rosna Xoe-tco Gombo, and Thaddeus Chedau. Veröffentlichungen des Oswin-Köhler-Archivs 4. Rüdiger Köppe.

Boehm, Christopher. 1993. “Egalitarian Behaviour and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy.” Current Anthropology 34 (3): 227-254. https://doi.org/10.1086/204166.

Carpentier, Nico. 2015. “Differentiating between Access, Interaction and Participation.” Conjunctions. Transdisciplinary Journal of Cultural Participation 2 (2): 7-28, https://doi.org/10.7146/tjcp.v2i2.23117.

Chedau, Thaddeus, and Sonner Geria. 2019a. Khwe Stories and Texts. Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Chedau, Thaddeus, and Sonner Geria. 2019b. Bwabwata Khwen di ǁéúkàkuxú à – Things from the Khwe of Bwabwata to Show Others (Mobile Version). 1st ed. Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Chedau, Thaddeus, Sonner Geria, Snelia Mangonga, and Hendrik Mbangu. 2023a. Bwabwata Khwen di ǁéúkàkuxú à – Things from the Khwe of Bwabwata to Show Others (mobile version). Extended 2nd ed. Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Chedau, Thaddeus, Sonner Geria, Snelia Mangonga, and Hendrik Mbangu. 2023b. Kyárékara mṹũ̀ Khwena di ngyɛ́xuahĩ kx’ṹĩ̀ à. Looking Back to the Past Life of the Khwe. Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Zone Books.

Dieckmann, Ute, and Brian T. Jones. 2014. “Bwabwata National Park”. In “Scraping the Pot:ˮ San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence, edited by Ute Dieckmann, Maarit Thiem, Erik Dirkx, and Jennifer Hays. Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Foundation of Namibia.

Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn. 2008. “Collaborative Anthropology as Twenty-first-Century Ethical Anthropology.” Collaborative Anthropologies 1: 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1353/cla.0.0000.

Geria, Sonner, Fanny Mafuta, and Gertrud Boden. 2025. Khwedam ǁacan o tham. Khwedam Learning Book. Oswin Köhler Archive and Bwabwata Khwe Community.

Gordon, Robert. J. 1992. The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. Westview Press.

Köhler, Oswin. 1989-1997. Die Welt der Kxoé-Buschleute. Eine Selbstdarstellung in ihrer eigenen Sprache. 3 vols. Dietrich Reimer.

Köhler, Oswin. 2018-2021. The World of the Khwe Bushmen in Southern Africa. A Self-Portrait in their own language. 4 vols. Edited by Gertrud Boden and Anne-Maria Fehn with assistance from Thaddeus Chedau. Dietrich Reimer.

Mountain Horse, Alvine, and Alison K. Brown. 2019. “Building Relations: Bringing Together Blackfoot Ways of Knowing and Museum Practice.” Presentation at Best Practices of Collaborating with Members of Source Communities in Museum and Archival Collections Conference, Goethe University Frankfurt, 7-9 October 2019.

Muntean, Reese, Kate Hennessy, Alissa Antle, Susan Rowley, Jordan Wilson, and Brendan Matkin. 2015. “Ɂelǝw’kw – Belongings: Tangible Interactions with Intangible Heritage.” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 7 (2): 59-69. https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v7i2.159.

OKW 325-1: Application for travel grant 1971. Oswin Köhler Archive, Goethe University Frankfurt. OKW 325: Reiseberichte (Expeditionen) 05 – 1971.

Onciul, Bryony. 2015. Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice. Decolonising Engagement. Routledge.

Scott, Mary Katherine. 2012. Engaging with Pasts in the Present: Curators, Communities, and Exhibition Practice. Museum Anthropology 35 (1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2012.01117.x

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession: 33-40.

Silvester, Jeremy, and Napandulwe Shiweda. 2020. “The Return of the Sacred Stones of the Ovambo Kingdoms: Restitution and the Revision of the Past.” Museum and Society 18 (1): 30-39. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v18i1.3236..

Turner, Hannah. 2020. Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. UPC Press.

Widlok, Thomas, Elena Kerdikoshvili, and Arden Thuis. Forthc. “How Things Connect People: Debating Access to Ethnographic Collections.” Kölner Arbeitspapiere zur Ethnologie.

[1] https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/454798691?language=en

[2] https://naturaljustice.org/publication/biocultural-community-protocols/; accessed 3.3.2025. Up to today (July 2025), the Khwe BCP has not yet been officially launched.

Gertrud Boden holds a PhD from the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Cologne. She wrote her thesis about social change among the Khwe in today’s Bwabwata National. After an absence period during which she worked on diverse subjects among other San communities in Southern Africa with only occasional visits to the Khwe, she started to work on the academic legacy of Oswin Köhler in 2015. Since then, she edited the up-to-then missing volumes of a vernacular encyclopaedia on Khwe culture, together with Anne-Maria Fehn and with assistance from native speaker Thaddeus Chedau, and engaged in different forms of collaborative research with Namibian Khwe.